In 2014, United Workers joined with hundreds of community members who demanded quality education, good paying jobs, public services, safe neighborhoods, and permanently affordable housing in coordinated marches that convened at Baltimore’s City Hall. Photo courtesy of United Workers

On the morning of April 27, 2015, Freddie Gray was buried. By mid-afternoon, after two weeks of peaceful protests that began when Gray’s mysterious death in police custody became public, the police department’s silence became too much to bear. The rebellion began.

By the time the Maryland National Guard was summoned, 150 cars and 60 buildings were burned, 250 people were arrested, and almost 300 businesses were damaged.

After the smoke cleared, the national media descended onto the city, sifting through the embers for root causes. One image dominated most narratives: vacant houses—rows and blocks of them. Like most Rust Belt cities, Baltimore has its share of vacant properties. As many are linked row houses, there are city blocks that look war torn.

Oblivious to the war on Black and poor communities that has been waged for the last 100 years, the media’s analysis turned to a more familiar war—the war on poverty—and examined past efforts to transform Baltimore’s poor communities. The Washington Post looked at a mid-1990s effort to transform Gray’s neighborhood in Sandtown and asked, “Why Couldn’t $130 Million Transform One Of Baltimore’s Poorest Places?”

The cynicism surrounding past community development strategies was familiar to us at the Baltimore Housing Roundtable (BHR), but for other reasons. Our group of homeowners, renters, persons without housing, nonprofit developers, community associations, religious institutions, policy experts, lawyers, and university faculty had been meeting together monthly for 18 months at the behest of the United Workers (UW), an economic human rights group that organizes low-income communities. Having watched the federal government abdicate any responsibility to adequately fund deeply affordable housing, we were exasperated that city housing policy seemed focused only on “market- rate” developments and market-based strategies.

To us, vacant housing and homelessness in the same area was illogical, a demonstration that market forces alone could not meet human need. Why the deference to market-based solutions to community development and affordable housing?

Prior to the rebellion, we had worked to create and conduct a successful “Leadership School” where low-income community members met weekly for eight weeks to explore the city’s housing history with block-busting, redlining, restrictive covenants, urban renewal, homelessness, Hope VI, and the Rental Assistance Demonstration program. We had studied the public policies that assisted industrial job flight, retail flight to the suburban ring, and the creation of a publicly subsidized, permanent low-wage tourist and entertainment sector. We examined the roots of the homeless crisis in the late 1980s, and the foreclosure crisis of 2008 through 2011. And we looked at global forces and the changing nature of capitalism by discussing NPR’s “Giant Pool of Money,” an examination of the mortgage crisis and the financialization of housing.

Informed by this analysis of structural racism and structural inequality, leadership school students explored the values they preferred in housing and Baltimore’s economy: equity, universality, participation, transparency, and accountability. These became the BHR principles.

We found that community land trusts (CLTs) embodied these values. Community land ownership promised control, through resale formulas, over the speculative forces of the housing market; and racially diverse, community-elected, CLT boards offered neighborhoods an avenue of agency and real accountability. The creation of new community institutions in neighborhoods that had lost many offered the promise of social cohesion that was a key to sustainability.

The evidence relative to CLT performance was impressive. During the foreclosure crisis, CLT homes were relatively immune to delinquency and eviction. Equity gains for low-income, first-time buyers exceeded those of other homeownership programs. More importantly, most successful CLTs were the by-products of successful community organizing.

Yet CLTs rarely scaled up to become a significant part of the housing sector in any city. In Baltimore, we decided to think big from the start. We set a three-phase plan—education, demonstration, and then the final goal of scaled-up operation—with city public subsidies to make shared-equity housing a significant sector in the Baltimore housing market. Baltimore Housing Roundtable formed three operational arms—public policy, technical assistance, and community organizing—to forge a coherent vision and campaign.

UW organizers began introducing the idea of land ownership to community groups they were organizing, and the idea was favorably received. Policy wonks began planning a white paper report that would identify federal trends; the failure of 40 years of market-driven, trickle-down development; and the need for a new development paradigm. And lawyers and community development law school clinics provided guidance on CLT creation, ground leases, resale formulas, and more. A new CLT was created in Northeast Baltimore, a declining one in East Baltimore was resurrected, and four other neighborhoods were interested in creating CLT entities.

To us, the “failure” of past community development efforts didn’t warrant throwing the proverbial baby out with the bath water. All these efforts had produced the educational building blocks for a new approach: active and direct agency of neighborhoods through community land ownership.

CDC Opposition

Well before the rebellion, BHR members began rolling out our vision in one-on-one discussions with developers, community development leaders, foundations, and other opinion influencers. We met nothing but resistance.

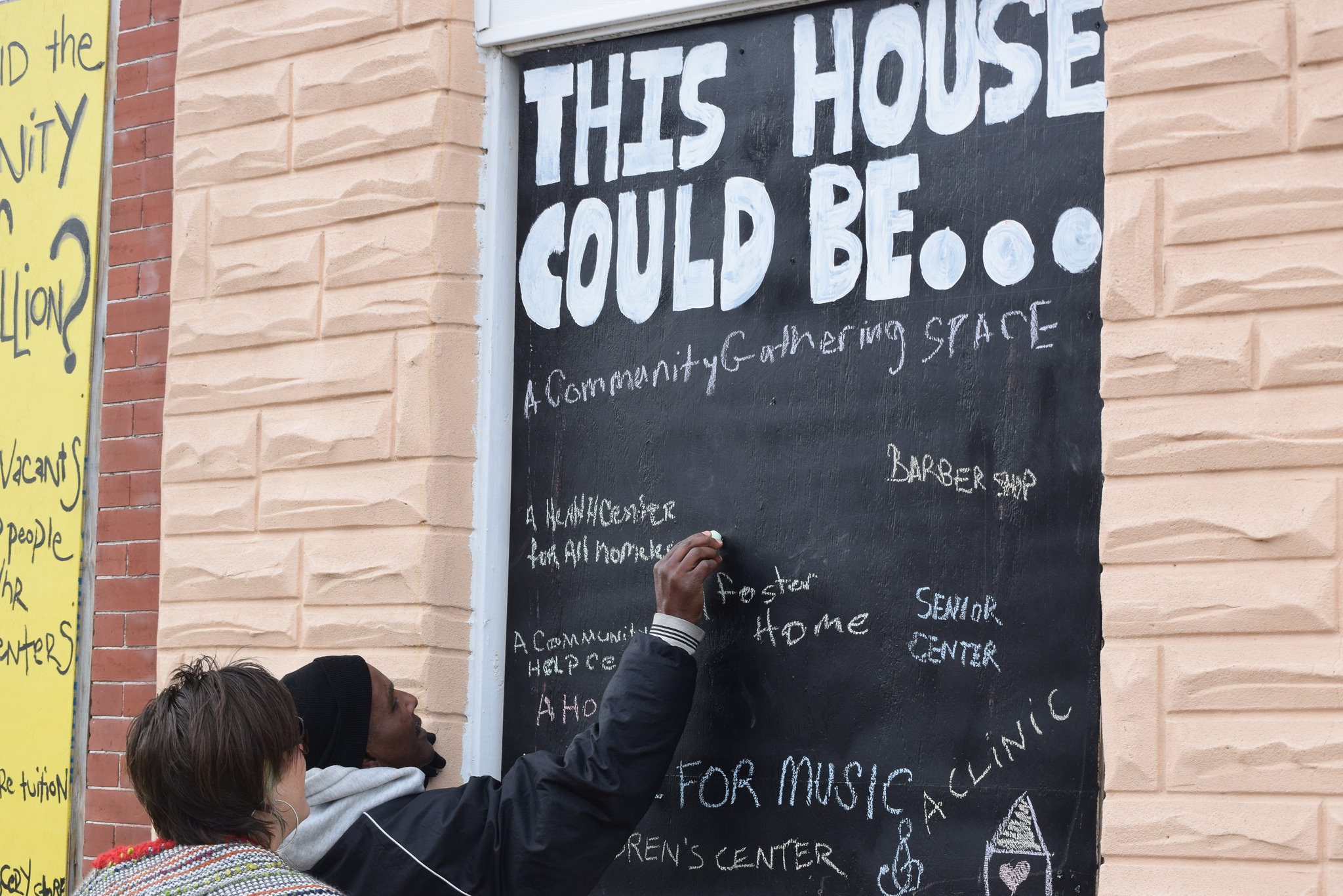

In 2016, community members transformed the plywood boards on three vacant houses in Baltimore by painting over them with colorful images of what neighbors would like to see in their community, including recreation centers, grocery stores, parks, green spaces, storefronts, and career centers. Photo courtesy of United Workers

Our first challenge came from legacy CDCs. When federal money was abundant, Baltimore was flush with CDCs. By 2015, though, only a few were left and the veterans had assembled into a few large partnerships, which were designed to provide cross-neighborhood support for organizing and development in particular geographic footprints, akin to catchment areas.

Most partnerships already familiar with the CLT concept saw it only as a tool to fight against gentrification. This was not Baltimore’s problem, we were told. It was just the opposite. Property values in many neighborhoods were declining, and legacy CDCs were about reversing that trend. “We could use a little gentrification in Baltimore,” we were told a number of times, and some CDCs weren’t afraid to admit that this was, in fact, their goal.

Baltimore was, in fact, gentrifying. A Governing report in February 2015 put Baltimore at No. 15 among 50 cities examined in the relative percentages of census tracts considered “gentrified.” Some neighborhoods were indeed “hot.” But most were not, as a city official noted when we cited the study to him. “Baltimore has plenty of room,” he said. In short, the city had plenty of neighborhoods where displaced households could relocate.

Whether he knew it or not, the official described the serial displacement that many of our members had been experiencing for years as poor participants in a speculative housing market.

At an early 2015 “Housing Speak Out” in East Baltimore, Shantress Wise took the microphone and announced, “In the last 20 years I had to move 16 times . . . the first time, a developer bought up our whole block, he started pushing us out of our homes and only gave us 60-day notice . . . He promised us that we would come back after rehab, but it was a broken promise. They doubled the rents and we never came back. On that block, there was a person who had been there since the 1960s, and they pushed her out as well. [Then] . . . I was working as a housekeeper, and lost two weeks of work for surgery and when I came back, I was no longer on the schedule. That was the first time I experienced homelessness.”

Beth Myers-Edwards, a lifetime renter, followed. “I’m 29 years old, a Baltimore native, and I’ve been renting my whole life. In those 29 years, I sat down the other day and counted, I’ve moved 21 times . . . So the dream of owning a home to me has only been about one thing—stability. Despite being the first person in [my] family to attend college, and working two jobs, I still don’t qualify for an FHA loan. So in a system that prioritizes profit over people, I’m not Beth. I’m a dollar sign walking down the street.”

The city’s rent court statistics buttressed their stories. Roughly 150,000 eviction cases are filed annually. When added to the foreclosures and the unhoused, we had almost one-third of the city’s population at risk of homelessness.

But the CDCs and many city officials saw this only through the silo of incomes. Baltimore was simply poor and had, in fact, too much low-income housing. “Baltimore doesn’t have a housing affordability problem, it has a poverty problem,” was a refrain we frequently heard.

Yet the jobs that had been created in the city’s pivot from industry to tourism and hospitality were without dignity or reward. In 2007, the National Economic & Social Rights Initiative and United Workers put together a report on Inner Harbor restaurant work. Interviews with 1,000 workers over a three-year period revealed low and unpaid wages, layoffs prior to scheduled pay raises, unaffordable health insurance, gender-based discrimination and sexual harassment, and work environments that were anti-family and anti-union.

Some city councilors, like Carl Stokes, fought to condition city subsidies on the creation of “good jobs,” but he was an outlier in a council whose majority was sold on neo-liberal development with no strings attached to public money.

Higher earnings would, of course, put upward pressures on rents. Without a dual strategy of raising incomes and the locking-in of affordable housing, the speculative housing market would undercut any income gains. As with gentrification, this seemed to be a problem most in the city would welcome.

UNITE HERE Local 7 was an exception. The union of hotel workers, a partner with the United Workers in prior fights over public subsidies to developers, recognized that raising wages alone risked higher housing costs that could force its members into outlying counties, diminishing the union’s local political leverage. Roxie Herbekian, local president, became a champion of CLTs and began pulling us in to campaign strategy sessions to discuss housing related “asks,” and to discuss CLT models that might serve union members.

But on the whole, we realized that there was a common interest that joined elected officials, developers, and homeowners into a formidable political bloc: rising property values. Property appreciation meant equity to homeowners, profit opportunities for developers, and revenue for a city government reliant on property taxes. As developers financed candidates for city elected office and homeowners voted more regularly than renters, property value appreciation was the de facto goal of the city’s development policy.

The Challenge of Concentrated Poverty

While the inevitable rising tide would indeed push low-income households and families of color out of Baltimore eventually, the political dynamics prevented it from being addressed. There was another formidable group that welcomed this mobility, albeit free from market coercion.

In 1995, the Baltimore chapter of the ACLU filed a public housing desegregation class-action lawsuit, Thompson v. HUD, which produced a consent-decree-governed housing mobility program.

Brandon McGoogan speaks to a crowd during the “Vacant House Art Takeover.” Photo courtesy of United Workers

The lawsuit, filed strategically on the eve of Baltimore’s planned HOPE VI housing demolitions, initially produced a partial consent decree whereby more than 3,000 public housing units scheduled for demolition were to be replaced with new housing opportunities in a tri-partite manner: one-third was new mixed income, replacement public housing; and two-thirds were to be either newly developed or acquired hard units or Housing Choice Voucher program-leased units in white, low-poverty areas. Specifically, vouchers under the Thompson decree could be used only in census tracts where poverty rates were 10 percent or lower, Black household residency was 30 percent or less, and the substandard housing rate was 5 percent or less.

The decree effectively combined the positive aspects of HUD’s Moving to Opportunity and Regional Opportunity Counseling Program into a more ambitious and better-resourced mobility program that was administered separate from the local housing authority and accountable to a court. In short, the Thompson decree, like the 1976 Chicago court ordered remedy in Hills v. Gautreaux, was setting the gold standard for housing mobility programs.

The lawsuit alleged racial discrimination by HUD and the Housing Authority of Baltimore City. While this discrimination involved persons who were poor, the term “concentrated poverty” emerged in common conversation as the demon Baltimore needed to exorcise.

Repeatedly we heard from public officials, foundations, and developers that BHR’s community-driven development goal, where community land ownership would develop and steward affordable housing, was misguided because it would continue to produce “concentrated poverty.”

At BHR, we saw mobility as one tool among many to fight individual and community poverty. Our organizing in “blighted neighborhoods” had introduced us to a number of committed community leaders, and had fueled small areas of community synergy that, in our opinion, lacked only resources for success. To us, no neighborhood should be abandoned regardless of whether and how people were offered subsidies to move. We couldn’t address the needs of just some people; we had to address the needs of all.

Avoiding investment in communities where poverty was “concentrated” seemed to unintentionally but effectively perpetuate institutional racism, internalized racism, implicit bias, and a new type of redlining. Baltimore City’s 2014 Housing Market Typology map, which color-coded neighborhoods as “stressed” to “choice” based on vacant housing rates, median sales price, and owner occupancy of housing, seemed eerily similar to the 1937 redlining maps, absent explicit factors of race, ethnicity, and religion.

The tipping point came when The Washington Post planned a story about our efforts to transform vacant homes into housing for the homeless. Mobility advocates criticized our ideas and perspective to the Post reporter, and it was only our last-minute intervention with the reporter that saved us from appearing as hopeless and misguided ideologues.

The tensions apparent in the article were too much for a local foundation that had supported both mobility and place-based efforts. It asked housing advocates, lawyers, and BHR members to gather at its office, and discuss different strategies in the hope for some harmony. The meeting ended tensely, as the Post article was raised and discussed.

The foundation mediated effectively and we agreed to meet again.

During subsequent meetings, familiarity and respect began to replace distance and distrust. Members of the group less committed to a particular strategy were able to move us to the realization that in-fighting and disunity was shortsighted, given the political difficulty of funding any low-income housing assistance.

Eventually, we all committed to raising those resources through the creation of a Baltimore City Affordable Housing Trust Fund, which would fund a variety of strategies. The trust fund was later realized through a City Charter Ballot Initiative spearheaded by the United Workers, and supported by the housing advocates group hosted by the local foundation.

Changed Landscape

As we at BHR watched Baltimore burn on the day of Freddie Gray’s funeral, we had no idea that our political landscape was undergoing an earthquake.

At first, it was invisible. We joined with UNITE HERE and other labor leaders to release an equitable development policy platform that also included a human rights charter amendment. While it got little traction, it became the frame for Community + Land + Trust: Policy Tools for Development Without Displacement, a broader report released by the BHR in 2016.

By then, we recognized change was afoot. Not only did the report release draw a big crowd, the city’s Democratic primary was less than three months away and candidates were asking for copies of our study. Place-based strategies seemed to have new support and opportunity.

Children work out at the United Workers’ 3rd Annual Westside Bar B-Q in Baltimore in 2015. Photo courtesy of United Workers

Our report advanced community-driven development, featuring a call for a “20/20 vision,” $20 million annually in municipal bonds for projects to advance CLTs and permanently affordable housing, and another $20 million annually in bonds for vacant housing deconstruction or demolition, community greening and community agriculture, and prioritizing the hiring of persons with a record of law enforcement involvement. It also called for a city Housing Trust Fund, targeted to persons at 30 percent AMI or lower.

Our labor-community ally, UNITE HERE, echoed the call as they moved into electoral politics, pushing city council and mayoral candidates to embrace “Fair Development” in spring 2016. Two council incumbents were targeted and defeated in the primary election, and the eventual nominee for mayor, Catherine Pugh, endorsed 20/20, holding aloft BHR’s report at a community development forum.

In the pre-final election period, UNITE HERE joined again with the UW and BHR to canvass houses with mortgages that had been purchased by the equity giant OakTree Capital Management. OakTree pursued its own form of exploitation—re-financing on predatory terms with employed homeowners, foreclosing on the disabled and destitute, and holding foreclosed-upon vacant housing until property values rose. The contrast between this global speculative strategy and community-driven development was brought to the attention of the city council.

In November 2016, voters approved a City Housing Trust Fund and BHR looked to 2018, when the mayor would produce a budget formed by her administration.

At the time of this writing, the mayor has backed off from her campaign commitment and post-election endorsement of 20/20. A likely mobilization of city council allies, 10 of 14 of whom have endorsed the vision, will determine her accountability. The final budget will be passed in June. Regardless, we are now in a position to advance a legislative proposal targeting new tax revenue to the Housing Trust Fund and to mobilize another charter ballot initiative, if necessary.

In the meantime, the new city administration has tentatively embraced a pilot project to test the CLT concept with multiple, interconnected CLTs. BHR has worked with the two established CLTs and the four CLTs-to-be to coalesce into a network, Share Baltimore Inc., which hopes to maintain a regular accountability and support space for all members.

Mattering in Baltimore

While the CLT movement in Baltimore is far from piercing the formidable political alliance that drives local public policy toward increased property values, we have, in five years, put community ownership of land into the policy mix, prompted a city pilot project, and been able to establish a foothold for place-based strategies, post rebellion. In short, Black neighborhoods do matter now in Baltimore, and we hope community-driven development is recognized as different from the neo-liberal models that have been tried before.

Where that goes remains to be seen, but if the Curtis Bay community in Baltimore is any indication, it will only grow in positive ways. There, UW community organizing in a low-income neighborhood saddled with years of industrial development and community health issues focused on a proposal to place a super-incinerator within a mile of a local high school. As high school youth researched the siting process, they used the UW Fair Development principles to critique it and envision alternatives. They also explored the history of their own community, discovering that it had been annexed by the city to operate as an industrial zone. The youth spearheaded a successful anti-incinerator campaign, and began advancing community control of land as a solution to years of environmental racism. The CLT that is being created will bring together local high school administrators, students, homeless service providers, urban agriculturalists, environmentalists, and community activists—all initially linked by the incinerator campaign.

Unlike in the past, Curtis Bay residents will not be content to be interested bystanders or consultants to community development, but actual agents of it. Control of community land to them means the control of housing speculation, siting of pollutants, and preservation of neighborhood businesses. It also is the means to develop permanently affordable housing, solar energy, fresh food, and community-oriented enterprises.

Curtis Bay and the Baltimore Housing Roundtable began building a community base and community-driven development frame well before the Baltimore rebellion. While we couldn’t have anticipated the uprising or the changed dynamics it would produce, we know that we wouldn’t be where we are now, absent the organizing that allowed us to move into the policy vacuum it exposed.

Comments