This article is part of the Under the Lens series

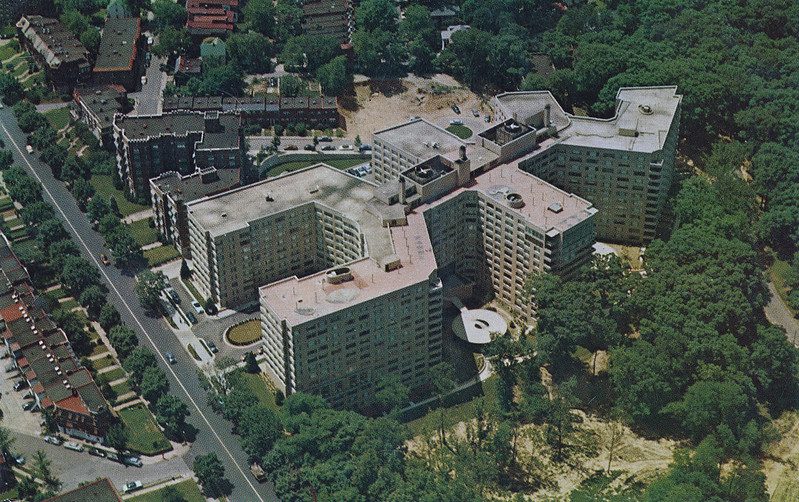

The Woodner, Washington’s largest apartment complex, as it appeared in a postcard in its earlier incarnation as a hotel. Photo by Streets of Washington via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0 Deed

When Zuleima Santos, 24, graduated from college in May, she couldn’t find housing in D.C.’s increasingly unaffordable housing market. So she moved back into her parents’ one-bedroom apartment on Park Road in the Columbia Heights neighborhood, which they share with her two younger brothers.

For a few years, Santos had been helping her family and other tenants in the rent-regulated building deal with the owner, who had filed a hardship petition asking for a 32 percent rent increase. (A loophole in the city’s rent law allows landlords of rent-regulated units to increase rent higher than would otherwise be legally allowed.)

A local community development group helped negotiate the increase down to 12 percent, along with promises of repairs. But the landlord then put the building up for sale, putting all the buildings’ residents, including Santos’s family, under threat of displacement.

Unlike tenants in other cities, the residents had some leverage in the sale. D.C. is one of a few American cities that have a “Tenant Opportunity to Purchase” law requiring that tenants receive notice when their buildings go up for sale and giving tenant associations first opportunity to purchase. It also gives tenants the right to assign or sell their rights to third parties and use this as the basis of negotiation for repairs or affordability.

This means that, in theory, tenants in Santos’s building had an opportunity to buy their building. But Santos says the largely low-income residents of this five-floor, 54-unit building, most of whom speak only Spanish, were at a disadvantage from the beginning.

The sale price of the building was $10 million—far more than residents could realistically raise on their own, even with some city subsidies. And although the local Latino Economic Development Center was providing information to residents, it was still hard for them to understand their legal options and the best path forward, Santos says, pointing to a need for earlier and deeper outreach about TOPA between community organizations and residents.

The challenges point to a larger problem with D.C.’s TOPA law. While it has in some ways been a powerful tool for tenants rights and has inspired bills proposed by tenant activists around the country—including a bill in New York modeled on D.C.’s—a lack of city resources and investment has dampened its revolutionary potential.

How D.C.’s TOPA Law Works

D.C.’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act is the oldest such law in the United States. The TOPA law was enshrined in its current form in 1980, after decades of urban renewal and gentrification led to residential displacement. Under the law, property owners selling or demolishing a building must offer the building to a registered tenant association at the appraised value or at a reasonable market value.

The law also allows tenants to sell off their purchase rights to third-party landlords or assign them to groups that align with their interests, including nonprofits who wish to purchase the building and help tenants steward it. These rights give tenants leverage to negotiate with incoming landlords for repairs and greater affordability. In rare cases, the law provides a path to co-owning their building with their neighbors.

A November report commissioned by the city of D.C., and produced by the Coalition for Nonprofit Housing and Economic Development (CNHED), sheds light on some of these challenges using data from 2006 to 2020. It shows that buildingwide purchases under TOPA are rare, the result of a lack of attorneys, education, and crucial subsidies that building residents need before a purchase can happen. But it also shows that the law has empowered tenants, spurring the creation of tenant associations and providing tenants leverage when developers want to buy their properties.

Data compiled for the report shows that the number of units purchased by tenants or nonprofit partners and securing affordability through TOPA peaked in 2013, when 2,397 units were purchased. From 2014-2018, there were an average of 1,469 units purchased annually. In 2019, that number dropped to 415 and in 2020, that number was 342.

TOPA can lead to a range of results within one building. At Santos’s building, for instance, most tenants agreed to a buyout from the landlord. She says only about 10 families remain, including hers. For those remaining tenants, repairs, including replaced windows, new floors, and additional security and cameras, were negotiated.

But conversations about buying the building, which Santos had some interest in, did not advance, chiefly because of cash. “For a community like this one, specifically, TOPA is very restrictive, because you have to come up with your own money,” Santos says. “In reality, their opportunity to buy wasn’t there from the beginning.”

A Need For Organizers and Attorneys

Under TOPA, tenants can purchase their building by forming a tenant association. This means adopting bylaws and electing officers, and then signing up a majority of residents. The ideal outcome of a TOPA process to many tenant activists is a kind of shared ownership of the building, in the form of a limited equity cooperative in which the building’s resale value is restricted to prevent housing speculation.

But according to Amanda Huron, a professor at the University of the District of Columbia who has written about tenant cooperatives, these arrangements were far more common in the 1980s and 1990s, when property values were lower.

“They very rarely choose the limited equity cooperatives option at this point in time,” Huron says of tenants. (The report’s time frame doesn’t reflect the period in which cooperatives were more frequently developed, according to Huron.)

Tenants lack capital, but they also lack technical expertise to negotiate for buildingwide improvements or purchases. “Tenants don’t always know how to respond,” Huron says. D.C. funds tenant organizers through nonprofits that are alerted by the city when TOPA notices are sent to buildings. But “there’s more sales happening than there are organizers funded by the city to keep up with,” Huron says.

According to the CNHED report, “Tenant organizations, often stretched due to high demand and capacity limitations, have a significant impact on the success of TOPA.”

The report says that between 2006-2020, community organizations provided support to 421 tenant groups, comprising 45 percent of all buildings, and 55 percent of all units that received a TOPA notice ahead of a sale.

“Lack of information about the process was a common theme among tenants,” according to the report. Despite the additional leverage, tenants still face a power imbalance once a TOPA notice is issued. Tenants sometimes don’t know who their purchaser is or how to get in touch with them, as they’re “typically shielded by an LLC,” which tenant organizations and attorneys can help them uncover.

Technical assistance doesn’t just mean housing organizers, but attorneys. Huron says that TOPA has become its own cottage industry in D.C., with some attorneys boasting their specialization in the law. But these attorneys are still outpaced by the need. “The limited number of attorneys specialized in TOPA cases poses a challenge,” the CNHED report says, “as the workload and demand exceed the available legal expertise.”

The report also warns that some tenants have been misled by developers who pressure tenants to sign away their TOPA rights prematurely. The problem was most prevalent in smaller and more run-down buildings, and it was exacerbated during the early months of the pandemic when community groups were unable to visit tenants in person due to safety protocols.

Promoting Tenant Associations

Despite a lack of resources, TOPA has led to flourishing tenant associations. In the 15-year period covered by the CNHED report, 425 tenant associations were formed as a result of TOPA. Tenant organizing has blossomed in that time frame, from 37 percent of buildings with a TOPA notice forming an association in 2006-2010 to 50 percent in 2016-2020.

“Naturally, tenant associations more often view buildings as home, and not just a real estate deal,” the report says, leading to negotiations that focus less on maximizing payments in the form of buyouts for some tenants but pushing for quality of life improvements.

Often this takes the form of preserving affordability, and many projects have utilized federal programs like Low-Income Housing Tax Credits or project-based Section 8 as well as the city’s Housing Production Trust Fund and rent control laws to accomplish this.

In 7,712 TOPA units, the extension of existing rent control protections set to expire was the main affordable housing protection negotiated, and 7,774 units utilized Low-Income Housing Tax Credits.

As a result, “TOPA made a meaningful impact on improving the District’s affordable housing stock and reducing displacement, especially in the more recent years,” according to the report. There were 19,170 units in the period studied where tenants were able to either negotiate improvements with an incoming owner or purchase the building outright. This amounts to 51 percent of cases where tenants received a TOPA notice.

Because entire buildings can sell their TOPA rights to developers, there have been concerns that developers can simply bribe tenants en masse and raise rents. But the report found this rarely occurred buildingwide. Only 403 units encompassing 22 properties—out of 295 properties in the study—had buildingwide buyouts.

[RELATED ARTICLE: How It’s Working: Laws That Help Tenants and Nonprofits Buy Buildings]

TOPA at Scale: The Woodner

Smaller apartment buildings are at even more of a disadvantage when it comes to using TOPA to either buy a building or negotiate to improve conditions. This is because their scale limits the financing tools they can access, like low-income tax credits or bonds. Half of all buildings studied in the CNHED report had fewer than 15 units. For smaller buildings, there’s less interest from nonprofit purchasers, the report found.

Yet TOPA isn’t just a challenge to implement at smaller apartment buildings; large apartment buildings have their own challenges. At 1,100 units, the Woodner is D.C.’s largest apartment complex and home to generations of tenants, including seniors who have lived in the building their entire lives. Organizers and tenants have been dealing with an increase in eviction filings as a result of the pandemic since D.C.’s eviction moratorium lapsed in 2022. Many Woodner residents work in hospitality, among the hardest hit industries at the beginning of the pandemic. That put them in arrears, and as federal eviction prevention funds lapsed, they have not been able to dig their way out.

“Since the moratorium ended we’ve had about 200 or so filings. It’s just been consistent. Every week there’s a few more filings. They’re trying to push people out as quickly as possible,” says Sierra Ramírez, a resident and organizer with the Woodner Tenant Union. The group was founded in the early months of the pandemic, with neighbors communicating over WhatsApp.

The group does outreach and provides political education, mutual aid, and eviction defense to its members. They’re currently battling 70 active eviction filings, Ramírez says. The Woodner is rent-regulated, but because allowable increases are tied to inflation, this has still meant increases of $100 or $200 upon lease renewal. (D.C. also allows vacancy bonuses in rent-regulated buildings, so when tenants are priced out or evicted, landlords can raise rents by 20 percent.)

Ramírez says that advocates advised the tenant union to formally register with the city so they could exercise their TOPA rights in case the landlord decided to sell. But they realized a sale was unlikely to happen. Even if the landlord wanted to sell, Ramírez says, the city did not have enough attorneys or organizers to help the thousands of residents at the Woodner understand their options.

“Pretty quickly we learned that was not going to be a viable option for us,” she says. “The city was supposed to provide access to funding and financing for people to be able to do this. It’s just not remotely available as is needed.”

In addition to the lack of resources, she says, even a shared ownership model would likely mean paying back debt used to buy the building, forcing compromises.

“The latter model of providing subsidization via loans has benefited financial intermediaries, corporate or nominally nonprofit, but it is much less generous to tenants, who still need to pay rents that are high enough to cover the costs of day-to-day operations as well as a mortgage that, however generous the terms, still needs to be paid back,” she says.

“I really want to promote community-based self-determination,” she adds. “The TOPA process as it is sets you up to have some significant challenges if you’re trying to create community autonomy and do things in a way that’s going to be very unfamiliar to what banks and lenders are used to.”

Zuleima Santos learned about another group of tenants who used TOPA to turn their building into a housing cooperative. She plans to move to the building next year.

“Hopefully next year I will have a home I can afford,” Santos says. But she’s still worried about her family: Her parents never accepted a buyout from the landlord, but fear they’ll be displaced anyway. Even if they had accepted a buyout, Santos worries that the money wouldn’t have helped them in the long-term.

The numbers look good on paper; many people are getting between $35,000 and $40,000. But Santos says many of the tenants getting buyouts in her building—low-income immigrants like her family—may not know where to invest it or how to avoid scammers, and may see their federal benefits reduced or eliminated since the money will count as income and change their tax bracket.

Even if they hold on to the money, after they pay moving costs and a higher rent in a new building, it may not last as long as they hope. It also may not be enough for a downpayment on a house in D.C.’s tight market.

Watching tenants fundraise to buy a smaller apartment complex showed her how formidable the odds were for her longtime home on Park Road to become community owned.

“It took about 20 educated, full-career, active members to support the movement of just fundraising and getting everything together for basically $2 million,” Santos says. “And if you put that next to a lot of immigrant Latino families with very low income, parents that work two to three jobs for 12 hours a day, kids to take care of, it leaves the question of how can we tackle TOPA if we need $10 million to purchase this building?”

This story was published through a collaboration with Shelterforce and Next City. Next City is a nonprofit news outlet that publishes solutions to the problems that oppress people in cities, inspiring social, economic, and environmental change through journalism and events around the world.

I’d love to hear how such a law could be made more effective. Certainly, it seems like DC’s law is better than nothing, but one wonders how we could better design a law for today’s profit driven housing market…