This article is part of the Under the Lens series

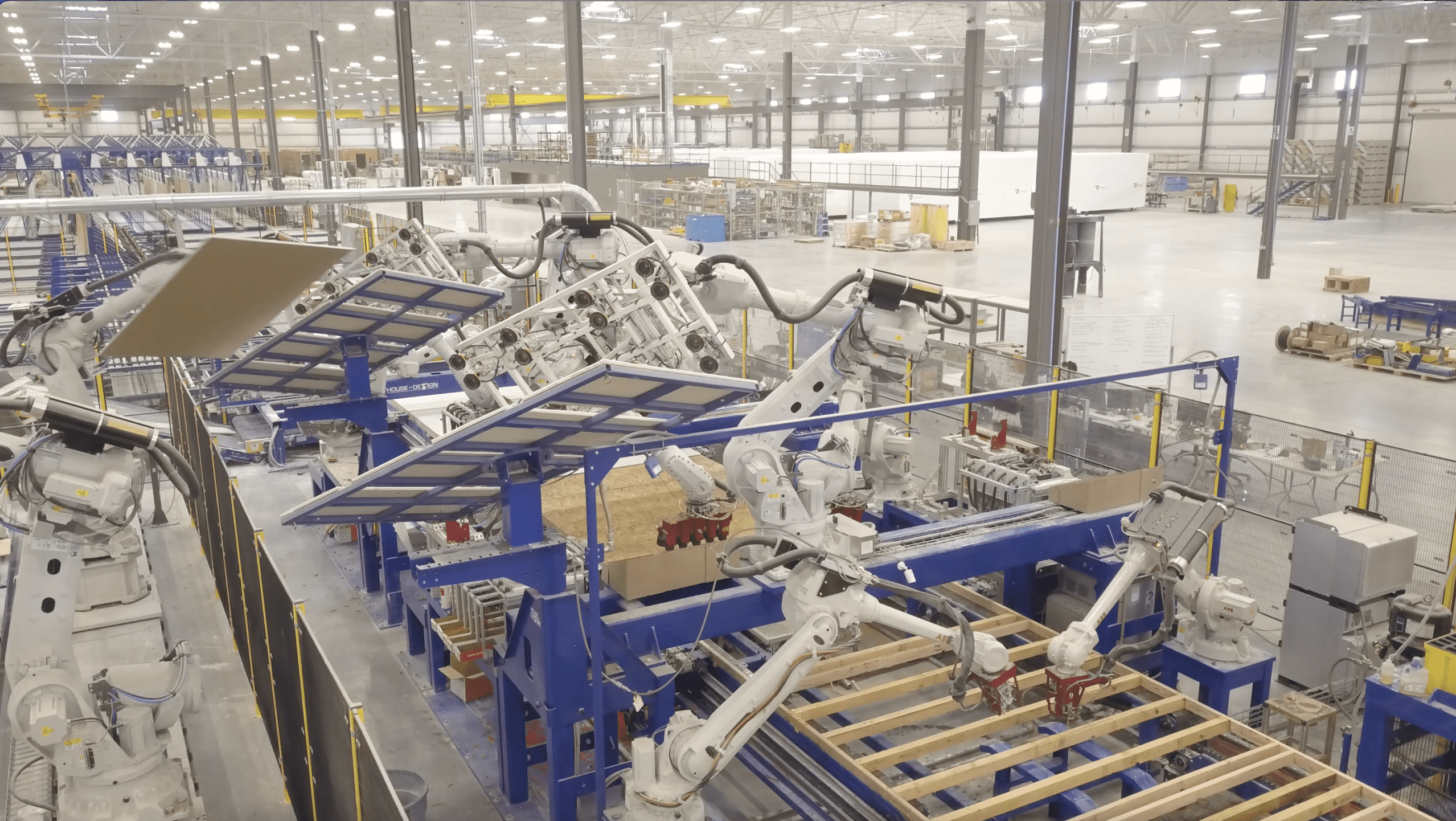

Workers use 3D printed components in house building. Photo courtesy of the Virginia Center for Housing Research

In the last several years, housing developers around the country have been experimenting with innovative construction technologies and processes to reduce the cost of construction. These methods, including things like offsite modular prefabrication, panelization, and 3D printing, have been undertaken in the name of making housing more affordable at a time when nearly half of all American renters are paying more than they can afford for their apartments.

|

This is the third in a series of articles by Jared Brey about alternative construction methods and their use in the affordable housing world. Missed the first two parts? We’ve got you covered: |

But does reducing construction costs just mean paying less money to fewer workers?

The answer, according to some researchers, is a complicated “probably.” And the prospect of short-changing labor has made some nonprofit developers cautious about adopting new methods, especially in the face of unclear results for overall cost savings.

Several years ago, PRG Inc., a nonprofit housing developer in Minneapolis, undertook a modular version of the standard single-family home design they’ve built with traditional construction methods around a dozen times, says Kevin Gulden, a real estate development project manager. The group had been approached by a local contractor that was starting a relationship with a manufacturer, he says, and agreed to modify its home design for a modular development process. Because it was a new process for several parties, there were delays. Prices had to be renegotiated. It cost $13,000 just to transport the modular parts from the factory to the site. And in the end, it cost about the same as a traditional stick-built home, Gulden says. The group will keep modular on the table as an option as the process matures and more manufacturers open. But, Gulden says, “I don’t want to forget what we do for our local labor force when we build our stick-built house.

“We try to work with contractors of color and build their capacity, and I don’t want to leave them out by taking a big chunk of the pie and putting that into a modular build when, in the end, the results are going to be about the same,” he says.

For Lynn McAteer, vice president of planning and evaluations at the Better Housing Coalition in Richmond, Virginia, a 3D-printed house project was a chance to explore the ways that streamlined construction could make housing cheaper. But that isn’t the group’s only concern.

“If you could build five houses with a whole lot less labor, that’s going to save a bunch of money,” McAteer says. “But I don’t think this is kind of ‘the answer,’ because in community development, there are a number of different goals. The first goal, obviously, is to produce housing that is affordable and accessible, but we also have other goals around providing jobs for people.”

Automating certain aspects of the construction process has a fairly clear labor impact, says Jenny Schuetz, a senior fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution. For modular construction and 3D printing, it means fewer onsite hours for construction workers, offset by some new jobs in manufacturing and tech. It’s not clear exactly where the balance is.

“In theory, you could basically be using about the same amount of labor or a comparable number of workers and just shifting the location of where it happens,” Schuetz says. “But probably there’s some reduction in total labor hours and skilled labor.”

Many projects that nonprofit developers undertake are governed by the Davis-Bacon Act, which requires that contractors and subcontractors pay prevailing wages on federally funded projects. For modular projects, says Jeff Heisler, vice president of design and construction services for The Community Builders, “We do have labor savings because we’re buying product instead of carpenter hours.” That can make modular construction more attractive in high-cost labor markets like big cities, he says. And even though the process would reduce the amount of labor required on job sites, Heisler believes that scaling up modular could lead to an overall expansion of the construction industry. Young people, Heisler says, “are not interested in working in the sun and the snow, but they’ll work in a factory.”

Ryan Smith, director and professor at the School of Design and Construction at Washington State University, and a co-founder of the consulting firm MOD-X, says it’s true that a broad switch to modular construction in the housing industry would reduce the amount of contractor labor. But the longer-term impacts could have a balancing effect.

“Does it reduce the number of workers? Yes, it does, because you’re taking those operations into the factory. But not as much as you would think,” Smith says. “If you use the same amount of labor, you’re able to produce more housing units, but in a generation, workers shift from day laborers to technologists—a different kind of work.”

Currently, Smith says, modular accounts for only about 5 percent of all development in the U.S. But there is already a labor shortage in the construction industry, he says, and modular construction could take over a larger share of projects without reducing the demand for labor. One of the reasons why alternative construction practices have been slow to take off is because there are few immediate upsides for the established players in the housing industry, he says.

“The barriers to realizing the industrialization of the construction sector have to do with people, tradition, contracts, reticence to change,” Smith says. “There is, baked into the construction and delivery of housing, a system … that advantages certain groups over other groups. So therefore there’s a lack of desire to change on the part of some stakeholders.”

The considerations for community developers can be layered and contradictory. In St. Paul, Dayton’s Bluff Neighborhood Housing Services opted to use modular construction for a project a few years ago partly because of an existing labor shortage and partly because they expected substantially lower costs by building two-thirds of the new house in a factory with non-union labor, says Jim Erchul, the group’s executive director. The group was hoping to get costs down while still getting a good product. But Erchul says while he has no complaints about the product, the process was unwieldy and didn’t end up being any cheaper than a regular development.

“The quality was very good, and it’s kind of fun swinging a house around with a crane, but there wasn’t any cost savings,” he says.

Beyond that, Erchul says, supporting the local workforce is part of the point.

“For a group like ours who’s interested in neighborhood development, if you’re building something out of town in southern Minnesota, we’re not putting locals to work,” he says. “So that’s a factor that has to be considered in all this.”

In Boston, the nonprofit Preservation of Affordable Housing (POAH) is in talks with a modular manufacturer that’s considering opening up in the area. To make it work, says Cory Mian, POAH’s vice president of real estate development, the manufacturer is trying to build a pipeline of development projects. POAH is considering using modular for a 500-unit project that’s in the works. But even though modular is more appealing in big cities with expensive labor markets, those are also the places where the building trades unions have the most influence. And cutting costs by shipping jobs to a new factory outside the city isn’t exactly a home run.

“Nobody wants to be a jerk; we want to build housing,” Mian says. “There is certainly a sensitivity from local politicians and local constituents about jobs being outsourced.”

POAH hasn’t yet determined whether it will use modular construction for the project.

“Modular technology is worth evaluating as a solution to both cost issues and a way to drive better sustainability,” Mian says. “But it’s not a solve-all.”

Many community developers say they feel responsible for both finding ways to reduce the cost of construction and supporting their local economies with good-paying jobs. To support both at the same time, says Gulden, of PRG Inc., the federal government should follow through on promises to invest billions in housing through the infrastructure plan that’s still being debated in Congress.

“If there’s a way to reduce costs, sure. But that’s not going to solve the whole affordable housing crisis,” Gulden says. “We need massive investment on a large scale.”

|

|

Comments