In the fall of 2018, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) initiated an effort to modernize the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). Advocates are concerned that these efforts will mainly focus on weakening oversight and regulation. Regardless of one’s position on that issue, the banking industry in general, and indirectly the CRA, has been undergoing significant change, with more and more financial activities moving away from brick-and-mortar stores to the internet. Like any policy, CRA needs an update from time to time. But modernization efforts should be done in such a way as to build upon successful previous efforts, expanding access and community investments to more underserved areas. The CRA certainly faces challenges when it comes to incentivizing private sector investment in underserved rural areas.

CRA in Underserved Rural Areas

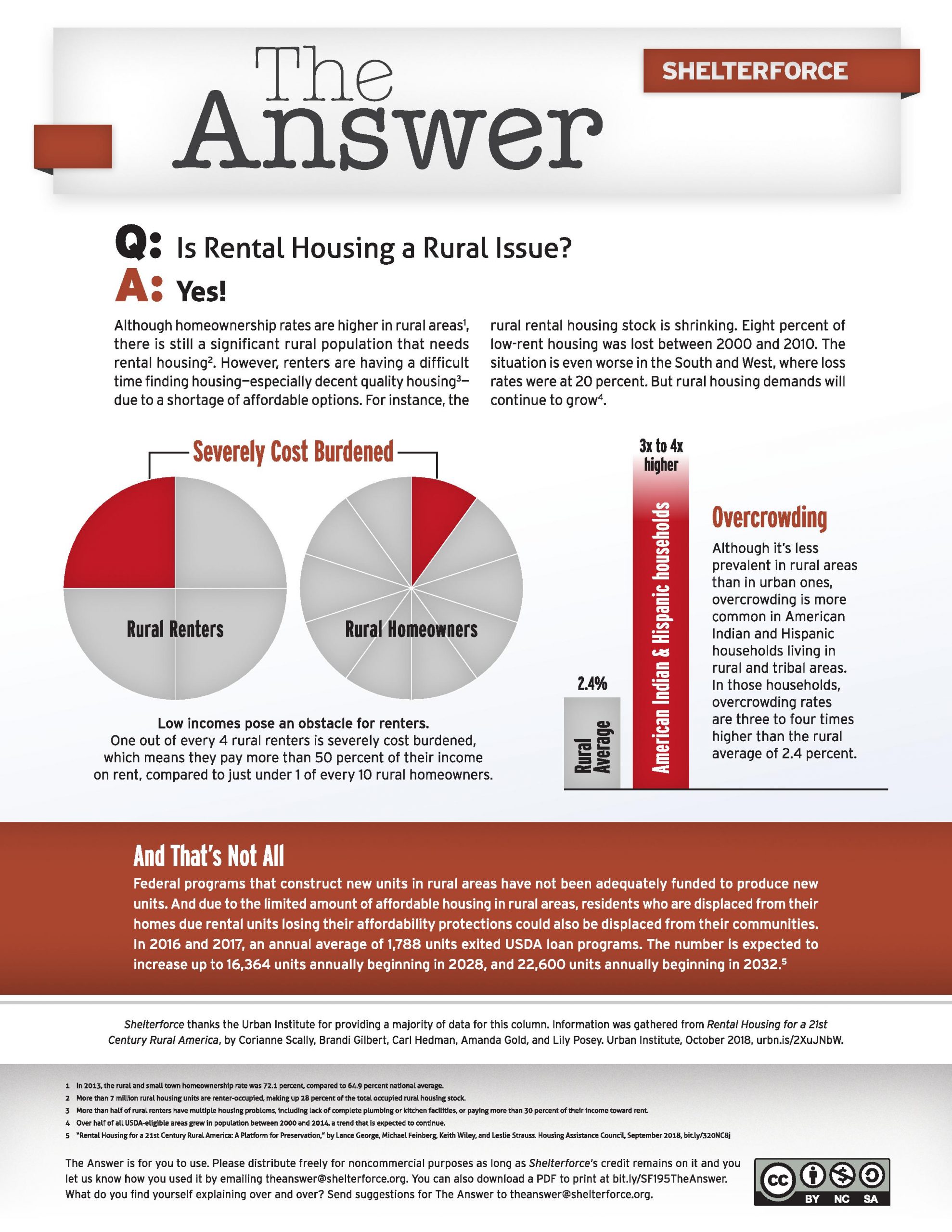

CRA has been highly successful at encouraging investments, amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars to date, in what had been underserved areas. Even with this success, however, CRA-related community development investments and activities are uncommon in rural areas where banks are scarce. For years, financial regulators have noted that the CRA needs to be better at promoting investment in underserved rural areas.

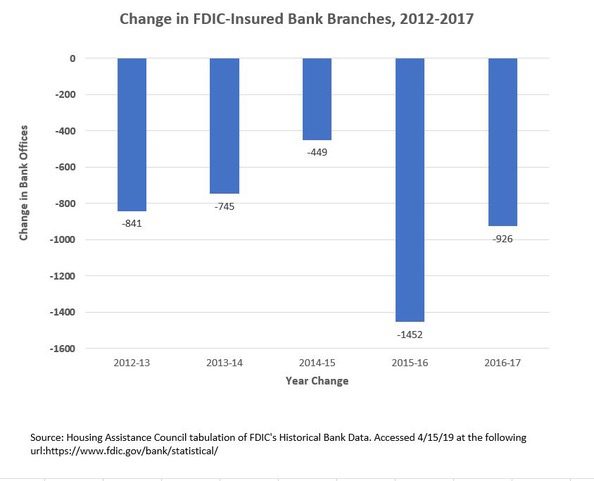

A major factor limiting the CRA’s effectiveness in reaching these areas is the way assessment areas are defined. Regulators evaluate lenders only on what they do or don’t do in their respective service or assessment areas. The CRA defines assessment areas primarily as census tracts that contain a deposit-taking bank branch or ATM. Given the scarcity of bank branches in thinly populated rural areas, CRA oversight is limited and likely to get worse because of the continuing trend in bank branch closings.

A related factor is that CRA exam rigor largely correlates with lender asset size. Large-asset banks, institutions with assets totaling $1.28 billion or more, experience thorough exams—retail lending, service, and community development tests—while small-asset banks, institutions with assets totaling less than $321 million, experience less thorough exams (retail lending alone).

Small-asset lenders are then not required to engage in community development efforts. But because the lenders that primarily serve rural communities are small-asset lenders, this means community development activities are not scrutinized.

For most large-asset institutions, on the other hand, a small percentage of their assessment area is rural and so rural areas are often not a focus. In addition, for large lenders with multiple assessment areas in different states, the examination process often involves full reviews of certain areas, usually where most bank activities occur, and less thorough reviews in the remaining areas—which often include rural areas, further limiting the focus on rural.

The problem is compounded by the fact that the overall number of banks declined dramatically, from 18,000 in 1985 to less than 6,000 in 2017, with most of the decline involving small-asset lenders, many of which worked primarily in rural areas. Where once a bank’s decision were made at a local, rural level, they are now made in a distant metropolitan area. This means that even if a bank serving an area might now technically be larger and have more CRA requirements, it may not have the connection with the community that is necessary to prompt activity.

The importance of having such connections can be seen in efforts by the Community Resources and Housing Development Corporation (CRHDC) to develop farm-worker housing, known as Sol Naciente, in Fort Morgan, Colorado. Sol Naciente is a 50-unit rental housing development built in 2016 that, among the many funding streams involved, received a construction loan from Wells Fargo that was CRA eligible. According to Robin Wolff, director of marketing and resource development at CRHDC, a key factor in the process was the strong working relationship between CRHDC and Wells Fargo personnel, which was made possible because both organizations frequently attend similar housing conferences and events and both have offices in Denver (Fort Morgan is 70 miles away from the city). These types of direct connections between large-asset lenders and local nonprofits are likely missing in many rural communities, which surely limit CRA’s effectiveness. The Sol Naciente project showed that such efforts are possible.

Why Modernize?

One rationale for modernizing the CRA is that it is still based primarily on a 1970s banking environment where most transactions occurred in a bank branch and financial products were much more limited. The number of bank branches has declined for five consecutive years, and financial products have become numerous, complex, and more accessible over the internet. How can the CRA be updated to reflect such changes, yet acknowledge the continuing importance, particularly for lower-income and aging customers, of things such as in-store services? How can this be done in such a way as to expand opportunity?

Possible Approaches

Many advocates fear that OCC’s efforts could limit oversight and regulations under the guise of modernization. For example, proposals to create a single, metric-based CRA exam could reduce or eliminate the role of the community in the process. Even with these concerns, CRA needs modernizing and there should be avenues to do that in a meaningful way that builds on the CRA’s previous success.

Federal Reserve Board Governor Lael Brainard put forth one of the more promising sets of ideas on CRA modernization in a March speech at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition’s “Just Economy” Conference in Washington, D.C. Among the many ideas she discussed, Brainard noted the possibility of having different assessment areas for different CRA tests. Currently, most CRA exams consist of up to three tests, depending on lender asset size, and all evaluations are based on the same assessment or service area (based on the location of banks’ deposit-taking branches/ATMs). Brainard mentioned a possible approach that would use traditional assessment areas for the retailing lending and services tests, but allow larger, more encompassing assessment areas for the community development test. This would affect the larger-asset lenders that are obligated by the CRA to engage in community development/investment activities.

While such an approach would mean local bank offices and service provision remain the focus of the CRA retail lending and services tests, the changes to the community development test could make other areas attractive for CRA-related investments. An affordable housing project in a rural low-income census tract that borders a lender’s current assessment area might now be a more attractive investment since it can be counted toward fulfilling a lender’s CRA community development obligation. “This could be to the benefit of credit deserts—those perennially underserved rural areas or small metropolitan areas that may not have a bank branch or, if they do, may not constitute a major market for purposes of banks’ CRA evaluations,” said Brainard at the Just Economy conference. It is this type of creative thinking, not simply assuming there can only be one assessment area, that is necessary to expand the reach of the CRA into more underserved markets.

Regardless of the method used, no one really disputes that the way in which areas are determined will change, at least to some degree, given the decline in the number of bank branches and the increase in online banking. Assessment areas should primarily reflect where a lender does its lending. The need to upgrade the CRA should not be used as a rationale for limiting regulation and lender requirements; however, modernization should seek to both better reflect where a lender engages in services and to expand the reach of CRA-related investment into an assessment area adjacent low- or moderate-income, or distressed and underserved census tracts and high-needs area markets (referred to here as “underserved areas”) more broadly where it currently does not occur. The idea should be to add to CRA-related investments, not simply shift from one community to another.

One consideration might be to expand the CRA ratings from four categories—substantial non-compliance, needs to improve, satisfactory, and outstanding—to include an additional top category. Lenders earning the additional top rating would have to first meet the needs of the traditionally defined assessment area, and, on top of this, provide services and investments in nearby underserved census tracts. The additional rating would be a way for a lender to distinguish itself from other lenders and do so without jeopardizing projects that are already underway.

Another possible approach on the additional rating category would be to give some form of regulatory reform to lenders who engage in activities above and beyond their traditional assessment area requirement to include efforts in other underserved areas. Currently, if a bank does not meet its CRA obligation, a regulator can use this as a reason for holding up the lender’s applications for such things as opening a branch. This threat of punishment is meant to incentivize lenders. What about possibly speeding up the regulatory process if a lender goes above and beyond in their efforts to serve the underserved? While the opportunity to earn an additional, more select CRA rating might not alone be enough to incentivize a lender, regulatory relief may help.

This is just a small sample of ideas on how the CRA’s assessment areas might be updated. There are many other issues, ranging from what is considered a CRA-acceptable activity to what type of test will be administered. While alleviating regulatory costs and improving clarity and efficiency are important, changes to the CRA should not compromise its effectiveness. The CRA needs to increase its rural success stories, like the $1.1 million expansion project for the Coastal Kids Preschool in the rural town of Damariscotta, Maine. Bath Savings bank earned CRA credit for its financial assistance of the project and these efforts meant more opportunities for daycare in an underserved and remote part of Bath Savings banks’ service area. While these stories may not be common today, such examples show that they are possible.

CRA has a more than 40-year history of expanding access to credit to low- and moderate-income communities. Banks have invested over $20 trillion in neighborhoods that were previously excluded by financial institutions before the CRA. If CRA regulations can be recrafted to incentivize additional investments in the still underserved and economically distressed communities, many of which are rural, the next 40 years will look a lot brighter for millions more Americans and the nation in general.

Comments