This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Landlord-tenant relationships are inherently imbalanced: In a legal system that privileges property owners, landlords hold most of the power. They control access to housing through the ability to set rents and to evict, sometimes with no justification. They control whether their tenants have a safe, sanitary place to live by fulfilling or ignoring maintenance and repair needs. The situation is so lopsided that tenants often fear making requests or complaints or asserting the rights they do have.

Housing justice advocates have long been pushing for a national tenants’ bill of rights that would shift the choice of whether a tenant can stay in their home away from landlords and toward tenants, says Tara Raghuveer, the Homes Guarantee campaign director at People’s Action.

“Our ‘North Star’ is a homes guarantee, which is a full transformation of our housing system from one where housing is delivered as a commodity to one where housing is guaranteed as a public good,” she says. “We’re not under any illusions that that’s winnable in the short term. There’s got to be some steppingstones and milestones. We see a tenants bill of rights as a milestone victory that will take us toward a homes guarantee. Tenant protections are a necessary intervention in the distorted power dynamic between landlords and tenants.”

Getting a tenants bill of rights passed in Congress also isn’t likely at the moment, says Raghuveer, though People’s Action is pressuring the administration to do some smaller things to protect tenants. However, housing activists across the country are actively organizing to get tenant protections enacted locally.

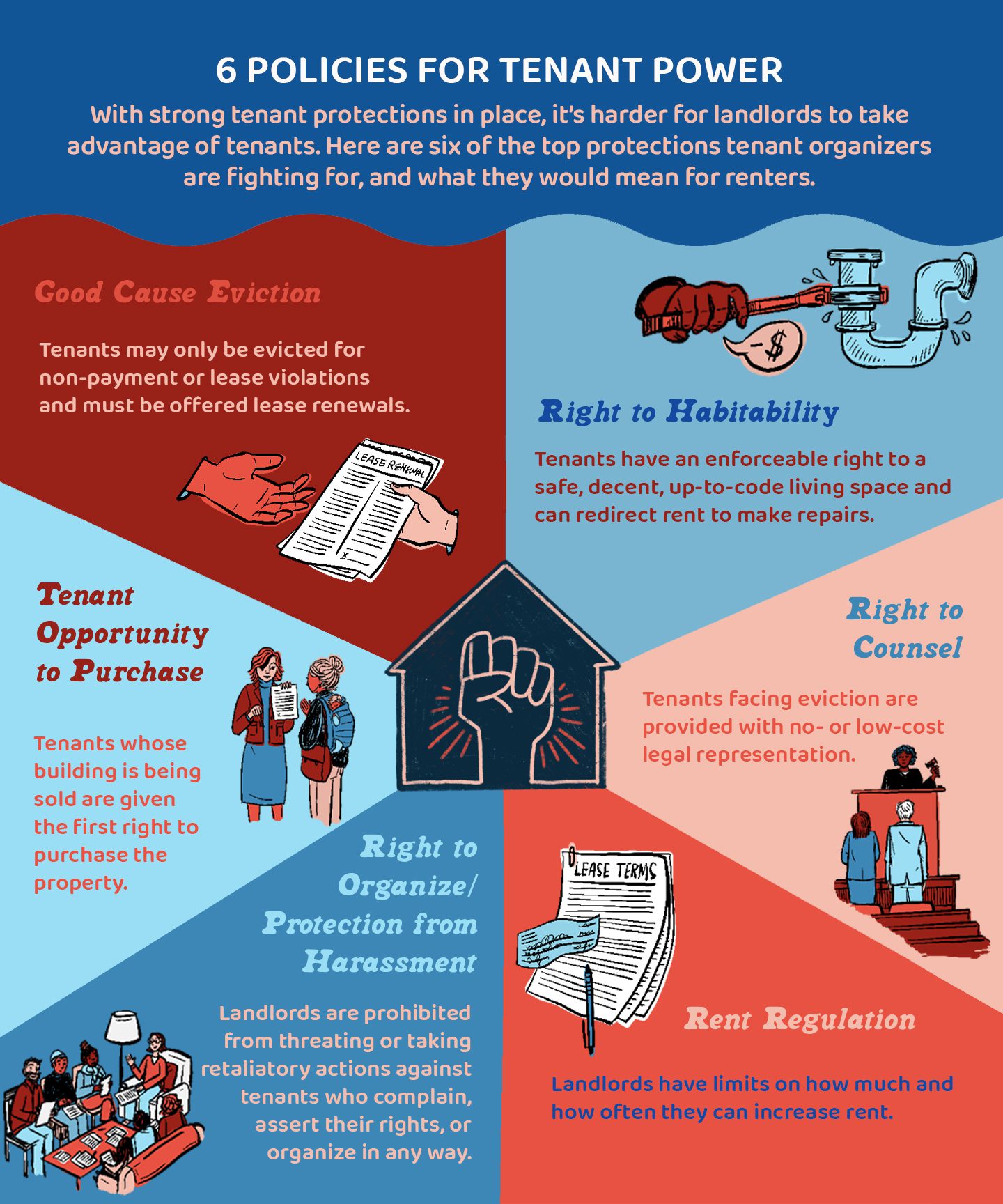

So what exactly do “tenant protections” or “tenant rights” entail?

Six tenant protections appear on most organizers’ wish lists: just cause eviction, right to habitability, right to counsel, rent regulation, right to organize/protection from harassment, and tenant opportunity to purchase.

Good Cause Eviction

In most places, landlords don’t have to allow current tenants to renew their leases when their original lease expires. Good cause eviction, also known as just cause eviction, changes that by prohibiting landlords from terminating tenancy for renters who are in good standing—meaning they don’t owe the landlord money and have complied with the terms of their lease.

Many good cause eviction laws also contain provisions that prohibit landlords from increasing rents by more than a certain amount when leases renew. While not a formal eviction, an exorbitant rent hike often serves as a de facto eviction because existing tenants who can’t afford the increased rent are forced to move.

There is no just cause eviction law at the federal level, although it would be within the power of Congress to enact one. Some states—including California, New Jersey, and Oregon—already have good cause eviction and rent increase protection laws on the books. Oregon’s law, for example, took effect in 2019 and protects renters from eviction for no reason as long as they’ve been in their home for more than a year. It also caps rent increases at 7 percent more than inflation. (In 2023 the recent soaring inflation will still mean landlords can legally jack up rents by 14.6 percent. But that’s still better than 30 to 100 percent rent increases, which have been frequently recorded in recent years.)

[RELATED ARTICLE: Eviction Filings Hurt Tenants, Even If They Win]

In other states, tenant advocates are fighting to get such a law passed. New York tried and failed in the last legislative session to pass a law that would have required a good cause for eviction and limited annual rent increases to either 3 percent or 1.5 times the annual percentage change in the Consumer Price Index, whichever was greater.

Some core components of good cause legislation include defining grounds for landlords to legally evict tenants; limiting rent increases, or at minimum requiring relocation assistance in cases of rent hikes greater than a certain threshold; boosting requirements for written notice of lease terminations, court dates, and lease changes; and requiring that landlords give tenants the right to cure lease violations. Right to cure means if a tenant owes money, paying it would end an eviction proceeding, or if they have a pet in violation of a no-pet policy, getting rid of it would similarly forestall an eviction on those grounds.

Right to Habitability

All states except Arkansas recognize an implied warranty of habitability—which means leased units must include safe and clean basic structural elements (floors, walls, roofs, etc.), working utilities (electrical, plumbing, heat, etc.), and be free of pests and environmental hazards. But these warranties aren’t always upheld; some landlords and property management companies regularly ignore requests for maintenance and/or don’t adequately fix the problems.

Tenants whose landlords fail to maintain functional heating units, water service, or other material features, thereby rendering the home unlivable, have a few options for recourse. For starters, they can report the landlord to a local housing authority or building code enforcement agency. By taking this route, though, tenants put themselves at risk of having their home condemned. While this action is ostensibly done to protect the tenant, it could force the tenant to seek alternate, possibly more expensive, housing, or lead to homelessness. This allows landlords to ignore maintenance requests, especially those made by low-income tenants, tenants with prior evictions, or other tenants whose life circumstances make it hard to find landlords who will rent to them.

Many jurisdictions allow tenants to withhold rent or place rent in an escrow account in cases where maintenance issues render their home uninhabitable. But the procedure for withholding rent can be onerous, requiring tenants to file a court case. Additionally, they must still pay rent, albeit to the court, which means in cases where the unit can’t be lived in tenants end up paying their original rent and the cost for an alternate living situation.

Repair-and-deduct laws put somewhat more power in tenants’ hands: If a landlord doesn’t make a needed repair within a certain amount of time, the tenant can have the issue fixed and withhold the cost of repair from their regular rent payment. This remedy does require tenants to pay up front for often costly repairs. Additionally, states that do have statutes legalizing repair-and-deduct remedies often limit the amount tenants can spend/deduct or require tenants to sue for reimbursement in small claims court. These types of laws also often require the tenant to provide written notice to the landlord, sometimes putting them at risk of harassment or even eviction before they even get to exercise their rights.

To realize a right to habitability, tenant advocates recommend combining repair-and-deduct remedies with protections against retaliation for using it, and mandating relocation assistance in the event a landlord fails to adequately address habitability issues.

Right to Counsel

Approximately 97 percent of tenants facing eviction lack legal representation, according to the most recent data from the National Coalition for a Civil Right to Counsel. That’s largely because evictions are heard in civil court and defendants in civil court cases are generally not provided with free access to an attorney (as low-income defendants in criminal cases are). The result is that most tenants lose their eviction cases. Many are forced to accept deals with their landlords that they can’t afford or even self-evict to avoid going to court altogether.

Providing renters with a legal right to counsel—meaning that either all tenants or those who meet financial eligibility requirements would be appointed an attorney at no cost to them—drastically reduces eviction rates. A 2018 study showed that fully represented tenants won or settled their eviction cases 96 percent of the time, 80 percent of represented tenants left court without an eviction on their legal record, and tenants with legal representation are four times less likely to need homeless shelter services. Right to counsel laws encourage landlords to consider eviction diversion options and frequently give tenants better access to rental assistance and fair repayment plans.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Right to Counsel Movement Gains Traction]

In 2017, New York City enacted the first right to counsel ordinance for housing court. It provides tenants whose earnings are less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level with access to legal counsel. In the last quarter of 2021, 74 percent of tenants were represented by an attorney in NYC housing court, and 84 percent of tenants who had legal representation were able to remain in their homes.

As of mid-2022, 15 cities and 3 states had passed similar laws. Of those, just five cities provide free legal representation to anyone facing eviction. The others limit free counsel to “qualified” tenants, meaning the right is limited in some way. One common way of limiting access to legal representation is via “means testing,” which requires tenants facing eviction to prove low-income status before being provided with an attorney. While meant to discourage well-off renters from “stealing” benefits, decades of research has shown that means testing for government programs creates stigma that discourages participation by people who truly need services. Not only that, but data shows that an overwhelming number of renters who receive an eviction court summons are from low- and moderate-income households. Therefore, most tenant advocates are pushing for laws that provide counsel for anyone facing eviction, regardless of income or their ability to prove need.

Rent Regulation

In many places, rents have been high for years, but since the pandemic, rents across the nation have increased at the fastest pace in decades. Nationally, rents jumped by 11.3 percent in 2021, and 2022 hasn’t brought any relief. In some particularly hot markets, such as Miami, average rents skyrocketed by more than 50 percent—with individual homes’ rent going much higher. And in several cities where rents had been relatively affordable—such as Fresno, California; Columbus, Ohio; and Tulsa, Oklahoma—increases topped 30 percent year over year.

In October, more than a dozen tenant-led organizations participated in a National Mega Canvass across the country. Groups like the Louisville Tenants Union, pictured above, spoke with tenants to learn more about the effects of rent hikes in their households. Photo courtesy of People’s Action

Price-gouging increases like these are why rent regulation has historically been and will remain a core policy demand from housing justice activists. Today, five states—California, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Oregon—and Washington, D.C., have some form of rent regulation in place. St. Paul, Minnesota, and Portland, Maine, have also enacted it, and several California cities have stricter versions than the state law. Nine states allow it but have no jurisdictions that have implemented it, while 37 states prevent municipalities from enacting rent regulation altogether.

Rent regulation can take many different forms. Anti-rent-gouging laws rule out particularly large increases, while rent stabilization typically limits increases to something much closer to changes in costs. Allowable increases might be a fixed percent, pegged to inflation and/or changes to the Consumer Price Index (or other index), or determined yearly by a review board, as is done in New York City. In most places that have enacted forms of rent control and rent regulation, the laws don’t apply to new construction, allow for larger rent increases (or leaving regulation) when an apartment is vacated, and provide for increases to compensate owners for capital improvements—but all those factors vary place to place. Some rent control laws, such as California’s, exempt single-family, owner-occupied homes and duplexes in which the owner occupies one of the units.

People’s Action is advocating for federal rent control that would set the annual allowable rent hike at 1.5 percent of the Consumer Price Index, or 3 percent of the previous rent amount, whichever is less. Last month a group of housing justice advocates, including the Homes Guarantee coalition, called on President Joe Biden to issue an executive order that would prohibit owners of rental units with federally backed loans from increasing rent by more than that.

Right to Organize/Protection from Harassment

Tenants organize and form unions to rebalance power between tenants and landlords. Collective action has a long history of generating pressure for change and influencing people in power positions. Tenants’ unions have existed for more than a century—in fact, Shelterforce got its start in 1975 as a way for tenant organizers and legal aid attorneys in New Jersey to connect with each other across the nation.

Tenants’ unions take on roles such as negotiating dispute resolutions, facilitating code enforcement and inspections, providing legal resources to tenants, documenting and reporting landlord abuses, coalescing in numbers to reduce the chances landlord intimidation will scare tenants into silence, and, when necessary, staging rent strikes.

Tenants who assert their rights or organize often face retaliation from their landlords in the form of verbal abuse, rent increases, no-cause eviction notices, or other actions that can be stressful and/or dangerous. Landlords who feel their power is being threatened are especially prone to harass tenants, says Shanti Singh, communications and legislation coordinator with California-based Tenants Together.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Renters Rise Again]

“It’s only escalated during COVID. As more tenants are organizing because of the conditions they’re in, they’re facing harassment, retaliation, and eviction for going to tenant association or tenant union meetings,” Singh says. “So something that was a priority for Tenants Together before COVID and remains a priority is the right to organize.”

Housing justice advocates want legal protections from landlord interference or harassment for tenants who complain, assert their rights, or organize. For example, under California Civil Code, tenants who are illegally locked out of their units can sue their landlord for as much as $100 per day. Additionally, California landlords who illegally retain tenant property or remove doors or windows as a form of harassment can be charged with a misdemeanor. (However such anti-harassment laws are only as good as their enforcement, or lack thereof.)

San Francisco recently passed an ordinance that specifically protects organizing activity within rental properties and the formation of tenant unions, much the way national labor law oversees the formation of labor unions. The law requires landlords to bargain with tenants who organize, “confer in good faith” with tenant associations, and attend at least four tenant meetings per year.

Tenant Opportunity to Purchase

Tenant opportunity to purchase policies, also called right of first refusal, allow low- and moderate-income tenants at risk of displacement due to the pending sale of their building to have a chance to purchase their units. Tenant opportunity to purchase acts (TOPAs) provide an opportunity to remove apartments from the open market, keep them out of speculators’ crosshairs, and preserve existing affordable housing. Though the process can differ among jurisdictions where it exists, generally property owners who want to sell must notify existing tenants, then must allow a specific amount of time for tenants to respond, provide a reasonable offer, and secure financing. Tenants can and often do assign their purchasing rights to a nonprofit housing organization they are partnering with to accomplish the purchase.

Washington, D.C., lawmakers enacted a TOPA more than 40 years ago. At the time, multifamily buildings, condominiums, co-ops, and single-family homes were subject to the law. In 2018, the D.C. council passed a law that removed single-family homes—including condos, co-ops, and accessory dwelling units—from the original legislation, leaving only properties with two or more units.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Giving Tenants the First Opportunity to Purchase Their Homes]

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors recently enacted a Community Opportunity to Purchase Act (COPA), which requires all owners of buildings with three or more units to notify qualified nonprofit organizations before listing the property, giving them the right of first offer and refusal. Tenants whose building is going to market can approach the city’s qualified nonprofits to suggest their building be purchased. The San Francisco model does not increase tenant decision-making power, but should still reduce displacement by putting qualified nonprofits in line before speculators.

PolicyLink has mapped where TOPA/COPA is in effect or is actively being fought for.

More Protections

While these are some of the core asks, this list isn’t exhaustive. Tenants’ rights groups nationwide are also pushing for a host of other policies. Some involve access to housing, like preventing consideration of criminal and/or past eviction history, sealing eviction records, or instituting source-of-income protections, which would prohibit landlords from refusing to rent to Section 8 voucher-holders or applicants with other nontraditional sources of income. Other policies include placing limits on fees, “clean hands eviction” laws that prevent landlords from evicting if they have open code violations, and providing relocation assistance during housing disruptions.

The Homes Guarantee campaign, which is pushing Congress to take up a national tenant bill of rights, is currently soliciting input from the public on “what rights are most critical for safe, sustainable, and permanently affordable housing.” In the meantime, the organizing continues.

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this story had outdated information about the percentage of tenants who lack legal representation and misidentified the number of states/cities that have passed right to counsel laws. It has been corrected.

|

|

I have been looking for accommodation for 3 months in London and it has been one of the most soul destroying experiences of my life. There is so much prejudice and discrimination against people not working and ageism. Landlords seem to be able to get away with almost anything from shoddy conditions and no rules of fair business practice. Some try to be trying to hide from any officialdom but it just means that rogue landlords can get away with almost anything. I have rented private accommodation for about 30 years and it is the worst shambles I have ever seen and I fear that myself and others will end up homeless as a result. Everything seems to be about preventing tenants from having any rights, especially with tiers of subletting, no fault repossessions. It feels so unsafe when looking for accommodation. Landlords may worry about problematic tenant .However, as a tenant it is also extremely difficult to know if landlords can be trusted to offer any professional standards of practice or trustworthiness, especially in the time and present market economy, in which so many people are seeking accommodation.

We all owe a debt of gratitude to Ms. King for concisely listing the most salient rights that tenants need to protect their existing tenancies. To those listed I would add several footnotes: a) As per court rules in NYC. landlords, to evict a tenant, cannot sue for more than 2 months due and owing. This prevents back due rents for tenants from piling up thereby making it impossible for tenants to become current, b) establishing percentages for the loss of certain services such a lack of heat and hot water. In New York, the Dept. Of Housing and Community Renewal has set percentages for the loss of such services so that when tenants are taken to court they may more directly assert the abatements they are entitled to, and c) to inform tenants that just because the building they live in is the subject of a mortgage foreclosure against their landlord, this does not mean that the tenants must move out.

This may sound extreme, but I think landlordism should be abolished as an anachronism