This article is part of the Under the Lens series

The Racial Wealth Gap—Moving to Systemic Solutions

A Pittsburgh family celebrates becoming homeowners, with the help of the Oakland CLT. Photo by Peeler Photography via the Oakland Planning and Development Corporation

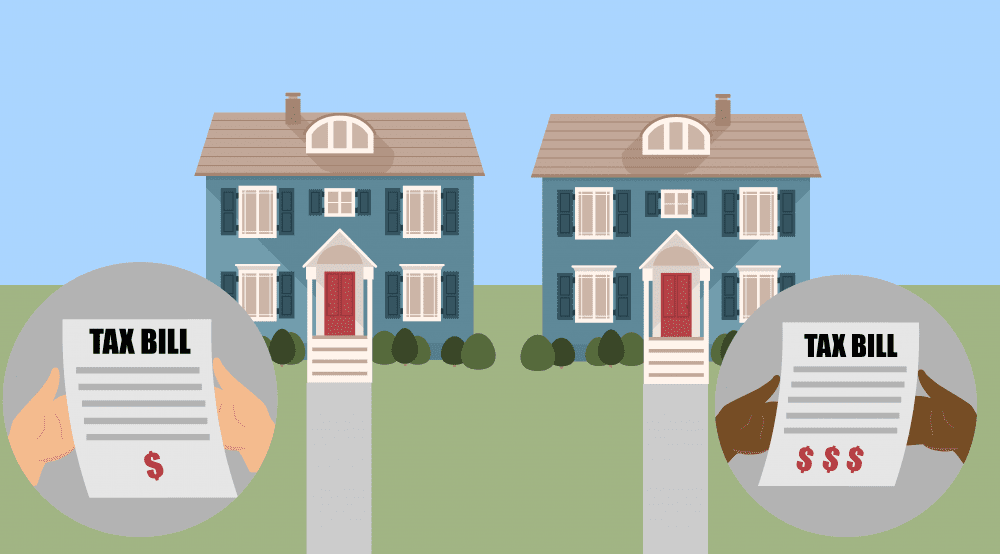

Homeownership remains one of the most common tools employed to try to help Black families build intergenerational wealth. However, for reasons authors in this series have detailed, simply achieving the dream of buying a house often does not generate the results that it generates for white families. Households of color tend to own homes of lower value and have a higher percent of their assets in home equity, feeding into the disproportionately low share of wealth held by Black and Latinx households.

Housing advocates say that without significant policy and practice changes, both the racial homeownership gap and the racial wealth gap will remain wide for decades to come.

Race-Conscious Programs

One step is to actually target specific groups for support, rather than assuming that programs targeting low-income homebuyers will be sufficient. “When you are a policymaker, you are thinking about things that are good for all … but we didn’t get here because of policies that were good for all,” stated Chrystal Kornegay, executive director of MassHousing, during a webcast in December 2021 hosted by the Urban Institute. MassHousing is an independent, quasi-public agency that lends over a billion dollars annually to produce and preserve affordable rental housing and to create homeownership opportunities for low- and moderate-income borrowers.

“You can’t have a race-conscious solution that doesn’t actually include race in it,” she added.

Although programs to help people of color get into homes have been around for decades, Laurie Benner, associate vice president of programs at the National Fair Housing Alliance, says the racial homeownership gap is still prevalent because “none of the programs have been racially explicit.”

There’s an idea out there that “because of fair housing laws . . . you can’t say ‘This program is for this category of people,’” Benner adds, “but in fact, lenders can do it. They can create a loan program just for Black people, or Latino people, or for AAPIs, Indigenous people, and so on.”

Through the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, financial institutions are permitted to develop special purpose credit programs (SPCPs) to meet special social needs and benefit disadvantaged groups. When properly designed, SPCPs can play a crucial role in promoting equity and inclusion, building wealth, and removing barriers that have contributed to housing instability and residential segregation.

So the resistance isn’t legal, it’s optics—a throwback to colorblind ideals. “We’ve seen lending programs for people with disabilities, and no one is outraged by that,” explains Benner, “but if a lender were to introduce a mortgage program specifically for Black or Latino people, it would almost certainly be subject to legal challenge.”

Benner adds that some banks have homeownership programs targeting economically disadvantaged groups, but the programs are place-based and “operating very quietly.”

“We need some of the big banks to just start doing it” more openly, says Benner. “Once [the big banks] cross [that] hurdle, smaller community lenders and CDFIs can do these kinds of programs. We just need a couple of people to jump first.”

Income as Well as Appreciation

Besides calling on the banking system to change its policies, housing groups are also adjusting their homeownership programs to go beyond just getting people into houses. For example, New Orleans Habitat for Humanity has launched a pilot program that will allow a family to purchase a multifamily property and use the rental income to help them qualify for one of Habitat’s zero-interest loans.

When Marguerite Oestreicher, executive director, presented the idea to the Habitat board, one of the members told a personal story. “She shared how her family moved from being wage earners to having true wealth, and the first step of that journey was her dad purchasing and renovating a double, which became the first of many investments,” recalls Oestreicher.

Durham Community Land Trustees (DCLT) in Durham, North Carolina, is also introducing second units into the mix. Initially the idea came from the difficulty of purchasing land to create affordable rental units in this market, says Sherry Taylor, DCLT’s asset manager, so they looked at their own portfolio. But they realized the additional cash flow could also be a way to support the land trust homeowners. So far the CLT Plus One program is still in its planning phases, but DCLT intends to provide property management services for the rental units, at least for the first several years, passing most of the rental income on to the homeowner. “Our new homeowners won’t be out there by themselves,” says Taylor.

Flexible Grants

Oakland CLT homebuyers. Photo courtesy of Oakland Planning and Development Corp

In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Oakland Planning and Development Corporation (OPDC) is a community development corporation that produces homes for sale through its community land trust. The homes are offered at a rate that is deemed affordable for people who are at 80 percent or below of the area median income. However, executive director Wanda Wilson says, the organization wants to expand who they can help.

“We’re specifically finding that with Black families in our community, many are renting,” Wilson explains, “but there’s been a lot of rising rents. We applied for funding specifically to provide grants to Black and Indigenous people of color to be able to buy a home from the community land trust.”

Wilson explains that the BIPOC buyers OPDC works with are generally lower-wage workers who cannot qualify for the full cost of a mortgage and therefore need additional gap funding. OPDC has also found that BIPOC buyers have less savings and are therefore concerned about home maintenance should something need to be repaired.

[Read more about how community land trusts relate to asset building.]

There have been many, many downpayment assistance programs, but what’s different about the program OPDC has created is that the cash assistance is flexible, meaning it can be applied in many different ways to support a given household. Depending on their income, participants receive between $21,000 and $31,000. This amount is larger than the typical sum that downpayment assistance programs provide, which is around $7,500. There are several options for how families can use the funds beyond a downpayment, including building savings for housing repairs, paying down debt to improve their credit score, or covering closing costs not covered by other first-time homebuyer programs. It’s individualized to the homebuyer’s needs, but the menu of options focuses on challenges that tend to fall more heavily on BIPOC homebuyers.

The grant program is funded through the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency. It’s in its early stages, is application based, and enrolled its first seven participants last fall.

According to Wilson, what OPDC’s program does differently is specifically address systemic inequities experienced by Black and Indigenous people, and other people of color. “We basically want to be proactive, to make sure that BIPOC families can have the opportunity and it is not just white families that we are serving,” she says. “Without a proactive approach to serving BIPOC, we run the risk of only serving white buyers.”

Better Mortgages

The Indianapolis Neighborhood Housing Partnership (INHP), a housing development and nonprofit lender, is constantly looking at the data to see how it can help the homebuyers and borrowers it works with, most of whom are households of color, and advance racial equity. This has led to experimentation with a number of new products.

One of the most popular is called the mortgage accelerator. Very simply, it’s a mortgage where the interest rate is so low (currently around 1.25 percent) that it can have a term of 20 years instead of 30 for the same monthly payments a homebuyer would be making on a typical 30-year mortgage. The mortgage is paid off faster, resulting in quicker building of equity in the home, and the homeowner saves many tens of thousands of dollars in interest payments. INHP is able to sell these loans on the secondary market to CRA-regulated banks despite their low interest rate. Because there’s no downside to the homeowner, basically the only INHP borrowers who don’t use the mortgage accelerator are those who are participating in a downpayment assistance program that requires a 30-year mortgage, says Joe Hanson, executive vice president for strategic initiatives at INHP.

Especially with prices rising, INHP also wanted to enable its borrowers to buy into higher value neighborhoods, so they built on the mortgage accelerator to create the market expander. With this product, there’s the typical 20-year low-interest loan, and then a second, 10-year no-interest loan after it, giving homebuyers more buying power with the same monthly payment (in fact the payment drops a little for the last 10 years). The second mortgage relies on philanthropic investment and is held on INHP’s books, so there is a limit to how many INHP can make, but the principal of giving families access to more neighborhoods is still exciting.

And finally, knowing—again from the data—that homeowners of color are both more likely to be given higher interest rates and less likely to refinance, INHP has launched a refinance product, hoping to stem some of the wealth extraction those high interest rates represent. “If people are paying more interest than they have to, what’s our opportunity to lean into that disparity and effect change?” says Hanson.

Refinancing people out of overly high interest rates is mostly straightforward, but INHP’s commitment to racial equity means they know they also need to think about appraisal bias as they launch this product. The organization hasn’t figured out entirely how yet, but Hanson says they at least intend to replace standard full appraisals with alternative methods, possibly exterior-only evaluations. But, he notes, it is difficult to know what to do with the legacy of racism that actually has affected values in a neighborhood, as perceived by buyers, quite aside from bias from appraisers themselves. INHP hasn’t figured out what, if anything, it can do about that yet, but is actively seeking solutions.

With all of these products it’s a work in progress, says Hanson. “We’re trying. We’re listening. We’re using data and research. It’s OK if it doesn’t hit right out of the gate. We continue to adjust.”

Changing Underwriting

Changing underwriting standards is often seen as a strategy to help families of color increase access to homeownership because the standards affect the terms and size of loans. For the same reason, underwriting is also a factor in how well homeownership builds equity for homeowners of color.

The Federal Home Loan Bank of San Francisco and the Urban Institute recently launched a partnership called the Racial Equity Accelerator for Homeownership, which is looking at several ways to make homeownership work better for households of color. Along with removing historical bias from AI algorithms and developing ideas for products that will help homeowners get through short-term repair issues, the partners are also are looking at underwriting from two angles: ways to incorporate rental payments and utility payments into underwriting, and different ways to consider student debt when underwriting. Currently, “we’re not looking at the full picture when assessing creditworthiness,” says Teresa Bryce Bazemore, president and CEO of FHLBank San Francisco.

While there has been discussion for a while about how to bring rental payment history into credit scores themselves, which would be a significant improvement in racial equity, some organizations are not waiting. INHP looked at the HMDA data that showed that credit scores were the major factor keeping households of color out of homeownership, and in the summer of 2021 launched a rent-focused underwriting product, for which underwriters use rental history to establish a track record of regular payments. While they also do have other criteria, such as accounts in collection, the numerical credit score itself is not a factor in approvals for this product.

Interest in the product was high, says Hanson, and they got hundreds of inquiries. Interestingly, about 10 percent of those inquiries came from people who actually qualified for a conventional mortgage with INHP, but hadn’t known it. “It was a perceived barrier,” says Hanson. “And just the fact of advertising that we have creative solutions, allowed them to take the chance and explore it, [and] then they found they didn’t need this special program, they could participate in the system as it’s currently designed.”

But others did need that product, and INHP now has about 50 families engaged in the process of working toward a mortgage through the rent-focused route. So far, it has not been an easily standardized approach. Establishing rental history when people have had roommates or paid in cash, for example, is complicated. INHP has been figuring it out on a case-by-case basis, and is now helping all of the participants work through other issues, such as judgments and accounts in collections, before the underwriters feel confident the borrowers will be able to safely sustain a mortgage. “It’s called rent-focused underwriting, not rent-only underwriting,” notes Hanson, who hopes that “the success of our program can be a demonstration that rental history can be a good proxy for successful conversion into homeownership that might generate more momentum in terms of creating system change.”

Scaling Together

In the summer of 2021, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and a coalition of civil rights organizations and leaders launched an initiative called 3by30. The coalition is led by a steering committee made up of executives from the Mortgage Bankers Association, the NAACP, National Association of REALTORS, National Fair Housing Alliance, National Urban Institution, and the Urban League. The mission of 3by30 is to create 3 million new Black homeowners by 2030.

Along with helping more Black people become homeowners, however, the 3by30 plan also focuses on sustainability, aiming to ensure that current Black homeowners are not vulnerable to foreclosure. To do this, the collective will focus on providing adequate education to homeowners, especially those who are first-timers, so they can understand what’s involved with homeownership before making a purchase. There are also plans to guide those homeowners away from predatory loan products and connect them with resources and emergency assistance funds in the event they do run into financial trouble.

“Nothing has been done on this scale before,” says Benner. The National Fair Housing Alliance is one of approximately 100 stakeholders under the coalition. “Of course, communities have always had housing counseling and community development programs, and those groups are intimately familiar with the local challenges. They do a phenomenal job, especially considering that their funding sources are continually at risk.

“[The difference],” adds Benner, “is the Black Homeownership Collaborative (BHC) wants to focus on the big systemic issues to create a foundation of equity to build on.” Some of the focus areas include:

- Supporting more funding for downpayment assistance, particularly for first-generation buyers, and for fair housing enforcement;

- Supporting racially explicit solutions;

- Reevaluating the credit scoring system and exploring the use of alternative and non-traditional credit sources;

- Exploring using rental housing payment data and housing payment shock data to assess borrower risk;

- Removing bias from computer algorithms connected to lending and other housing-related decisions;

- Analyzing and supporting efforts for inclusive zoning practices;

- Reinvesting in historically redlined areas; and

- Creating an infrastructure for smaller mortgage loans

“If we can remove some of the structural barriers, the local communities won’t have a constant uphill struggle for properly resourced neighborhoods full of successful, healthy, financially secure individuals and families,” says Benner.

A uniform voice on advocacy and public policy efforts is one of the biggest tenets of the BHC, she adds. “The value that the collaborative brings is the collective advocacy power of the organizations. We are taking the voices of state and local organizations to Congress; we are exerting influence on policymakers and corporate entities with a unified message. That’s what it’s going to take [to close the homeownership gap].”

Correction: The market expander product was misnamed in the first version of this article.

|

Help keep us strong by becoming a Shelterforce supporter. |

Enjoying the series here about how homeownership alone won’t close the racial wealth gap. There are more parts to the problem that have to be addressed.

In DC, our company (Flock DC), launched a foundation that awards downpayment assistance that IS racially conscious. We specifically work to get our BIPOC, first-time homebuyer neighbors into their new homes quickly, and with a very simple application process. In our first year, the birdSEED Foundation had four families close on homes.

Many of the people that we chose for the downpayment assistance could not close due to credit issues, so we see that system as a huge barrier for BIPOC folks in their homebuying and wealth generation journey.