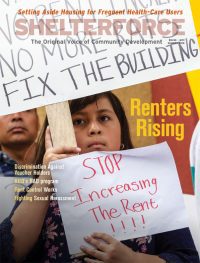

Mariachis, tenants, and Los Angeles Tenants Union organizers gather at Mariachi Plaza to raise awareness of their ongoing rent strike, demanding that their landlord negotiate. After more than a year, their strike proved successful and they won a collective bargaining agreement. Photo by Timo Saarelma

It’s the same story in city after city.

Unsafe and unhealthy living conditions; exorbitant rent increases; buildingwide evictions; and unresponsive landlords. It’s no surprise that the fight for tenant rights and protections is reaching a tipping point.

A decade after the housing crisis, there are now more renters in the U.S. than at any point in the last 50 years, according to the Pew Research Center. The demand in rental housing has led to substantially higher rents, which have become increasingly difficult to pay with wages remaining relatively flat. As if that weren’t enough to deal with, more and more renters are experiencing eviction. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Matthew Desmond, who penned the groundbreaking book Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, estimates that every minute, there are four evictions in the U.S.

Across the nation, groups are organizing to combat these issues by passing city- and statewide tenant protection laws. For instance, there is an effort to bring back rent control in California by repealing the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act. And there have been big wins, like the right-to-counsel movements in New York and San Francisco, where low-income tenants are provided with a lawyer in eviction court.

But in recent years, there’s also been a surge of smaller, yet equally important battles occurring in cities as tenants have taken their grievances directly to the source: absentee landlords. The resurgence of rent strikes, where tenants withhold some or all of their rent until their conditions are met, and face-to-face negotiations with landlords have led to victories for tenant associations, wins that include affordable multiyear leases, building repairs, and most importantly, the right to remain in their homes.

A “Green and Greed” Issue

An owner who treats one tenant unfairly is likely to treat all their tenants the same way, says Ronel Remy, an organizer with City Life/Vida Urbana (CLVU) in Boston. And the more tenants affected, the more people who can join an uprising.

Remy provides organizing support for a tenant association of residents who live in multiple buildings in Hyde Park, a neighborhood in the southernmost part of Boston. The buildings are owned by Advanced Property Management (APM), which has more than 300 units in its rental portfolio. For seven years, association members have fought back against exorbitant rent surges by staging a partial rent strike, refusing to pay the increases while their living conditions remain unchanged.

In Boston, a resident marches against a building eviction in 2017. Photo courtesy of City Life/Vida Urbana

Tenants have raised concerns to management about issues such as rodent infestation and mold growth, which can lead to asthma and other respiratory illnesses; and broken doors that allow nonresidents to enter buildings to use illegal drugs. The complaints have gone unaddressed by APM for years, says Remy. One resident, who has lived in the same apartment for 30 years, faces an $800-a-month rent increase, he says. The resident has been forced to live for years with a 25-year-old carpet that exacerbates his asthma despite his requests to have the health hazard removed.

“It’s not safe,” says Remy, who has regularly met with Hyde Park residents for a year and a half. “When I came on board I was frustrated to see [that] we couldn’t get [the owner] to move on anything, to change anything, or fix things in the apartments. We offered to negotiate and he would not budge.”

Though the owner has evicted residents who haven’t paid their full rents, there has been some positive movement recently. APM’s owner has finally agreed to meet with the tenants association to negotiate. Remy attributes this change to two factors: First, in November 2017, the residents organized and went to the owner’s personal community in Back Bay, an affluent neighborhood in Boston. “After we did that, he was a little more flexible and agreed we should meet. When [Back Bay residents] see you making a lot of noise and you’re bringing panels . . . chanting in the streets and walking through their neighborhood on a Saturday morning, they are upset and they don’t want a repeat of that.”

The city also intervened and told APM’s owner that he should negotiate with the tenants, says Remy. The sides have met, but each time the association believes they have reached a deal, the owner reneges before an official agreement can be signed. For instance, the group agreed that all association members would pay a $200 increase in order to get repairs done to their apartments. But shortly after the decision, APM said it would only repair 3 of 29 units the group submitted for repair, Remy says.

Both sides are now reviewing a lease that shows some potential, says Remy, but it also includes many clauses for eviction.

“It’s a green and greed issue,” he says. “They just care about how much money they can make right now.”

The situation throughout the neighborhood of East Boston is similar to that facing APM tenants at Hyde Park. It’s become the norm for tenants to receive rent hikes of 33 to 66 percent, says Helen Matthews, communications coordinator for CLVU. Two other common types of displacement tenants in the city face are no-fault evictions, where a tenant who doesn’t have a lease is evicted through no fault of their own, and buildingwide clear-outs, where every tenant in a building receives a no-fault eviction notice at the same time.

In the past five years, CLVU has supported tenants fighting in about 75 buildingwide clear-outs, and more than 20 of those renter households have successfully negotiated new leases after facing displacement. Most are two- and three-year leases, says Matthews.

“I think that’s where the tenant union strategy is so important. When a whole building is getting cleared out, that’s an opportunity for people to really exercise their collective power,” says Matthews.

But there are certainly roadblocks too. Landlords try to divide associations by offering some families deals that would be hard to refuse, especially when a fight has been going on for months, or even years. “It can be difficult for people to want to stay in the struggle,” says Matthews.

Negotiating a Long-Term Affordability Agreement

Nashville has had its fair share of challenges. Earlier this year, a tenants association at Union on Thompson Apartments dispersed after members were threatened with calls to ICE, says Kennetha Patterson, a tenant leader and organizer with Homes for All Nashville.

It was the second of three tenant associations in the city to disband. Now, only one remains: the Park at Hillside Tenants Association. The group formed after their 290-unit complex, Park at Hillside, changed ownership in 2016.

Kennetha Patterson of Homes for All in Nashville during Renter’s Week of Action, an annual event that aims to show landlords, developers, and city officials that the renter movement is rising. Photo courtesy of Homes for All

In Nashville, it’s become commonplace for developers to purchase buildings, remodel units, and increase monthly rents to market rates, leaving a wake of tenant displacement behind them. In the last several years, rent costs in the city have increased by 70 percent, says Patterson, while wages have risen by only 14 percent on average. Renters regularly struggle to find affordable and safe places to live, and many, including Patterson, have left the city altogether. “Teachers aren’t even able to afford to live here,” she says, adding that city officials don’t seem to understand there’s a dire need for affordable housing. They fixate on bringing a major-league soccer stadium to the city instead of focusing on the issues affecting its citizenry, she says.

Knowing this, residents at Park at Hillside united to ensure the affordability of apartments at the complex, as well as much-needed building and apartment repairs.

Josiah Goins, a member of the association, said the complex’s maintenance crew has regularly ignored safety concerns, like mold, and other apartment repairs. When a maintenance crewmember does follow up with a resident’s request for repair, the issue is often not addressed properly. For instance, Goins says tenants have complained that black mold was painted over instead of being removed. He’s even seen a ceiling caving inside one resident’s apartment. “Their reply is ‘[The owners] don’t pay us enough,’” Goins says.

The association sent a letter to the building’s new owners, Elmington Capital Group (ECG), with a request to discuss several proposals, including keeping residents in their homes, obtaining an affordable lease agreement, and addressing maintenance issues. To their surprise, ECG representatives agreed to meet. Over the course of a year and a half, both sides met about 10 times to discuss tenant concerns and the complex’s future, Patterson says.

Perhaps one factor that contributed to the company agreeing to meet with tenants was its plan to redevelop the area. ECG planned to build a 1,200-unit, mixed-used complex on the property, which spans about 24 acres. But before it could move forward with those plans, the proposal required approval from the Metro Planning Commission.

Because ECG wanted Park at Hillside tenants to support the project, Patterson says the association had the leverage it needed to successfully negotiate a long-term affordability agreement. Now, low-income residents who earn between 40 and 60 percent of the area median income can afford to live in 290 of the complex’s units.

“It was unprecedented,” says Patterson, who explained that monthly rents would remain affordable in perpetuity, even if the complex changes hands. That’s because the affordability restrictions were written into the zoning plans for the land, she says.

“This would not have happened if the tenants did not unionize. They just would have been displaced.”

Two other factors that contributed to the win: the tenants had the support of residential homeowners in the immediate area who didn’t want their neighborhood “to look like the rest of gentrified Nashville,” and there was one councilmember who wanted to “look good in the spotlight” before his bid for re-election, says Patterson.

In May, the city commission approved ECG’s redevelopment plan. The remaining units in the company’s plans will be used for commercial and high-end homes, says Patterson.

The company plans to rebuild the complex in phases, and Park at Hillside residents will be moved into new housing before their current building is knocked down.

Despite the win, Patterson says the fight isn’t over. The project isn’t expected to begin until next year, and in the meantime, “we are still battling management to fix things.”

The association isn’t sure what its next move should be. Members are aware of tenant groups that have participated in rent strikes, b ut the Park at Hillside Tenants Association is still weighing its options for future actions. The one thing they do know, says Goins, is that they want their win to be an example for preserving existing affordable housing in Nashville.

Rent Strikes: The Largest in LA’s History

It’s well known that California is one of the most expensive states in the nation. A family must earn more than $60 an hour to afford a median two-bedroom apartment in the Golden State, according to the Out of Reach 2018 report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

Young tenants who live at Burlington Apartments in California join almost 100 families to kick off the Burlington Unidos rent strike and to protest unsafe living conditions and extreme rent increases. Photo by Timo Saarelma

In Los Angeles, as more than one-third of residents pay over half of their income on rent, residents find themselves deciding whether to purchase food, go to the doctor’s office, or pay for a roof over their heads. And the situation is getting worse. Each day, five rent-controlled apartments go off the market, says Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal, co-founder and media team member of the Los Angeles Tenants Union (LATU).

Despite the already unaffordable rents, costs continue to rise. In some instances, tenants are facing 80 percent increases. Such large rent surges are tantamount to eviction, says Rosenthal. And with the current cost of rent, “To be evicted in Los Angeles is to be evicted from Los Angeles,” she says.

It’s no wonder tenants are fighting back with all they have.

LATU and its local chapters have helped organize various tenant actions, like rent strikes, for residents to fight against unfair rent increases and unsafe living conditions, including the largest rent strike in Los Angeles’ history.

According to Rosenthal, it’s happening now at the Burlington Apartments in Westlake, where 200 people, mostly Latinx families with children, live. In January of this year, every household in the three-building complex was told their rent would be increased by 20 to 35 percent in April. This was in addition to a 10 percent rent increase imposed on tenants last year.

These additional increases came despite the buildings’ nearly intolerable living conditions, says Rosenthal—extensive water leaks; bedbug, roach, and rat infestations; broken elevators; and other health and safety concerns.

The tenants contacted Lisa Ehrlich of 1979 Ehrlich Investment Trust, which owns the property, but she refused to meet with them. The tenants even went to their city council representatives for help, but nothing came of it.

They eventually decided that their only option was to put pressure on Ehrlich. They formed an association—Burlington Unidos—and went on a rent strike to demand fair rent increases and repairs.

“Withholding rent, like withholding labor, is the only thing you can do to show your power,” says Rosenthal.

About 90 households are participating in the strike, says Trinidad Ruiz, an organizer with VYBE, a local chapter of LATU. The households are withholding a total of about $120,000 in rent each month.

Because it’s not easy, nor inexpensive, to work through the legal process to evict 90-plus households from their homes, rent strikes are an effective tactic, says Rosenthal. “Together you can win; alone you can’t.”

It’s been about four months since tenants began organizing, taking actions that include the rent strike and visiting Ehrlich’s community to protest and speak with her neighbors about the situation. But Ehrlich has begun a formal eviction process for the striking households.

Burlington Apartment tenants Maria and Robert now face eviction after losing their court case. The couple joined a rent strike after their rent was increased by more than $400 a month despite buildingwide issues, like hot water that shuts off daily. They plan to appeal the court’s decision. Photo courtesy of Trinidad Ruiz

So far, tenants have been successful in four eviction cases, but have lost two.

The tenants are prepared to go the distance, striking for years if needed. “They’re very brave and they have nothing to lose,” says Ruiz, explaining that the tenants have searched for other housing in the area, but haven’t found anything they can afford.

It took almost a year of rent strikes to get a Boyle Heights building owner to negotiate fair rent increases with his tenants after he had initially attempted to raise rents by 60 to 80 percent, according to StreetBlog LA. Tenants who live in a 25-unit building on 2nd Street, most of whom were musicians who worked a block away at Mariachi Plaza, organized a successful nine-month rent strike and won a three-and-a-half–year rental agreement that includes fair rent increases of 5 percent a year, and completion of apartment repairs. The landlord also agreed that when the agreement concludes, he will negotiate with tenants again.

How did the residents make it happen? Initially, the owner refused to meet with the families and even began formal eviction proceedings against those who hadn’t paid their full rents. But then the tenants organized and, in similar fashion to the action taken in Back Bay, Boston, went to the owner’s personal neighborhood and spoke with his neighbors. They even camped outside of his home.

After that, the owner agreed to negotiate.

“They won protections that are equal to rent control,” Rosenthal says. “By themselves they did the work that policymakers refused to do.”

A Million-Dollar Victory for Families

Tenant organizing and rent strikes can be a steppingstone to policy fights as well.

In 2014, the North Bay Organizing Project of Sonoma County, California, began knocking on doors to engage voters in the city of Santa Rosa. While the group hadn’t worked on tenant rights issues before that point, they came upon Bennett Valley Townhome residents, who were dealing with serious housing concerns. For years, they had been living in shoddy conditions with health-related concerns due to mold and bug and rodent infestations. And they were facing steep rent increases.

“They didn’t know that they could actually challenge [their] landlord,” says Davin Cardenas, the co-director of the North Bay Organizing Project.

Once they understood their rights, the tenants participated in a rent strike and sued the owners of the complex for damages for its substandard living conditions. Last year, the tenants settled with the owners of the complex for $2.75 million—the largest settlement in Sonoma County history. “They were really the families that brought us into the struggle. That ended up being a big victory for tenants,” Cardenas said.

Since then, the North Bay Organizing Project has fully immersed itself in tenants’ rights organizing, and earlier this year, the organization hired a tenant organizer to build out a countywide tenants union, says Cardenas. The organization has also taken on a rent control campaign at the city level. While the group was initially successful—the council passed a rent control policy in 2015—the policy was forced into a special election June 2017, and the effort failed by 700 votes, Cardenas said. The group is now gathering signatures to get the policy back on the ballot for the November election.

Getting a bill passed will especially help Santa Rosa residents who have been affected by last October’s wildfires. In December, a California provision that stops landlords from increasing rent by more than 10 percent after a disaster is declared will expire.

“All the rent increases are right at the limit of what is legally possible right now. If [landlords] could charge more they would definitely do it,” says Cardenas.

Indeed, some landlords tried to increase rents by more than 50 percent after the Santa Rosa wildfires in early October 2017. Tenants of a mobile home park in Pentaluma say they were facing a $500/month lot rent increase by the end of that month. The North Bay Organizing Project began working with the tenants, gathering signatures on petitions and holding a press conference detailing the price gouging. Tenants pushed back and were able to defeat those increases through public pressure, Cardenas says. It was the first post-fire victory for tenants.

Whatever policies the North Bay Organizing Project hopes to win, Cardenas says they will only be good to the degree they are enforced. Organized tenants who are willing to raise the alarm on landlords who are breaking the law will be essential.

It’s All Connected

As gentrification continues to grip communities far and wide, and as more people begin to understand the strong link between a person’s housing and their health, tenants in cities across the U.S.—like Minneapolis, Rochester, Syracuse, Washington, D.C., Houston, and Santa Rosa—are using rent strikes as a tactic to get their voices heard.

The decision to go on a rent strike doesn’t come without risks, but, as Rosenthal of LATU says, it’s solidarity that wins. “A rent strike is only as powerful as the number of people who are committed to it.”

Of course rent strikes aren’t the only way to gain the attention of absentee landlords and new building owners, as organizers in Nashville have shown.

Whether by rent strikes or face-to-face negotiations, reaching an agreement between parties often takes years. But a win brings power to tenants on both the building and city levels. Organizers like Cardenas say local victories go hand in hand with larger city and statewide efforts.

And many organizers agree.

“The work we do to support people on the front lines of eviction is really necessary to win any kind of policy,” says Matthews of City Life/Vida Urbana. “There really is a symbiotic relationship between the building organizing and the legislative organizing. If we don’t have laws that protect tenants, then people will just be evicted and displaced from the city and there will be no one to fight for legislation. But on the other hand, if we don’t have people affected going through a process of empowerment and speaking out at the local level, then we won’t get that legislation.

“It’s all connected.”

Obviously these people have no idea the cost of maintaining and owning a rental property.They pay no real estate taxes and face no liabiltiy living in a rental property but the landlord does.

These people are clueless.