Kids stand in front of a mural in Thomas, West Virginia. A vibrant arts scene coupled with sustained creative placemaking efforts within the community have brought economic stability to an area once dependent on mining and logging. Photo courtesy of the Housing Assistance Council

Participants in HAC and [bc’s] Creative Placemaking peer exchange in Thomas, West Virginia. Photo by Omar Hakeem,buildingcommunityWORKSHOP

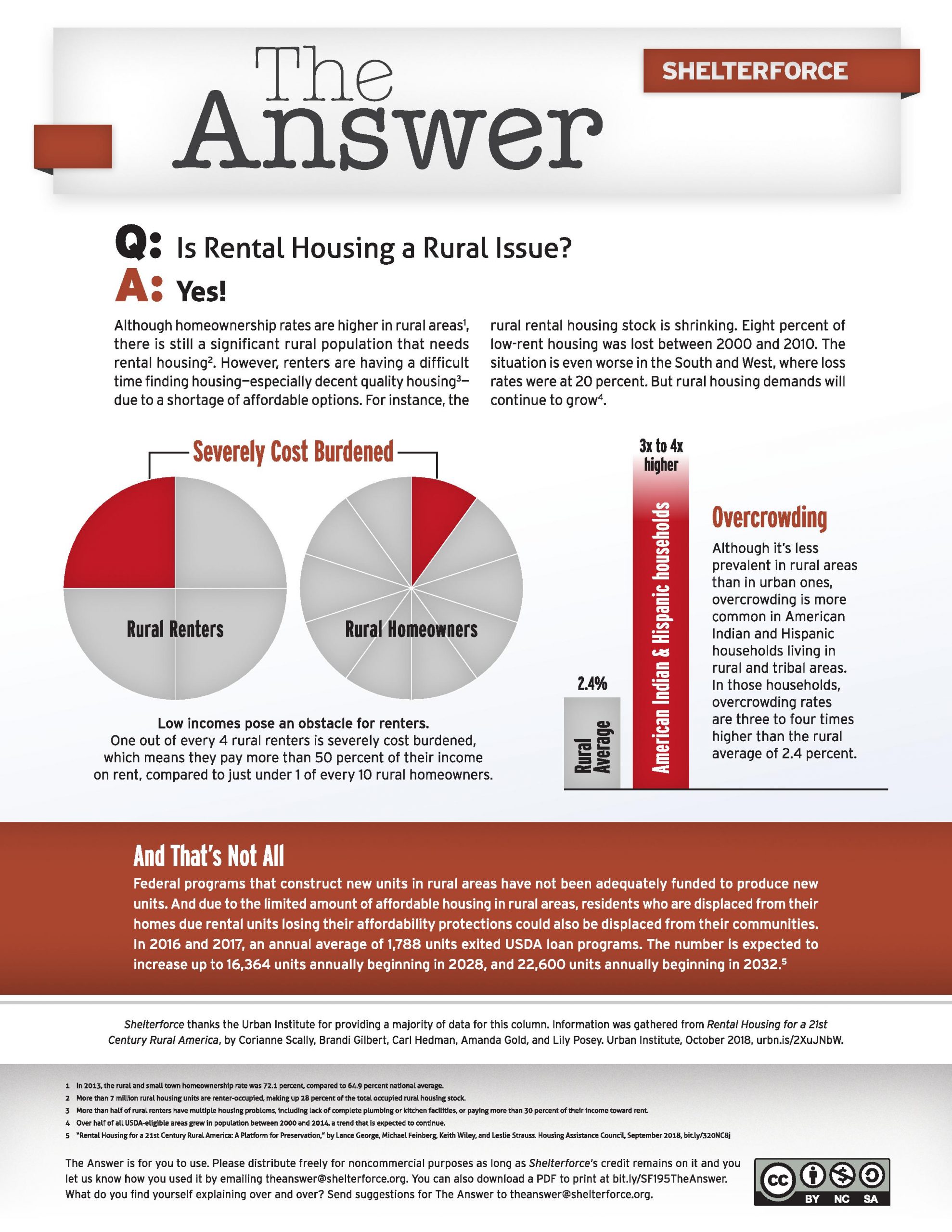

As a rural sociologist who works at the Housing Assistance Council (HAC), a 48-year-old organization that is focused on lifting the rural poor and understanding rural America, my colleagues and I are keenly aware of the national buzz that surrounds the rural condition. Such buzz is a double-edged sword. We want conversations rooted in reality; data matters, even when it isn’t pretty. But nuance coupled with an appreciation for rural tenacity is also a requirement for addressing and understanding rural America’s condition.

A sampling of negative news headlines I’ve collected attests to the challenges in rural America: “Economic Expansion Eludes Rural America,” “The Lives of Poor White People,” “HUD: Housing Conditions for Native Americans Much Worse than Rest of U.S.,” and “A New Divide . . . An Urban Rural Mortality Gap Emerges.”

Against such headlines, there’s a reason why I’m smiling—a National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) initiative called Citizens’ Institute on Rural Design (CIRD). In a nutshell, CIRD’s goal is to enhance the quality of life and economic viability of rural America through planning, design, and creative placemaking. The NEA selected my organization as its new partner for the initiative, which will allow HAC to foster rural design, planning, and citizen participation on a national scale, all while complementing our core mission of improving conditions for the poorest and most rural places.

Here are six reasons why CIRD is the perfect antidote to the negativity that permeates rural America.

- buildingcommunityWORKSHOP, usually referred to as [bc], is HAC’s partner in carrying out CIRD. The nonprofit is an award-winning community design center that partnered with HAC from 2015 to 2017 to take a look at how arts and community building tools can be used in rural communities. An example of [bc] at work is its Rapido program, which provides immediate and affordable post-disaster, long-term housing solutions and innovate design to vulnerable populations. Moreover, [bc] understands that its success in rural America requires recognition of existing rural ingenuity and know-how. The organization might retain Ivy-League-trained staff, but I can vouch that they also appreciate (and not with a hipster’s sense of irony) local character and work in places like rural West Virginia, where Woodlands Development Group, a longtime HAC partner, is spearheading an arts and design-rooted community revival. Woodlands has tapped [bc] to coordinate planning on a workforce housing project that brings together public and private resources to meet a locally identified need. In short, [bc] brings design panache to CIRD along with enough grit to work and succeed in America’s poorest communities.

- CIRD and HAC are learning from tribal communities. HAC’s Evelyn Immonen penned Native American Creative Placemaking, a report that includes an interactive map of Native American placemaking and notes that these types of efforts offer Native people an opportunity to connect with their traditional ways of life. At the same time, Immonen also emphasized that placemaking was always known to Native Americans and that outsiders ought to recognize such. She is taking on a leadership role with CIRD, and the lessons she learned while working in indigenous communities align with HAC’s long record of standing with tribal Nations. The field of rural design has much to learn from tribal communities; CIRD will do just that.

- Design is at the big kids’ table. I came to HAC full of ideas about place-based efforts spanning education to housing and beyond. I had seen place-based and arts-rooted efforts revive schools and their communities, and hoped HAC could play a part in such efforts. My colleagues expressed warranted skepticism about HAC and the broader rural housing community wading in to creative placemaking and design as they’ve seen many a fad come and go. After all, core rural housing programs were (and are) under attack. But, as is often the case, HAC’s local partners, led by CDC of Brownsville, made the best pitch: “This arts stuff works,” they said, while encouraging HAC to partner with [bc] on a National Endowment for the Arts funded award. We’re glad we did. Quickly, we saw that a handful of our local partners were already leading the way in arts and design, often in communities of persistent poverty coupled with a strong sense of place. As Moises Loza, HAC’s then executive director, would point out as HAC waded into placemaking, a number of partners, especially in the Colonias, had been doing placemaking “long before it was called such. They had to,” he said, alluding to the dearth of resources and the need for on-the-ground entities to do “whatever needed done.”

- It’ll be citizen-driven (rural citizens!) Our partners know that design processes must be truly locally driven, from new farmers markets to assisting a tribe’s relocation as their land base shrinks. CIRD can bring outside resources like skilled architects and planners to local workshops, enhancing community conversations and action. Top rural and tribal practitioners and design thought leaders comprise a CIRD Steering Committee that will inform trainings and bring geographic breadth and wide professional expertise to the initiative. Communities selected for CIRD will receive months of follow-up capacity building and technical assistance, as we know that design processes are rarely linear and to expect the unexpected. Through all that, we will empower local organizations and individuals, providing a sounding board and contacts with rural peers to share best practices, and helping to find additional funding opportunities. Rural people know their context, strengths, and challenges better than anyone else. CIRD builds on that premise.

- CIRD is co-locating top designers and planners with HAC’s experts in rural policy and rural programs. The National Endowment for the Arts support of CIRD is creating a collaboration space at the intersection of rural and design. This means that members of [bc]’s design team will join HAC’s rural development and rural policy experts in a common space. And we will invite fellows, local practitioners, and other designers to share as well. We are confident that this collaboration will spark new ideas and energy in our respective fields with rural communities as the ultimate winner when this happens.

- Philanthropy has (another) chance to support what works in rural America. Those who work at nonprofits love our funders and HAC is no different. At the same time we point to American philanthropy disproportionately favoring urban projects. HAC notes the intertwinement of rural and urban fates along with successes (driven by philanthropy) in linking urban and rural. By boosting rural design and leveraging the collective commitment from the National Endowment for the Arts and HAC, foundations and financial institutions can bring the best of rural design to more places, perhaps earning some CRA credits in the process.

The previously cited headlines lamenting much despair in rural America are daunting. The Citizens’ Institute on Rural Design alone, of course, is a drop in the bucket against long-simmering rural challenges. But it might be a drop with wide ripples, and that fuels HAC, [bc], and our partners. Check back in a year or two; I believe that quality rural design fueled by CIRD will be giving many more with a stake in rural America reasons to smile.

Comments