Photo by F. Muhammad from Pixabay

Medical and public health research has established clear and persuasive links between poor housing conditions and negative outcomes for residents’ physical and mental well-being. Inadequate housing can exacerbate chronic health issues, expose occupants to environmental toxins, and heighten injury risks, which are especially hazardous to children and older adults. Residing in substandard housing is also associated with increased risks of depression and anxiety, and may have a particularly demoralizing impact on children. In addition to these widely documented health impacts, inadequate housing can worsen residential instability among low-income renters, leading to poor health outcomes for both adults and children. For low-income homeowners, the inability to afford needed repairs is a common financial stressor, and evidence from the foreclosure crisis suggests a strong link between struggling with housing costs and worse self-reported health.

Measuring and Understanding Home Repair Costs

Making the case for health-enhancing investments in housing quality requires understanding the scope and magnitude of repair needs, as well as the ability to identify the households at the greatest risk of harm. However, despite growing cross-sector recognition of the importance of housing to health outcomes, we have had relatively little information on the condition of the national housing stock. To address this knowledge gap and provide an intuitive, policy-relevant scale of disrepair, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia and PolicyMap developed a new housing quality measure based on the cost of addressing housing deficiencies identified in occupied units.

This report can help organizations make the case for the health impacts of their repair work, as well as explain why other groups should put home repair high up on their respective agendas.

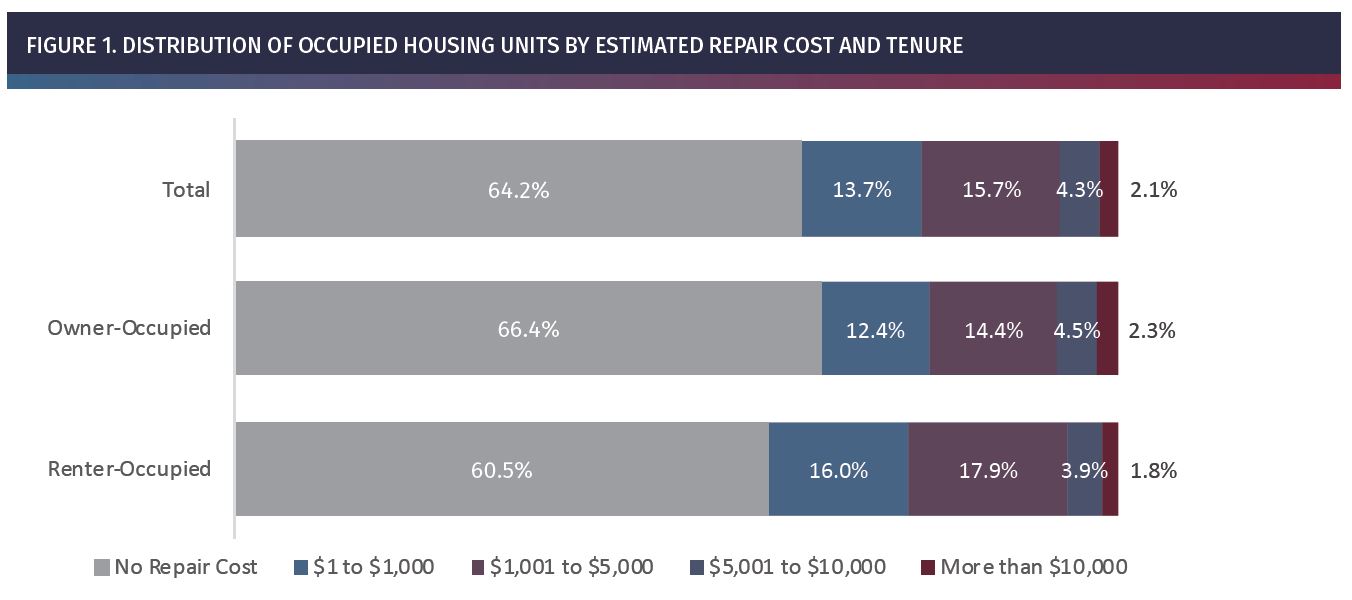

In the 2017 American Housing Survey, which was sent to over 80,000 units across the country, we found that more than one-third, or 35.8 percent, of households nationwide reported at least one housing problem. These problems range from minor maintenance issues to severe and costly structural deficiencies. For more than 75 percent of households, home repairs were estimated to cost $5,000 or less. Overall, we estimate that the total national cost of addressing needed repairs in occupied housing was $126.9 billion in 2018. However, within any given year some units will undergo improvements while others will fall into disrepair. In fact, many of those reporting repair needs were middle- and upper-income households whose experiences with disrepair are likely to be temporary.

A subset of these aggregate repair costs—$50.8 billion—pertained to units occupied by low-income renters and homeowners (those with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or a maximum income of $40,840 for a family of four), who are less likely to be able to afford repairs or move to a higher-quality unit. These low-income households accounted for just over half of renters with repair needs and one-quarter of homeowners with repair needs. Prior research suggests that the health impacts of investments in housing quality are likely to be strongest for interventions that target more vulnerable residents.

Understanding the Home Repair Needs of Vulnerable Households

In our report, my coauthors and I created a typology of households with repair needs grouped by tenure, income, and key household and unit characteristics. The following are examples, informed by actual anonymous survey responses, of low-income households with repair needs. These examples are intended to illustrate and contextualize the types of housing quality issues that vulnerable households experience.

Low-Income Homeowners

We estimate that there were roughly 6.6 million low-income homeowners whose houses need repair, with an average total repair cost of over $3,800. Our typology for low-income homeowners is based on the age of their home and the length of time they have lived the unit.

- New Homeowners in Moderate-Age Units: A married couple living in a two-bedroom manufactured home in a rural area of the South share a home with their teenage son, their adult daughter, their daughter’s spouse, and their grandson. The total household income is modest, putting them just over the federal poverty line (roughly $33,000 for a household of their size). Their monthly housing costs are low, but they are living in overcrowded conditions, which may put the youngest members of their household at risk for negative behavioral and educational outcomes. They have lived in their home for less than five years but already have several repair needs. In addition to a broken window (which may present an injury hazard), they have a leaky roof and weekly sightings of cockroaches, both of which are potential asthma and allergy triggers, and cockroaches may contribute to unsanitary living conditions. The average estimated repair cost for households in this group was roughly $3,110.

- Medium-Term Homeowners in Older Units: A married couple with two young children live in a single-family home in a large Midwestern metropolitan area. Their aging home shows clear signs of physical deterioration, including leaks from both the roof and basement, a damaged brick façade, peeling paint on interior walls, and a broken window. In older homes, peeling and chipping paint can present a lead exposure risk. Additionally, visible disrepair is associated with negative impacts on the mental well-being of occupants and can contribute to parental stress, with implications for children’s emotional well-being. Though the couple has built up some equity in their 14 years of residing in the home, low-income households like theirs often struggle to access conventional home improvement financing. The average estimated repair cost for households in this group was roughly $3,920.

- Long-Term Homeowners in Moderate-Age Units: An 84-year-old woman lives alone in a townhome in a large Northeastern metropolitan area. She has lived in her home for over 40 years and owns it outright, keeping her monthly housing costs relatively low. However, the foundation of her home is cracked, and exposed wiring presents a clear electrocution and fire risk. While the cracked foundation may not pose an immediate hazard to the woman’s health, the costly repairs would be financially burdensome given her below-poverty-level annual income of $9,600. For older adults living on fixed incomes, high housing-related costs may compete with other necessities, such as health care and food. The average estimated repair cost for households in this group was roughly $4,190. Furthermore, prior research suggests that low-income older adults in inadequate housing may be more likely to have additional unmet adaptive modification needs, which are critical for enabling them to safely and comfortably age in place.

Low-Income Renters

We estimate that there are roughly 9 million low-income renter households with repair needs, with average estimated repair costs of over $2,800. Our typology for these households is based on the age of the unit and whether it is a single-family home or in a multifamily building.

Unlike homeowners, renters are generally not responsible for addressing needed repairs. However, roughly one-third of renters who contacted their landlords about repairs reported having moderate or substantial difficulty getting the problems fixed, and close to two-thirds of Black and Hispanic renters reported having at least a little difficulty.

- Renters in Older Single-Family Homes: A single woman lives with her three young children in a single-family home in a medium-sized Midwestern metropolitan area. Her annual income of $22,000 falls below the federal poverty line, but she has a housing voucher that keeps her rent affordable. The house, built prior to 1920, is big enough to meet her family’s needs, but it has a leaky roof and heating equipment that occasionally breaks down during freezing Midwestern winters. Cold home environments can exacerbate respiratory illnesses and are associated with elevated rates of anxiety and depression. However, using space heaters to compensate for the faulty heating system could lead to costly electric bills that might exceed her voucher’s utility allowance. The average estimated repair cost for households in this group was roughly $4,160.

- Renters in Older Multifamily Units: A veteran lives alone in a large Northeastern metropolitan area. His apartment is a modest two-bedroom in a four-unit building that was built in the 1920s. He is disabled and receives Supplemental Security Income that puts him just below the federal poverty line ($12,060 for a single person), but he receives no additional housing assistance. As a result, even though the rent for his apartment is quite low, it eats up more than half of his monthly income. The walls of his apartment are cracked with peeling paint, and his living room shows signs of mold. Each of these deficiencies is a potential allergen trigger, and prolonged exposure to mold may damage the lungs. Given the dearth of accessible low-cost rental housing options throughout the Northeast, he is unlikely to find a better-quality unit in his area that he can afford. The average estimated repair cost for households in this group was roughly $2,200.

Informing Practice

In addition to the health and quality of life impacts outlined above, addressing the repair needs of low-income households supports several core priorities of the community development field. First, the ability to address costly or unanticipated repairs is pivotal to the financial sustainability of low-income homeownership. One study that followed up with hundreds of low-income homebuyers who had participated in pre-purchase counseling programs found that, within two years of purchasing their homes, about half were facing unexpected maintenance costs and one-third had significant repair needs that they could not afford to fix. Second, many of the lowest-income renters experience a double burden of inadequate and unaffordable housing, requiring assistance in both dimensions to meaningfully improve their housing security. Lastly, investing in housing quality can prevent structures from falling into severe disrepair, lessening the risk of property abandonment that can have harmful spillover effects at the neighborhood scale.

Though we found that most low-income homeowners have relatively modest repair needs, the average repair cost of $3,800 still exceeds what many would be able to pay for out of pocket. Medium- and long-term homeowners with repair needs are likely to have built significant home equity that could be leveraged to cover the expense of repairs. However, the loan amount needed to cover basic repair costs is likely to be too small for traditional lenders. Furthermore, homeowners might find the process of obtaining conventional home equity financing too cumbersome in comparison to faster, high-cost loan options. Community development financial institutions may be able to help fill this gap in access to affordable, small-dollar repair loans, diverting homeowners from resorting to potentially wealth-stripping products.

For homeowners who are unable to afford additional monthly payments or are reluctant to encumber their homes with more debt, grants and sweat-equity programs offer an important alternative. Many municipalities offer grant programs to assist low-income homeowners with critical repairs, though applicants may find these programs challenging to navigate and funding may be insufficient for the local level of need. The national organization Rebuilding Together and its network of local affiliates engage tens of thousands of volunteers each year to provide free health- and safety-enhancing repairs for low-income homeowners. Affiliates often coordinate with community-based organizations that can help identify blocks with high concentrations of homeowners with repair needs. The organization’s She Builds initiative is tailored to low-income households headed by single women, who our research indicates are disproportionately affected by housing disrepair, equipping them with the skills and resources to address common repair needs and maintain a safe and healthy home for their families.

Addressing quality issues in the rental housing stock is less straightforward, requiring municipalities to strike a delicate balance between holding negligent landlords accountable and avoiding destabilizing or pricing out vulnerable tenants. Code enforcement has long been the primary tool for addressing substandard housing, though some have raised concerns that these efforts exacerbate existing socioeconomic disparities in practice. The Cities RISE program has developed a framework for applying a race and equity lens to code enforcement, beginning with a deep assessment of the equity implications of existing municipal policies and procedures. The program emphasizes the critical role of meaningfully engaging residents and stakeholders to establish more collaborative relationships with code enforcement officials.

Community organizations play a central role in this process by facilitating the participation of residents who are directly affected by inequitable code enforcement practices. Robust tenant protections and engagement can complement these efforts: In one notable example, residents of a derelict apartment complex in North Carolina banded together to pressure a sale to a more responsible property investor. For the segment of low-cost, low-quality rentals owned by well-intentioned but under-resourced landlords, low-cost repair financing may help, though robust affordability protections would be needed to stem the loss of low-cost units.

The estimated price tag of over $50 billion to address repair needs in 15.6 million low-income households across the county may seem daunting. However, integrated approaches to improve housing affordability, stability, and quality are already the subject of innovative proposals and initiatives that bring together the resources of the health care and housing sectors. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention even identifies providing affordable home improvement loans or grants to low-income homeowners as a high-impact strategy for addressing upstream causes of poor health. Growing the evidence base on cost-effective, quality-of-life enhancing interventions would help bolster these collaborations. Furthermore, beyond the subset of repair needs with direct links to physical maladies, the connections between housing quality and residents’ mental and financial well-being support the case for more broad-based investments in improving the housing circumstances of low-income households.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System.

Has this type of study been done in St. Louis, MO? Who can I connect with at the Federal Reserve Bank in St. Louis?