This article is part of the Under the Lens series

The Racial Wealth Gap—Moving to Systemic Solutions

Activists from NoCap advocating for student loan forgiveness. Photo courtesy of NoCap

For Jonah Vincent, the importance of getting a college education was emphasized throughout his entire childhood by his parents, his school, and the culture in general. “They keep telling people … the most important thing that you could do in this life is to get your education and become somebody,” says Vincent. “So when they tell you, ‘Hey, to get this thing that you’ve been told you need your entire life, you got to take this $10,000 loan every semester,’ you’re not going to say no.”

Vincent grew up in Raleigh, North Carolina. His mother worked as an accountant, his father a social worker. They made enough to raise a family and meet their needs, “but we didn’t have excess money,” says Vincent, who’s the founder and director of NoCap, a youth-led organization that organizes around issues like criminal justice reform, voting rights, and student debt forgiveness.

While he did receive a partial scholarship to attend North Carolina Central University, and his mother took out a loan to help pay for some of his and his twin brother’s college education, it wasn’t enough to pay for it all. “My parents made a little too much money for me to be able to qualify for anything, so I had to take out loans to go to school. And so that’s when I started to understand like, holy shit, this is $30,000 in two years.”

By the time Vincent earned his master’s degree in music theory and composition, he had taken out more than $100,000 in student loans. Now, years later, his loans continue to hang over his head like a dark cloud. With interest, he expects he’ll have to pay back about $227,000 for his college education.

Vincent’s story isn’t unique. There are 45 million Americans who owe more than $1.7 trillion in private and public student loan debt. Over the past decade and a half, the cost of college has ballooned, forcing students and their families to take on even more debt to pay for a postsecondary education. And Black graduates like Vincent are saddled with much higher levels of student debt than white graduates.

The moment they receive their bachelor’s degrees, Black graduates have on average $7,400 more student debt than white graduates, according to Brookings. Four years after graduation, the Black-white student debt gap more than triples to $25,000. And this debt weakens the ability of Black households to build generational wealth.

“Student debt exacerbates and interacts with the already appalling racial wealth gap in the United States,” says Emily Hirtle, policy associate at Americans for Financial Reform. “We know that the typical white family has eight times the wealth of the typical Black family, and five times the wealth of the typical Latinx family. So it’s important to not forget that Black and Latinx [families] start from a much less privileged position wealth-wise.”

So what explains the large disparity in student debt, and what can we do to address the student debt crisis and close the racial wealth gap?

Types of Postsecondary Institutions

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), in the 2018–19 academic year, the average net price of attendance (total cost minus grant and scholarship aid) for first-year, full-time undergraduate students attending 4-year institutions was $13,900 at public institutions, compared to $27,200 at private nonprofit institutions and $23,800 at private for-profit institutions.

Who’s taking out loans? Sixty-six percent of students attending public four-year colleges, and 69 percent of those attending private nonprofit institutions, according to NCES.

That rate is much higher at the more expensive for-profit institutions, where a staggering 86 percent of students took out loans.

Black students are about three times more likely than white students to attend for-profit institutions, which tout quick programs, flexible schedules, and online learning. These programs look extremely attractive to children in lower-income communities who often don’t have access to college counselors.

“For-profit and predatory colleges . . . target Black students and other students of color,” says Charlotte Hancock, senior director at Generation Progress, a youth-centered research and advocacy group. “These institutions often result in high debt burdens that are more difficult to pay off.”

For-profit institutions also have notoriously low graduation rates. A 2019 look at students who began their education in 2013 showed that only 26 percent of students at for-profit schools graduated within 6 years, compared to 63 percent at public institutions and 68 percent at private nonprofit institutions. For Black students, only 19 percent graduated from for-profit institutions within 6 years. Therefore, much of the debt incurred by students at for-profit schools does not come with the added earning power of a degree to help with repayment.

The debt carried by students at for-profit institutions is compounded when they attend graduate school. Twenty-eight percent of Black graduate students were enrolled in for-profit graduate schools compared to just 9 percent of white graduate students. While private nonprofit schools can be as expensive as or more expensive than private for-profit institutions, the lion’s share of growth in graduate school attendance has been at private for-profit schools.

Graduate School Debt

Black students are attending graduate school at increasing rates, and they’re also twice as likely as their white peers to accrue student debt.

One reason for this has to do with the Higher Education Reconciliation Act of 2005, or HERA. Before HERA was enacted, graduate school students could only borrow up to $20,500 for their schooling. But after HERA’s passage, graduate students were able to borrow up to the cost of attendance via the Direct PLUS loan program. According to Brookings, this may have disproportionately increased graduate school attendance among Black students, who on average have less familial wealth to draw upon than white students.

Because of this, the authors of the Brookings report believe HERA unintentionally played a role in expanding the racial wealth gap. Furthermore, the Brookings researchers believe the 2008 financial crisis may have pushed Black students to enroll in graduate school in hopes of expanding their skill set, and improving their chances of securing a good-paying job.

For Vincent, attending graduate school was a must.

“When my parents graduated from college or when they graduated from high school, they were able to get a job that could pay them to be able to buy a house, buy a car . . . and build a family essentially. For us, grad school is almost a necessity . . . to even be able to sniff $60,000 a year,” he says.

Vincent remembers visiting his university’s financial aid office when he decided to pursue a master’s degree in music theory and composition. A loan officer told him that he wouldn’t have time to juggle a job and his intense coursework. “The student loan officer that I had was telling me to go ahead and max out my loan so that I didn’t have to work during grad school.”

“Go ahead and pay your rent, and pay your bills with this money,” the officer told him. “And that way you finish school with good grades.”

Vincent did finish school with good grades, and a lot more debt.

Deferring Life

The transition from school to the workforce was swift and difficult for Emily G., who asked us to withhold her last name for privacy reasons. As a recent graduate in her late twenties, she considers herself lucky that she was able to find a job after graduating from Drexel University with a master’s degree in creative arts therapies at the beginning of the pandemic. First, she worked in a psychiatric hospital, assisting individuals in crisis. She soon picked up a second job as a family support specialist at an online charter school because the first job wasn’t paying enough. All the while, she was struggling with post-grad depression. “I didn’t realize how bad it was until more recently, because I’m on the other side of it now.”

Emily has since left those jobs and started working as a counselor for the Philadelphia public school system. Despite the praise that workers like her received during the height of the pandemic, little has been done to alleviate the hardships that student debt levies on workers in essential sectors. Federal student debt payments have been paused since the beginning of the pandemic, so Emily has not yet had to make any payments, but with $150,000 in debt looming over her, Emily dreads what those monthly payments will do to her budget. “I have a community around me and we throw around the same $30 in a circle, but it’s not easy, nor does it feel great . . . I do service work, so for myself and other folks . . . working in public schools or hospitals or other agencies, your base pay starts at $35,000 to $40,000 with a master’s degree,” she says. “You’re barely getting by.”

The disproportionate attendance rate at graduate school, followed by difficulties in the labor market, which include an increasing racial wage gap, add up to a huge accrual of interest on loans. That interest is responsible for 25 percent of the racial disparity in student debt. Forty-eight percent of Black graduates see their undergraduate loan balances grow after graduation compared to just 17 percent of white graduates.

Additionally, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis found that while many white graduates received financial assistance from their families after graduation to supplement their income, pay off student loans, and assist in wealth-accruing activities such as buying a home, Black graduates often transferred part of their post-graduation income to assist their families.

That rings true for Emily, who’s been helping her family. Her mother, who is a teacher, was given a diagnosis of an autoimmune disease several years ago. With her heightened vulnerability to COVID-19, her employment options as an educator are severely limited by the pandemic.

“My parents have a lot of debt . . . my mom has a lot of school debt and she really doesn’t make that much money and it’s hard for her,” says Emily. “Maybe it’s not to the same level as some of my other friends who may be helping their parents with rent, but as far as certain bills or other things that they want to do that they maybe don’t have, I’ll just give them the money for it . . . I want them to have other things to look forward to.”

A House, Someday?

Student debt has long-term consequences for Black households.

“I want to go buy a house, but I’m looking at that student loan number and I’m like, there’s no way anybody’s going say, ‘OK, here’s an extra $600,000 to go buy a house right now,’” Vincent says. “It’s not going to happen. So, it definitely plays a role in planning, family planning, and just being able to be a part of society. It’s that dark cloud that just hangs over your head.”

Emily G. has similar concerns. “At some point, I do want to buy a home and I do want to have my own land. And I do want to farm and different things like that. But a part of having the debt is how far am I going to have to push that off? A part of having the debt is, you know, I do want to have a family . . . but I’m also like, I can barely afford myself.”

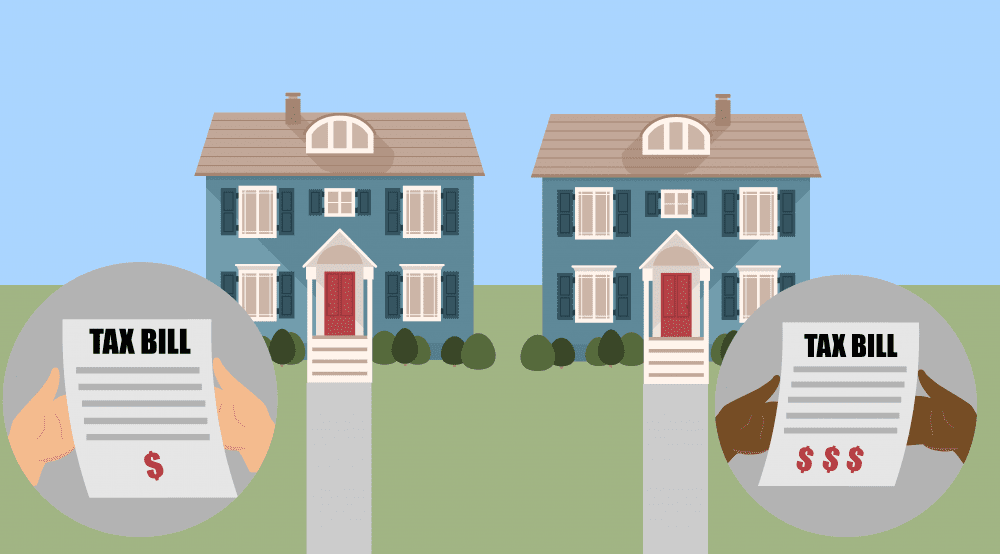

Black people with a college degree have lower homeownership rates than white high school dropouts, Hirtle says. “When you factor in the fact that Black families, because of and on top of the racial wealth gap, are more likely to have to rely on student loans to finance a college education and have to rely on larger amounts of student debt to finance a college education, and then you combine that with income and job discrimination that makes Black families and Black graduates less able to pay off their debt, it really adds up. There’s less money for these folks to be able to . . . access homeownership, put money into retirement, and access other forms of wealth building.”

A 2016 poll found that 48 percent of young people between the ages of 18 and 34 who either own or have plans to own a business say that student loan payments have affected their ability to open shop or expand their business. Additionally, the more student debt someone has, the less likely they are to start a business. For example, someone with an average student loan debt of $30,000 is 11 percent less likely to start a business than a person who graduated debt-free.

The weight of this debt can be mentally and emotionally overwhelming for many graduates. “I used to be one of those people that was like, ‘All right, as soon as I graduate, I’m going to have a five-to-10-year plan, and I’m going to work six bazillion jobs so I’ll be debt free by the time I’m 35.’ No. I don’t think that’s honestly quite possible with the way things are set up here in the United States,” says Emily. “And also, I feel like I shouldn’t work myself to near death, and to not be happy in my day-to-day life because of some debt.”

And then there are defaults, which can have disastrous and long-lasting effects on credit scores and prevent individuals from buying homes and starting businesses altogether. Of the student borrowers who entered college in the 2011-2012 academic year, 32 percent of Black borrowers had defaulted by 2017, compared to just 13 percent of white borrowers. Many of those who defaulted didn’t manage to attain a degree.

To Forgive or Not to Forgive?

Is there a way to address the student debt crisis and the racial wealth gap?

“Broad-based student debt cancellation is one key solution needed to end the student debt crisis,” says Hancock of Generation Progress. “And would also help to address the racial wealth gap since borrowers of color hold disproportionate amounts of student debt.”

However, a few researchers have argued that universal student debt forgiveness may be counterproductive to closing the racial wealth gap.

A 2015 report from Demos examined how universal student debt relief would affect racial equity for young adult households age 25 to 40. Researchers analyzed the effects of various levels of student debt forgiveness: eliminating student debt for those making $25,000 and below, for those making $50,000 and below, and for all income levels. They found that universal student debt forgiveness would actually increase the difference in median wealth between white and Black young adult households by 9 percent, or nearly $3,000. Researchers say this is because white students attend college and seek advanced degrees in greater numbers, so they may benefit more from loan reduction policies that do not have income or financial constraints.

But another study by Brookings notes that even though in some income ranges it does increase the wealth gap, universal debt cancellation still reduces the Black/non-Black wealth gap when measured as a ratio, at every income level.

“We find that the more student debt that is canceled, the greater the effect increasing Black wealth, particularly for households below the wealth median,” the study reads.

The researchers also fight back against the assertion that broad, universal student debt forgiveness would disproportionately benefit white people, noting again that Black people borrow at higher rates because they have less familial wealth to draw upon.

Additionally, forgiveness of loans held by the federal government is different from forgiving all student loans. Nonbank marketplace lenders like Splash Financial and SoFi offer low-credit-risk households the option to refinance their student at lower rates, something that primarily higher-income graduates do. Those interested in SoFi’s student loan refinancing must have a minimum credit score of 650, graduate from an accredited university or graduate program, be gainfully employed within 90 days, have a sufficient monthly cash flow, and have a financial history “that demonstrates financial responsibility.” It’s therefore not surprising that the average income of SoFi’s approved borrowers is more than $100,000. According to the Congressional Budget Office, this means that many of those who can refinance often do, leaving the federal government holding the highest-risk loans held by low-income and low-wealth households. Full forgiveness of the student debt held by the federal government would therefore be of disproportionate help to households with low or no amounts of wealth, especially households of color.

There’s been a recent surge in pressure from both the public and Democrats in Congress for President Joe Biden to act. Sen. Bob Casey (D-Pa.) recently said to The Hill, “The [Biden] administration needs to engage more with Congress on this because I think there’s real concern.” Backers of student debt forgiveness are awaiting a memo from the Department on Education that would clarify Biden’s legal authority to forgive student debt. Biden has already cancelled $12.7 billion in student loans—which is less than 1 percent of the $1.8 trillion of outstanding federal student loan debt—but those cancellations have been through existing programs authorized by Congress, and Biden doesn’t believe that the president has the authority to unilaterally provide wide-scale student loan cancellation without authorization from Congress. However, it has been over eight months since Biden requested that memo, and patience among advocates is wearing thin.

While Biden has extended the pause on federal student loan payments through May 1, student debt forgiveness advocates say that this is not enough. They point to Biden’s campaign promise to forgive at least $10,000 in student loan debt per borrower.

But for borrowers with large amounts of debt, that may be a drop in the bucket. “What the hell is $10,000 going to do on $100,000, or even $50,000 or $60,000 [in debt]?” Vincent says. The delay in action from the Biden administration has him skeptical about their commitment to fulfilling their campaign promises.

“Full administrative debt cancellation is the best policy remedy to the student debt crisis,” Hirtle says. “It would be a fast, easy, and massive step forward toward racial equity that could begin to close the appalling racial wealth gap.”

|

Help keep us strong by becoming a Shelterforce supporter. |

Comments