As many of our founders, and readers, expanded their work to include building new affordable housing and looking at comprehensive community development and community building, so did we. But we’ve never forgotten the importance of organizing, or the importance of tenant protections.

For a while, however, the focus shifted to affordable homeownership, and strong tenant organizing and tenant protections seemed primarily limited to a couple of big dense cities and some highly progressive smaller urban areas like Cambridge, Massachusetts. Cambridge, as well as Boston and Brookline, Massachusetts, lost rent control in a statewide referendum in 1995, the first year I came to Shelterforce. I remember that while housing advocates put up a good fight and declared they would rebuild a tenants’ movement, the general sentiment from outside the state was lack of surprise, an expectation that this was just the way things were right now.

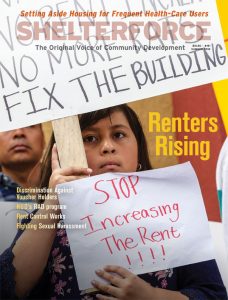

Except of course that history travels, if not in circles, then in spirals. With the much-belabored and fretted-over rise in the proportion of renter households after the foreclosure and financial crisis has also come a resurgence of tenant organizing—or housing justice organizing as many groups are calling it. Rent regulation is no longer being discussed as a vestigial holdover from a previous age, but again actively debated and organized for (here and here).

Many things look familiar about this movement. Goals like just-cause eviction protection, reasonable rents and rent regulation, basic housing decency standards, and fair housing protections; tactics like building- or landlord-specific tenant association organizing, public shaming, and rent strikes; and legislative campaigns for tenant protections driven by organized tenants.

But there are also different aspects to it. The foreclosure crisis disrupted the assumption of a forward progression from tenant to homeowner, making the two categories less separate and allowing some groups to organize both constituencies. There has also been a great spreading of awareness about models that are in between pure rental and pure home-and-land ownership, and today’s housing justice movement is in many places savvily combining organizing for tenant protections with organizing for community control of land and permanently affordable, democratically controlled housing models. This dual approach is unwilling to leave behind the vast majority of tenants in standard private rental housing or give up on a vision of making housing that is more stable and community-controlled to those for whom traditional homeownership is out of reach or undesirable.

Also thanks to that wave of foreclosures, there is now a proliferation of single-family rentals owned by larger corporations—even more distant than the typical absentee landlord of the 1970s. This provides new organizing challenges—and also opportunities for international solidarity, as shown by several joint U.S.-Spain actions against the private equity firm Blackstone.

There’s also a new group of people interested in housing quality; the health care sector. Black mold, lead paint, broken elevators, musty carpeting, pests, and insufficient heat—almost all of the most common maintenance problems that tenants organize around—also come with health effects. And so too, we have come to acknowledge, do burdensome rent hikes, unaffordable utilities, and eviction and displacement. While the interest of the health care sector in housing has largely started with financing for affordable units, the provision of legal aid to tenants and support for tenant protections is also in evidence, and tenant organizers should be sure not to miss organizations in this sector as potential allies in campaigns either against specific landlords or for policy change.

While the tenants’ movement has not been on the front pages for many years, it was never dead. And in a period of rising housing costs and income inequality, its resurgence is a welcome sign.

I would love to see a push to build allies out of groups traditionally seen as counter to, or at odds with, the tenant protection advocates. Developers and the homebuilding industry, for example, actually stand to gain by ensuring renters have stronger rights, but we need to work to identify where those intersections are. The advocacy crowd treating the development community as the enemy will never bring the results our communities need.