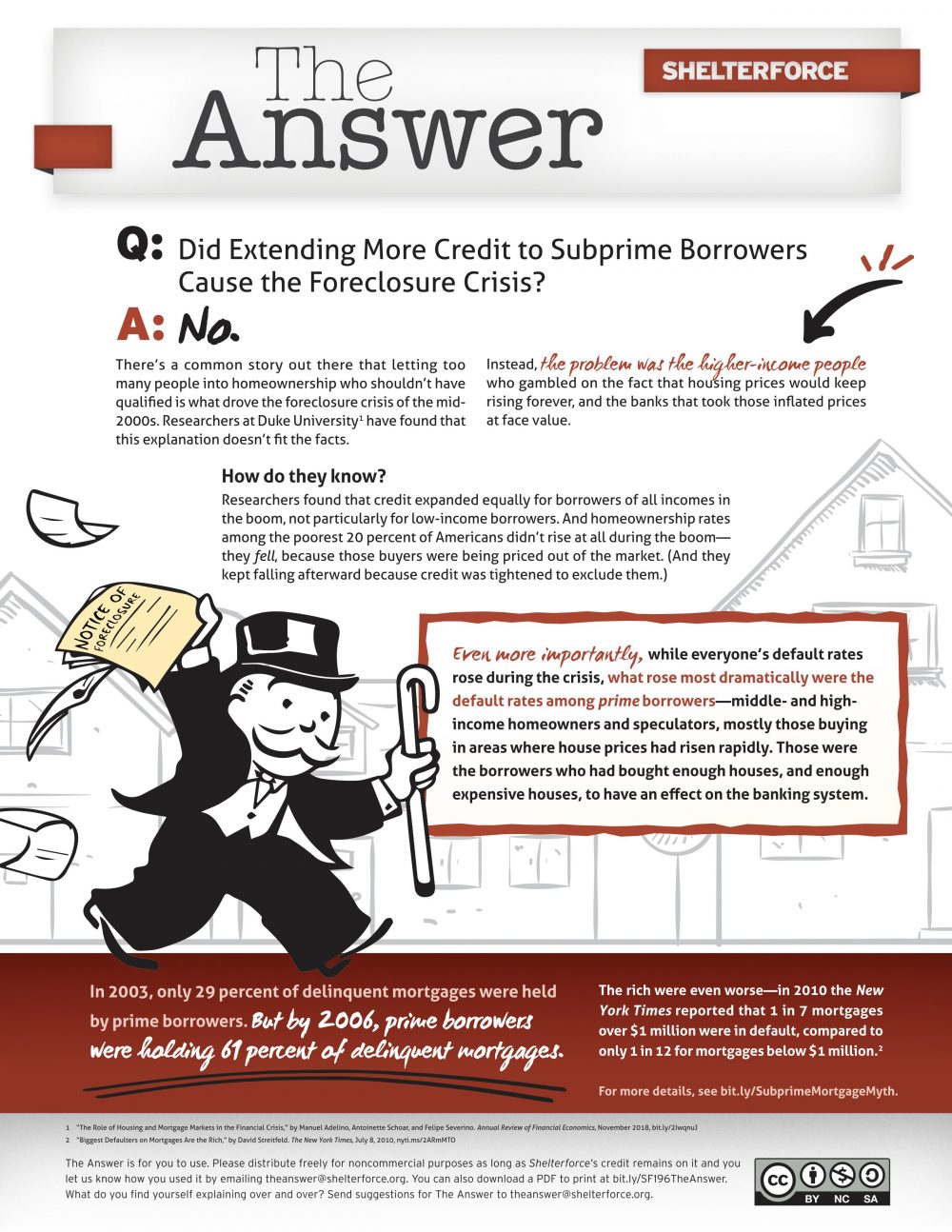

A: No.

There’s a common story out there that letting too many people into homeownership who shouldn’t have qualified is what drove the foreclosure crisis of the mid-2000s. Researchers at Duke University have found that this explanation doesn’t fit the facts.

Instead, the problem was the higher-income people who gambled on the fact that housing prices would keep rising forever, and the banks who took those inflated prices at face value.

How do they know? Researchers found that credit expanded equally for borrowers of all incomes in the boom, not particularly for low-income borrowers. And homeownership rates among the poorest 20 percent of Americans didn’t rise at all during the boom—they fell, because those buyers were being priced out of the market. (And they kept falling afterward because credit was tightened to exclude them.)

— Even more importantly, while everyone’s default rates rose during the crisis, what rose most dramatically were the default rates among prime borrowers—middle- and high-income homeowners and speculators, mostly those buying in areas where house prices had risen rapidly. Those were the borrowers who had bought enough houses, and enough expensive houses, to have an effect on the banking system.

— In 2003, only 29 percent of delinquent mortgages were held by prime borrowers. But by 2006, prime borrowers were holding 61 percent of delinquent mortgages. It was even worse for the rich—in 2010 the New York Times reported that 1 in 7 mortgages over $1 million were in default, compared to only 1 in 12 for mortgages below $1 million.

For more details, see bit.ly/SubprimeMortgageMyth.

Comments