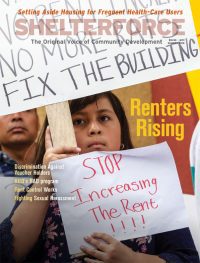

Victims of housing discrimination and advocates from the Statewide Source of Income Coalition gathered at the New York State Capitol Building in April to support a bill that would amend the state’s human rights law to include lawful source of income as a protected class. Photo courtesy of Ban Income Bias NY

The Housing Choice Voucher program, colloquially known as Section 8, seeks to eliminate concentrations of poverty and provide poor households with greater access to higher-opportunity neighborhoods. Even though research suggests that voucher holders prefer to move to neighborhoods with low poverty and access to quality jobs and education, they must first find a landlord who is willing to rent to them. This can be a challenge in places where landlords commonly refuse to rent to voucher holders, a practice known as “source of income discrimination.” To combat this practice, many states, cities, and counties prohibit discrimination against otherwise-qualified voucher holders.

A Failed Promise

Scholars find that vouchers have so far had limited success in breaking up concentrations of poverty and increasing access to opportunity. Theoretically, voucher holders can settle anywhere. In reality, however, recipients “are no more likely than nonsubsidized households to penetrate discriminatory market barriers and find rental accommodations in integrated living environments,” according to James H. Carr in his 1999 paper, “The Complexity of Segregation: Why It Continues 30 Years After the Enactment of the Fair Housing Act.” Although many voucher holders do end up living in moderate-income areas, most do not move far from their previous neighborhoods. Moreover, there are deep racial divides regarding which households are more successful in finding housing in non-poor neighborhoods.

One possible reason for the failure of the voucher program to achieve these goals is that federal law does not require landlords to accept vouchers; nor do most cities or states. This allows landlords to discriminate against potential tenants on the grounds of their “source of income.”

Voucher recipients are a subset of America’s very low-income households. Only about a quarter of eligible households receive housing assistance. Voucher recipients are more financially stable than their unsubsidized counterparts, not less. Studies show that when well-kept subsidized properties are located near other market-rate units and developments, they do not cause any loss in property values, or any increase in crime. Overall there is little to distinguish properties that rent to Section 8 recipients from those renting to other low-income tenants. Nonetheless, landlords commonly refuse to rent to voucher holders.

A recent study by the Fair Housing Center for Rights and Research found that in 2016 in Cuyahoga County, Ohio, African-American female testers with children who sought to pay rent with a voucher were denied housing 91.2 percent of the time. Similarly, the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law Inc. found in 2014 that Chicago housing providers discriminate against tenants based on voucher status 32 percent of the time. Ninety-one percent of landlords in Austin refused to accept Section 8 tenants and 94 percent of units in the right rent range were not accessible to voucher holders, prompting Austin to pass a source of income protection ordinance, which was later pre-empted by the state of Texas. A 2001 HUD study found that 31 percent of vouchers actually had to be returned because the recipients couldn’t find a landlord that would accept them—and in some markets that number was much higher.

[Related: The Answer–Can Prohibiting Source-of-Income Discrimination Help Voucher Holders?]

Voucher holders are disproportionately people of color, and that has led advocates and scholars to suggest that the refusal to accept vouchers is often a proxy for racial discrimination. The Cuyahoga study found that landlords who stated they did not accept vouchers were 20 percent more likely to treat African-American testers unfavorably or more stringently in other ways than white testers. Furthermore, families with children, the elderly, and people with disabilities are all also protected from discrimination under the Fair Housing Act, and are more likely to have vouchers. Thus, when discriminating against those with vouchers, there is often a disproportionate impact based on the tenant’s familial status, disability, race, or age.

Litigation arguing that this disproportionate impact violates the Fair Housing Act has been met with mixed results. Discrimination can be hard to prove. Yet in some cases these lawsuits have succeeded in forcing some local governments to adopt laws banning source of income discrimination. Because litigation has been only partially effective, dozens of municipalities have proactively enacted laws to protect voucher recipients from discrimination. Some of these laws generically prohibit discrimination based on lawful “source of income,” while others explicitly forbid landlords from turning away renters with vouchers or holding someone’s receipt of government assistance against them in housing decisions. Some ordinances exempt buildings up to three units; others up to five units; and others stick with only the Fair Housing Act exemption of an owner-occupied two-family home.

Meanwhile, Indiana and Texas have actually passed laws preventing cities and towns from passing these kinds of protections, prompting advocates to call for pushback against this kind of state pre-emption and more protections nationwide.

Effectiveness of Source of Income Protection

Early research shows promise for source of income anti-discrimination laws increasing the likelihoods of voucher holders finding a place to use their vouchers, moving to integrated neighborhoods, and moving to higher-opportunity neighborhoods. In 2001, Meryl Finkel and Larry Buron studied 48 public housing agencies and 2,600 voucher households, finding that, all else equal, the probability of successfully using one’s voucher within the program time frame (their definition of program success) was 12 percentage points higher in jurisdictions with a source of income anti-discrimination law. In 2012, Lance Freeman concurred, estimating voucher utilization rates increase by 5 to 12 percentage points when there is an a source of income anti-discrimination law on the books. A 2011 study for HUD, The Impact of Source of Income Laws on Voucher Utilization and Locational Outcomes, found that utilization rates were 4 to 11 percentage points higher in jurisdictions with these types of protection laws than in jurisdictions without. That study also found that poverty rates and voucher concentrations were 1 percentage point lower in those jurisdictions, and Black, Asian, and Native-American voucher recipients had proportionally 15 to 22 percentage points more white neighbors.

Opponents express concerns about distorting the rental market through additional regulation, though there is little evidence to show that the market is actually being distorted. Landlords also commonly express that they find the required inspection to be an administrative burden, which is one reason advocates for source of income protections also frequently call for universal rental registries and inspections. The courts have generally found that the purported administrative burden involved does not rise to a level that would warrant an exception from source of income protections.

Alone, source of income anti-discrimination laws will not instantly eliminate all the barriers that low-income families with vouchers face when looking for a place to live. Much of the success of such policies is dependent on their implementation and enforcement. As with other housing discrimination laws, the burden of enforcement largely falls on those being discriminated against. Few source of income protections include robust and proactive enforcement mechanisms; advocates are still figuring out what those would look like. The Equal Rights Center in Washington, D.C., which has had source of income protection on the books since 1977, found that in 2005, voucher holders were still discriminated against 61 percent of the time. Concerted education, outreach, and monitoring between 2005 and 2011 brought that figure down to 28 percent.

Meanwhile, protections for voucher holders are spreading across the country, and courts regularly uphold their validity. The evidence suggests that these protections are helping, but to really make a substantial difference, the next step will be figuring out enforcement.

What’s going on in Minneapolis? Last I heard, they passed a source-of-income anti-discrimination ordinance, which I would guess provided a more explicit protection for HCV holders than Minnesota’s general source-of-income protection. The ordinance went into effect this past May, but it looks like a judge struck it down in June. Any thoughts how that will play out?

Hi Rose, with the caveat that I’m horrible at predicting the future, and I’m not familiar with Minnesota state courts, I would say that the judge’s decision is likely to be reversed on appeal. The Judge’s decision is based on a weird constitutional theory that says it violates due process because the law is simply too irrational to exist. That’s a tough argument to make in any case (think about all the silly laws we have), but it is particularly difficult here because the judge 1) ignored the fact that these laws exist in lots of places, not just Minneapolis, and 2) the judge disregarded the city’s reasons for passing the law. As far as legal theories go, this one isn’t particularly strong, so I tend to think that the decision will be reversed on appeal.

My land lord of 11 + years have been so patient with me. Two years ago they let me know they needed their property back. I told them okay, I will put in my request to move, and start looking. I’ve been looking ever since! Even tried porting to another state and it was just as hard to find a place with all the credit checks and income checks they’re doing, despite me having a voucher. I need help, seriously. My landlord has already taken me to court, thankfully the case was dismissed. They didn’t take me to court for non payment of rent, because they get their money like clock work, on both ends for the past 11+ years. They was looking to evict me, because I was taking too long to find a place. I had to cancel the port, and start back looking here in BK, NY. Financially was the biggest reason, I cant afford to start over in another state at this point, looking for a place was hard enough, to look for a new job and getting back on my feet would’ve been even harder for me to do. Looking in another state was proving just as difficult to find a place to live as NY was 2 years ago. So I decided to give my home town another try. The Housing agency had made changes, like raising the 2 bedroom standards price, and I was also told that I can get an apartment that’s priced more than the standard, as long as I can pay the difference. That was unheard of 2 years ago, but is now allowed in NY. So I’m looking out here again, and already I’m finding the discrimination and the using the “credit score”, and the “you must have a 60k income” or higher to get the apartment. No matter what the apartment price is, if you have a voucher or not, this is just another excuse to use against section 8 voucher holders. Purely an excuse because, we can only look for an apartment in the lower price ranges, as it is. The Government pays the bulk of the rent, while the tenant pays 30%. Unless the utilities are included in the rent, the tenant pays gas and electric and their 30% share of the rent. So in defense of voucher holders looking for a place to live, what REALLY does a credit check, or making a 6 figure income have to do with us paying our portion of rent, and paying our bills on time? We will pay our portion and bill’s faster than a person not receiving a subsidy, otherwise we can get kicked off the program. How many voucher recipients are really willing to risk losing a housing subsidy that we really NEED in order to keep a roof over our heads, by not paying our bills on time, or at all? Not me! Now here I am struggling and stressing to find a place, as close as possible to where I presently work and live, before my landlord ends up giving court another try. The last thing I need is an eviction, which will make it way more difficult to find a place. Laws MUST be changed in NEW YORK, because the discrimination is ridiculous out here. The rents are sky high, in NY (& all of its 5 boroughs) yet section 8 voucher recipients are still given a hard time to find a place. Then landlords complain about how we take too long to move out, but we can’t move, until we are approved for a new place by our housing agency (or we’d lose our voucher) but finding a new place, at the same time, is extremely difficult. Why? Because nobody wants to take the section 8 tenants in NY anymore! I’m proof! I feel like I’m stuck in these peoples house! I would love to get off their property, but I cant find anything! I really need help! 2 years looking for a place, in and out of NY! This is a nightmare.