This article is part of the Under the Lens series

The Community Builders has used modular construction—a process in which the primary structures of a building are built in a factory offsite, then transported to the site for assembly—on a couple projects, including Cottage Place Gardens in Yonkers, New York. Photo courtesy of The Community Builders

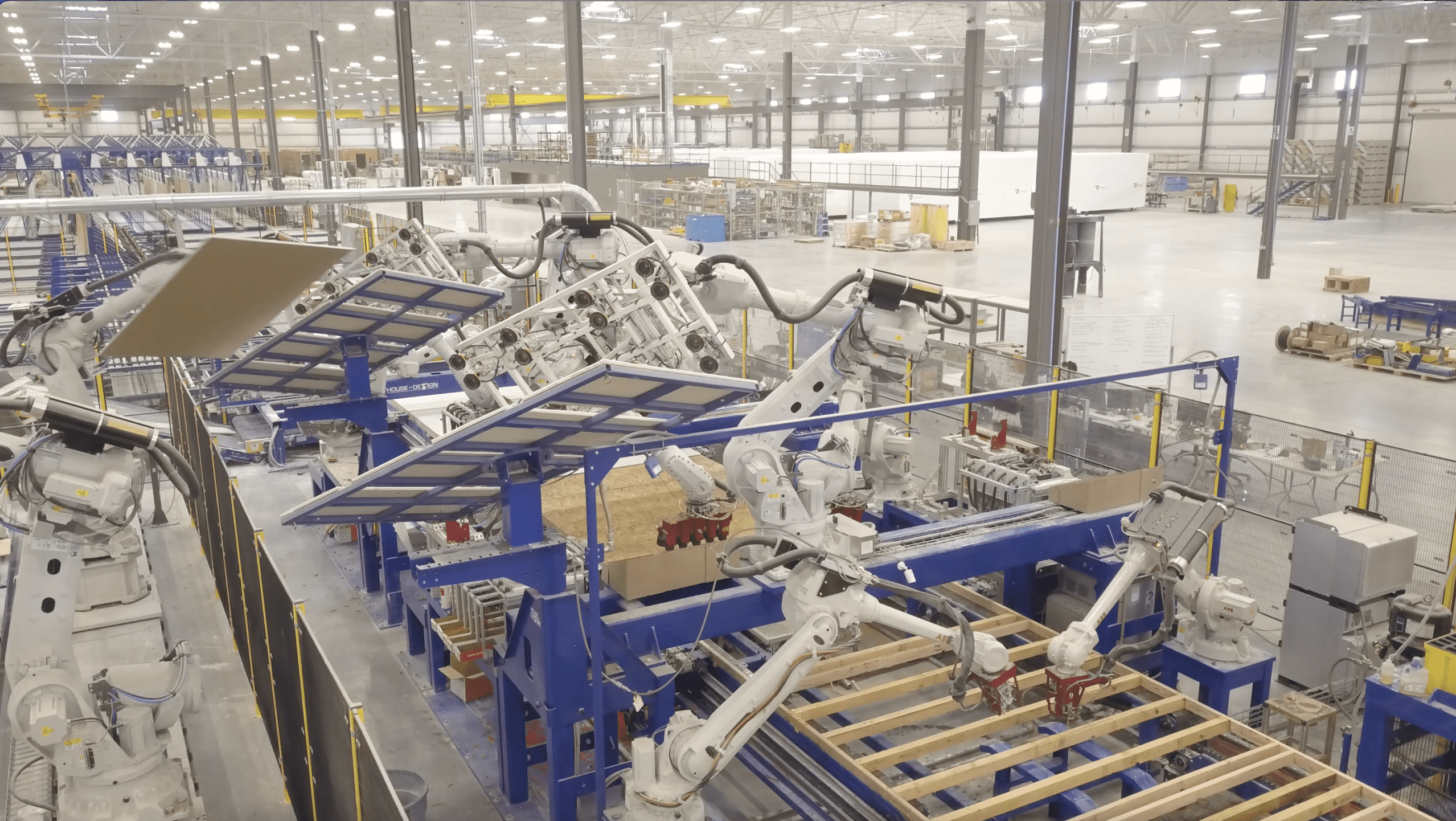

In 2018, The Community Builders, one of the largest nonprofit developers in the United States, worked with the city of Yonkers, New York, to build 70 affordable-housing units on one of the city’s oldest public-housing sites. To carry out the $27 million project, the developer opted to use modular construction, a process in which the primary structures of a building are built in a factory offsite, then transported to the site for assembly. The decision was made “for all the reasons everybody chooses modular,” says Jeff Heisler, vice president of design and construction services for The Community Builders.

|

Building Differently This is the first in a series of articles about alternative construction methods and their use in the affordable housing world. Missed the other installments? We’ve got you covered: |

“It was a faster construction schedule, theoretically less cost—those types of things,” Heisler says.

The Community Builders had used modular construction before for a project on Martha’s Vineyard, which, because of its climate, has a short construction season. That made the appeal of modular, with its speedier onsite building timeline, even greater. The group hoped its experience with the Yonkers project would “get us on the other side of modular,” Heisler says, and make it a viable option for more of its typical developments.

But it didn’t quite work out that way. For one thing, an unpredicted rainstorm came through at the wrong moment and soaked six of the 70 units while they were exposed to the elements, meaning they had to be replaced entirely. For another, the group had to spend extra time with city inspectors to help them understand the process, going as far as ripping out pieces of prefabricated panels so the inspectors could look at the wiring.

“The time that we saved in construction, we lost in permitting to get the regulators familiar with the product,” Heisler says.

In the end, the cost was about the same as the group’s typical project for the area—around $385,000 per unit.

Over the last few years, the cost of construction has continued to rise even as a nationwide shortage of affordable housing has ballooned into a widely acknowledged crisis. Specifically for affordable housing, complicated financing structures and additional regulations can make the development process even costlier and more time-consuming than market-rate projects. In expensive markets with high land costs, the process can be astronomically expensive. A typical affordable-housing unit in California cost more than $425,000 to build by 2016, according to the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley. In San Francisco, the cost exceeds $730,000 for every below-market-rate unit, according to the Bay Area Council Economic Institute.

In the face of higher rents and less available housing, advocates, funders, and politicians have made increasingly urgent calls to reduce the costs of building new, in some cases by using alternate construction methods that could reduce the time, material, and labor costs of development. Repurposed shipping containers, panelized construction, offsite manufacturing of modular components, and, most recently, 3D printing have all been held up as potential solutions to the country’s affordable-housing crisis.

But despite a healthy amount of experimentation, in some cases going back decades (the Modular Building Institute places the origins of prefab building in the U.S. as far back as 1670), new construction technologies that promise to lower costs have yet to be adopted by the housing industry on a wide scale. And community developers in diverse markets say that such methods aren’t yet a viable way to reduce the cost of construction for most typical projects.

“There’s not a great, coordinated system for taking stuff from ideas to scale,” says Jenny Schuetz, a senior fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution who has studied the costs of housing development. “Some of this is happening in the industry—small-scale efforts to identify things that are promising and hold them up. But that stuff doesn’t disseminate that easily.”

There are a few key reasons why modular construction has yet to become an industry standard. Logistically, prefabrication works best and most efficiently when multiple units can be manufactured to a single standard. But development sites are often cramped and irregular in urban areas where housing demand is high. Many single-family infill sites, commonly used for affordable housing, have little staging room to store large parts prior to assembly. A scarcity of manufacturers that build prefabricated units also means expensive long-distance transport for projects in many areas. In addition, local zoning and building codes don’t always allow for modular homes to be built by right. And—a few high-profile examples notwithstanding—using 3D printers to manufacture homes onsite is even further away from widespread adoption.

“Everything comes down to the supply chain,” says Brennan Crawford, executive director of Community Housing of Wyandotte County in Kansas City, Kansas. “An architect can design something that should theoretically come in at $110 a square foot … but that’s all B.S.” In reality, Crawford says, most community builders don’t have relationships with nearby modular manufacturers and experienced contractors that could help them achieve those savings.

Still, some experimentation with modular construction for affordable housing is promising. In a report published earlier this year, Nathaniel Decker, a postdoctoral scholar at the Terner Center analyzed the development of a 145-unit permanent supportive housing project at 833 Bryant St. in San Francisco. The project, built by Mercy Housing through a partnership with the philanthropic organization Tipping Point and the San Francisco Housing Accelerator Fund, has used offsite manufacturing to fabricate modular units and have them assembled onsite as part of a broader strategy to reduce construction costs. In addition to modular construction, the report found, the project has benefited from unrestricted capital without the burdensome terms of most tax credit funding or other government subsidies, along with an expedited permitting process. Overall, the report found that the project was on pace for completion 30 percent faster and for about 25 percent less cost per unit than similar projects in the Bay Area. But the report emphasized that 833 Bryant is “an atypical project,” and its significant cost savings result from the combined strategies of unique funding, fast permitting, and offsite construction. If the project had just used modular construction alone without the other strategies, the cost savings likely would have been much less significant, Decker says.

‘[The idea that] suddenly, just because of technological changes in how homes are built, homes will become affordable, I think that’s an unreasonable expectation …’

“I do think there is real potential for this, but I should caution that that alone cannot drive down the costs of building housing,” he says. “[The idea that] suddenly, just because of technological changes in how homes are built, homes will become affordable, I think that’s an unreasonable expectation to have.”

Developers say the best argument for modular construction is that, in theory at least, it can substantially shorten the construction timeline. According to a U.S. Census report, the average single-family home built by a contractor takes nearly nine months to complete. The Modular Building Institute, a nonprofit trade association, claims that modular projects can be completed “30 percent to 50 percent sooner than traditional construction.” That allows builders to save money on onsite labor, and also to lock in costs for materials and contractor pricing earlier in the development process, which can save money as well. It also shortens the time between when a project is financed and when it starts producing returns.

In a 2020 report, the National Association of Home Builders found that construction costs accounted for about 61 percent of the overall development costs for a typical single-family home. Additional research from Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies and NeighborWorks America found that construction accounts for between 50 percent and 70 percent of costs for multifamily projects. Other costs include land acquisition, design services, financing, permitting, and fees. Some advocates have looked to methods like modular and 3D printing as ways to reduce the design and construction share of development costs.

One of the bigger modular builders in the U.S. is IndieDwell, which is based in Idaho but is planning to expand to several markets across the country, including a new factory in Newport News, Virginia. Pete Gombert, co-founder and executive chairman of IndieDwell, says the group looks for efficiencies in the construction process in a number of ways. For one thing, he says, IndieDwell pays the same wage to workers wherever it goes, and only chooses markets where its rates constitute a living wage. Modular tends to be most effective when the site is within 250 miles of the factory, Gombert says; it’s doable within 500 miles, and beyond 1,000 miles, it only works for “super high-cost” housing markets. The most essential ingredient is repeatability, he says: stretching the upfront investment in design and materials across as many units as possible. IndieDwell has gone all in on modular building, but even still, Gombert says, there remain big barriers to making the method an industry standard, especially in financing.

“Ultimately it will be proven that offsite construction is the right way forward in order to be able to reduce and control costs,” Gombert says. “But we’re not there yet.”

Ryan Smith, director of the School of Design and Construction at Washington State University, says the potential of alternate construction methods to lower costs is limited by several factors.

One factor is that the construction industry overall is fractured, with most general contractors being small businesses with few employees. Most of those contractors have little time, resources, or incentive to invest in experimenting with new construction methods, says Smith, who is also a founding partner at MOD X, a consultancy firm for the industrialized construction industry. Smith is an advisory board member for the Ivory Prize, which is awarded for “ambitious, feasible, and scalable solutions to housing affordability.” The group looks for innovations in three areas: land-use policy reform, development financing, and design and construction. Past winners have included Factory OS, the same modular company that fabricated the units for 833 Bryant St. in San Francisco. But Smith says he has been “floored at how little impact” design and construction innovations have had, compared to changes in land-use policy and efforts to make financing easier to access.

Many developers, including community and affordable-housing builders, remain committed to experimentation with new construction practices, and sometimes they can access unique grants and funding opportunities to learn from those practices. The experimentation that many builders are currently doing on small projects may pay off if methods like offsite modular can become common practice at a larger scale. But the industries that support those methods also need to develop alongside demand for new technologies. And so far, many builders say there isn’t enough of a cost savings with alternate construction methods to support using them in most scenarios.

“There’s an expectation that this should bring down costs a lot,” Schuetz says. “And so far that hasn’t really materialized.”

|

|

At the beginning of this year I met with our construction team to look at “alternative building solutions” due to material shortages and delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic and we came up with the same conclusion. We discovered that the alternative building solutions were not less expensive and in some cases were more expensive and because of learning curves with Zoning and permitting these alternative solutions were not viable alternatives.

We also looked at Manufactured Housing that could be assembled on site but the few companies that we looked at for product fell short of quality and in most cases we just as expensive as houses built from the ground up. The other issue we found with “alternative housing solutions” is the interest rates for the end consumer put this product out of the affordable range. So back to the drawing board, we are still researching and hoping we can find viable alternatives so we can produce more quality affordable housing

Hi- I am part of Global Urban Development (GUD) which brings together U.S. and international community development and urban practitioners and researchers. We have a housing group that meets monthly via zoom and are planning a conference in mid-March tied to an exposition in Dubai.

We are looking closely at innovative construction techniques, notably 3-D. I live in Oakland, and one of the leading 3-D firms, Mighty Buildings, is headquartered in Oakland. They use a synthetic stone made from polymer composite with a steel frame. Mighty Buildings is focusing on scale, energy, and affordable in that order.

They have an interesting pilot with a devloper Palari Group in La Quinta, where they will assemble 15 homes and 15 Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) which is becoming a really important affordable housing development strategy in California given the scarcity and cost of affordable housing. These development will have a net-zero energy cost due to solar panels and batteries. Mighty Buildings is going to introduce a 3-D Print build your own home for $349,000.

GUD is tracking a lot of these interesting developments around the U.S. and globe. For those interested in GUD work and upcoming conferences, you should contact Dr. Marc Weiss, Chairman of GUD at [email protected]