This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Community Ownership Takes Center Stage

Northcountry Cooperative Foundation’s Julie Martinez introduces herself to the Sky Without Limits residents at a meeting on June 2. Photo courtesy of Victoria Clark, via Northcountry Cooperative Foundation

During her tenure at Northcountry Cooperative Foundation (NCF), Victoria Clark has become an expert at helping mobile homeowners buy the land where they live. In many places, residents of mobile home parks have suffered as park owners sell out to private-equity firms that then jack up lot rents and reduce services. But since 1999, with assistance from NCF, 823 households in 12 resident-owned communities (ROCs) around the Upper Midwest have kept their rents low, invested in infrastructure, made decisions democratically, and enjoyed the pride of ownership.

“We’re essentially providing assistance to small cities. They maintain their own roads, water, sewer, electrical. I mean, holy cow,” says Clark, executive director of the Minneapolis-based nonprofit. “Our ROC program is amazing, it works really well, and we’re doing it at scale.”

Yet while resident-owned communities help mitigate the region’s housing affordability crisis, Clark thinks NCF could do much more. She notes that Minnesota has one of the nation’s worst racial gaps in homeownership: while 77 percent of white families own their homes, among households of color and Native Americans the rate is 44 percent. For Black families it is just 27 percent. In Minneapolis a city-commissioned study found a shortage of homes affordable to buyers earning below $60,000, and a severe shortage for those with incomes under $30,000.

To help address that vast need, NCF is tiptoeing into the field of urban, multifamily cooperatives. Clark and her colleagues have been working with the South Minneapolis tenant group Sky Without Limits, which is in the process of gaining ownership of five apartment buildings after a lengthy struggle with a negligent landlord. NCF is hoping to serve as the group’s technical assistance provider when it sets up a formal cooperative structure.

“That’s going to be our first foray into the multifamily world,” Clark says. “It’s exciting for us organizationally because we want to get into this space. We want to figure out how to do multifamily limited-equity co-ops.”

‘Legally, structurally, financially it’s very different … [But] on the co-op governance side a lot of it is transferable, because you’re talking about democratic memberships and boards.

NCF has also looked into developing senior cooperative housing, and it is conducting a study of naturally occurring affordable housing around the state so it can identify buildings that are good candidates for cooperative conversion, she says.

Clark acknowledged that multifamily co-ops differ in important ways from mobile home ROCs. A resident-owned community owns land but not living units, while a traditional co-op owns and maintains its buildings. When a resident-owned community buys a mobile home park, it arranges a financing package and borrows against the land, whereas multifamily acquisitions are typically financed by tenants’ individual share loans in addition to the mortgage. As it enters multifamily organizing, NCF may also have to develop different technical assistance contract terms and funding sources for its work than those used in the standard ROC model.

But Clark says the essential work of organizing residents and helping them run their cooperatives is similar in both arrangements, and she believes her organization is well-positioned to add multifamily communities to its portfolio. Along the way NCF will also look to real estate developers and to experts at the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB) in New York for guidance and advice.

“We’re doing this in the Wild West of real estate, which is manufactured home communities,” Clark says. “If we can crack this nut that’s so complicated, that has all these layers of complexity because people own their own individual homes, why can’t we do the same type of thing in the multifamily rental world?”

Strengthening the Network

Tenant groups have been creating affordable cooperative housing for decades, particularly in New York, and activists have reported a surge of new interest from municipalities, tenants, and local nonprofits in the last few years. Several new limited-equity co-ops (LECs), which are designed to keep rents low and maintain long-term affordability, have popped up around the country. A few cities and states are considering passing laws similar to Washington D.C.’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) that would facilitate cooperative conversions.

In the past, UHAB worked with local housing practitioners to help create cooperatives in Boston, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Oakland, Des Moines, Omaha, and Washington, D.C., UHAB Executive Director Andrew Reicher says. Some of those co-ops are still operating, but as federal funding declined over the years many of the local organizations that helped create and nurture them disappeared. Restoring and expanding that provider structure is essential to the endurance and growth of co-ops, Reicher says.

“Maintaining those groups on the ground [that] can provide ongoing trainings for new board members, help them each year with their budget, help them with an election, making sure they’re in compliance with their regulatory agreements, whatever it is—that support system is really what’s important.”

NCF is one of 12 affiliates of the ROC USA Network, a New Hampshire nonprofit that coordinates collaboration among members and helps finance conversions. ROC USA affiliates work in 20 states, and with their ample experience they could play an important role in rebuilding the national support system for housing cooperatives, Clark and others say.

“Having the ROC groups, who are providing technical assistance to a cousin sort of co-op, learn those skills and be able to deal with multifamily housing is a great thing,” Reicher says.

ROC USA is deeply focused on mobile home parks and is not interested in adding multifamily housing to its brand, CEO Paul Bradley says. But he says affiliates like NCF are welcome to expand and branch out into different areas, and he agreed that their skills are clearly applicable to multifamily organizing.

“All of our affiliates are involved in multiple lines of business, so multifamily co-op work would be a new line for them,” Bradley says. “Legally, structurally, financially it’s very different. It operates under a different tax code. [But] on the co-op governance side a lot of it is transferable, because you’re talking about democratic memberships and boards.”

Middle-Income Co-ops

When Brian Eng, a housing developer in Portland, Maine, and UHAB board member, became interested in co-ops a few years ago, his search for partners soon led him to the Cooperative Development Institute (CDI). A ROC USA affiliate in Portland and the largest ROC technical assistance provider in the country, CDI has assisted 53 mobile home park conversions in Massachusetts, Maine, Vermont, Rhode Island, and Connecticut.

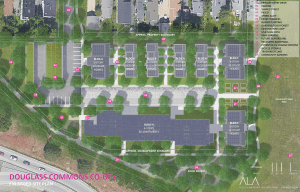

Maine Cooperative Development Partners’ plans for Douglass Commons include an apartment building with 56 units, and seven buildings comprising 52 limited equity cooperative units. Photo courtesy of Maine Cooperative Development Partners

“UHAB has a lot of intellectual capital, but we don’t have a lot of people, so we need local affiliates if this is going to happen,” says Eng, who grew up in cooperative housing in New York. When Eng set out to develop co-ops in Portland, CDI played a key role in bringing the idea to city council and explaining its benefits, he says. “People in Maine just don’t have a conception of a cooperative. It might as well be from Mars, even though it’s not really that foreign.”

Eng’s interest stems from watching home prices soar in Portland over the last two decades, due in part to an influx of wealthy new residents from other states. The high prices have forced public sector employees like teachers and police officers to live well outside the city and commute long distances, he says.

“Ironically, a lot of people who are part of the public domain in Portland cannot afford to live here as owners. That’s the gap we’re trying to fill. There has just not been the creation of housing within the Portland city limits for people who work for the city,” he says.

Eng had started exploring cooperative development after reading about Raise-Op, a pioneering affordable housing co-op in Lewiston, Maine. Through that group he connected with CDI, which has provided technical assistance services to Raise-Op and also works with agricultural and business cooperatives. CDI staffers advised him to speak with a supportive Portland city councilor and made a presentation to council about housing cooperatives.

Portland subsequently solicited developer proposals for a set of city-owned parcels and last year selected Eng’s firm, Maine Cooperative Development Partners (MCDP), to build two “missing middle” projects. They are meant for residents who cannot afford Portland prices but do not qualify for more deeply affordable housing support.

Eng said CDI has played a key role in the effort so far and he expects the organization will formally sign on as a technical assistance provider, with help from UHAB. CDI and Eng’s firm have already been organizing prospective residents to join the cooperative, including several immigrant families.

“The resident support is crucial,” Eng says. “MCDP is not going to be operationally involved after people move in; that’s where CDI is going to play that crucial role.”

Creating a Model

Even before Eng contacted them, CDI staff had been thinking about moving into multifamily work and were talking with Portland officials about how city-owned parcels could be used to address the need for affordable housing, says Doug Clopp, head of media and governmental affairs at CDI.

Council approval of the two projects over competing proposals bodes well for the future of affordable co-ops in New England and beyond, he says.

“We’re very excited to see how this project rolls out, and hopefully it’s a model for other cities across the country. It’s a great story about bringing together city resources, federal resources, private sector, and public nonprofits like CDI—that unique collaboration, where everybody’s kind of rowing in the same direction,” he says. “You can build a cooperative, purposeful community in a city facing huge, huge gentrification issues.”

Clopp described the movement across New England to create more limited-equity cooperatives and other housing cooperatives as “nascent.” Interest is driven by the experiences of the 2008 recession and the pandemic, along with the “craziness” of the real estate market, he says. Advocates are currently trying to pass a TOPA law in Massachusetts, which already has over 100 housing co-ops of various sizes and types across the state.

“Clearly the demand is there, so the question is, who’s meeting the demand?” Clopp says.

A model like the Portland project, or Raise-Op’s work in Lewiston, where it has three small multifamily co-ops and is planning to build two more, could also work in other older mid-size industrial cities like Worcester and Springfield in Massachusetts, he says. CDI would bring its deep experience in community outreach and organizing and learn the rest as it goes.

“It’s that old expression, you make the path by walking it. Do we know where that leads? We don’t. But you’ve got to try,” he says.

Clopp says the organization would have to increase its technical assistance capacity generally. Ideally other nonprofits would also step up with projects and multiply the number of new affordable housing opportunities across the region.

“We want to work cooperatively,” he says. “If you had 10 organizations doing this it would be a teaspoon in an ocean to meet the demand. So let’s see if we can put successful models together that can be replicated by anyone.”

|

Please consider supporting our small and dedicated team on Patreon. |

Great piece. I love seeing Julie Martinez and Northcountry Cooperative Foundation front and center!

I would go further on my comments in the article: ROC USA is focused on scaling community ownership of Manufactured Home Communities – a sector of 45,000 communities and 2.7M homes that’s critical to low-wealth homeowners in 49 states. (We serve 277 and 19,000 in 18 states today. As you can see, the runway is long!) We aim to make resident ownership viable and successful from coast to coast in this one sector. We bring disciplined focus in a single, vital affordable homeownership sector.

We absolutely cheer on our colleagues in the multi-family co-op space. I am a huge fan of UHAB!

When I read, “replication” as the scaling strategy, I was not surprised. That’s been the prevalent strategy for decades in a range of sectors. However, at this early resurgent stage for MF co-ops, I encourage those interested in it to consider what is needed to scale ownership and impact, and figure out a way to do that. We need to challenge ourselves to contemplate scalable solutions that can produce significant impact.

The nonprofit community development sector is not well-known for scale. Most of us in community development do not have that experience. For 15 years, I have been focused on this question: How can we make community ownership viable and successful nationwide? I am hopeful some colleagues in MF co-ops are asking themselves the same. ROC on! Paul

I have been interested for years in cooperative housing and mobile home park self- governance. I just never found anything to really start with. I am in the Sacramento CA area and would be keen on meeting those who share the interest. Please email me any thing pertinent to either here or New York state, both places where I have family. Thank you, those who have organized all the groups mentioned in the original article.