This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Lucy Engelman/ Resistance Communications

The housing sector has experienced a number of upheavals in the past couple of decades.

- In the 2000s, financial institutions created new types of mortgages that facilitated unsustainable home price increases, while also developing new financial products tied to those mortgage payments. Global financial markets circulated these products to investors with seemingly insatiable appetites for these risky and profitable assets. The foreclosure crisis and wider recession that these practices precipitated wiped out half of all Black wealth while expanding the racial wealth gap between white and Black households to at least 20:1.

-

Three Takeaways- Deregulation and tax policy starting in the 1970s allowed financial markets to become entwined with real estate markets.

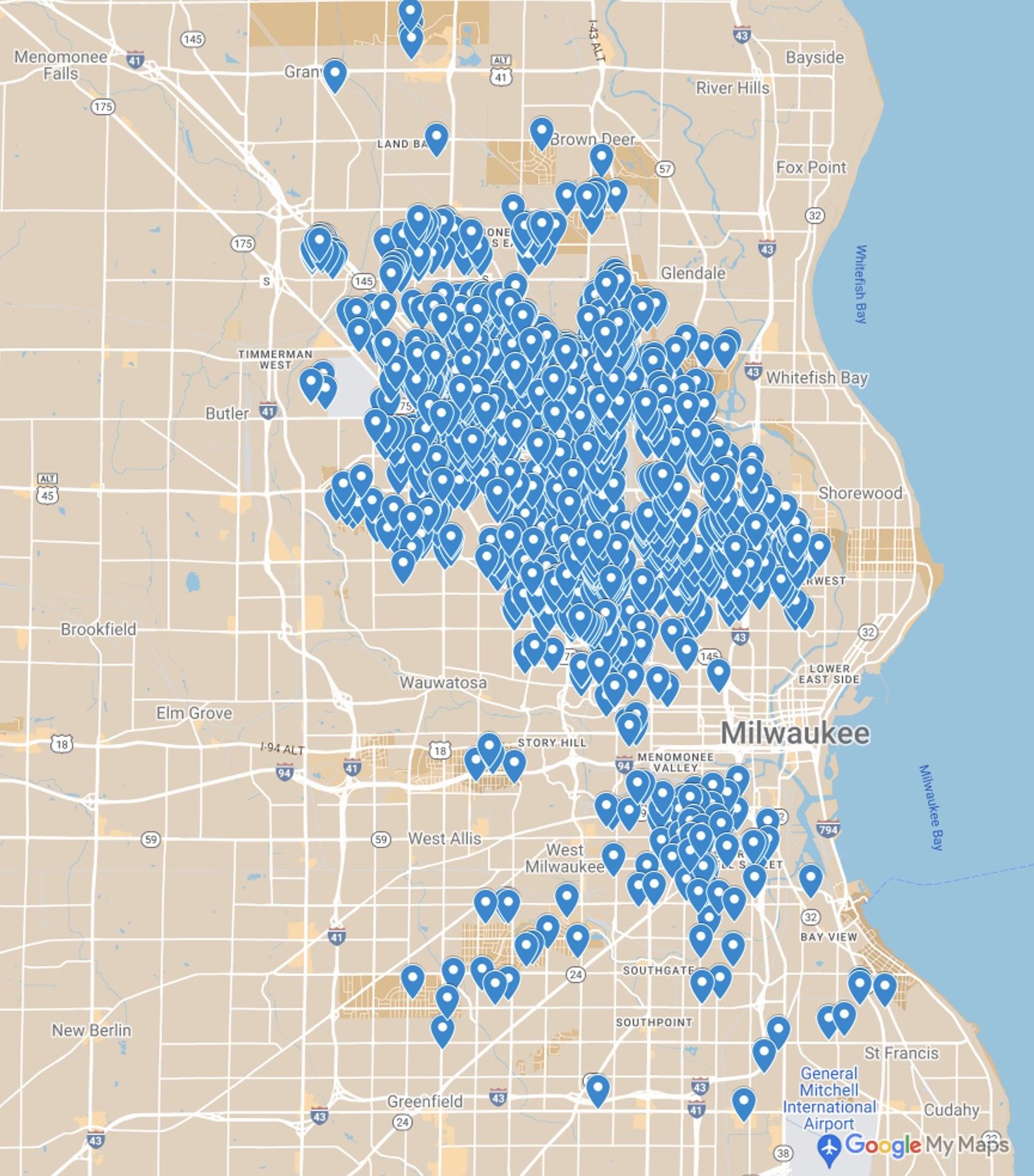

- Financialized housing looks different in different markets—highly leveraged purchases of apartment buildings in New York City, evicting tenants from rent regulated properties in San Francisco, buying up foreclosed homes to rent out in the Sun Belt, or reintroducing predatory contract sales in weaker markets.

- Responses must include regulation, strengthening the role of the public sector in providing housing, and strengthening tenant organizing.

In the wake of the 2008 housing crisis, national investors capitalized on widespread foreclosure, damaged household budgets and creditworthiness, and low home prices to resuscitate the practice of contract selling—in which a buyer essentially takes on all the responsibilities of homeownership, but doesn’t take the title until their loan is paid off, meaning they can lose everything they’ve spent over one missed payment. This was once thought to be relegated a time when housing discrimination was legal and common; it was often the only way Black households, who were denied mortgages, could try to buy homes.

- In that same time period, but in other markets with a higher demand for housing, large institutional investors created a new “asset class” from the glut of foreclosed homes, purchasing thousands of previously owner-occupied single-family homes and converting them to rental. Targeted neighborhoods often found their housing markets largely controlled by a few wealthy, remote actors.

- And during the pandemic, large corporate investors have continued to dominate some markets by purchasing a significant portion of the homes there.

What all of these seemingly disparate developments have in common is that they are manifestations of the long-term process of the financialization of housing, a term that describes the increasing tendency for owners and investors to value housing as a financial asset, like stocks or bonds. This process increasingly divorces housing from its purpose as shelter by using it to generate profits in financial markets.

The financialization of housing is part of a long-term transformation of the economy, and so it has to be understood and analyzed not as a phenomenon of specific markets, such as expensive cities or supply-constrained regions, but as an emerging set of investment strategies and management practices that present real challenges to affordable housing advocates, tenants, and community development organizations.

The Origins of Financialization

Most broadly, financialization describes a transformation of the economy—like deindustrialization in the mid-20th century. Financial actors, financial institutions, and financial logic have increasing influence within our economy, and they rely heavily on profit-making strategies that derive from control of a scarce resource rather than from the production of something of value. This often includes control of land, but could also include, for example, intellectual property, natural resources, or financial capital.

Financialization affects how different sectors of the economy operate, and the housing sector is no exception. Housing and land have always been connected to finance and financial markets and subject to their imperatives and rationalities, though to different extents over time. Financialization of housing is about the integration of financial markets with real estate markets, a process that is best illustrated by historical comparison. In response to widespread home foreclosure and the banking system collapse of the Great Depression, New Deal reforms regulated finance and separated commercial banking that serves the needs of businesses and households from investment banking, which is inherently speculative and risk-prone. Decades later, beginning in the 1970s, U.S. policymakers and regulators relaxed these controls. Interest rate caps on loans were eliminated, paving the way for more profitable and riskier lending, such as subprime loans, which have higher interest rates but are accessible to borrowers who are considered “riskier.” The federal government led the way for “financial innovation,” for example, when Fannie Mae issued the first Collateralized Mortgage Obligation in 1983, a novel type of tradable security that is tailored to different investors’ appetites for risk and which deepens the connections between financial and real estate markets. As real estate markets became more volatile throughout the 1980s, the federal government responded by expanding the role of financial investors in managing the crises that followed. During the Savings and Loan crisis in the late 80s and early 90s, for example, banking institutions held delinquent and defaulting real estate loans that threatened the solvency of both the banking system and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. In response, the federal government pioneered new markets for novel types of financial assets tied to housing, including investments based on delinquent and other “high risk” loans. Finally, tax policy changed to further encourage capital investment in real estate.

The financialization of housing is independent from market conditions, though it continually interacts with them. In the COVID era, institutional investors have once again ramped up purchases of single-family homes, leading some observers to suggest that suboptimal rates of housing construction are causing this type of investment. Undoubtedly a relative lack of new housing in many markets influences the timing and placement of these investments, but these specific market conditions are not required nor are they a direct cause for financialization to proceed apace.

Time- and place-specific market conditions—such as low inventory and vacancy rates, rising prices, or, alternatively, weak demand and decreasing populations—can affect how financialization manifests, but longer-term structural transformations are facilitating financialization everywhere. For example, in expensive cities with lots of demand for housing, such as New York City and San Francisco, investors have purchased multifamily rental properties with expectations of rapidly increasing rents. Investors in New York are aggressively reinterpreting rent regulations to impose all allowable rent increases, pushing the legal boundaries of the law. Similarly, in California, investors are wielding the Ellis Act, originally designed as a tool for owner-occupiers to take properties off the market, to evict existing tenants and reposition the properties for higher-paying residents. In the suburban geography of the American Sunbelt—places like Atlanta, Phoenix, and Las Vegas—investors have purchased previously owner-occupied foreclosed homes and transitioned them into rental properties, rewriting boilerplate lease agreements in ways that shift risk onto renters and communities.

In markets with weaker demand and lots of vacant housing, housing financialization takes the form of national investors resuscitating housing practices that have long been used to exploit Black homeowners, such as contract selling. Buyers of homes on contract frequently find themselves with unlivable housing conditions and pay usurious rates and fees, only to ultimately lose their housing anyway.

Financialization does not require any one particular set of market conditions, but rather depends on structural conditions like financial deregulation, tax policy, and inequality as it unfolds across diverse regions.

Financialization of housing does depend on housing scarcity, but it’s important to recognize that housing scarcity is produced in multiple ways, including by financial actors themselves. It’s not an inevitable condition financial firms are merely taking advantage of. Indeed, creating and maintaining housing scarcity through hoarding housing, gatekeeping housing, and evicting people from housing is a central preoccupation of financial investors. State-imposed austerity measures that prioritize short-term deficit reduction over functional social programs consistently reduce state support for housing, which in turn increases housing scarcity. And an attitude toward financial risk that prioritizes support to the banking and financial system above keeping people housed also produces scarcity.

Take the case of Starwood Capital Group, a product of a 2015 merger between Starwood Waypoint Residential Trust and Colony American Homes that created a new investor firm which at the time owned 30,000 homes. Colony American Homes had begun purchasing homes after the 2008 foreclosure crisis through multiple channels, including bulk sales from government sponsored enterprises, like Fannie Mae, when prices were low and there were large numbers of foreclosed homes. The homes, called “distressed assets,” were considered to present system-threatening risks to the banking and financial system that had financed them. The model of selling them off with an eye to lenders’ balance sheets rather than their role in housing people had been pioneered two decades earlier in the aftermath of the Savings and Loan Crisis. The federal government created the Resolution Trust Corporation in 1989 to get foreclosed homes off banks’ books by passing them off to private capital partners, as opposed to stabilizing the homeowners and tenants in them, as had been done in the Great Depression. The precursor to Colony American Homes, Colony Capital, was one of those private capital partners.

This example demonstrates that the process of the financialization of housing has played out over several decades, is driven by state policy that redistributes risk onto households, communities, and cities, and has created new market spaces for investment in housing as financial assets. This is all independent of specific urban housing market contexts.

Financialization is contested, and organizers, advocates, and practitioners have been dealing with it for decades.

The Financialization of Housing on the Ground: Implications for Practice

The financialization of housing makes securing decent and affordable housing harder in several ways.

First, it reduces transparency. The legal structure of the limited liability corporation (LLC), which the IRS granted more favorable tax status in 1988, simultaneously insulates the individuals who ultimately benefit from ownership from personal liability and from regulatory scrutiny, and therefore LLCs are often the preferred legal tool of real estate investors. It is common for each property to be owned by a separate LLC, which makes tracking patterns of common ownership time-consuming and in many cases impossible. The opacity of ownership presents clear obstacles to effective regulation of housing codes and conditions and makes it harder for tenants and organizers to identify common beneficial owners and hold them accountable. To address these issues, tenant advocates and others have called for more transparency in property law, as well as comprehensive property or rental registries that would require landlords to disclose their portfolio holdings and management contacts. [Editor’s Note: Several articles in this series will get into this in more depth.]

Second, it makes it very hard to maintain affordability. Tying real estate to financial markets means treating housing more like financial assets, which investors expect to continually rise in value. In the Bronx, for example, apartment building sales prices have consistently outstripped how much income they generate from rents for decades, a product of treating these buildings as financial collateral for loans that owners use to extract equity. Investors deploy investment strategies with names like “distressed assets,” “opportunistic investments,” and “value-add strategies,” all of which are designed to deliver returns on investment well above long-term historical averages for real estate and other financial assets. Returns of 20 percent are plainly inconsistent with providing affordable and decent housing. When housing is used as a financial asset, those returns are generated through additional fees, reduced maintenance, and aggressive tenant screening and eviction policies. Simply put, large returns are generated on the backs of tenants.

Third, another clear research finding is that housing financialization increases housing instability. In Atlanta, for example, large owners, and institutional investors in particular, were found to file evictions more frequently. The business model of a large owner that can absorb turnover and vacancy costs in pursuit of extracting maximum rent across a portfolio is different from that of owners whose model involves long-term relationships with tenants.

Just as the financialization of housing has unfolded over several decades, addressing its problems and root causes will almost certainly be a similarly long-term effort. Even though the struggle has a long horizon, we can resist financialization and build a world in which we meet people’s housing needs, instead of letting housing meet capital’s needs.

One set of interventions includes increasing regulation of housing in ways that thwart the strategies of investors who seek to own and manage housing as a financial asset. To the extent that existing land use regulation erects barriers to competition in housing markets, which facilitates the rent-seeking that underpins financialization, these rules of the market should be changed, such as exclusionary zoning in wealthy neighborhoods that prevents affordable housing from being built. A reinvigorated fair housing enforcement agenda, at the federal, state, and local levels, is a crucial objective since financialization affects households of color especially. This enforcement agenda should also include more assertive regulation of the financial institutions and products that are extracting returns from housing, such as through the work of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Other regulatory interventions include the already-mentioned rental registries that make relations in property more transparent, aiding organizing efforts and bolstering policy efficacy. Measures that directly regulate the profit levels that investors can extract from housing, such as rent control and good cause eviction, thwart the excessive rents that can be extracted when housing instability and scarcity are high.

Regulation tends to be reactive and highly dependent on sustained enforcement, however, and so other strategies are necessary. At all scales, we must reorient policy and other collective action away from privatization, austerity that further erodes public investment in housing, and predicating housing production and provision on its ability to deliver private profits, even if we expect housing as a for-profit venture to continue for the foreseeable future. This requires local and state housing agencies to prioritize public and democratic control of public money, land, and housing. Local and state governments, public housing authorities, and mission-driven nonprofit housing organizations must be acquisitive with regard to land and buildings, and always resist the privatizing of public land and property. Existing affordable housing programs, such as the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program, should be a logical and relatively more manageable target for exercising leverage over owners to reduce housing instability and eviction.

When engaging in private-public partnerships for constructing and preserving affordable housing, regulatory agencies should write contracts that ensure long-term affordability and that prioritize public control over the property. Planners and other practitioners should embrace and expand the use of tools that can protect housing from speculative investment long-term, such as community land trusts.

Finally, and perhaps above all, financialization is a political problem that requires a political response. There is no solution to housing problems that doesn’t run through an empowered constituency of people and communities who work collaboratively to realize a common goal of decent and affordable housing for everyone and who make demands on the state for achieving such a goal. Historically, this has manifested through robust tenant movements that are intertwined with broader struggles for civil rights. Therefore, governments at all scales should adopt policies that facilitate tenants’ right to organize and wield their collective power to strike and make decisions about their housing conditions, analogous to labor organizing.

Given that the financialization of housing is a product of a larger economic transformation, fully curtailing it will depend on wide-ranging societal changes that reduce inequality and increase the capacity for people and communities to wield political autonomy—something else an empowered constituency can fight for.

|

With the support of readers like you, Shelterforce has continued to expand the ways we break down what’s happening in the community development world. Help keep us strong by becoming a supporter today. |

Benjamin, I enjoyed your article about the Financialization of Housing. I often think about the issue of affordable housing and how rental housing will never help those who should be concerned with generational wealth accumulation that can be used to educate, house and feed the next generation. in Philadelphia there are approximately 16,000 affordable rental housing units in a market where 70,000 are searching for an affordable option. Why not put more energy into creating opportunities and programs that lead to ownership instead of lifelong rentals. If we could teach young persons the basics of the tax laws and the potential rewards of home ownership, over time would the goal of freedom and independence be more desirable than life long renting. There used to be housing programs in Philadelphia that renovated homes, sold them at a discount and allowed lower income persons to begin to achieve the beginnings of wealth accumulation. You get to keep more of your hard earned lower income wages when you own instead of rent. You can borrow against your equity to educate your children and grand children. I don’t believe that the percentage of those at and near the poverty level will ever change unless all the energy that presently goes into pushing for more affordable rental housing changes and the goals become more in line with exploring the potential benefits to society if we all owned housing instead of so many of us renting housing for all of our lives.