Like many tenants who live in Florida, Karla Correa understands the struggle of living in a place that favors landlords over tenants. For the last five years, she’s lived in an apartment in St. Petersburg that has had ongoing issues with leaks and mold, and she’s fought her landlord to get those issues resolved. After learning about a local tenants’ group in another city, Correa was inspired to form her own organization in 2020.

“When I saw that . . . I was like ‘oh we can organize collectively as tenants, just like how we do as workers in labor unions’,” says Correa, who’s 23.

For a year, Correa and other tenant organizers with the newly formed St. Petersburg Tenants Union fought to strengthen local tenant protection laws. They organized community members online and through door-knocking, launched social media campaigns to raise awareness, and built relationships with elected officials on the St. Petersburg City Council. In 2021, their efforts led to several big wins for tenants. For one, the group successfully pushed the city to require that landlords give tenants more notice before a month-to-month lease is terminated. They also secured protections for prospective renters who would use vouchers or other government programs to pay for rent, as these renters are often discriminated against by landlords.

The wins were less than what the group had initially sought, but they were still better than the city’s existing Tenant Bill of Rights, Correa says.

Those protections, however, became moot after Gov. Ron DeSantis signed HB 1417 into law in June. The law gives preemption powers to the state against local ordinances that establish renter protections or regulations that go beyond those granted under state law. Not long after the new law went into effect, the St. Petersburg City Council repealed its own Tenant Bill of Rights.

It’s estimated that more than 45 ordinances in 35 municipalities and counties in the state will be affected, according to Florida House Rep. Tiffany Esposito, a Republican who sponsored the preemption bill.

That includes Orange County’s Tenant Bill of Rights, which passed in January. The bill required that landlords provide a full accounting of all fees to tenants before they move in, and that they give tenants a 60-day notice for rent hikes above 5 percent. The bill of rights also banned landlords from denying a person a place to live based on how they would pay their rent.

Similarly, last year Tampa city officials passed an ordinance that required landlords to inform tenants of their legal rights ahead of their move-in and banned discrimination against renters who would pay rent using housing vouchers or other government-based assistance. Miami-Dade County also passed a Tenant Bill of Rights in 2022, which, among other protections, allowed tenants to deduct repair costs from their rent when landlords didn’t respond to requests within a week.

All these tenant protections, and dozens more, have now been undone.

Organizing for Tenant Protections in a Post-preemption Era

With Florida’s preemption law undoing the work that local housing advocates had secured in recent years, it is difficult to imagine a path forward. But that has not deterred the state’s housing advocates.

“We’re still coming back to the table and we’re proposing solutions from the ground. Preemption is not going to stop us from doing that,” says Santra Denis, executive director of the Miami Workers Center, an organization that played a significant role in securing Miami-Dade County’s Tenant Bill of Rights.

Preemption is a legal doctrine that a higher-level government uses to limit the authority of a lower-level government in enacting regulations on a specific issue. The most common form of preemption is “floor preemption,” when a regulation sets a baseline that lower-level governments must adhere to when setting their own laws. For example, the federal government’s Fair Housing Act sets a minimum standard of housing protections that state and local governments must abide by when passing local laws on housing.

However, the nature of Florida’s preemption law on tenant regulations is what is known as a “ceiling preemption,” which means that the state’s preemption law bars localities from enacting regulations that exceed those set by the state. As such, it is illegal for local governments to pass tenant protections that go beyond what is established by the state, even if localities deem the state’s regulations inadequate in protecting tenants.

For organizers at the Miami Workers Center, a big part of their strategy now is to continue to build support for tenant protections. This includes strengthening its coalition with other advocacy groups, legal partners, and elected officials who are sympathetic to the group’s cause, says Denis. The end goal is to establish tenant protections through other avenues beyond municipal laws, such as diverting local funding toward supportive housing programs. For example, the Miami Workers Center is working with a statewide organization called Florida Rising to establish a right-to-counsel program in Miami-Dade County, which would expand the county’s free counsel pilot program for tenants who are at-risk of or undergoing eviction into a fully funded permanent program. More than 95 percent of tenants who face eviction lack legal representation. Providing renters with a pro bono attorney drastically reduces eviction rates, according to studies.

“South Florida leads the nation in the housing crisis, it’s super pricey,” says Denis, adding that some tenants, for example, have seen their rents rise by a whopping 60 percent in recent years. “People are not able to find a place to live and they’re being evicted.”

Cynthia Laurent, a housing justice campaigner with Florida Rising, says landlords are emboldened to maximize profit because of the state’s lack of housing regulations. “What we experienced even before the pandemic . . . is that landlords were increasing rents at unregulated amounts. And because of this, we even knew folks who are getting rent increases of 30 percent, some folks getting increases of $500 or more per month,” Laurent says. As rents continue to rise with no oversight, thanks in part to the new preemption law, her organization predicts that there will be more evictions and massive displacement of residents.

“[Right to counsel] is something we’re looking to see if there’s a possibility to expand across the state,” says Laurent. She notes that along with work in Miami-Dade County, Florida Rising is also mobilizing tenants for the right-to-counsel campaign in neighboring Broward County.

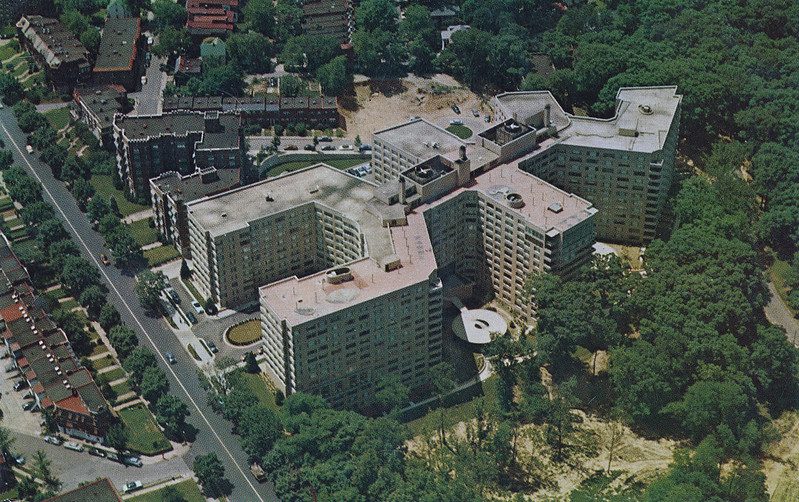

On the heels of St. Petersburg’s Tenant Bill of Rights repeal, housing advocates there have also shifted focus to their next big fight: opposing a $6.5 billion development project approved by the city. The crown jewel of the project is a new 30,000-seat ballpark for the Tampa Bay Rays baseball team—which will be jointly funded, half by the team and half by the city and county—and features a new hotel and other commercial use. The development also calls for 5,700 residential units to be built, including 859 affordable units, and another 600 units of market rate senior housing. Still, local organizers worry that the new ballpark and luxury developments will further raise rent prices in St. Petersburg, where the median rent is already slightly above $2,000.

“We’re trying to mobilize people to come out to the community benefits agreement meetings at city council and then we’re still organizing around the budget,” says Correa of the St. Petersburg Tenants Union. “So even though that [preemption] law passed, it really hasn’t stopped the day-to-day organizing efforts.” In September, tenant organizers in St. Petersburg secured another win: the city council approved $100,000 for its own pilot eviction diversion program, which will provide pro-bono legal counsel for tenants facing eviction.

How to Push for Tenant Protections in Hostile States

Florida is not the only state where tenants’ rights laws are severely lacking. Advocates in other conservative states, like Texas, have also lost tenant protections to state preemption. Texas is considered a landlord-friendly state and, among the 34 cities analyzed across 10 different states by Eviction Lab, Houston and Dallas held the second- and fifth-highest number of eviction filings during the pandemic. Gabriela Garcia, a project coordinator with BASTA in Austin, says Texas advocates are essentially “starting at rock bottom” due to a combination of the state’s weak laws and its lack of organizing culture.

However, they did have some wins. Last year, housing advocates in Austin successfully expanded pandemic-era housing protections through a local ordinance that required landlords to give tenants a week’s notice to fulfill their rent payment before initiating an eviction.

But as in Florida, many of those protections were undone after the state passed what has been nicknamed the “Death Star” bill in June 2023, a sweeping bill that bars cities and localities from passing any law that goes beyond what is already established by Texas law.

“I think that’s probably the [most] frustrating thing, that even if we can get protections locally that they’re so easily squashed by lobbyists later on,” Garcia says. Organizers are now anticipating how legal challenges against Texas’s preemption bill will play out in the state’s courts.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Organizing in Unexpected Places]

It seems difficult to move forward under an all-encompassing preemption law such as the one currently being contested in Texas. However, this is when grassroots organizing becomes a vital strategy. As a nonprofit that works with renters in Austin, BASTA provides legal support and other community assistance to tenants facing housing issues and/or eviction. BASTA works with over a dozen active tenant associations in various housing complexes around Austin and, amid uncertainty stemming from the Death Star bill’s legality, plans to boost education outreach on existing tenant rights in collaboration with legal partners.

Of course, there is the real risk of retaliation when it comes to organizing local tenants against a bad landlord in a hostile state, particularly when working with low-income and undocumented residents. Because of Texas’ weak tenant protection laws, it is easy for landlords to evict tenants who are causing them trouble—say, mobilizing their neighbors to demand long overdue repairs in the building—so it is crucial to strike the right note between transparency and empowerment when working directly with tenants. “Our approach really isn’t encouraging people to be taking the risks, but it’s talking to people about the risks and then being like, hey, this is something that you all want to do, and that we’re being very transparent about what that risk is,” says Shoshana Krieger, BASTA’s project director. “The best course of action is to have an advocate along your side to help navigate it.”

Laws that indirectly support tenants can also aid in shifting the wider culture, such as establishing tenants’ right to organize, as Austin’s City Council did last year. Garcia described an incident in which a landlord had called the police to intimidate tenants who were organizing at an apartment building. The tenants understood that they had the legal right to organize under the city’s law and were able to advocate for themselves when confronted by law enforcement. (Garcia notes that BASTA is operating on the understanding that Austin’s ordinance establishing tenants’ right to organize has not been preempted by Texas’ preemption policy.)

Despite the roadblocks that state preemptions pose, organizers in conservative states are adopting some tactics to advance tenant well-being under hostile conditions:

- Focus on funding for local programs since local governments still have the authority to budget as they see fit. This may include allocating local municipal funds to new programs that empower tenants against mistreatment by landlords.

- Organize to educate tenants about tenant issues and the rights that they still have under state and federal law. Both education and connection with legal resources—particularly in times of uncertainty, such as with the legal battle over Texas’ bill—are imperative to protect tenants.

- Weigh in on development proposals. There is still a lot of organizing work that can be done in the community in the fight against further displacement, like the St. Petersburg Tenant Union’s efforts to mobilize residents against the upcoming stadium development that could worsen housing affordability.

“I think the key is to understand that part of the reason why they passed these laws is to stifle the organizing,” says Correa of the St. Petersburg Tenants Union, citing the emergence of tenants’ groups in Orlando, Miami, and Jacksonville. “If you look at it, a lot of these new laws are in response to the mass tenant organizing that we’ve been seeing all across Florida.”

In Texas, Garcia agrees. “That’s why we need tenants to keep organizing.”

Comments