This article is part of the Under the Lens series

The Racial Wealth Gap—Moving to Systemic Solutions

In August 2014, Michael Brown, an unarmed 18-year-old Black man, was shot and killed by police in Ferguson, Missouri. Brown’s death caused an uproar about police misconduct in Ferguson and prompted an investigation by the United States Department of Justice in March 2015. That investigation found that the municipal court’s emphasis on revenue generation and its history of racial bias led to the Ferguson Police Department’s aggressive enforcement of municipal code, which compromised public safety, especially for Black residents.

The report highlighted the story of an African American woman who in 2007 was fined $151 for parking illegally. In a little more than three years’ time, the woman, who had experienced homelessness, was charged with seven offenses for failing to appear in court and missing fine payments, each offense then leading to an arrest warrant and additional fees and fines. Over a period of seven years—for the same parking offense—the woman was arrested twice, spent six days in jail, and paid $550 to the court. Despite initially owing a $151 fine and already paying $550, the woman still owed $541 when the Department of Justice report was written.

Nonpayment of fines and fees has serious consequences—damaged credit, loss of a driver’s license and voting rights, incarceration, and other punishments. And because of racially biased overpolicing, Black Americans are more likely to be processed in the criminal justice system and hit with these crippling fees and fines.

“In many places, people are told that if they don’t pay their court debts, they will be arrested and jailed. They forgo basic necessities, borrow money from friends and family, or use tax returns to pay the government and stay out of cages, but their financial situation becomes increasingly precarious,” says Elizabeth Rossi, a senior attorney at Civil Rights Corps, a nonprofit that challenges systemic injustice in the legal system. “This debt trap disproportionately affects Black people and people of color.”

And this, of course, contributes to maintaining the long-standing wealth gap between Black and Brown communities and white communities.

What is Legal System Debt, and Who Benefits?

Photo by Flickr user Brenda Gottsabend, CC BY-NC 2.0

Legal system debt, also known as court debt or legal financial obligations (LFOs), includes fees, fines, court costs, and restitution. It also includes other financial penalties and consequences resulting from being convicted of a crime.

Fines serve as a form of punishment for breaking the law, and they can also serve as a deterrent for future misconduct. Fees, on the other hand, are essentially charges for being processed through the justice system. They can be assessed for any contact with the criminal justice system—booking fees, prosecution fees, incarceration charges, assessments, surcharges, probation fees, parole fees, and public defender fees. Because fees are assessed throughout the justice system from arrest through supervised release, they can total hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of dollars, depending on location and the judge that heard the case. How much court debt is there in the U.S.? The Fines and Fees Justice Center reported $27.6 billion of total national court debt, with Washington, Virginia, California, Oregon, and Iowa having the highest per capita debt in the country.

In places like Alabama, fees and fines serve as an alternative way to fund the state, acting as a “hidden tax,” says Leah Nelson, research director at the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice and the author of Under Pressure: How Fines and Fees Hurt People, Undermine Public Safety, and Drive Alabama’s Racial Wealth Divide.

“Alabama is a very low-tax state, but we still need the state to do various things, including provide public education, maintain roads, and so forth,” says Nelson. “So to fill in the holes left by our bare-bones tax structure, we use legal financial obligations as an alternative tax, which is levied against people found guilty of some crime.

“The short answer to ‘why do people accrue this debt?’ is ‘because Alabama doesn’t take in enough revenue from taxes so it uses fines, fees, and court costs instead.’ And that’s true in other states as well,” says Nelson.

The cycle of legal system debt creates a toxic relationship between the individual and the state, Nelson says: “When we use legal financial obligations as an alternative to tax, we’re basically saying we need people to commit crimes and be found guilty or we won’t be able to fund basic services like schools and roads. That’s a pretty cynical bet.”

Though the revenue generated from fines and fees is intended to fund local governments and public programs, the effort to collect money from people who are struggling to pay is often futile. Punishing people unable to pay by taking away their driver’s licenses and other negative tactics often leaves them unable to work, and therefore even less able to pay.

“People are unable to participate in the economy when the debt is a barrier to working, either because their driver’s license is suspended, or occupational license is suspended because of the money they owe,” says Joanna Weiss, co-founder and co-director of the Fines and Fees Justice Center.

Ultimately, court debt ends up costing states more than it benefits them. For example, one county in New Mexico spends $1.17 to collect every $1 of revenue it raises from fees and fines, according to The Brennan Center for Justice. It can also cost 115 percent of the amount that would be collected to jail someone who cannot pay their court debt.

“It is very difficult and expensive to try to collect debt from people who do not have money, so, often, only a very small amount of what is assessed is actually collected,” says Weiss. California serves as an example of this: in the 2017-2018 fiscal year, California collected $166.1 million of court debt, with $10.3 billion of debt still outstanding, according to the Fines and Fees Justice Center, meaning only about 1.6 percent of total court debt was collected.

Overpolicing and the Racial Wealth Gap

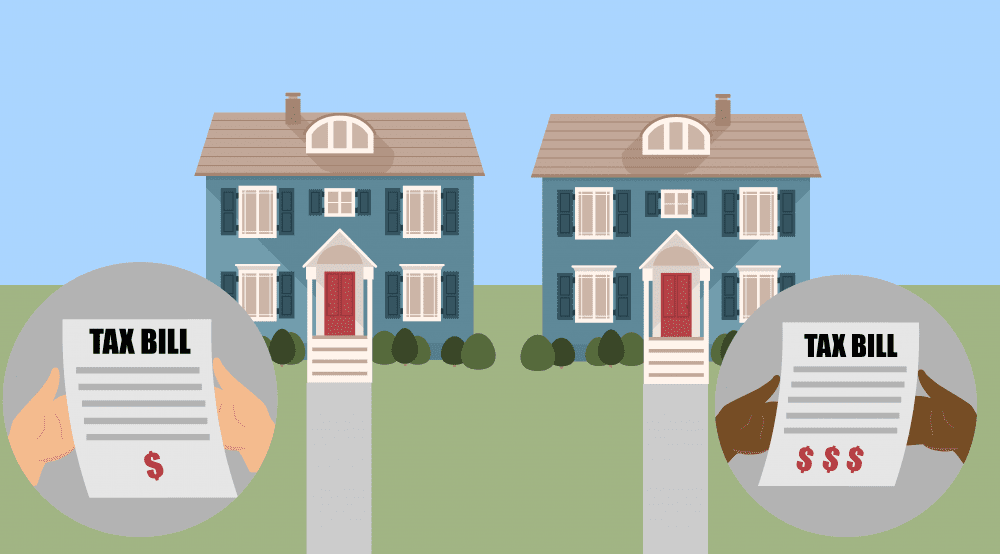

According to a 2019 survey by the Pew Research Center, Black adults were about five times more likely than whites to say they’ve been stopped by police because of their race or ethnicity. Further, Black Americans are more likely than their Hispanic or white counterparts to be in prison. In 2018, the Black imprisonment rate was five times the rate among whites and nearly twice the rate among Hispanics.

“Because of overpolicing of communities of color, compounding with racial disproportionalities throughout the criminal legal system, people of color are more likely to be stopped, charged, prosecuted, and punished. Thus fines and fees fall even more disproportionately on people of color,” says Weiss.

The burden of court debt not only affects an individual, it has the potential to affect their family for generations. According to a PolicyLink report, Ending the Debt Trap: Strategies to Stop the Abuse of Court-Imposed Fines and Fees, more than 60 percent of incarcerated individuals relied on family members to help them make payments, and over 20 percent took out loans, often high-cost payday or title loans.

“Because fines and fees are assessed very heavily on people who cannot afford to pay them, family and friends often come up with the money to keep their loved ones out of jail. Fines and fees extract wealth not only from a person accused or convicted of a violation, but from entire communities, disproportionately Black and Brown communities,” says Weiss.

Alabama Appleseed’s Under Pressure report found that middle-aged Black women were more likely than any other group to pay off a family member’s debt. According to the report, “While others their age were saving money for retirement, helping their children with college or other expenses, paying down mortgages, or taking vacations, these African American women were disproportionately burdened with paying court debt for their families.”

People have also been forced to take extreme measures to pay off their debt, some even becoming desperate enough to commit crimes to get the money. Four in 10 of those surveyed in Alabama Appleseed’s report say they’ve committed at least one crime to pay off their fines or fees. The people surveyed admitted to selling drugs, stealing and robbery, engaging in sex work, passing bad checks, gambling, and selling stolen items to make money to pay off their court debt. Some people who were fined for traffic offenses, which are not criminal acts, committed felonies to pay off their tickets.

‘Some people who were fined for traffic offenses, which are not criminal acts, committed felonies to pay off their tickets.’

Even though imprisonment for nonpayment of court debt was outlawed in a 1983 Supreme Court ruling, the practice persists due to legal loopholes. In fact, in some regions, people who owe money go to jail to “lay out” or “sit out” fines and get credit toward the amount owed at a set rate per night.

Organizations working to change the system of fees and fines, like the ACLU of Northern California, believe a major shift is needed to help Black Americans and other people of color out of the debt spiral that comes from legal financial obligations.

Brandon Greene, the racial and economic justice director at the ACLU of Northern California, says, “The costs associated with court operations should not be funded on the backs of Black and Brown communities who are already overpoliced and overburdened by a criminal legal system built on racialized policing. The racism inherent in these systems leads to serious consequences—like racialized wealth extraction that then leads communities of color into economic hardship.”

Nelson of the Alabama Appleseed Center for Law and Justice says that when it comes to the racial wealth gap, overpolicing and overcriminalization of Black people are just part of the picture: “Alabama has a racial wealth gap which has accumulated over centuries, starting with slavery, convict labor, and Jim Crow. Factors like redlining, lending discrimination, educational inequities, lack of access to many institutions of higher learning, and deliberate race-based exclusion from many professions, mean that even after slavery ended Black families in Alabama have had less opportunity to accumulate wealth. Over the centuries, white Alabamians have had greater opportunities to accumulate and hold on to wealth, while also avoiding race-based discrimination that continues to impact their Black peers.”

Positive Steps

In her work at the Fines and Fees Justice Center, Weiss has seen 22 states substantially curb or eliminate driver’s license suspensions for unpaid fines and fees in the past three years. In dozens of states, the imposition of fees has been eliminated from the juvenile justice system. Four cities and the state of Connecticut have eliminated charges for phone calls from jails or prisons. In 2020, California eliminated 23 fees from its criminal legal system, including public defender fees, probation fees, and electronic monitoring fees. Florida eliminated 17 more fees this year. New York’s legislature is also considering a bill to eliminate criminal legal fees.

“The good news is that there is growing recognition of the tremendous harms caused by fines and fees from across the political spectrum,” says Weiss. “We are seeing reforms in red, blue, and purple states and localities. The most successful reform efforts are being driven by broad coalitions including and informed by impacted community members themselves.”

However, there is still more work to be done. Nelson proposes scaling fines to people’s ability to pay, as well as instituting time limits on debt.

“We could introduce a limit on how long they’re expected to pay, so for instance if you make timely payments for a year the rest of your debt is waived,” says Nelson. “You’d see interesting results if payments were time-limited. I think some people don’t pay regularly because they don’t see an end to payments and just feel hopeless. Half the people I surveyed thought they would be paying until they die. Why should financial penalties be a life sentence?”

Legal fines and fees do not only hurt the offenders they are meant to punish. The current system of court debt impacts all Americans socially and economically.

“When people’s lives are so disrupted by the consequences of debt, we all suffer the consequences,” says Nelson. “We’re keeping people out of the workforce. We’re interrupting their ability to parent their kids, care for elderly parents, stay in school. We’re punishing them into oblivion. The state is holding itself back by levying punishments that are too heavy for its residents to bear.”

|

Help keep us strong. Become a Shelterforce supporter today. |

Comments