This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Not Just Ramps—Disability and Housing Justice

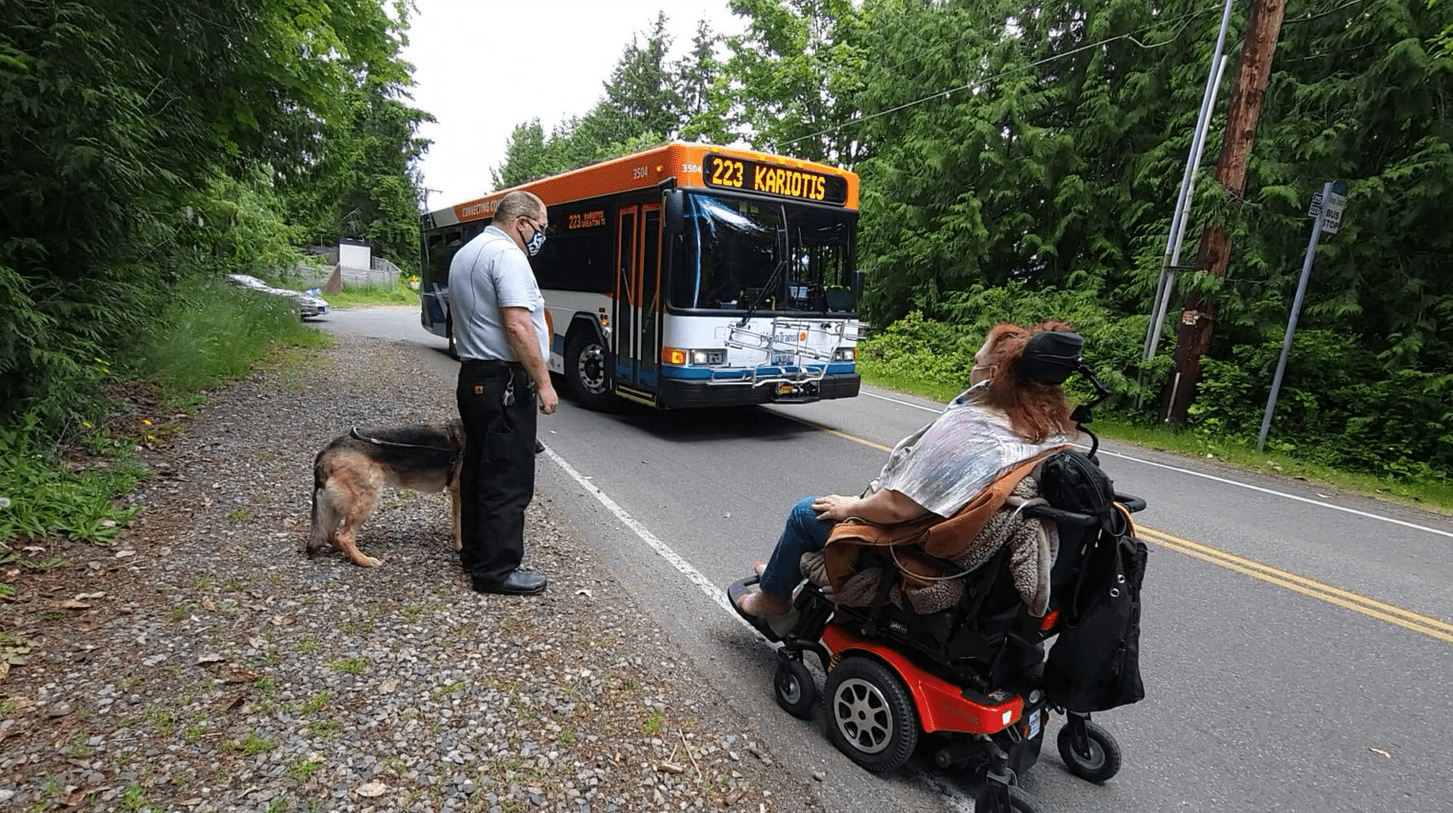

Photo by Flickr user Paul Sableman, CC BY 2.0

Whether you’re a tenant or a homeowner, you’ve probably noticed that staying housed often comes with large one-time costs. A new lease typically comes with a security deposit and sometimes with first and last month’s rent and even a broker fee. Homebuyers need significant savings to cover a downpayment and closing costs, and homeowners frequently need to replace broken appliances, make major home repairs, or retrofit a home to make it more accessible due to a disability.

For many disabled people, however, there’s a big barrier that prevents them from building up the sorts of savings required to handle these expenses (and many other non-housing ones as well): they rely on Supplemental Security Income, or SSI, which has strict asset caps. SSI provides income to low-income recipients who are disabled or are above 65. If you receive SSI, you cannot accumulate more than $2,000 in assets, or $3,000 for couples. Though there is an exception for a home that you own and a vehicle, it’s extremely difficult for recipients to save the funds to acquire those things.

SSI is not the same as Social Security Disability Insurance, which provides payments for those who become disabled after they have been in the workforce and paying into the Social Security system for a qualifying amount of time. SSDI does not have asset caps. SSI, however, is the primary source of income for those disabled people who have never been able to work, or not enough to qualify for SSDI.

Darcy Milburn, director of social security and healthcare policy at The Arc, says she often encounters people who have trouble maintaining housing security because their benefits are contingent on keeping their funds beneath these asset caps.

“As a result of not being able to have a sufficient emergency fund, folks very frequently tell us that they’ve had difficulties with car repairs, home repairs, like getting a boiler fixed, or a roof patch,” says Milburn. And when it comes to building up the funds to purchase a home for themselves, she says it’s been “very much not possible for people on SSI.”

Judy Jackson, a California resident and former teacher who is part of Californians for SSI, wants to see the asset cap increase to $10,000 for individuals and $20,000 for couples. Jackson says that the asset cap that comes with her SSI payments makes it hard for her to manage expenses, including moving to a new residence.

“But there are people that move into apartments where the landlord supplies an appliance, but won’t replace it if it breaks down. So they have to on their own figure out a way to buy a refrigerator or a stove if they break,” says Jackson. “If I knew I could save up money ahead of time for moving, then I would.”

One of the reasons these asset limits are so strict is that they’re outdated. The SSI program was created in 1972, and the limits haven’t been updated since 1989. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, the limit would now be nearly $10,000 if it had been updated for inflation.

Not only are asset limits a heavy financial burden, they’re difficult to navigate. Joanna Ain, associate director of policy at Prosperity Now, says these caps are confusing, “especially because they change depending on what program. Are we talking about TANF [Temporary Assistance for Needy Families]? Are we talking about SNAP [Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program]? Are we talking about LIHEAP [Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program]? Depending on what program we’re talking about, the asset limits are very different,” says Ain. Federal asset limits on SNAP, for example, are capped at $4,250 for households in which a family member has a disability, and state limits vary.

The way assets are counted fluctuates based on the benefit type, too. For example, a California resident with a disability would be subject to a $15,317 asset limit for TANF, and could save in a retirement account without affecting this limit. But the same individual is subject to a $2,000 asset limit—retirement account included—to access SSI benefits, and is subject to no limit at all to qualify for LIHEAP or SNAP. In California, TANF applicants can keep a vehicle worth up to $25,483 without affecting their asset cap—but in Connecticut, the same TANF applicant could only exclude a vehicle worth $4,500.

Tracey Gronniger, managing director of economic security at Justice in Aging, a nonprofit that addresses poverty among older adults, says that SSI asset limits can be confusing. “I think that SSI is one of the more complicated programs that exists in terms of figuring out how you qualify, how you maintain your eligibility, why you may or may not be seeing your benefit reduced or terminated,” Gronniger says.

An Option to Save

Recognizing that the inability to save puts disabled people in a precarious financial position, in 2014, Congress created ABLE Accounts (short for “Achieving a Better Life Experience”), which enable SSI recipients to save beyond SSI asset limits. ABLE accounts are exempt from SSI asset caps (up to $100,000), and they allow disabled people to save up to $16,000 each year without paying taxes on the funds. They also don’t count against individuals when they apply to other benefits programs. Funds in ABLE accounts can only be used for “qualified disability-related expenses,” which include housing, medical needs, and schooling. Otherwise, the owner of the account is charged taxes and penalties on the funds, and could even jeopardize their benefits.

There’s historically been one big problem with ABLE account eligibility: only people who were disabled by their 26th birthday could access them. That restriction was recently relaxed to age 46, although the change won’t take effect until 2026. But even with the updates, individuals who became disabled after the age of 46 and are in need of SSI to support themselves are blocked from this route to save up funds for crucial expenses.

In addition, some people who qualify may not be accessing the service, Milburn says, because they’re simply not aware of the option.

Individual Development Accounts, or IDAs, are likewise exempt from SSI asset caps. These accounts can be used to save up for qualified expenses, including purchasing a home. Funds deposited by the user are supplemented, often by TANF. However, recipients must receive income from a job to qualify.

Housing Choice Vouchers

One option for SSI recipients to help them afford housing is the Housing Choice Voucher Program. With the program as it stands, Section 8 doesn’t adequately address need–just a fifth of eligible households receive vouchers. However, people with disabilities do make up a significant portion of people receiving vouchers: 25 percent of all Housing Choice Voucher holders are disabled, and a still-higher proportion of heads of households have disabilities.

Though it is not well known or widely implemented, vouchers can be used for homeownership, not just renting, though not every housing authority participates in the program. Under the voucher homeownership program, voucher payments can be used toward homeownership expenses rather than rent. However, no downpayment is provided, so SSI recipients without an ABLE account or some other downpayment assistance program may still have trouble accessing homeownership this way.

Even less well known is that there are many exceptions to the eligibility requirements for the Section 8 homeownership program for disabled participants. They don’t need to be first-time homeowners or employed, their income threshold to qualify is set to the amount provided by SSI, and their assistance isn’t limited to 10 to 15 years. The program also provides for other reasonable accommodations for disabled residents upon request.

On the Ballot

There’s legislation in progress that could raise asset caps, offering those who use SSI and other government benefits the chance to build savings and economic security.

Both the SSI Restoration Act, reintroduced in 2021, and the 2022 Savings Penalty Elimination Act would raise the total asset limit for recipients of SSI to $10,000 for a one-person household and $20,000 for a two-person household. The proposed laws would also require that these limits be annually increased to keep pace with inflation.

Notably, both acts would ensure that the asset cap for married couples increase by twofold over the cap for individuals, unlike the current system. The $3,000 asset cap—which affects recipients regardless of whether their spouses can also receive SSI benefits—is just one of many rules that make it difficult for disabled people receiving benefits to marry without affecting their finances.

“It is unacceptable that under our current system, married couples are only allowed, the SSI recipients are only allowed, to have $3,000 in assets. And this is an incredible barrier to people being able to marry who they love,” says Milburn. “People just should not be forced to choose between continuing to receive the benefits that they are eligible for and deserve and need, and being able to build a future with their partner.” Married couples who receive joint SSI benefits are additionally penalized through a reduced monthly income: together, they receive just 150 percent the amount that individuals do. The Arc supports legislation that would improve economic security and marriage equality for people with disabilities, including the Marriage Equality for Disabled Adults Act.

As advocates await change, caps continue to keep a population that numbers nearly 7.5 million from accessing a basic right: financial security. According to the Urban Institute, the majority of these recipients “remain within 150 percent of the federal poverty level.”

“When I think about the financial advice that I received from my parents, it was related to having an emergency fund, starting to save for retirement, setting up automatic transfers for savings, and doing things like buying in bulk, and then also saving for a home,” says Milburn. “These are all things that people on SSI are not allowed to do effectively because of the SSI asset caps.”

Comments