Dragtivists Edra Valencia, Aeon Mavis York, and Lolita LaVey perform at the “Soñamos Juntos” event. Photo by Veronica G. Cardenas

Photo by Veronica G. Cardenas

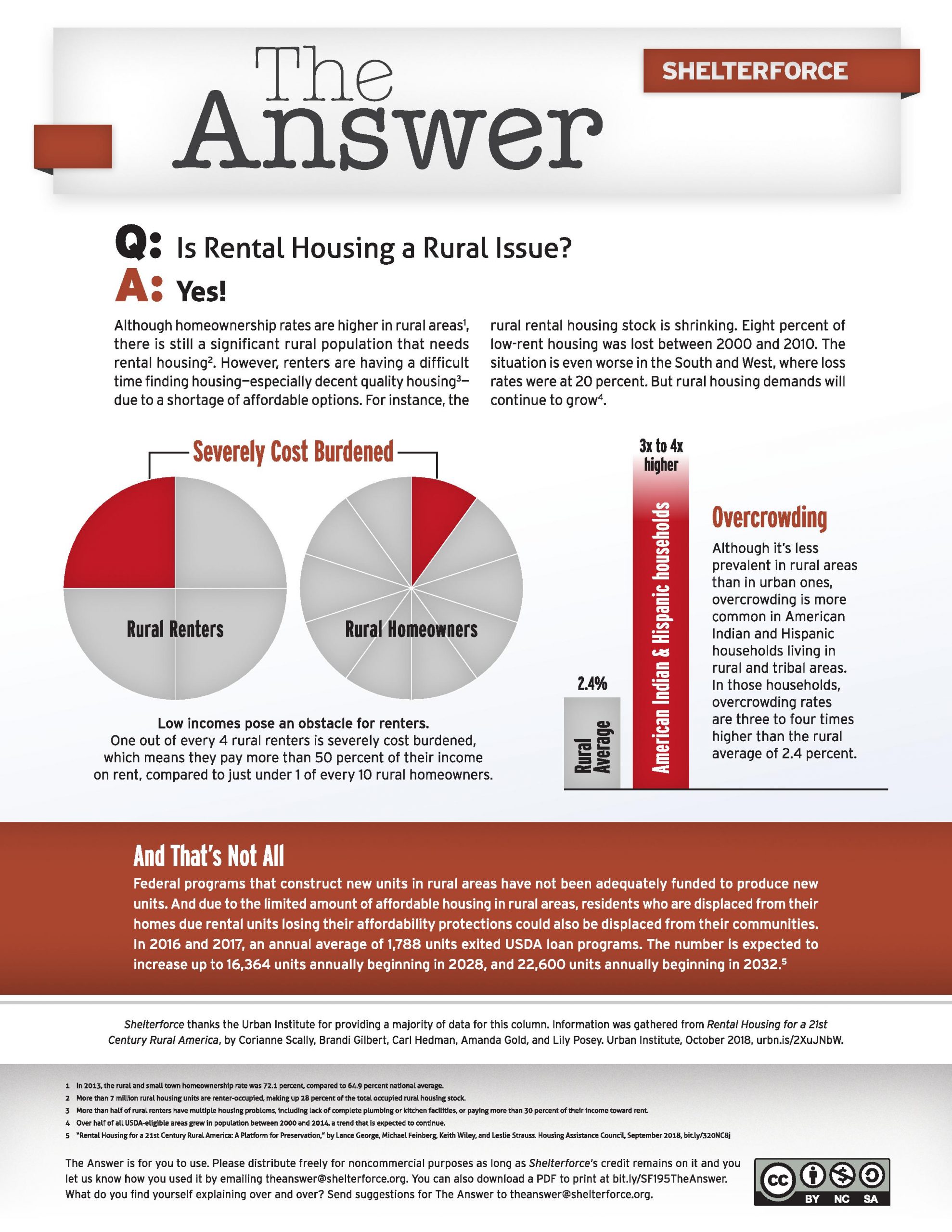

One of the poorest cities in the country is in South Texas, adjacent to the Mexico border. In Brownsville, the average annual household income is $15,030, according to the American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates from 2013-2015. The Rio Grande Valley region, however, is rich with the cultural history of immigrants. More than 90 percent of households identify as Hispanic or Latinx, and many families are mixed status, meaning one or more family members are undocumented.

Finding affordable housing is difficult in Brownsville. The occupancy rate for affordable housing is near 99 percent (the ideal rate for a city of comparable size is 95 percent), and since last year, the public housing program has been at capacity, with an average wait time of 2 to 4 years. With efforts underway to revitalize the downtown area, and new industries like SpaceX making the region their home, it could become even more difficult to find affordable housing in the city. All the changes make it clear that it is extremely important for Brownsville residents and civic leaders to take a hard look at what equity in the city would and could look like.

At Las Imaginistas, a socially engaged art collective working along the U.S./Mexico border, we focus on a variety of community development issues including development of microeconomies and the inclusion of community voice in regional planning processes. As recipients of a national socially engaged art fellowship called A Blade of Grass, Las Imaginistas worked on a 12-month community engagement program in Brownsville called Hacemos La Ciudad (We Make the City).

Divided into five phases, the program worked with city leaders, nonprofit partners, and community members to imagine the future of equity in Brownsville. Throughout the project we encouraged participants to play with time. Instead of telling residents to imagine Brownsville in 5 or 10 years, we asked them to imagine equity at any point in the future. Some of the proposed solutions could happen in three months, others would require 10 years. We designed the prompt this way so people would not feel tethered by the logic of whether something seemed achievable, but instead focus on strengthening their ability to dream the futures they hoped for.

Each phase of the project focused on a different way of knowing: The “Head” phase centered on verbal and cognitive knowledge. This stage featured lectures on the history of inequity in Brownsville. After each lecture, participants engaged in charrettes and small-group artistic reflection activities. The “Hands” phase focused on spatial knowledge. Participants were asked what a more equitable future looks like and then built it using household items and handmade building blocks. During the “Body” phase, participants imagined themselves as anthropologists of the future. They went through a number of guided exercises and used somatic knowledge to imagine what embodied equity felt like. In the “Voice” phase, actors collaborated with community leaders to write scripts about how they would solve problems in a more equitable version of their city. These scripts were then shared with the public through a series of site-specific performances in front of the border wall, at a community center, and on the lawn of a vacant house.

Lastly, information from all of these phases coalesced in the “Heart” phase. Using the reflections gathered from the public during the entire process, we created a three-part plan for civic art and equity, as well as a scale model of a more equitable Brownsville, which was presented to city officials, thought leaders, and community members. The plan will be a living document; it can be amended, adapted, and implemented in focus groups, city council meetings, and exchanges with elected officials to advance community accountability.

Reflections

The inspiration for the project began at a rally against SB4, an anti-immigrant show-me-your-papers law that instilled great fear in our community when it passed in 2017. At the rally we saw incredible leadership from women, activists, young people, and parents, some speaking Spanish, people we had never seen in appointed or elected positions. We were inspired by their clear vision and wanted to understand how their voices could be better heard at the city level, and how city-planning processes could better reflect the wisdom of the community.

After the rally we invited a handful of participants to a listening, healing, and dreaming session where we shared community concerns, took foot baths, shared homemade sweet bread, and using a sketchbook, pastels, and colored pencils, drew our visions for a city that better reflected the dreams of the community. Based on this listening session we designed the yearlong program for Hacemos La Ciudad. The purpose of the project was to make city planning more relevant to communities that are normally excluded from it and to present the ideas of the community to the city in a way that demonstrated the people’s strength, wisdom, and ingenuity.

A close-up of the model of a future Brownsville, part of the Plan de Arte Cívico del Pueblo (The Civic Art Plan for All the People). Photo by Veronica G. Cardenas

Over the year that followed, Las Imaginistas produced 10 events and engaged roughly 300 people in the process of imagining the future of equity and justice in the city of Brownsville. Through bike rides, serenades, Dragtivist (drag queens who are also activists) and site-specific performances, Las Imaginistas guided Brownsville residents in reimagining how they could influence equity and justice in their city. For instance, at an event called Practicamos El Futuro (We Practice the Future), students, activists, and religious leaders staged a performance in front of the border wall in which they imagined how our nation might reframe its relationship to boundaries and restore its connection to the Rio Grande (the Texas river that divides the U.S. and Mexico, which is not visible in Brownsville because of the wall). During the event, a woman imagined a future in which females fleeing violence in their countries are welcomed into the United States. Another person imagined that the border wall would be removed and the river would become a healing space for the traumas caused by the overpolicing of immigration.

As part of Hacemos La Ciudad, Las Imaginistas pulled in new ways of engaging the community and broadened the type of information that’s considered worthy of collecting. Community members communicated their planning ideas through movement (dance), sculpture (model construction), speculative fiction (performance), and conversation. Instead of relying only on the verbal skills traditionally employed in planning processes, we expanded the sorts of intelligence that are usually thought to be useful to include somatic, spatial, social-emotional, and narrative. We did this so that city leaders could use new methods for future community engagement.

As artists we think a lot about how space defines and influences our beliefs, attitudes, actions, and relationships, and how the built environment influences or discourages equity. We consider not just the objects around us but how their arrangement enacts silent scripts upon individuals and communities. An example of this is how Brownsville’s founding and militarization impacts its built environment. As with many other border towns, Brownsville’s history of colonization is reflected in its architecture. Some of the region’s oldest existing buildings were built to claim territory and impose ideological, cultural, and aesthetic dominance over previous land inhabitants including indigenous and Mexican people. Current initiatives to preserve these longstanding buildings reify the aesthetic dominance of European values while erasing the legacy of the land and region prior to its colonization.

At the onset of our project we wondered how—in a heavily militarized border town whose modern history centers on the colonization of the region—inequity might be built into the environment, and how community members could intervene in these systems.

Non-hierarchical

Exchanges with city officials can often feel as if they are based on hierarchy. The city maintains all the power while the community member feels powerless. When marginalized communities are taught that their voices do not matter, they respond accordingly, often with apathy and distrust.

Dancers perform their interpretation of the future at an event called “Soñamos Juntos.” Photo by Veronica G. Cardenas

Instead of convenings that reified established power hierarchies (across profession, race, income, education, nationality, gender, sexuality or language) we worked to disrupt those systems by designing spaces that valued different forms of civic expression. We facilitated activities in circles, positioned participants and facilitators as co-learners, and spent a minimal amount of time seated. When microphones were used, they were wireless and passed from one participant to another, instead of staying in a seat of power.

Dance exercises were used as tools for community planning. We partnered professors with elementary-age youth to co-design public spaces and used hair rollers as building materials for civic engagement and action. Our final model was built out of household items donated from community members, thereby disrupting the norm that architectural planning materials need to be pristine and expensive. These ideas co-existed seamlessly with the ideas presented by appointed and elected officials in the Plan de Arte Cívico del Pueblo Entero. The plan itself does not specify whether ideas emerged in lectures or in dance workshops. Instead it acknowledges that each person—at any time and in any space—can take an action to imagine and shape the city around them.

Deep listening

In exit interviews with the community, many residents emphasized how they left each of our program activities feeling heard, seen, and witnessed. During the “Hands” phase we facilitated a number of workshops in which people could create representations of buildings and services that they thought should be provided in a more equitable version of the city. Participants worked in small groups and shared their ideas with one another. One person wrote “Children’s Healing Hospital” on the back of a used CD and taped it on top of a pink jar. She said her child had been sick and there wasn’t a public hospital in the region to take her to. Children don’t have access to mental health resources, she said, so she combined the two needs into one building.

“People were actually asked what they thought, and it wasn’t just a one-time thing . . . it told people, ‘you do matter and we are still here,’” says Claudia Michelle Serrano, Las Imaginistas’ community activist and program researcher. Typically, a city has a town hall meeting to discuss a particular issue, and according to Serrano, that feels more like a strategy to defuse community dissent or to advance an agenda rather than genuine listening. “People had opportunities to say what they had to say. People felt that.”

Las Imaginistas is a socially engaged art collective that includes Celeste De Luna, Nansi Guevara, and Christina Patino Sukhgian Houle. Photo by Veronica G. Cardenas

Through our activities we worked to create environments where attendees had the opportunity to invest in their ideas. At multiple events throughout the “Head,” “Hands,” and “Heart” phases, participants contributed ideas by writing responses to open-ended questions pinned up on butcher paper and poster boards throughout the room, reflect on their ideas through facilitated small-group discussions with other participants, and then make a work of art in response to the ideas they explored.

During an event called “History of the Land,” there were a series of short lectures on the history of undertold narratives in the region. Tribal elders from the Carrizo Comecrudo Tribe and professors from the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley told stories of genocide and racial violence in the region. In another event these same participants used what they learned to draw a future Brownsville. One of the ideas that emerged was a place of healing to address the region’s violent history of colonization and as a place to process the current trauma that arises from being a heavily militarized region. Another group imagined a bi-national cultural and performing arts center, with amphitheater seating on both the Mexican and U.S. sides of the river banks. Both ideas were embraced by later participants of the program and eight months later were built into a scale model that represented the future of Brownsville. Those ideas were also incorporated into the final recommendations.

“That is what makes a difference in equitable power: shared power. When someone really listens to you, you want to contribute and show up because you can see how you make a difference and how someone else is valuing your contributions. That is really important in a place like Brownsville,” says Serrano.

Accessibility

One of the most important things we did was make sure we gathered a diverse group of attendees. We thought about what the community would receive from their attendance and how they would benefit from donating their time instead of thinking about community planning engagement as extractive, i.e., residents will provide answers needed to finish this project.

Accessibility is key. Language barriers must be eliminated (all meetings and all materials must be translated), stipends should be provided in rural areas to cover the cost of gas or public transportation to meetings, and childcare should be available.

Dancers perform their interpretation of the future. Photo by Veronica G. Cardenas

“I was most surprised by how radical [it] got,” says Serrano. “I knew once Beatrix Le Strange (a drag queen and activist) got involved, and community members [were] together in a room who would not have normally, and they were OK with it. No one was judgmental.”

It was important to have art as part of this process because participants got to see things that would never happen otherwise: the cultural magic and wisdom of the region being accessed as a superpower for civic change. During the final event, Soñamos Juntos (We Dream Together), the conjunto band Chuy Zuniga y Los Tres Hermanos led marchers down a street in historic Brownsville, just blocks away from the federal court house where family separations occurred throughout 2018, and down the street from the scene of the Brownsville Affair, a historic incident of racial injustice. For this event community members, activists, and appointed officials from the city joined together in a parade where participants chanted a call and response in Spanish. “Who are we? We are guardians. Guardians of what? Of our dreams.”

“The project became one of the community’s dreams: a group of people marching down the street [chanting] ‘The city is ours’ is so radical,” says Serrano. “The Latino consciousness is one that is always told you need to be proper all the time, and in that parade we claimed our right to shape the city.”

Next Steps

Throughout the year of Hacemos la Ciudad, participants engaged in activities in the streets of Brownsville, in abandoned buildings, in public parks, at the library, in artist studios, and at landmark locations. The program was not just a process in imagining a future of equity in our city, but was also embodying it.

The project culminated in the production of a three-part civic art plan inspired by the work of more than 300 people who contributed their voices throughout the project. The plan was made for three different audiences: civically engaged residents, thought leaders, and city officials. This structure was motivated by the idea that the power to advance equity does not lie solely in the hands of any one group, and that all three groups must work together to make lasting change. The Civic Art Plan for All the People (Plan de Arte Cívico del Pueblo Entero) was distributed to the public and city officials at the final event.

Each part of the plan had a primary directive and a distinct visual language. “Body” used highly saturated colors and silhouette cutouts to provide key information, based on participant input, on the importance of self healing in the work for equity and justice. “Thought” played with the visual language of cartography and astronomy. The instruction for this part of the plan was to cultivate your imagination and build community through the process of dreaming. Finally in “land” we used bright photos and maps to tell the story of the project and the key conclusions of the community. The directive for this book was that the city’s primary job is to listen deeply and regularly to the community. The plan was displayed in downtown Brownsville for one weekend in May and over 100 copies were distributed to attendees of the exhibition. (Copies of the plan can be accessed and downloaded here.)

In the years to come we will host reading groups for the Plan de Arte Cívico to determine the most pressing ideas and develop committees to advance them. Though the Plan de Arte Cívico has already been printed, we imagine Hacemos la Ciudad to be an iterative and living process. The work and ideas of the project will live through the continued actions and ideas of program participants and also in the continued permutation of the program pedagogy as we play with the ideas we explored throughout Hacemos in new contexts. Already one of the program suggestions, the creation of an immigrant welcome center in the city center, has become a topic in city elections: a local NGO group included it as part of candidate polling asking, “Would you support the creation of an immigrant welcome center?” More than half the candidates answered yes.

Comments