This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Community Ownership Takes Center Stage

Photo courtesy of Northern California Land Trust

Community development has long made attempts at wealth building, with a focus on trying to find successful or innovative models that can be replicated. And yet the transformational change we’ve sought hasn’t materialized. Displacement of a community’s longtime residents continues to soar, and the median wealth of Black households sits at $23,000 in contrast to $184,000 for white households. My work with the Strong, Prosperous and Resilient Communities Challenge (SPARCC) suggests there is more promise in centering the communities we work with instead of trying to carbon copy “best practices.”

SPARCC has been working in six metropolitan regions for five years. We invest in and nurture relationships with multidisciplinary groups that bring together community residents, public and private sectors, and local governments in each city. From the very beginning of our partnership in 2016, community partners and residents alike have shared a growing fear of displacement—and yearned for community ownership as a safeguard against these growing pressures. As a result of these ongoing conversations, we’ve put an extensive amount of time and energy into researching community ownership models, their benefits, and how they function.

These models operate in vastly different ways, require different contexts to be successful, and offer different benefits. While each of the groups SPARCC has worked with agreed that community ownership is critical to building wealth in Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color, the exact model that each city—or even communities within the same city—ended up selecting differed.

We don’t have an exhaustive tool detailing the ideal enabling context for each model, but here are some lessons SPARCC has learned about the process.

-

Community Must Frame What Problem the Model is Trying to Solve

Community ownership models could be a huge boon to communities of color—but only if the models focus on advancing the specific concerns of those community members they are intended to benefit.

The solution must fit the problem. Sometimes it’s clear. If the problem the community is most concerned about is low-income homeowners facing increasing property taxes, building accessory dwelling units is a good fit; creating a multifamily co-op is not. But sometimes it’s more subtle, and we have had to keep learning and adjusting, like when our organizing partners helped us understand that a particular group of renters in Oakland were more concerned with stability than affordability and were willing to increase their own rent to become Oakland Community Land Trust owners.

-

We Must Understand the Mechanics of Building Wealth

Since World War II, building wealth through home equity has provided enormous benefits for a largely white middle class. But getting that wealth, and leveraging it to benefit those families required preexisting wealth to invest, income growth, property appreciation, fair appraisals, and access to honest, market-rate capital. Given that Black, Brown, and Indigenous people have lacked access to all of the above, we need to carefully consider what must be in place for ownership strategies to truly benefit our communities and current residents.

In Denver, for example, we are working with BuCu West to purchase commercial buildings that they will use to preserve cultural businesses and build wealth for small-business owners. But the devil (and the proposed benefits) remains in the details. This final structure must at the same time help grow the current businesses, give the individual business owners the certainty and control of property ownership, be selective about future commercial tenants to bolster the cultural character of the corridor, and anticipate the mechanics of selling the building to a future owner.

Similarly, community land trusts (CLT) must establish resale formulas that calculate future sale prices based on factors such as the original sale price, length of ownership, market appreciation during ownership, major repair and upgrades during ownership, and affordability target as a percentage of area median income. Just as with conventional homeownership, there is no guarantee of a positive return on investment. A CLT effort must consider its best guess of those inputs to the resale formula and project whether that particular CLT ownership opportunity can fairly claim asset-building to be among the benefits of ownership.

As more local efforts, national proposals, and philanthropic strategy center wealth building and community ownership, it’s worth considering the nuances of different structures. When a community’s goals focus on building wealth for those who have been systematically prevented from doing so, the process of testing ownership models must involve asking “Who benefits?” “Who’s burdened?” and “How?” (the central questions of a racial equity impact assessment).

-

Ask if Ownership is the Right Kind of Wealth for the Goal

The projects coming from our local partners regularly center building wealth. Communities of color desire access to the intergenerational asset-building opportunities long enjoyed by the white middle class so that they too can start businesses, send kids to college, earn investment income, and have liquid savings for emergencies. Wealth allows a person or family to have access to capital, supplemental income, and reserves in the event of emergencies like global pandemics and economic downturns.

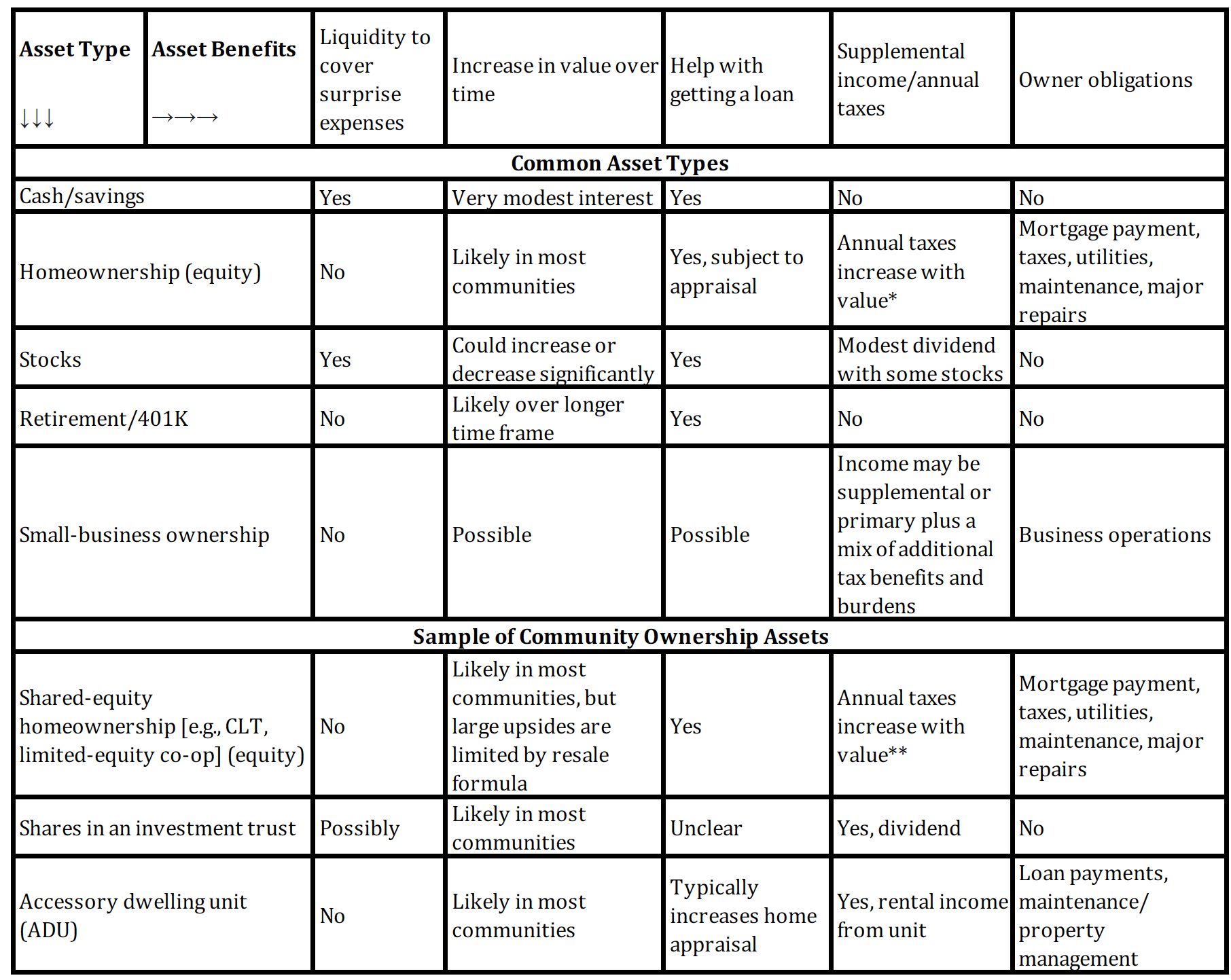

But different kinds of assets serve these different purposes more or less well. The chart below details some of the asset types, and their associated benefits. (Disclaimer: This chart is a starting place to consider tradeoffs and isn’t exhaustive of asset classes, benefits, or owner obligations.)

*Increases in taxes might outpace any increases in the homeowners’ salaries, in single-family home units. Despite an increase in value of the property, families may be unable to handle the increasing tax burden. **Taxes increase on communally owned property as well but typically are less than they would be with traditional ownership.

Here are few examples of the benefits and limits of some of these models:

Community land trusts, which offer a type of shared-equity homeownership, purchase and hold property in trust for the long-term benefit of current and future CLT homeowners. In appreciating markets, CLT homeowners can accumulate significant amounts of family wealth, while the units remain affordable for future buyers. However, as with any homeownership, that wealth is not very liquid.

Example: Northern California Land Trust processed a resale in Berkeley last year on Haskell Street. The family had purchased in 2010 at $200,000 and sold in 2020 at $300,000. Both amounts were at the affordability level for families at 80 percent of area median income. The $100,000 gain after sale is the kind of wealth that changes a family’s life trajectory, but it would have been hard to access it to help with a surprise expense or job loss while they were still living in the home.

Investment trusts and other crowdfunding efforts give folks the opportunity to own real estate in very small shares. This supplements income, but often doesn’t represent an asset that shareholders can borrow against.

Example: Several efforts are underway to replicate elements of the Community Investment Trust in Portland, Oregon, which allows residents in the community to purchase shares in a rehabilitated, community-serving retail strip center. These shares increase in value, pay a small dividend, and can be sold back to the trust as necessary.

Accessory dwelling unit (ADU) initiatives are helping low-income homeowners retain ownership and turn paper wealth into current income.

Example: West Denver is a working-class area of mostly ranch-style single-family homes. For decades, it was an affordable place to buy a home. But from 2015 to 2017 alone, home values (and property taxes) in the area increased 50 percent while residents’ median household income stayed approximately half of Denver’s average. Currently Denver is experiencing a greater displacement of Hispanic people than any other major U.S. city. ADUs emerged as a strong solution to address residents’ concerns about displacement, after dozens of community listening sessions and a housing assessment led by West Denver Renaissance Collaborative. By placing a studio apartment or one- to two-bedroom home in an empty yard or over a garage, residents would be able to earn extra income to cover rising property taxes while providing stable, long-term housing for another family.

With so many approaches to community ownership and wealth building, it is critical that practitioners listen closely to those they intend to serve and develop a nuanced understanding of their wealth-building needs and desires. What kind of wealth are folks asking for and what do they need those assets to do for them and their families? Is the proposed community ownership model a good fit to deliver that kind of wealth or would something else likely be more successful?

No single model or capital tool is going to be ideal for every community, and individual communities may need more than one wealth-building tool to bolster the economic resilience of residents. Much as the white middle class has been lifted by homeownership, retirement savings, and emergency cash savings, communities may look forward to a more economically resilient future by combining tools like CLTs with community-owned commercial properties and shares of other income-generating models.

|

Please consider supporting our small and dedicated team on Patreon. |

Comments