This article is part of the Under the Lens series

An artist’s rendering of Arts on Broadway in West Palm Beach, Florida, a multifamily development that will be built out of 130 used shipping containers. Rendering courtesy of Stephen Bender

A mile to the north of downtown West Palm Beach lies a neighborhood that is being remade. Northwood Village is an eclectic neighborhood of hipster boutiques, low-rise housing, emergent wine bars, homeless encampments, old motels, and newly arrived construction equipment.

The area is pockmarked with vacant lots and faded remnants of Northwood Village’s light industrial history. But in a thriving city like West Palm Beach, this kind of void doesn’t remain in place for long.

Artists and hipsters began to move in to both the commercial and residential buildings, attracted by the cheap rents. Soon higher-end developers began to follow, and hundreds of new housing units have been built, are in production, or are being planned. The city government is even remaking Currie Park—a green space that overlooks Lake Worth Lagoon and in which people without homes have set up encampments—to attract more residents and tourists.

But one of these housing projects is not like the others.

In the midst of all the activity and attention focused on Northwood Village, there is also a proudly innovative nonprofit housing complex underway. Dubbed Arts on Broadway, this 52-unit multifamily development will be built out of 130 used shipping containers, and many of the units will be targeted toward artists. When completed, it will be the largest shipping container housing project in the country. The idea is help revitalize the community while providing housing that is attainable for current residents. The other idea is to prove that such housing can be constructed for less money by repurposing used shipping containers, a goal that has experienced several false starts along the way but may be finally coming into its own.

Arts on Broadway is the fruit of an alliance between city officials, a New Jersey CDFI, and a large Sunshine State nonprofit developer—all backstopped by a Trump administration Opportunity Zone investment. After multiple delays, it was expected to break ground just off the increasingly bohemian main commercial strip in late 2021.

The project’s champions—New Jersey Community Capital and Florida’s Crisis Housing Solutions—believe that a housing complex composed of used shipping containers shouldn’t be seen as a niche and avant-garde idea. If they can bring Arts on Broadway to the public successfully, perhaps other jurisdictions will consider using port cast-offs to help address the needs of the one-third of Florida residents who spend over half their incomes on housing.

“We’ve been looking for ways that we can do out-of-the-box thinking—or in-the-box thinking in this case—when it comes to alternative construction methods at a lower cost,” said Armando Fana, assistant city manager of West Palm Beach. “There’s been some projects in other parts of the country and other parts of the world using shipping containers that show there’s a cost savings in doing so—and there’s a great need for more affordable housing in Palm Beach County.”

Fana and his colleagues in the West Palm Beach city government have proven exceedingly supportive of the project, donating city-owned land, giving the developers a break on land use regulations, and waiving some permitting fees. Feedback from the zoning board, community organizations, and the city council has proven overwhelmingly positive—there hasn’t been backlash to a slightly eccentric affordability scheme for the city’s artsy-industrial neighborhood.

Many shipping container projects look a bit different from standard construction—often architects want to celebrate the unusual building blocks they are working with. But not everyone likes difference.

“NIMBYism is one of the potential issues with container housing,” says Craig Vanderlaan, executive director of Crisis Housing Solutions, an affordable housing developer founded in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. “If you were to go in a neighborhood that had a certain type of housing, and then you came in with steel homes, it would just look different,” he says, or it would cost more to add cladding to disguise them. But as containers show up more often in market-rate construction, Vanderlaan also thinks that it hasn’t really become a problem. It certainly wasn’t in West Palm Beach. “I probably met with six different neighborhood associations in the Northwood Village area and by the time we were done with the presentation, they were like, ‘Wow, I can’t wait.’”

‘Many workers … travel sometimes 30 to 45 minutes each day to live in an affordable community. Wouldn’t it be great if they could walk to work?’

The project will be affordable to people making from 60 to 100 percent of area median income (AMI). Fifty-one percent of the units will be set aside for those on the lower end of that spectrum—60– 80 percent AMI—and the 2-acre site will be laced through with public space. The project includes 12 loft-style units with higher ceilings, designed to be studio-storefronts for artists, and about 20 micro studio-retail spaces line the ground floor facing the main drag on Broadway.

Vanderlaan says he wanted to build housing for the kind of people who already live and work in the area.

“We felt that artists would love the project due to its innovation and unique building material, but it’s much more than about artists,” says Vanderlaan. “Many workers in local restaurants, shops and the area hospital travel sometimes 30 to 45 minutes each day to live in an affordable community. Wouldn’t it be great if they could walk to work?”

Shipping Containers: Theory

Modern shipping containers were only invented in the 1950s, and truly blossomed with the astronomical growth in global trade since the 1970s. Today, they make roughly 200 million trips around the world annually on ships that can hold thousands of 20- to 40-foot-long containers.

With hundreds of thousands of shipping containers added to the market each year, an obvious question arose: What to do with all the oblong steel boxes that are nearing retirement? The sudden profusion of these gargantuan, 4-ton contraptions piqued imaginations in the architecture and urban planning worlds.

According to one 2017 account, the United Nations was pitched on the idea of using container housing as emergency shelters in the early 2000s. The idea was shot down for both practical and optical concerns. Why should refugees, with little choice over their accommodations, be among the first to try out a new form of recycled housing?

But proponents of container housing urge skeptics to think beyond nightmares of life in cramped and stuffy boxes. A single container would be a tight fit, but in West Palm Beach’s Arts on Broadway project, and most other container home schemes, the idea is to fuse multiple units together.

“When you first think about containers, you think of narrow boxes, of tiny homes, but you can open them up and you reinforce them,” says Stephen Bender, a consulting architect on the West Palm Beach project. “That’s what we’ve seen in London and the Netherlands.”

Containers have been converted into housing in many Western European nations. Maritime countries like the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Denmark have all taken advantage of the detritus of global trade that piles up in their ports. But in the United States, only a handful of units have been popping up, in places like Washington, D.C., and Seattle, Washington.

“People are finally acknowledging that the construction industry is one of the least forward thinking and [most] change-averse industries in America,” says Bender, who serves as acting program director of the Orlando School of Architecture’s CityLab. “And that’s not the same in Europe. There it’s been going on for decades, and it’s readily accepted.”

Environmentally, the appeal of reusing the containers is obvious. Most of these products are made of steel and other resilient recycled materials, then shipped to markets around the world. After a container has neared the end of its lifespan, however, it tends to just sit around in ports, rusting, and eventually ends up as scrap.

Repurposing these heavy-duty, wind-resistant structures compares favorably to the carbon footprints of other common building materials. Reused shipping containers have a far smaller carbon footprint than concrete, a material whose manufacture is responsible for a devastatingly high amount of emissions. (A recent Guardian article found that if the concrete industry were a country, it would be the third largest emitter of carbon dioxide on earth, after only China and the United States.)

But Bender says that the environmental advantages of reusing shipping containers can even be favorably compared to wood construction. He recently completed a yet-to-be-published study of the global warming impact of construction using containers versus stick-built homes. It found that the material is at its environmentally friendly peak after the receptacles have been reused.

Bender says that utilizing a container that has only made one or two trips is not any more environmentally sustainable than a conventional wood-frame building. It takes a lot of (usually carbon-fueled) energy to manufacture a reinforced steel box that can resist heavy loads and strong winds. All that reinforced metal is the reason they are far more durable than wood for home construction, but to offset the carbon imprint of that process the container must first be repeatedly used for its original purpose.

“We lean toward reusing them when they are at least at the end of [the] life cycle from a shipping industry point of view,” says Bender. “We catch them when they are still cargo-worthy units, but they aren’t the prettiest ones. Their carbon footprint has already been mitigated and in that context we dramatically outperform wood frame construction.”

Proponents of reused shipping container housing also argue that it enjoys serious cost-saving advantages over other building materials. At the end of their useful lifespans, these structures don’t cost a great deal to obtain. The nonprofits behind the Florida project estimate that they will save massively on materials as a result.

Jeff Crum is the chief operating officer of New Jersey Community Capital, and he says that the potential cost savings for affordable developers could safeguard government coffers.

He estimates that under normal circumstances the number of units being provided in the $9 million West Palm Beach development, reaching the modest income threshold they are targeting, would require most of the financing to come through public subsidy.

With the savings from using the containers as literal building blocks, they could reach the same housing affordability with $500,000 in subsidy instead of $7.5 million.

Despite the current hot housing market, Florida is in some ways ideal for this experiment. Because Florida is frequently buffeted by hurricanes, its building codes are some of America’s toughest to meet. The wind zone in West Palm Beach is 140 miles per hour—that’s the amount of wind pressure any construction must withstand, and it’s even higher in other areas on the peninsula where container housing is being considered. All the cladding and other components on the outside of the building that could be exposed to wind and flying debris must meet rigorous requirements.

According to Crum and Bender, shipping containers inherently have the durability to pass—and far exceed—the Florida building code’s impact and wind load tests.

“A shipping container has inside of it a steel frame that’s been made to withstand being stacked 15 to 20 units high [in] huge winds and rainstorms on ships,” said Crum. “It’s a really resilient system.”

An aerial view of West Palm Beach. Photo by Flickr user Kim Seng, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Groundwork

Financing shipping container construction can be a challenge. If containers are to be used for single-family housing, there are structural financial impediments. Homeowners insurance companies and home lending institutions are not known for their embrace of the new. It is difficult to obtain conventional mortgage financing when recycled containers are the construction type. To make things more difficult, when banks make a loan, they usually then package the mortgage up with others of its ilk and sell the bundles as securities. But that can only be done with projects of a similar construction type, and there simply aren’t enough container houses being manufactured in America to do that.

When it comes to multifamily housing, the financing is even more complex. In this field, a shipping container project needs a lender who is willing to be educated or who is actively looking for ways to innovate around housing affordability. On the development side, a trusted team is needed that can make lenders comfortable.

It was having that rare combination of factors that allowed the West Palm Beach project to get off the ground.

The West Palm Beach project’s origins lie in 2017, when New Jersey Community Capital (NJCC) applied for JPMorganChase’s ProNeighborhoods grant with a fellow community development financial institution Florida Community Loan Fund (FCLF). The program gives funding for partnerships between community development financial institutions like NJCC and FCLF to aid them with their investments in distressed communities.

In the 2017 round of grants, NJCC and the FCLF won $5 million for a collaborative effort to come up with innovative affordable housing strategies. In their pitch, they focused on the central part of the state—specifically the Orlando metropolitan area—and the southeastern region, where the affordability crunch is particularly acute. But although the ProNeighborhoods grant was tailored for a partnership, it also allowed the two CDFIs to explore separate avenues for “innovations in affordable housing creation.” Though FCLF did approve a line of credit to finance site acquisition for Arts on Broadway, that line of credit was never used, and they have been otherwise uninvolved in the West Palm Beach project.

NJCC began putting together the Arts on Broadway project with frequent Chase collaborator Crisis Housing Solutions, which had already been crafting plans for container housing projects for years.

A feasibility study indicated that the use of shipping containers should reduce material costs. The expectation was about 20 percent savings, which would have amounted to approximately $105,000 per unit at the square footage the project settled on. But it also presented aesthetic and familiarity challenges. Would municipalities and neighborhood groups balk at a concept so far outside the existing norm?

That’s where Crisis Housing Solutions came in, bringing their relationships with local officials and their knowledge of container housing to partner with NJCC’s proficiency with accessing public, private, and nonprofit financing.

“NJCC brings a wealth of knowledge and expertise in the areas of finance and the overall development of affordable multifamily housing. They’ve got the process down pat,” says Vanderlaan. “Local government officials also recognize the value of having NJCC involved. From this experience, I highly recommend that nonprofit developers partner with others outside of their familiar markets.”

Together NJCC and Crisis Housing Solutions met with officials from Orlando and other municipalities in the central and southeastern parts of Florida. But one city was the most enthusiastic by far.

“West Palm Beach approached us,” says NJCC’s Crum. “They were really the most interested in this and saw container housing as a way to solve their challenge of affordable housing.”

The city of West Palm Beach donated five parcels next to two parcels NJCC had acquired at below-market value, allowing the developer to acquire the land for Arts on Broadway at a 50 percent discount. On the acquisition side, the project was off to a good start in terms of cost savings.

In Pursuit of Lower Construction Costs

Cost savings on the construction side were far from automatic, however. The processes—both of creating the units and assembling them—are fairly new, so finding appropriately skilled labor and manufacturing facilities, and figuring out a design that works in practice as well as theory, has been a longer, and costlier, process than expected.

‘Everybody’s kind of trying it, but it’s a little harder than it sounds to actually get that ramped up.’

Because shipping containers aren’t a standard material in the Florida building industry, there aren’t a lot of vendors who can modify or install them. It also proved difficult to find a fabricator to quickly bring together multiple containers into units of a livable size, because the manufacturing infrastructure simply doesn’t exist in the region yet.

“You need a certain amount of volume that you can count on in order to design your manufacturing and production process, as well as your purchasing to get the economics to actually be lower cost,” says Thom Liggett, managing partner of Performance Capital, a contractor with experience in other kinds of prefabricated housing brought in to help with the project.

“Otherwise, they’re much higher costs than traditional building methods,” says Liggett. “Probably the key challenge is having enough demand to deliver the supply into. Nobody’s really done it at any volume in the United States. So everybody’s kind of trying it, but it’s a little harder than it sounds to actually get that ramped up.”

Crisis Housing Solutions is planning to build a factory themselves, but in the meantime, they first tried working with a small outfit called Little River Box Company. They ordered a prototype of three combined containers, which would make a living unit of a little under 1,000 square feet.

But because the field is so untested in the region, Little River Box Company encountered insurmountable difficulties. It was unable to secure the financial backing it needed to ramp up and handle a project of this size. As a result, it was never able to get the capital to hire the dozens of workers needed for the project or to purchase the necessary equipment. Originally NJCC and Crisis Housing Solutions wanted the container prototypes to be finished by late 2019. Instead, they were never able to bring the prototypes from the company online.

Not only was the production not as efficient in a one-off, but the bids coming in from contractors for assembly were unexpectedly high—again, likely because of the unfamiliarity, and the logistical issues.

Crum also attributed some unexpected costs to the booming residential construction market in this corner of Florida, which drove the costs of even traditional labor and materials unexpectedly upward in 2019.

In early 2020, Crum appeared ready to accept a lower discount on costs for this initial project as part of a learning process. “The hope is that this creates a pathway, and then we can start hitting that 20-to-25 percent discount,” he said at the time.

But Michael DeBlasio, director of property acquisitions and operations for Community Asset Preservation Corporation (CAPC), the subsidiary of NJCC that carries out development projects, wasn’t so ready to give up. He ran a “value engineering” exercise with the architect, whom DeBlasio describes as one of the top people working on shipping container designs in the country, and shaved off some costs.

The architect also connected NJCC to Innovar, a company that had used shipping containers in schools, tiny houses, and houseboats. Though they hadn’t done a multifamily project like this, they had a manufacturing space already, which Little River didn’t, and an existing relationship with a general contractor that was big enough to be bondable, which PNC, one of the project’s major lenders, required. “We were on a good path, though the first numbers were a little high,” recalls DeBlasio. “We did more tweaking, things were going in the right direction.” And then in early summer 2020, after being on weekly calls for months, Innovar pulled out of the project.

“It was like a punch in the face,” says DeBlasio. “We were a little bit lost.”

Third try’s the charm? While this was going on, Crisis Housing had found a general contractor who had done single-family container projects before to take over developing the prototype unit. He hadn’t been able to be bondable when the project was started, but his business had grown, and now he was, so they entered discussions with him to become the general contractor for the whole project.

But the first numbers were still too high, not just compared to the initial feasibility study, but even compared to more recent, less ambitious projections. At that point, DeBlasio says, they began to wonder if the issue was also one of design, not just unfamiliarity. They shifted to a design-build approach and had the architect and the new general contractor take a hard look at the design. Having the contractor deeply involved was key. “Someone who actually builds it can see efficiencies,” says DeBlasio. He had them reorganize the plans to make stacking much easier, so that wires and systems can go straight up and down in the walls as in stick-built. As of late August 2020, he said, they’d cut $1 million out, with $600,000 more expected. The new design used 20 fewer containers for the same number of units and maintained the integrity of the street facade. One section of the building will be only two stories, and units were reorganized.

“I feel much better than I have at many stages of this project,” said DeBlasio in August 2020. “Egos are out the window.” It still took several steps. As of mid-September 2020 they had gotten the cost down to $127,000 per unit (from $145,000). To get to their revised goal of $120,000 per unit they eventually had to postpone the inclusion of commercial units to a later phase of the project. (The initial feasibility study had suggested they could get down to around $105,000 for units of the size in the plans.)

The final costs were within half a million of the revised projection, and NJCC was able to raise the difference from a private Opportunity Zone investor.

“Lesson 1 is the projected cost savings have not materialized at all,” said Jeff Crum of CAPC in early 2021. The development is being assembled on site, with no offsite or factory work. “It’s all customized work at this point,” says Crum. “Nothing standardized or replicable. Without scale it’s not cost effective.”

Arts on Broadway is moving forward. As of September 2021 the organizations have found two general contractors with interest and experience to assemble the project, leased a nearby lot to use for assembly while foundation work on the site is happening, and closed on the financing. “It’s working out so well. A year ago, we weren’t so sure,” says Vanderlaan. “But it’s all coming together.”

Because construction prices have been rising in Florida over the time that this project has been underway, before giving a final assessment, Crum would like to get an apples-to-apples comparison of a similar project built during the same time frame. “We’re comparing to 5-year-old numbers, which isn’t necessarily fair,” he notes. “We need a postmortem.”

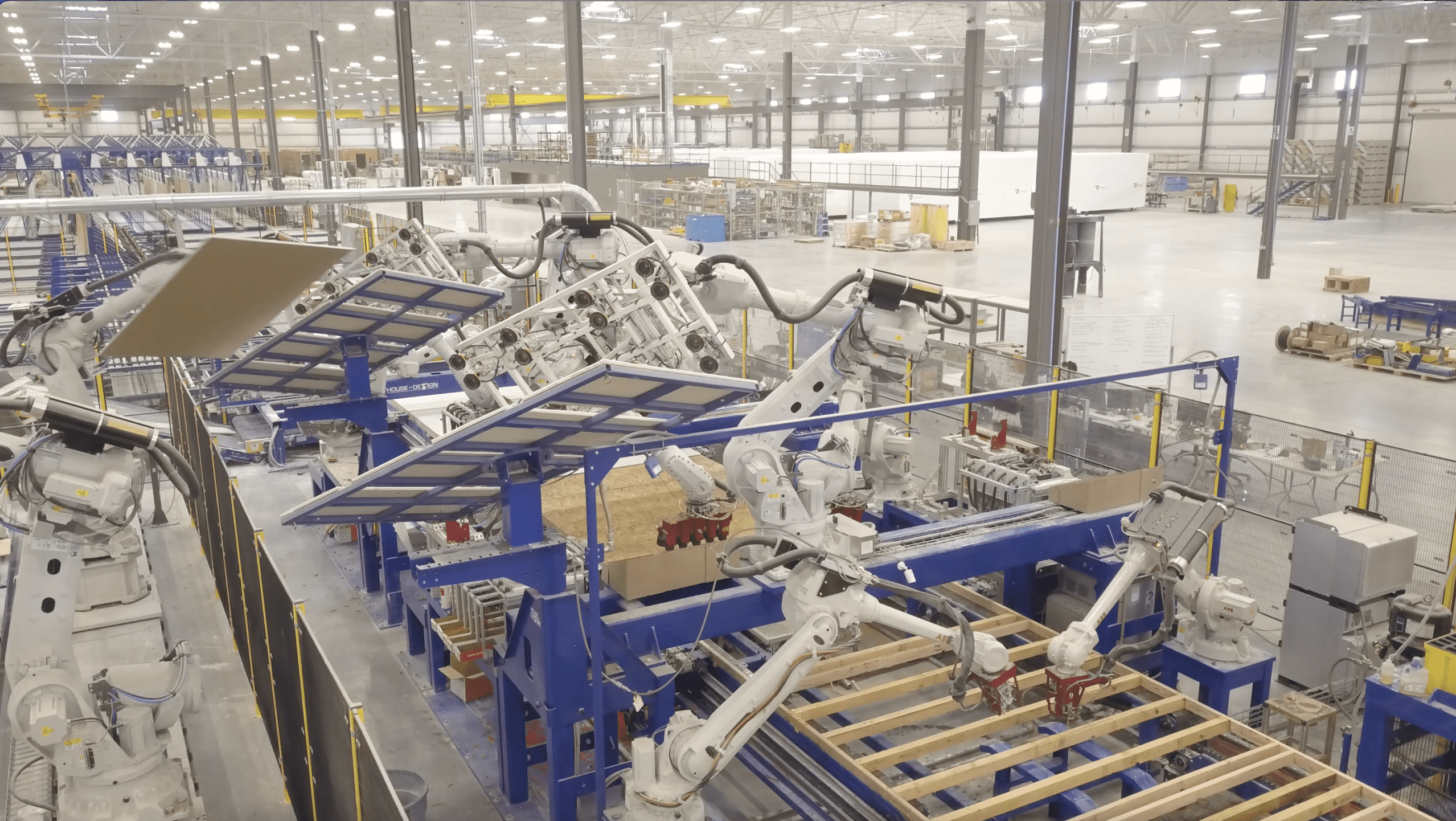

And, of course, the ultimate goal would be to use the lessons from this development to move into projects that are standardized and replicable, achieving that necessary scale. The lessons from Arts on Broadway are feeding into the plans for a factory in Jacksonville that will enable research and experimentation on doing shipping container and other modular construction on assembly lines. That might get to the efficiency and standardization needed to bring costs down.

Next Steps for Shipping Container Housing

Beyond West Palm Beach, both NJCC and Crisis Housing Solutions are bullish on the future of shipping container housing in Florida.

Vanderlaan’s organization is working on a repurposing facility, which will open in late 2021 in a shipyard in Jacksonville, Florida. When it comes online, Vanderlaan says, it will help dramatically with cost savings.

“They’re taking the containers to the sites and they’re building them right there on site and they’re saving a little bit of money,” says Vanderlaan. “But when you can do this in an assembly line, now you’re saving costs in so many different ways. You get greater efficiency, greater control over your staff, greater oversight. You never have a rainy day.”

NJCC explored with a central Florida and Panhandle-based group the idea of opening a factory based on the specs of an outfit called IndieDwell. This Idaho-based company has patents on the design of a basic factory to turn containers into living units, with the fabrication process built in, which can be copied and quickly set up elsewhere. Esteban at FCLF had made the connection to IndieDwell, and there was some hope they might provide units for the Palm Beach project, but the standardized design would have had to change too much, so it wasn’t employed for that project.

“IndieDwell has a very specific business model,” says DeBlasio. “You wouldn’t go to them with your design.” Once they complete this project, they hope the design they’ve settled on and the relationships they’ve built will allow them crank out future projects efficiently, as IndieDwell does.

The community development financial institution’s efforts to innovate in affordable housing construction are not limited to the shipping container model. Inspired by the shipping container project, NJCC is also exploring other forms of modular construction that are well fitted to the Florida landscape, working with a company called Next Generation on super-energy-efficient prefabricated homes of steel and spray foam insulation. This approach is being used for residential infill on vacant lots near the Parramore neighborhood, where other ProNeighborhoods investments were also made.

These other forms of modular housing are easier to get off the ground now because there are already factories in place and laborers who know how to work with the materials.

But the shipping container advocates say that in the new climate reality, that isn’t enough. An eye to the carbon footprint and environmental impact of building materials gives an advantage to the containers. And while the Next Generation modular homes are more resistant to wind and debris than standard block-and-stick construction, they aren’t as tough as shipping containers.

For Vanderlaan, that means a great deal. It isn’t as though the future will contain fewer, or tamer, hurricanes. Quite the opposite.

“When the hurricane comes and you lose your roof, you lose your house,” says Vanderlaan, who founded Crisis Housing Solutions in response to housing needs after a hurricane. He advocates for smaller shipping container units for disaster relief as well—unlike the sorts of trailers FEMA currently uses, they can be shipped safely around the world, stored easily, and reused.

“You cannot lose your steel roof in a hurricane,” says Vanderlaan. “People are looking for answers, and when they find out that you’re not living in this little narrow box of steel, and that they have a steel roof too? It’s a tremendous opportunity.”

This article is excerpted from the white paper evaluation of NJCC and FCLF’s ProNeighborhoods grant, forthcoming.

|

|

Comments