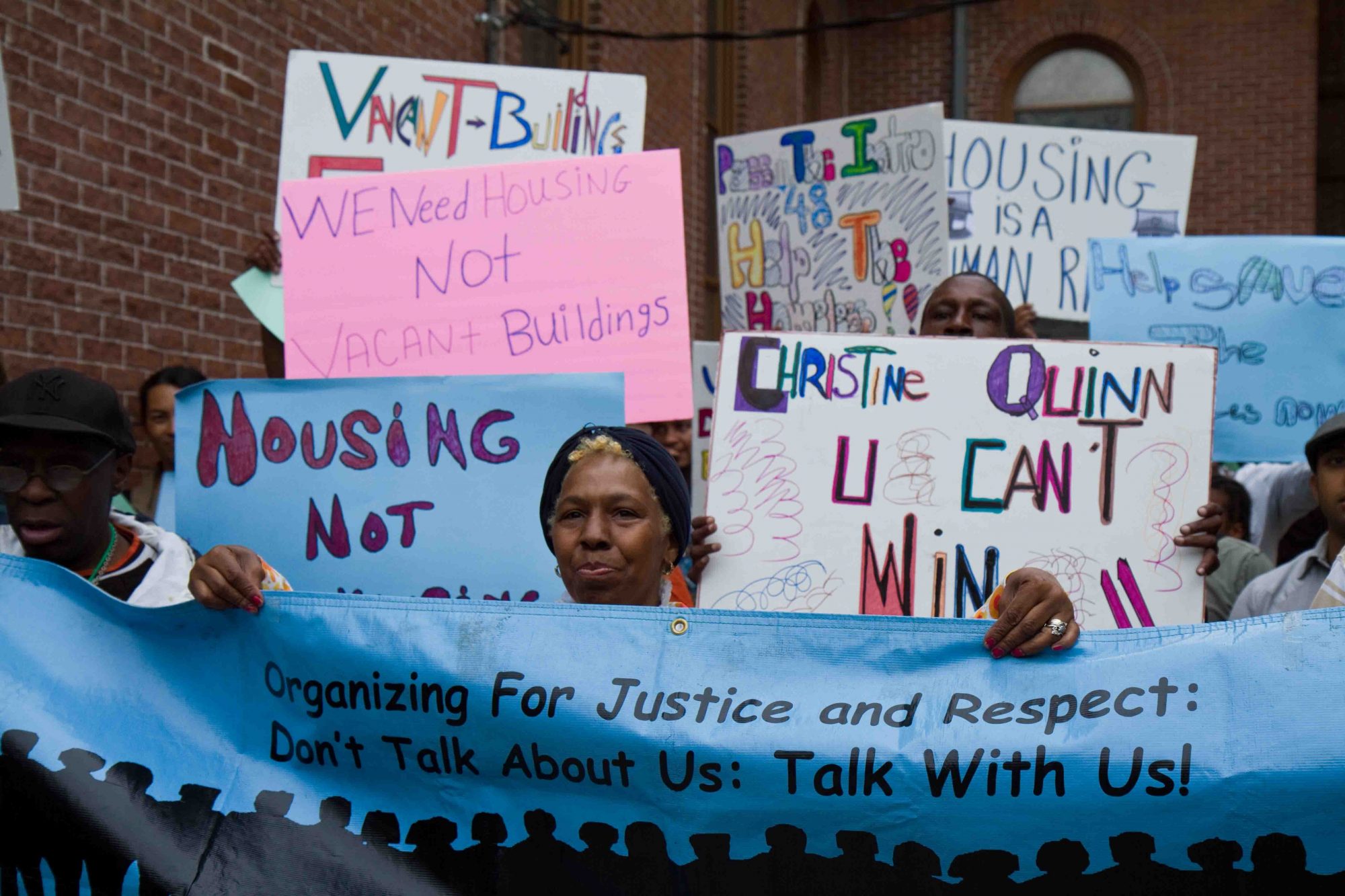

Members of Picture the Homeless protest outside council Speaker Christine Quinn’s office after she blocked an anti-warehousing bill in 2010. Photo courtesy of Picture the Homeless

A vacant building that Picture the Homeless documented in 2004. Photo courtesy of Picture the Homeless

In 2004 when homeless people started to put together a campaign to fight for housing policy reform in New York City, there were a lot of directions in which the movement could go. After all, there are hundreds of laws, policies, and practices that contribute to people losing their homes, or make it impossible for folks to exit homelessness.

Members of Picture the Homeless, an advocacy group that fights for New York City’s homeless population, mapped out a lot of those problems. Those included the city’s failure to provide housing for youth aging out of foster care, insufficient Section 8 vouchers, restrictive New York City Housing Authority policies that prevent people from getting on the waiting list for public housing if they have low-level “quality of life” violations, and the fact that the Bringing America Home Act—a bill that aimed to end homelessness—was before Congress.

Any one of these issues could have been the main focus of a major campaign. But the thing that quickly rose to the top of the list—the issue that, if addressed, had the biggest potential to make real systemic change—was property warehousing. Buildings in the city were kept empty because it was more profitable for owners to hold onto them as investments and sell or renovate them when the surrounding neighborhood gentrified. Some were brownstones in need of significant work, but many were mixed-use tenements that we knew must be structurally sound because there was active commercial space on the ground floor, though the residential units above were boarded up. We called a broker whose number was listed on the window of a for-rent storefront and pretended to be interested in renting it. We asked if there were plans to rent the upstairs units, and the person said, “Don’t worry about that, [the owner] makes enough money from the storefront that he doesn’t need to have the headache of tenants.”

As property values skyrocket in historically low-income neighborhoods, it becomes increasingly profitable for owners to hold residential units vacant. The math is simple, and brutal: a short-term loss of rental income by not accepting tenants paying a neighborhood median of $800 (which would be locked in for these predominantly rent-regulated apartments, whose tenants would then be extremely difficult and costly to displace) is outweighed by the long-term gain of holding out for tenants who will be able to pay $2,500 a month.

It’s the same math that sees landlords raising rents every year as wealthier new arrivals colonize formerly impoverished areas, until the existing residents of these neighborhoods—historically and primarily people of color—have no options. That’s one reason that, according to the city’s own data, over 89 percent of homeless families in New York City shelters are Black and/or Latino, and why the same neighborhoods of color where gentrification has hit hardest also have the highest quantity of vacant buildings and are sending the majority of homeless people into shelter (as per data from the Citizens’ Committee for Children).

Never mind that tens of thousands of people were sleeping in city shelters, and untold thousands were out on the streets—owners could refuse to rent the apartments in their buildings, and there were no laws to stop them.

Homeless people knew that wasn’t right. And they knew that it could be changed.

But when members of Picture the Homeless started speaking with elected officials, we got blank stares and complete denials that property warehousing still happened. Even other housing advocacy organizations told us “that’s not a problem anymore,” or that because the city was no longer the primary owner of these properties, there was nothing that could be done about it. Real estate is king in New York City, and politicians would never try to tell landlords what they can and can’t do with their properties.

“Why are these buildings empty?” asked Picture the Homeless member Rogers when we met with the commissioner of the Department of Homeless Services. “That landlords can hold on to empty buildings in the hope of maximizing profits, without contributing to the public welfare of people from the communities in which those buildings are located is a major scandal. We want landlords and our elected officials to promote community need over corporate greed.”

Faced with a widespread, erroneous belief that warehousing was a thing of the past, the first thing our members decided to do was prove that it’s still a problem. So we started counting the vacant buildings. When we found enough to show warehousing was a real problem, we got then-Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer to collaborate with us on a block-by-block count of vacant buildings and lots in Manhattan. In 2007, when we had found enough potential housing in existing buildings and on buildable lots for 24,000 households, we got a city council member to introduce anti-warehousing legislation.

Our legislation was bold, big, and combined several of our members’ main demands: counting vacant property, identifying landlords, criminalizing warehousing, and moving money away from the bloated, expensive shelter-industrial complex to fund housing for homeless people.

The proposed legislation was also completely doomed.

The council member who introduced the bill was notoriously bad at getting legislation passed. Council members routinely defied their colleagues and the rules of legislative etiquette. It was great that our council contact was willing to introduce a piece of truly revolutionary legislation, but introducing something doesn’t mean a thing if it won’t go anywhere.

For our members, it was a steep and brutal learning curve. Politicians don’t typically spend a lot of time listening to their homeless constituents. They don’t follow the normal legislative process we all learned in school, and learning about the behind-the-scenes factors that slow down even the best of bills was frustrating to us.

So we learned to compromise. We identified which council members had the political acumen to actually get something passed. We met with them and found a champion for our bill. Homeless people brainstormed the most strategic first step, to shift the conversation toward criminalizing warehousing, and they decided to start with legislation that would force the city to conduct a count of vacant buildings and lots. Once we could shine a spotlight on the role that warehousing played in the housing crisis, we felt confident that we could galvanize public support for more aggressive solutions.

Easy, we thought. Who could be opposed to simply counting property?

Members of Picture the Homeless count vacant buildings in New York City in 2011. Photo courtesy of Picture the Homeless

As it turns out, lots of people. Backroom bureaucrats held the bill up for years of fruitless meetings and unreturned phone calls about “definitions of vacancy” and “information sharing” between city agencies, or inaccurate declarations that our proposed bill conflicted with another bill that already had been introduced. Later we learned that the council was “getting pushback” from then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg, who was allegedly concerned about the cost of the bill. Our members were outraged to learn that council technocrats had been sitting on a bill just because the mayor didn’t like it. We had been under the impression that the council existed as a counterbalance to the mayor’s power; instead they were killing every bill he had “concerns” about.

When we tried to get council members to move the bill forward, they refused. We played nice and it got us nowhere.

So we played not so nice. We disrupted city council hearings, chanting loudly, and were dragged out. Picture the Homeless members and staff, even ones who had nothing to do with the disruptions, were unconstitutionally banned from public meetings by Council Speaker Christine Quinn. We organized a “sleep out” protest at the district office of the chair of the Council’s Housing and Buildings Committee, letting all his constituents know he was refusing to respect the legislative process. As a result of that action, the New York Post wrote a series of inflammatory race-baiting articles about us, alleging that we used the sleep-out to train sex workers and drug dealers on breaking and entering, which was widely picked up on right-wing websites and white supremacist forums. Those articles led to countless hateful phone calls and emails to our office, and to Speaker Quinn stripping us of $50,000 in funding, even after an official investigation by the city agency that funded us found no evidence of wrongdoing.

Eventually, we got smarter. Being part of the landmark coalition Communities United for Police Reform taught our members a lot about how to get a bill passed, resulting in the 2013 passage of the Community Safety Act. Applying the lessons we learned there, like keeping the conversation positive, being patient with the process, meeting with every council member to educate them about the bill, using social media to build a buzz around the issue, and broadening our coalition work, we were able to get the bill reintroduced in 2014 as the Housing Not Warehousing Act. This time around it, the legislation was even stronger, with three separate bills that would force the city to count vacant property, identify specific properties that could be used to create housing for extremely low-income households, and create a registry and make owners pay a registration fee for each vacant property. In March, the city released findings from its Housing Vacancy Survey and found there was a large increase in the number of vacant units not available for sale or rent, from 182,600 in 2014 up to 248,000 in 2017. “The number of vacant units not available for rent or purchase is more than all the new housing units created from 2014 to 2017,” according to the Association for Neighborhood & Housing Development.

We made hundreds of calls to council members, went to dozens of meetings, developed talking points and a social media strategy, and held Twitter rallies and got #HousingNotWarehousing trending. We led walking tours and “vacancy visioning” sessions for community members to learn about the wasted space in their neighborhoods, and discussed what those spaces could be developed into.

We know this is not the end of the road. Property owners still have all the power in this equation, and if they want to keep their properties off the market, we still don’t have tools to stop them. But shining a light on one of real estate’s best-kept secrets, a crucial aspect of how the housing market keeps supply low and demand high, can help show New Yorkers that this is a significant and unacceptable practice. Proving that it’s a problem will change the conversation, and push the boundaries of what is politically possible.

Homeless people fought to ensure passage of a bill in 2017 everyone said would never pass. Picture the Homeless changed the city charter forever. We showed the city that homeless people are a force to be reckoned with.

“Maybe we made a lot of mistakes along the way,” said Picture the Homeless member Andres Perez. “But we kicked a lot of ass too. I’m still stunned that this finally happened. It’s a beautiful moment.”

Warehousing is a national problem that’s happening in the San Francisco Bay Area, Seattle, Vancouver, and London, just like homelessness. In fact, the two are inextricably linked. Both are consequences of a market system that prioritizes property rights over human rights.

“The 2010 census revealed 18.6 million vacant homes nationwide,” said one member of Picture the Homeless back in 2011. “There are an estimated 3.5 million homeless people. That’s about five vacant homes for every homeless person.”

Comments