Michael Bodaken. Photo courtesy of the Sallan Foundation

Shelterforce has worked with Michael Bodaken, the longtime director of the National Housing Trust (NHT), pretty much since he came to the organization. He has written nearly a dozen articles for us, as well as provided ideas and perspectives along the way. We took the occasion of his retiring from NHT to speak with him about how he got into housing, some of his favorite projects, and his recommendations for the field going forward.

Harold Simon: So, who are you, how did you get into this, and why didn’t you become a stockbroker?

Michael Bodaken: Some 30-plus years ago, almost 40 years ago, I started out as a tenant organizer in Topeka, Kansas, as a [Americorps] VISTA, organizing residents in newly built HUD-subsidized housing. After that, I was able to go to Los Angeles and became a public-interest lawyer specializing in slumlord activities and redevelopment activities for 12 years. I was lucky enough to be hired as the deputy mayor/housing coordinator for Mayor Tom Bradley.

And then, Mayor Bradley decided not to run [again]. I applied for a California Housing Partnership Corporation (CHPC) position. In the middle of the interview, [CHPC founding CEO] Helen Dunlap said, “You know, you’d be perfect for the National Housing Trust.” I took that two ways. One was they didn’t want to hire me for the California Housing Partnership, and the other was I should check this out.

When I came to the Trust, there were no employees. I came here some 25 years ago for one year to turn it around. And the joke I like to tell is I never quite got it right, but I almost got it right.

The compelling piece of why I wanted to do this was that it merged my interest in combining policy and practice. That was the explicit mission of the Trust.

I actually didn’t know a lot about finance when I first came to the Trust, but I learned over time the value of understanding finance and how understanding finance could lead to more concrete, executable policy recommendations that made sense on the ground.

Miriam Axel-Lute: You said that getting into knowing finance can make policies better. Can you think of some of the top examples over the course of your time at NHT where you’ve seen policies that you were either able to advocate to make better, or thought clearly you knew how they could be made better because of your finance understanding?

Bodaken: There was a person named Charlie Herrick at the National Consumer Law Center who published a pamphlet about seven years ago, “Up The Chimney,” which castigated HUD for not making public housing and assisted housing more energy-efficient. At the time, HUD was spending over $7 billion, 20 percent of its budget, on utility costs.

I read that, and I thought, “My God, that’s terrible,” and I had the smarts to call him and say, “Come on down to D.C. I want to learn how to understand this, and I’ll pay for your trip.” In Massachusetts, Charlie was working with utilities to fund housing redevelopment, rehabs, making housing more energy-efficient. Owners liked it, residents, everything was great. We took that idea to 12 other states and uncovered over $300 million that wasn’t previously there, private funding that is now available to owners who want to redevelop their properties. I just read last night that some six or seven states are now using that funding in how they do pro formas for their tax credit properties when there’s a rehab.

In Minnesota, housing finance agencies are making the owner go to the utility first so that public resources can go further. The Trust took our platform, [and] worked with others to do something that no one else was thinking about, because they weren’t thinking about private funding.

I am [also proud] that the Trust has been able to protect project-based funding for Section 8 through thick and thin over the last 20-plus years. In the 1995 budget, the Clinton administration said they wanted to voucher out the entire project-based subsidy that affected over 1.4 million seniors and families.

We wrote this fundamental critical piece making sure that people understood that once you vouchered out the stock, you wouldn’t be able to finance it. The great quote we used then was that vouchers are necessary but not sufficient for any rational housing system. You want to absolutely give people the power to find places with vouchers, but if you want to redevelop housing, if you want to have dedicated affordable housing on any kind of scale, you have to have some kind of finance that is based on the project, not the individual.

So we mounted this campaign, and ironically, we were able to find Western senators, Sens. Bennett [and] Craig, a couple of other Republican senators who had significant subsidized housing in their states, and we were able to turn that around. That was not easy.

Simon: Did you have allies in that battle?

Bodaken: Absolutely. The Preservation Working Group was fundamental, plus there were a bunch of for-profit developers and owners who were represented by the National Leased Housing Association. I enjoyed doing that because that drew on my political background and also drew on my beginning to understand how important housing finance was.

Axel-Lute: How would you describe the role of the Trust in the national landscape of affordable housing advocates?

Bodaken: I think it’s fair to say that I know of no other national nonprofit that has also had housing ownership. We own and operate 5,000 apartments. We helped others develop 25,000 apartments. We have a lending institution that makes loans to nonprofits all over the U.S. to help do affordable housing preservation. And we have a very strong state and local advocacy team.

And that is, I still think, relatively unique. Enterprise comes closest to it because they have a very strong lending team and a very strong policy team. But, until they just merged with CPDC [Community Preservation and Development Corporation], they didn’t really have any ownership. They syndicated tax credits, but when a project went belly-up, it wasn’t Enterprise who had to deal with it.

So, we took a leap of faith, really, into ownership well before, or beyond, what any [national] organization really did and used that as a lever for our policy prescriptions, so that our policy, when we went up to the Hill, we weren’t just a policy organization that didn’t have any experience in the real world. We owned properties in 12 states and the District of Columbia. We made loans in 25 states. And that doesn’t mean that pure policy advocates are wrong or anything, but I’m just saying that gave us a certain distinction that I think is unique for certainly D.C., and probably the U.S.

Simon: So, whatever year you made that decision in, you looked around, and nobody else was doing it. How come you actually did it?

Bodaken: I came in 1993. There were no employees. There was a little bit of money in the bank. I just took very literally the notion that we had to develop some kind of businesses to help make our policy more vibrant. It took about five years to get the lending fund situated, and it took actually longer than that to make it strong.

The truth of the matter is that Bart Harvey from Enterprise and I were sitting in the back of a cab at the Colorado Housing Finance Agency’s conference back in 2000, and we were both bemoaning how this portfolio of properties in Missouri had been lost to a for-profit developer. Bart was on my executive committee and he suggested that the Trust would be a good organization [that] could come in where properties were at-risk, especially at risk of loss of affordability, and try to grab the properties before the for-profit developers got there. There should be at least an option for those tenants. That was very attractive to me.

And so, I pitched that, and MacArthur [Foundation] had faith in that notion, and in 2001 we converted our technical assistance team to a real estate development organization. It took a while, but we decided we weren’t going to go in and step on toes. So, if there was a local organization that could handle it, then they didn’t need us, that was fine, but there were lots of places where the local organization wanted us to work with them, or there was no local capacity, and that was a great place for us.

HUD was putting out notices of where these properties were getting pre-payments, so we could search those notices for potential projects. It was pretty straightforward if you just put together a system.

We have over 1,000 units now in D.C. that wouldn’t have remained affordable had we not stepped in. Sometimes that’s with partners, including for-profit partners, or sometimes that’s on our own.

Axel-Lute: Do you wish that you’d grabbed more units in D.C. before the prices went up?

Bodaken: Absolutely. I mean, I don’t know that we could have. We only had a certain amount of capacity.

Axel-Lute: Right. And how do you balance the ability to do more units with the ability to keep them affordable?

Bodaken: Ford [Foundation], about six years ago, decided that community developers didn’t care about fair housing. Lisa Davis brought me into this room. The room was filled with fair housing lawyers and advocates and me. And the room made the case that the low-income housing tax credit and housing developers were not paying attention to areas of opportunity. This needed to change, and I needed to make that happen.

Over the next three years, community development organizations and national housing advocates and fair housing advocates tried to agree to a statement of principles. We came very close. I won’t go into the details, but it didn’t quite work out.

Long story short, at the end of that, I was very upset because I felt like just talking about it didn’t make a difference. So, I decided that we, the Trust, would use our resources to make it happen, and fashioned a housing-driven solution that would take into account opportunity but would not require new construction in areas that were really not zoned for this kind of thing.

Our High Opportunity Partner Engagement (HOPE) [project], is about two years old. We work with fair housing advocates and developers in five [areas], Minnesota, Chicago, Baltimore, New Jersey, and West Hartford, Connecticut. We’re buying market-rate properties proximate to good schools, as defined by the Great Schools Index.

We purchased our first property with Common Bond in Minneapolis. This is a [64-unit] property that never accepted vouchers. We’re going to have 14 families in there with vouchers in the next year or two. Those kids will go to elementary schools that score eight or above on the Great Schools Index. And they never could have had that opportunity.

We’re trying to market this idea to others, and there’s a few people out there kind of looking at this, but it wasn’t happening until we did it. Kresge finds this interesting. I think there’s a lot of general interest in the housing community.

The Trust has over $5 million in program-related investments which we’re willing to lend to others to do this kind of work. It’s hard for developers to think outside the box, but I’m beginning to see some developers talk to the Trust about it more. JPMorgan Chase has just funded a research grant with PRRAC [Poverty and Race Research Action Council] and the Trust where we’ll follow these budding initiatives.

The Trust is dedicated to this because we think it’s the right thing to do. We also think that at a time when tax credit pricing is going down, why not just buy a market-rate property, not a NOAH [naturally occurring affordable housing] property, if you can make the numbers work? Now, vouchers sometimes don’t work in those markets. But, we’re getting closer, and I’m confident that the Trust will buy a couple of these properties, and we’ll use that as a platform to urge others to do it.

Axel-Lute: And you’re getting affordability in there just by having them accept vouchers now.

Bodaken: Yes. So, we’re introducing new affordable options. One way to think about this is how long would it take to build 14 new affordable units that would take vouchers in Coon Rapids, Minnesota. The answer is “never.” That’s how long it would take, never.

And we are going to have, within two years without doing any new construction or going through zoning or any NIMBY, at least 14 units in Coon Rapids. That’s the basic idea, that you don’t have to deal with all this NIMBY bullshit; you just go around it and think about it in a creative way.

Axel-Lute: And are you intentionally shifting a certain percentage of the units to accept vouchers?

Bodaken: Yes, 20 percent or more. We’re not doing 50 percent because we don’t think that that’s realistic. We also want to make sure we’re sensitive to the neighborhood. We’re going in to try to show something can work.

Simon: You’re not evicting anyone. Are you waiting for unit attrition?

Bodaken: A very good point. Yes, absolutely. The attrition in these market-rate properties is over 14 percent a year, so it’s not an issue. Now, sometimes they’re one bedroom, and then we have to think through how that works because we’re trying to attract families. But, as long as we have one or two bedrooms, we’re probably in good shape.

Simon: That makes it easier for the NIMBY component, too, because it’s not all of a sudden. It’s just a gradual change that no one really notices.

Bodaken: Nobody’s going to really notice them.

Axel-Lute: I suppose while you’re at it, you’re also able to keep the rents on your market-rate units in your buildings from going through the roof if things happen to gentrify as well.

Bodaken: Yes. I mean, we have to make the numbers work, and we have to repay everybody. We’re basically assuming a certain increase in the market-rate units that’s beyond the voucher rate units.

Simon: What’s the return?

Bodaken: It’s less than 6 percent. It’s a pretty low return, honestly, for a real estate investment where you’re taking a real risk. I wish we could say it was higher. Our equity partners are getting a higher rate of return, but they have more money in the deal than we do.

Simon: Once you described this idea to me a couple years ago I became an instant convert. Why didn’t anyone think of it before?

Bodaken: I will say it’s not easy to do, to be fair. One of the questions is how many of these deals can you really do, because they do take time. The Trust has hired someone just to look for these deals. Most developers wouldn’t consider doing that, right? It’s very different than the neighborhoods they typically operate in.

Simon: You mean nonprofit developers or for-profit developers?

Bodaken: Nonprofits. I think it’ll take some time. But I would put my money in these deals because they’re strong deals. They’re near strong schools. Even during a market depression, these properties are not going to go down that much, as long as the schools remain strong. And so, your level of risk is not as great as it would be in a property where people are losing jobs, or so forth. You have to just think about it differently. Everybody has to kind of set aside all their assumptions and say what are we really looking at. We’re looking at market-rate investment. As long as that market performs, the risk isn’t that great, so I don’t need a high return. It’s all about risk-adjusted return.

As interest rates rise, I am concerned about will property values correspond, and how long will that lag take. But, other than that, I’m not too concerned about this.

Remember, for Common Bond, who actually put in more equity than we did, they get management of a new property, so they’re going to get cash flow from the management. If you have a management company, it really makes a lot of sense.

I’m not a very good predictor. I tend to be pretty pessimistic about political outcomes and things like that. But there does seem to me to be kind of a rising; affordable housing is beginning to get back onto the agenda. I think you may know about this: Funders for Housing Opportunity.

Simon: Yes, NHT is one of their grantees this year, right?

Bodaken: Yes, we are. And that is so heartening to me, those funders, they are really in it for the long haul, at least they say they are, and I believe them. And if that’s true, then I think I can see during the next election, or during the next cycle, the ability to create a narrative that might, for the first time in a long time, put affordable housing on the same, or close to, footing as education and health and these other essential needs, and away from the notion that “the government provides housing, so it’s not really my issue.” For the first time in a while, I feel like there’s hope in that.

Simon: If you start bringing in allies like NRDC, it has a much more likely chance of actually getting on the agenda.

Bodaken: Yes. I’m sitting down with the Trust federal housing policy director and the NRDC, and we’re devising a federal campaign in which NRDC’s allies will get involved in housing.

Simon: That is so necessary, you’re just perfectly positioned to do that. That’s the really promising thing, when unlikely allies, people who’ve been kind of antagonistic sometimes, actually say, oh, we have common interests.

Bodaken: You put it in today’s Shelterforce [Weekly], why health and housing is hard to do. That was the headline.

You know what? You’re right. But that doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t continue to try to unlock this stuff. There’s a lot of synergy there. We know what the connection is. There’s not a lot of debate about the connection. So, if that’s true . . . again, it probably takes a while, maybe a decade, but that could be a very big thing for housing.

Simon: Yes. Building common interest among disparate allies is really the key to moving any big agenda item. Can I just go back the beginning? You gave us a very brief outline of your trajectory. Going back even earlier, how did you end up becoming a tenant organizer instead of getting a poly sci degree and going somewhere else?

Bodaken: So, I was a history major at the University of Iowa. That was in graduate school. And a professor of mine, Peter Larmour , who I loved, came up to me one night. It was a rainy night. We were inside University Hall, and he said, “You know, with a PhD from this fine institution, you could one day become a cab driver.” I took that to heart. The next day he gave me the U.S. history abstract of available jobs in the U.S., and I think there was one job, in Mississippi. And this was 1974 or 5. And he said, “You should become a lawyer,” and I said, “I don’t want to become a lawyer.” He said, “You should become a lawyer.” I said, “I don’t want to become a lawyer.”

All right, I was wandering around campus, and I saw a sign that said “Volunteers in Service to America,” and I walked up, and they said we have two openings for V.I.S.T.A. in this region. One is a consumer credit counselor in Lincoln, Nebraska, and one is working with Legal Aid Society in Topeka, Kansas, organizing tenants. I’d been an organizer a little bit in my radical days in the University of Iowa. And I knew Topeka was south of Lincoln. It had better winters. And so, I immediately chose Topeka, and that’s honest-to-God what happened.

That led to everything else. That decision led me to organize tenants, which I fell in love with. I worked on a campaign to do a tenant’s rights handbook. We were opening the Topeka Housing Information Center. It was just a very dynamic period.

Simon: Tell us more about where you grew up.

Bodaken: In kind of the furthest thing from a social justice/leftie household. It was a small, very small town in Northwest Iowa. My father sold trucks and farm implements. My mother was a housewife. We were kind of the standard middle-class family. I wasn’t brought up in a political environment.

I got to the University of Iowa in 1968. You talk about being formed by your environment, obviously that was the time when a lot of protests about the Vietnam War were going on, civil rights, and so on. And that shaped me starting probably in ’69, ’70 through ’74 or ‘5 when I left for Topeka. And during that time, I worked [with] a group called the Radical Student Association. There’s a very funny article that someone just unearthed from 1974, where I led a protest against a bar that was serving non-union wine. The owner came out and was putting a hose on us, and giving non-union wine to spectators, and I vowed to sue him. The sad fact of this story is that I didn’t remember it at all until someone sent the article to me. I still don’t remember it independently. I don’t know what that says about my memory.

Axel-Lute: Or partaking of union wine?

Bodaken: Yes, that’s right, I probably drank too much union-made wine.

Simon: So, I think you had said in an old Shelterforce, well, it was the ’60s, ’70s, and we were all radical, and we picked housing because that was just the thing to pick, and that was where we fell in, as opposed to a grand scheme.

Bodaken: Oh, yes. I felt like housing chose me. It was far from a grand scheme. But once I got hooked on housing, it was very clear to me what I wanted to do with my life. I was just very lucky that way, very, very fortunate.

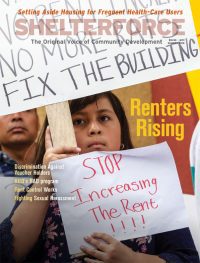

Axel-Lute: There’s a resurgence right now of tenant organizing and tenant advocacy. Do you have a sense of why we seem to be seeing more activity? It’s on the local level, but there’s still an uptick all around the country.

Bodaken: I think uptick is exactly the right word. I mean, obviously, economics and rents have a lot to do with this. There’s lots of data from the last State of the Nation’s Housing from Harvard, which shows that the affordable housing rental crisis is not just affecting poor or even low-income households, but is creeping up the income ladder.

And so, you have a more powerful constituency, and wider constituency, for tenant protections than you’ve had in prior decades. It’s still not Europe, but as people like my son have trouble figuring out how to buy a home, they become renters longer, and they take their rental rights more seriously than they would if they became homeowners. And so, as long as you have a decline in homeownership and a rise in rental households in the U.S., and have pressure on rents, there’ll be pushback, countervailing pressure for renter’s rights.

The thing to watch, and I think it is important to watch, is as rental demand increases, landlords have a stronger hand, at least economically, right? It’ll be interesting to see how this all plays out. To the extent these people are voters and they are able to exercise their fundamental rights, there will be more pressure for the laws to treat tenants fairly.

Axel-Lute: So, one of the benefits of doing exit interviews is that hopefully folks are a little more free to talk about things that they’ve seen that are going on in the field. What do you wish the affordable housing or community development field would do differently?

Bodaken: I think there’s still a strong tendency to do things as we’ve always done them, and to talk about programs rather than people, although that’s changing. I think it’s not changing fast enough. I think that’s the biggest problem that we have. In meeting after meeting, people talk about programs and statistics and don’t personify how it applies to people.

Axel-Lute: Do you think that’s bad in terms of our ability to advocate for what we need, or is it also bad for our decision-making?

Bodaken: Mostly the former. I actually think our decision-making isn’t too bad, but I think our ability to bring in allies and broaden our message and make it understood and heard is hurt because of the lack of an effective narrative. I’m not the only person who thinks that. We talked earlier about Funders for Housing Opportunity. That group is certainly looking at that. There’s a lot of people trying to change the narrative. But I think that’s kind of the most fundamental concern I have.

One of the things I think we’re doing very well, or much better, is thinking about how our work affects other fields, in particular education and health. We’ve talked about HOPE, High-Opportunity Partner Engagement. Just being able to work with civil rights organizations on affordable housing issues is fundamental, and I see a lot more interest in that. There’s a lot more emphasis on green and healthy housing. People understand what that means. It makes sense to them. As we bring in new allies who we can work with to defend their particular concerns, they can defend ours. And I think that’s essential.

Simon: What do you attribute that to? Why is that happening more now than 19 years ago?

Bodaken: I think it’s really a direct result of the attack on federal and state housing programs and people trying to figure out a way to make this work better understood, because they realize that the traditional allies, the old blocks of Democrats who supported affordable housing in the past are either retired, or they’re leaving.

As other causes have moved up in people’s minds, housing has moved down, and people realize that, and they’re trying to figure out how to view what they do in a different light, which I think is really a good thing. I don’t think it’s cynical. I think it’s very smart. And lots more funded research is going on demonstrating the tangible benefits to people’s health of housing, to the extent that the kids can be stable, even in poorer neighborhoods. Their education levels rise because they’re not moving frequently, things like that.

Simon: Well, where would you like to see the field it go in the next 5 to 10 years?

Bodaken: In general, what I’d like to see is more holistic financing, based not only on housing, but on health and energy efficiency, where people begin to correlate the benefit of affordable housing on people’s health and the environment, and potentially on education, and to open up new avenues for equity and debt for developers, for this to become kind of mainstream.

To the extent we can help major institutions, political institutions, understand the cost-benefit of financing housing for health, education, people’s general welfare, that’s more like what should be happening. Healthcare financing for housing is just beginning to be explored. Energy efficiency financing for housing is just beginning to be explored. But, it’s beginning to happen. That’s the future. That’s where I’d like things to go.

Hello Michael! Great memoir and shout into the future. And congratulations on running the race well, with “semper fi” for the cause, all these decades. I am but two months retired after 39 years at the FHLBSF but remember those early days and meeting and working with you when you were with Tom Bradley. And thanks for the chuckle in recalling your referral to the Trust, done in a way only the inimitable Helen Dunlap could! Good fortune and future…And thanks Harold and Miriam…

Hi Michael, congratulations on your retirement. Take a week’s vacation and start something new! As my 40 years with HCD wind down, I’ve started a new career: see me at ronaldjavorbooks.com

Hi Michael! It’s Elaine Clark, now Elaine Williams, in Laguna Beach, CA. I remember the days of Lincoln, IL and your priority of social consciousness. You and your brother were my heroes. It’s fabulous to see you’ve spent your life fulfilling your passions. Thank you for your services and the thousands of lives you’ve not only improved but made a difference in their belief in the system. You remained a persistent, committed and disciplined Advocate for just Doing The Right Thing.

Semper Fi! P.S. Remember the night of hilarious laughter on my part explaining a Paul Newman movie!?!

What a Life of Giving Back; hopefully you are reaping the rewards of a satisfied and fulfilled life, albeit it realized HUD still has a LONG road of changes ahead, mental perspectives being foremost.