This article is part of the Under the Lens series

As the housing industry attempts to address the affordability crisis, there has been a tendency for many in the industry to look outside of their own practices, toward the distant horizon for solutions. Modular construction, 3D printing, and the recycling of shipping containers for housing are just a few of the potentially revolutionary technologies that have been promoted as ways to increase affordability.

However, these emerging technologies and approaches have yet to produce compelling, sustained results in terms of increasing the speed of development or construction, or reducing the costs of the homes delivered. In fact, project teams that try to explore the use of these alternatives often incur additional development costs and risks.

What if instead of looking so far afield, we looked internally at our typical design and construction methods? Could we identify ways to modify them to achieve the cost savings we are looking for, while maintaining and perhaps even increasing the quality of the housing we are delivering to our communities? My experience says we can.

Walsh Construction Co. (WALSH) has been building affordable housing for over 60 years throughout the Pacific Northwest. We’ve built more than 55,000 homes. Although we construct a wide variety of building types, multifamily affordable housing is the heart and soul of our enterprise. The majority of WALSH’s clients develop, own, and operate affordable housing: they include nonprofit community development organizations, public housing agencies, and for-profit affordable housing developers.

These clients have experienced tremendous challenges with rapidly escalating construction costs over the past decade. In the recent past, construction costs in the Pacific Northwest were often around $100,000 per unit. Now, the average hard construction cost per unit is well over $200,000, and it is not unusual to have total development costs per unit exceeding $300,000. Given the limited funding available to produce affordable housing, many in our communities are finding it impossible to meet the cost of housing.

WALSH has experimented proactively with innovative technologies and methods—including modular construction, mass timber, light gauge steel, insulated concrete forms, and structural insulated panels—in a concerted effort to see if these alternatives could produce fundamental improvements in either the cost, speed, or quality of construction. We have consistently found that traditional wood-based construction (or wood/concrete hybrids for taller, mid-rise buildings), built primarily at the site, remains the most economical, highest value construction type for producing high-quality affordable housing.

So how can costs be reduced? Many typical design and construction processes are full of inefficiencies and waste. We have found that that if those are addressed through a proactive and disciplined approach to cost efficiency, there is significant potential for actual, not just theoretical, cost savings.

WALSH has worked with several project teams to develop a methodology called Cost-Efficient Design and Construction (CEDC), which we have utilized on a number of recent projects in the Northwest with consistent, measurable success.

what is cedc?

CEDC posits a set of working principles based largely on product optimization. These include:

- a greater degree of standardization of the basic elements and components that go into affordable housing design—such as unit plans, bathrooms, kitchens, doors, windows, corridors, stairways, and elevators

- optimization of these elements for efficiency, functionality, and constructability, which can notably reduce costs

- improving layout efficiency and material utilization in the building structure, enclosure, mechanical and electrical systems, and interior finishes

- prefabrication of components

- lean construction methods such as target value design and early integration of key trade partners

We have found that a highly focused and disciplined use of these principles and methods can result in 10 to 25 percent cost savings from the nonoptimized designs we typically see. Affordable housing developers will tend to reinvest a significant portion of those savings back into the design, incorporating building performance features and amenities that they otherwise could not afford.

These results can be obtained on all affordable housing projects in the United States, not just those few projects around the country that are pursuing the use of emerging technologies. The principles and methods we’ve been exploring with a number of different developer partners and design teams can reliably deliver more, and better, housing, which our communities desperately need. The CEDC path can be followed in any region, and the positive cost results are widely replicable.

the 80/20 concept

Reducing variation is necessary in production processes to reduce costs while maintaining quality and consistency of a given product. However, it is clear to anyone involved in the industry that every affordable housing project is designed nearly 100 percent from scratch. Unit plans change from project to project, the stairway plans are almost always different, the corridors, the elevator shafts, trash chutes, etc. The floor framing runs parallel to the exterior wall on one project and perpendicular on the next. Mechanical equipment varies as does the approach to routing ductwork and piping. We lack an integrated platform of standardized elements, and a coordinated method for assembly. Some of this is due to programmatic or regulatory necessity, but much of it is owing to complacency and a lack of discipline. This tendency to always build projects that are prototypes is a major factor contributing to rapidly increasing costs.

Of the elements that constitute an affordable housing design, 80 percent are—or could be—the same or highly similar. These are elements that for the most part are hidden or buried behind other elements, such as structure, insulation, mechanical and electrical systems, drywall, firestopping, and acoustic detailing. Standardizing and optimizing the design of those elements brings costs down significantly through reduced material use, improved constructability and productivity, and, more generally, a reduction in complexity and uncertainty for the trades involved.

The achieved savings can then be used for the inclusion of more of those elements that strongly contribute to architectural quality and building performance: the other 20 percent. This covers the form, articulation, and exterior expression of the building; the cladding materials or interior finishes; daylighting and natural ventilation, and amenities such as balconies or roof decks—the custom elements that allow for adapting the building to its unique site and program while providing individuality and character.

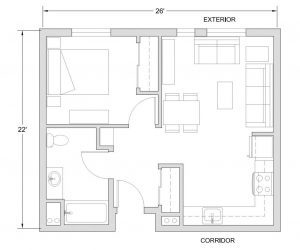

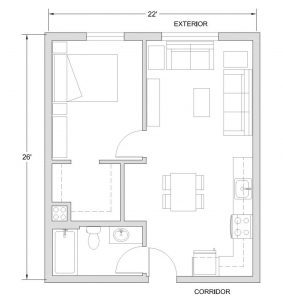

unit design

The approach to unit layout, unit modularity, and structural concepts provides several good examples of the optimization process at work in CEDC. The plans must be large enough to accommodate all the spaces that go with a particular unit type, such that they are functional and livable. Within those parameters, unit plans that are narrower and deeper provide more efficient building blocks than wider, shallower units of the same size. Narrower units require less exterior wall enclosure and less corridor area than the wider units. Exterior wall is expensive, and reducing it also provides benefits in terms of energy performance and long-term maintenance requirements. Corridors are not as expensive, yet they mostly function simply as a means to access the apartments, and reducing their area is typically cost efficient.

A typical one-bedroom unit is 24–26 feet wide. A 22-foot wide one-bedroom unit plan will result in 8 to 15 percent reductions of exterior wall and corridor. Lowering 9-foot ceilings to 8-foot ceilings can reduce the cost of exterior wall construction by more than 25 percent.

In urban infill projects, where site configurations are often tight, optimized unit plans can also allow developers to build 10 to 20 percent more units in the same space.

A few caveats are in order here: There is no question that larger, wider units are more desirable. We are striving to find a balance between functionality, livability, and efficiency. And this notion of narrower aspect ratio can be taken too far. One example is the so-called “Urban One Bedroom” unit, where the width has been reduced to 16-18 feet and the bedroom is placed in or near the center of the unit plan, away from the exterior wall. Access to views, daylight, and natural ventilation is severely restricted for residents with this type of unit layout and we do not recommend such a solution. All living areas and bedrooms should be located along exterior walls, with operable windows.

CEDC also reduces building-material waste by making standard unit elements correspond to the standard dimensions of many building materials, via a 2-foot grid. There are other ways to approach spacing of stud and joists and attaching of the floors that similarly reduce waste, known as advanced framing and modified platform framing. Together, these can reduce the amount of wood framing materials by over 25 percent, which is particularly cost efficient given the current cost of lumber.

Similarly, how the units go together matters. They should be stacked, and ideally arranged back to back to make for the most efficient framing, plumbing, and wiring.

prefabrication

Prefabrication of housing elements and components—combined with factory-based automation—offers great potential to reduce costs, shorten schedules, and improve quality. Just as important is an increase in prefabrication and off-siting of certain parts of the construction process that has the potential to address the acute labor shortage that is currently impacting the construction industry.

Project teams using the CEDC approach should investigate all opportunities to utilize prefabrication wherever it can add value to the project. Components such as windows and cabinets that traditionally were site-built are now almost exclusively prefabricated. The same is true for roof and floor trusses.

In affordable housing, the primary opportunities to leverage additional prefabrication are currently found in structural components such as wall and floor panels. Other opportunities include the piping, ductwork, wiring, and equipment associated with individual units, as well as the potential to use prefab bathroom pods or kitchens. Designers should be mindful to design housing elements to facilitate efficient and cost-effective prefabrication at the factory and installation at the site, following the principles of Design for Manufacture and Assembly. A greater degree of standardization in the design of elements and components could facilitate increased use of prefabrication in the future, as this will reduce complexities and increase the economies of scale in the product manufacturing and associated automation processes.

life cycle cost savings

The disciplined approach to building layout in CEDC generally results in reduced surface area (of floors, walls, and ceilings) and reduced building volume on a per-unit or per-resident basis, compared to typical designs. These reductions yield savings on construction costs, but they also have the potential to bring down operating and long-term costs for building owners. Reducing the area and volume in the building that must be lit, heated, cooled, and ventilated, is likely to yield incremental operational cost savings, reduced regular ongoing cleaning/maintenance costs, and reduced repair or replacement costs over time.

core cedc strategies

Here’s a quick summary of the top CEDC strategies we’ve discussed so far.

- Efficient building plans (net to gross area >80%)

- Efficient dwelling unit plans (narrow “aspect ratio”)

- Building/unit layout on 2-foot module

- Optimize structure/framing

- Floor-to-floor heights match drywall sizes (increments of 48”, 54”, & 96”)

- Stack the units

- Compact plumbing layouts (“back to back” is most ideal)

“Disciplined” approach to windows

There are more pieces to it, from big decisions, like selecting for “unencumbered” sites and avoiding the need for steel through smarter design, to smaller ones like avoiding cantilevers (in wood framing). But everything comes back to the overarching goals of keeping design simple, compact, standardized, and efficient.

cedc in action

In 2015, after publishing a paper called “The Cost of Affordable Housing Development in Oregon,” Meyer Memorial Trust (MMT) issued an RFP soliciting grant proposals to investigate the use of innovative technologies and methods to reduce construction and total development costs. WALSH worked with three of the teams that received these Innovation Grants; two of the teams explored the viability of CEDC principles and methods.

REACH Community Development Corporation initiated the Wy’East Plaza project in 2017 with the intent to use the CEDC approach. REACH set an aggressive goal to deliver housing at Wy’East at 30 percent lower than the total development cost limits established by Oregon Housing and Community Services, the state housing agency. Working with WALSH and a design team led by Ankrom Moisan Architects, REACH exceeded that goal, completing the 175-unit project in 2020 at 39 percent below the TDC limits. I have kept a spreadsheet of costs of publicly subsidized housing in the Portland area for the past five years or so, based on publicly available data. The hard construction cost for Wy’East—$19.4 million ($111,359/unit; $194/sf)—was dramatically below costs seen on other publicly-subsidized projects in the Portland region during the same timeframe, which ranged from $148,000 to $310,000 per unit.

Northwest Housing Alternatives (NHA) also received the MMT grant and used the CEDC approach on two consecutive projects in the Portland area, producing similar results. NHA, working with WALSH and a design team led by MWA Architects, completed the Buri Building, a 159-unit moderate-income housing project in Portland’s Gateway district, in 2020 at a hard construction cost of $19.5 million ($122,833/unit; $213/sf). The cost reduction achieved here is particularly notable given the need for the project to go through Portland’s rigorous design commission review process and to carry significant right-of-way dedications and public street and bikeway improvements.

In Seattle, beginning in 2017, Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) engaged a design team lead by Runberg Architecture Group, as well as WALSH, to develop plans for a site adjacent to Othello Park in the city’s Rainier Valley district. Due to unrelenting cost escalation that was hitting the Seattle region particularly hard at the time, early conceptual designs for the project were estimated to cost well over the target budget that LIHI had established. Funding could not be obtained for the project at the estimated cost, so it was shelved for a time, as happened with many other projects in the region. The team reconvened in late 2018 to take another go at the project, using a CEDC-informed approach. LIHI, WALSH, Runberg, and key subcontractors standardized the proposed unit designs and optimized the building layout and systems design to achieve a target budget reduction of approximately $2 million. Approximately half of that resulted from the redesign and half through collaboration with the framing and plumbing subcontractors, who provided pivotal cost-efficiency suggestions for their particular trades.

Initially, George Fleming Place, as the project is now known, was to be composed of 93 apartments in a six-story building. After implementing the CEDC approach, the project transformed into a seven-story, 106-unit building with a 20 percent reduction in hard construction cost, from $266,000/unit to $212,500/unit. In part due to the enhanced cost efficiency, the project received the needed funding commitments and construction began shortly thereafter, with completion in September 2021. Using the savings, LIHI was able to add back valuable amenities such as a large photovoltaic array that helps power the electrical system in the common areas and a sizable roof deck offering accessory living space to all residents and spectacular views of Lake Washington, the Cascade Range, and Mt. Rainier.

quality

After all this discussion of cost reduction, it is important to underscore one key concern—the question of quality. These cost efficiency ideas are not mutually exclusive with housing quality and design quality. Rather, they are placing a priority on avoiding design moves that tend to add considerable additional first cost without adding commensurate functional or practical value for the short or long term. It is probably accurate to say that many design moves are undertaken primarily if not completely for aesthetic reasons, and in the context of many budget-challenged affordable housing projects those motivations need to be recognized and judged accordingly by project teams as they evaluate the relative merit of various elements.

“One of the biggest challenges in developing new affordable housing is escalating construction costs,” says Dee Walsh, chief operating officer of Mercy Housing (no connection to WALSH Construction). CEDC, she says, “can help us achieve cost containment without sacrificing quality. At Mercy, we’ve built three communities using modular construction with mixed results. Building smarter, rather than differently, is an approach that is accessible to everyone. We’ve used this approach on projects in the Northwest with good results, and plan to expand this approach to other parts of the country.”

The underlying premise of CEDC is that if project teams make the appropriate strategic decisions in terms of those larger-scale measures, we will discover we have more resources available to incorporate the features and measures that truly enhance building quality and durability. At Wy’East Plaza, the project team was able to not only get costs down close to $100,000 per unit, but do so with no net reduction in quality from our typical projects. Furthermore, we were able to show our client a path to meeting the Passive House performance standard for less than a 5 percent cost premium. At the Buri Building, with deft leadership by our design colleagues, the project team was able to show that the CEDC approach can be adapted with skillful architectural effect to satisfy even the most robust requirements of a local jurisdiction’s design review process and produce a very fine-looking building.

Quality is essential to our vision of what CEDC can accomplish, for those who develop affordable housing as well as the people and communities we serve.

Editor’s Note: For more about construction cost savings, check out Shelterforce’s Under the Lens series: Building Differently.

Good article, Mike. I’ve bookmarked it and forwarded it to colleagues in the housing industry in Oregon.

A lot of detail in this article thanks for all the hard work. Affordable housing is important for the community wish everyone took it as serious as you. Good work Sir.