In 2006, we published Shared-Equity Homeownership, a report by John E. Davis. In that seminal report, Davis argued that CLTs and LECs, along with long-term deed-restricted housing generated by inclusionary housing policies, constituted a “third-way” housing sector, somewhere between renting and traditional homeownership. The sector was marked by long-term affordability, a sharing of the responsibilities and benefits of ownership between household and community, and a need for long-term stewardship of land and homes.

Despite the stellar performance of community land trusts during the foreclosure crisis, for a long time, the conversation around these models has revolved around their small scale and the lack of familiarity with them.

But over the past several years, this has begun to change. In the face of accelerating gentrification in many markets, along with ongoing speculation and eviction in all markets, the idea of putting substantial numbers of homes outside of the reach of the speculative market has been gaining momentum across the country. There have been big wins for CLTs in New York City, new financing for land trust mortgages, ongoing momentum in converting land-lease mobile home parks to resident-controlled cooperatives, and the expanding of inclusionary housing policies to many new municipalities. The burgeoning housing justice movement is combining traditional organizing for renters’ rights (more on that in our next issue) with the goal of collective ownership and control. Large players, from Enterprise to Habitat to Citi Community Development, are throwing meaningful support behind the ideas of permanent affordability. In fact, Grounded Solutions Network has just announced a $1 million Citi-funded CLT accelerator fund.

In this issue we take a look at where models of permanent affordability and shared equity stand now, how they have fared over time, and how they could be expanded into new places (here and here)—even some places where existing community development organizations weren’t so eager to embrace them.

Holding some homes outside the whims of a market that sees them primarily as investment vehicles is making more and more sense to more and more people. But of course we are also operating within that market, which has led to a frustration over the years that for every new affordable unit we manage to build, we lose several units of existing affordable housing—whether to expiring affordability regulations, demolition by neglect, or price appreciation in changing neighborhoods. We explore a growing push to stem that tide with financing mechanisms that allow affordable housing nonprofits to compete on the open market to grab housing before it gets upgraded out of affordable range. For another approach to this, see the National Housing Trust’s HOPE initiative.

We also have some quick takes on “What Community Control of Land Means,”pulled from the diverse and inspiring array of perspectives and proposals readers sent in response to our call for essays on the topic. This isn’t a simple question—we urged writers to go beyond simple answers and talk about who “the community” is and what kinds of control they should exercise.

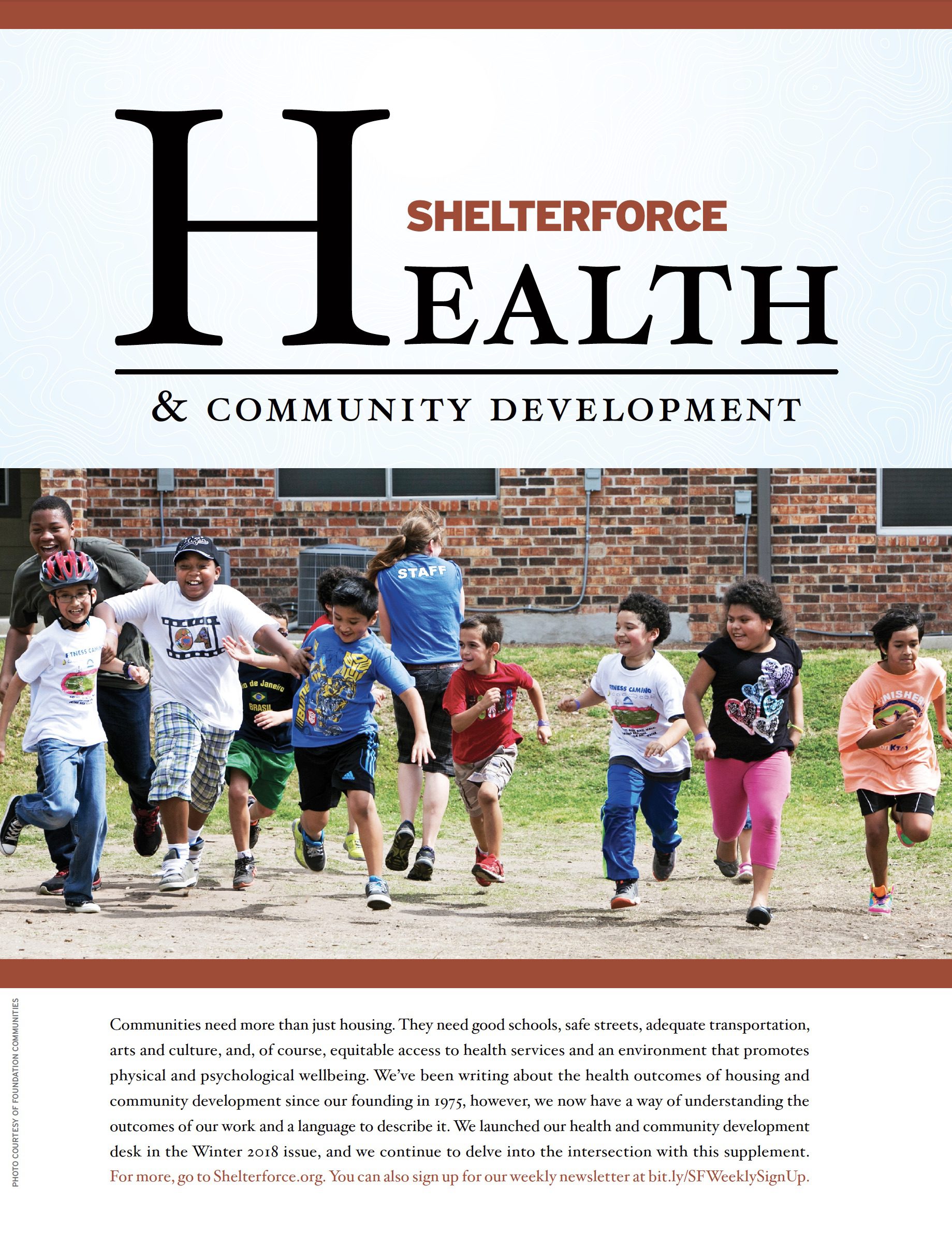

Finally, after officially launching our health and community development desk with our last issue, we’re pleased to continue our coverage with a pullout section in the middle of this issue. Do you have someone from the health care sector on your board? Have you considered what sorts of insights they might bring? Here are some ideas.

Also in that section, Ryan Petteway challenges our assumptions about place and health. Yes, place affects health, but, he argues, despite that great sound bite about ZIP codes and genetic codes, neither ZIP codes nor census tracts do a sufficient job of describing the geography of health factors people encounter in their daily lives. He describes another approach.

Comments