This article is part of the Under the Lens series

The Racial Wealth Gap—Moving to Systemic Solutions

Photo by Wakila via iStock

The recent explosion of interest in housing’s role in perpetuating the racial wealth gap has been stunning. Unfortunately, most accounts of this role are wrong because they misrepresent the actual dynamics and processes at work. While correctly focusing on the iniquitous forces of racism, the authors of these accounts—the most prominent of which has been Richard Rothstein in The Color of Law—fail to comprehend how fundamental racism is to the very essence of America’s institutions. When it comes to the role housing has played in the perpetuation of racialized disparity, deprivation, and dispossession, race matters even more than many already think.

“The Racist Theory of Value”

Markets, like all institutions, are “socially constructed.” This means they reflect the prevailing social values and biases of the society that creates them. Thus the supposed “rationality” of the market is merely an expression of what is valued (or, even more importantly in this case, devalued) by market participants. So, in a fundamentally racist society such as the United States, where a profound and tenacious anti-Blackness is especially salient, such abhorrent beliefs “powerfully infect market values, such that what appears as neutral and objective is, in actuality, merely an expression of racist attitudes, subjectivities, and imaginaries,” as I have written in the Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City.

To understand how this dynamic plays out in regard to the low market value of urban real estate, consider the insights of two of America’s most eminent and perceptive Black scholars (who, it should be noted, have been on different sides of many contemporary debates, but agree on this). Adolph Reed Jr. observed in 1988 that “Careful examination of the bantustanization in American cities makes it impossible to distinguish purely racial from purely economic imperatives. … [T]he logic of markets is socially and political constructed and … race enters into social and economic life in complex and indirect ways. … [For example] parcels of land occupied by minorities are underutilized and ripe for redevelopment because the presence of minority populations [itself] lowers market value.”

Likewise, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor elucidated the key dynamic this way: “People talk about the free market as this racially neutral, color-blind space within which the invisible hand of supply and demand dictates what does and doesn’t happen. But that’s so incredibly naïve. The market is us. The market is a reflection of our values. And when it comes to property, race is at the very center.”

Reed’s and Taylor’s insights remind us of an insidious process that has been well understood for decades: Property values—especially residential property—are negatively affected by racist beliefs and attitudes. In fact, as far back as the 1950s, housing activist Charles Abrams identified a “racist theory of value” which suggests, as the geographer Eliot Tretter recently observed: “African American neighborhoods, households, and bodies were [seen as] simply less valuable and desirable [in market terms] than those of whites.” Property, and especially housing valuation, is not race-neutral, with equity accruing equally to all.

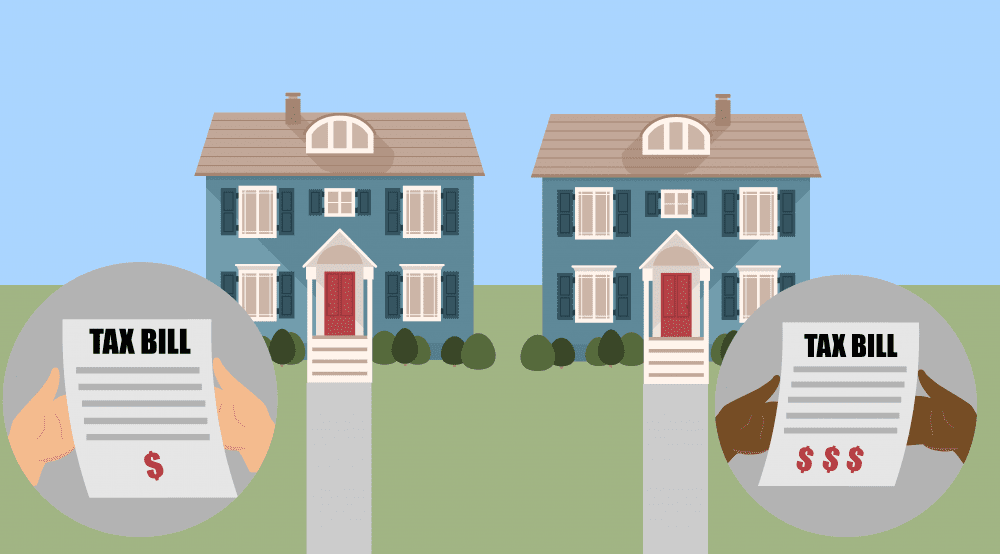

American society continues to be stricken by this pestilence. Some important recent evidence comes from a study by the Brookings Institution that is a useful corrective to much of what has been written recently on race and housing. It takes seriously the idea that markets are socially constructed, building from the recognition that “the value of [market] assets is influenced by implicit societal cues,” such as the implicit biases we all harbor in our subconscious. Applying this insight, it found a significant “devaluation of housing assets stemming from racial bias throughout the [housing] market” as “anti-Black beliefs [negatively] distort the value of [these] assets.” Even after controlling for various factors, “a square foot of residential real estate is worth 23 percent less in neighborhoods where half the population is Black” compared to similar neighborhoods with few or no Black residents. (The values were a shocking 50 percent less without controlling for other factors).

Black homeownership rates hover in the low 40s, 30 percentage points below the rates for whites—a level remarkably unchanged over a half century. Beyond the vast disparity in the rate, Taylor points to what is perhaps an even more significant racialized disparity: “[E]ven for the 40 percent of the Black people who do come to own their own homes, it doesn’t function in the same way. Property in white hands is valued more than property in Black hands. So even when Black people own property, it still does not accrue in value in the same way or at the same rate.”

Again, we see the pernicious “racist theory of value” at work.

Some Implications

So what does centering the “racist theory of value” tell us about the role housing plays in the racial wealth gap? Nearly everything. Most importantly, the prevailing (or conventional) wisdom—which Rothstein’s The Color of Law popularized but that extends well beyond it—has wrongly pinned the blame on various (especially mid-20th century) collective racist actions. This ignoble list includes the familiar litany of racial zoning, racial covenants, discriminatory real-estate industry codes, and, most notoriously, the actions of the federal government like redlining. I call this focus “state blaming.”

But the real culprit here has always been the underlying racist values that exist prior to these actions. Shifting our analytic lens in this way reorients the focus toward the actual root cause (the racist residential property market), and away from its symptoms—the policies and programs undertaken to protect property values from the self-fulfilling “racist theory of value.”

Continuing to obsess over these specific racist policies and practices—undertaken some 60 to 100 years ago—as the key determinates of contemporary racialized disparity, deprivation, and dispossession is a serious mistake. In fact, the same pernicious effects of the “racist theory of value” have played out over and over again in the same familiar pattern, from the Great Migration to the present day in areas where Black people have settled or been forced to settle, first in central cities, then in the outer parts of cities, moving next to inner-ring suburbs, and, of late, even increasingly beyond. Discussing so-called “opportunity neighborhoods,” Edward Goetz gestures toward this reality when he says, “all one needs to do is look at how previously favored places lose their ‘opportunity’ when they lose their white residents.” Shockingly, only 19 out of 1,036 (1.8 percent) majority-Black ZIP codes are today considered prosperous.

Toward Justice

The most important upshot of shifting the focus of blame from racist government actions to the racist property market is that it points us toward more efficacious remedies. One of the key lessons from historian David Freund’s important book on the racial biases of real estate valuation—what he aptly calls “colored property”—is that it exposes the severe limitations of the go-to solution of conventional wisdom—increased market access for those denied it. This approach, as Freund points out, “assumes a model of analysis in which a pure, discrete market for housing exists, a market that operates outside of people’s assumptions about color and property.” In reality, however, the housing market is imbued with racial bias— greatly constraining the value of market access for Black people.

The most obvious concrete takeaway is that increasing traditional homeownership by merely expanding Black access to the conventional housing market is unlikely to do much to close the racial wealth gap (though homeownership may advance other desirable goals, for sure). Instead, we should look toward housing options that are less tied to market values, such as community land trusts and limited-equity cooperatives.

More fundamentally, when we look to close the racial wealth gap, we must remember that the role played by the consumption of goods and services, even housing, is ultimately far less important then how we choose to organize production in the broader economy. Of particular importance here is who owns and controls productive investment capital—and on what terms. Conventional analysis generally cannot see beyond consumption. Hence it tends to blame the state (i.e., racist government actions) because of government’s direct role molding this consumption, rather than the far more consequential issue of how the broader American economy functions in highly racialized ways in its production of goods and services.

Racial capitalism thus must be the most intense focus of our efforts. If we are to reduce racial inequality significantly, efforts to restructure the nature of ownership and control of economic production within our system of racial capitalism must be absolutely central. The crucial aim here is to rebuild, comprehensively, the community wealth held by communities of color, especially Black communities (as recently called for by the policy platform of the Movement for Black Lives).

Only when we have done that restructuring can we begin to bend the arc toward racial justice in any serious way.

Editor’s Note: A version of this piece first appeared in The Journal of Race, Ethnicity and the City.

|

Help keep us strong by becoming a Shelterforce supporter. |

These are thought-provoking insights, thank you, but as I see it in a city which is predominately Hispanic in a large urban city, even if our city was 100% Hispanic, we still would see widening structural economic disparities. Why? Because our long-term “Vision Framework”, “urban planning”, & “economic development” model have only led us to become among the nation’s poorest, economic segregated cities.

In a black-white urban scenario, I dare say similar results would play out as well.

Who are the racists? We are. Who adopted these polarizing impacts & outcomes? We did. Thus, we need a different lens to better understand the crucial role adopted economic policies produce, something I’ve asked for a long time but which has resulted in no interest whatsoever. Planning ideology has not been taken seriously. We’ve imitated the colonizer all too well, to the point of blindness & indifference.

Very well thought-out and written