This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Not Just Ramps—Disability and Housing Justice

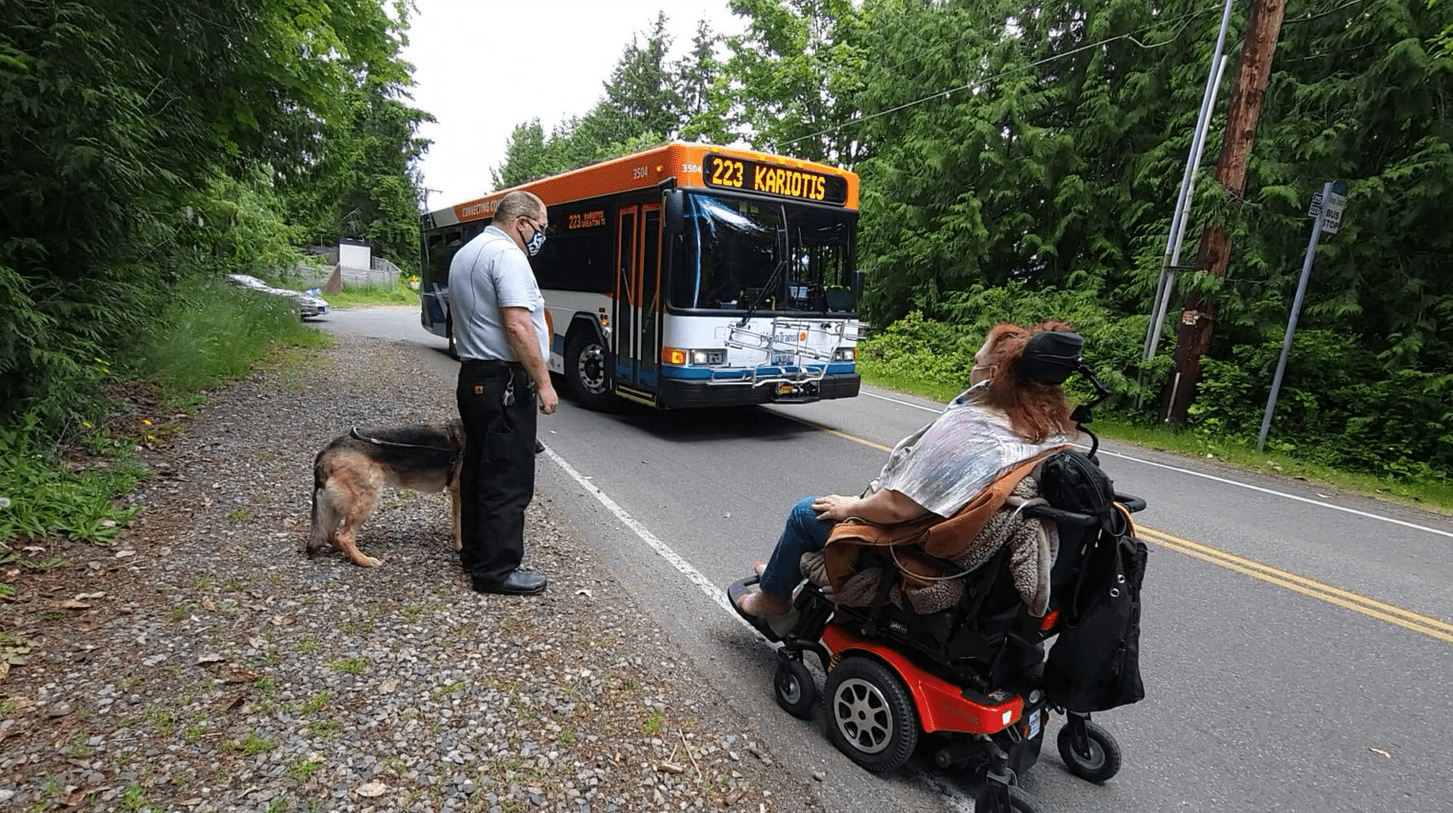

Photo by Flickr user Tamás Zádor

As the homelessness crisis continues to grow across the United States, the accessibility of emergency shelters has become ever more critical in guiding vulnerable individuals toward appropriate care.

Individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities or mental illnesses are disproportionately more likely to experience homelessness. Homelessness additionally contributes to premature aging, and research shows that eviction can negatively impact birth outcomes and the health of young children, says Giselle Routhier, a research assistant professor and co-director of the Health x Housing Lab in the Department of Population Health at New York University.

But the layout of the country’s shelter system, a critical social safety net to help those experiencing homelessness, often leaves much to be desired. Most shelters lack appropriate space or accommodations for people with disabilities—if they have them at all.

Accessible Spaces

In 2017, New York City’s Department of Homeless Services agreed to do more to accommodate unhoused individuals with disabilities as part of a settlement.

A class action lawsuit, Butler v. City of New York, was a push by disability advocates to force the city to better treat their needs and to, within five years, be able to accommodate any disabled person. The department found that about two-thirds of the single adults using New York City shelters were in need of these accommodations.

“If a person has multiple disabilities, it’s going to be really challenging for them to have full access in the shelter program,” says Sharon McLennon-Wier, the executive director of the Center for Independence of the Disabled, NY, one of the groups that filed the class action lawsuit.

There’s a long list of reasons why shelters may not be accommodating, but foremost is the layout and structure of the buildings—not just in New York City, but throughout the country.

In York County, Pennsylvania, which has a population of about 460,000 people living in a combination of rural, suburban, and urban areas, one of the biggest challenges facing the shelter system is the “composition of the physical space” available, says Kelly Blechertas, the program coordinator for the York County Coalition on Homelessness. Shelter buildings are often inaccessible to people with disabilities.

“They are old buildings, they often have lots of stairs and are pretty big, so there’s a lot of traversing back and forth across the building [and] we only have one emergency shelter room in York County that is handicap accessible. And it’s a family shelter,” Blechertas says. “So, if you are, for example, a single man in need of that accessibility, it’s not available to you.”

Likewise, some of the older buildings in New York City, McLennon-Wier says, “are not equipped with ADA showers, or grab bars. There’s steps, some have elevators, some do not.” Many buildings do not have electric outlets readily accessible for people who need to be on oxygen or have other medical devices that need to be plugged in. McLennon-Wier says that little has changed in the state of shelter accessibility in the city since the settlement.

If a person makes it into the shelter system, they are usually placed in a building with little to no accommodations not just for physical disabilities, but also for what McLennon-Wier calls “hidden disabilities.”

“The hidden disabilities, the ones that you don’t have an obvious identifier—the crutch, the cane, or a wheelchair—are challenging,” she says. “Someone that has a developmental disability: they’re on the spectrum, they have Tourette’s, or they have a tic disorder, and because of it they may have vocalizations that may just come out of the blue. If you’re in a shelter, where there’s a lot of people sleeping in the same space, and all of a sudden you have [an] obvious vocalization, people may think, ‘Oh, there’s something wrong,’” she says. “I think it’s very important to know that there are different types of behavioral, developmental, mental health disorders that will show up in people who are unhoused in addition to having a physical disability as well.” McLennon-Wier says that using universal design—making sure shelters that are newly built or renovated are designed based on a standard that accommodates people with both physical and mental disabilities—could be a solution.

Once they’re in a shelter, disabled individuals often find the area difficult to cope with. Some people with disabilities sometimes “just don’t do well in those types of situations where there’s tons of people, tons of noise, altercations,” says Tina Murray, the senior director of crisis engagement programs at Together, an Omaha-based organization which operates a non-congregate shelter.

Most shelters function as congregate shelters, with varying restrictions on who can access them. Congregate shelters often utilize bunk beds to maximize space, which often leave individuals with disabilities unable to climb in and out of what could be their only bed for the night. Limited hours of operation can also be restrictive.

“It’s hard to be told that you have to be in your bunk at 9 and get up at 6 and then pack up your bunk and then take your stuff with you all day,” says Murray.

Many shelters additionally have restrictions on allowed types of households, whether individuals, families, or couples.

“We just had this happen recently . . . There was a man who was in a wheelchair, and his caregiver was the female he had with them and they had to be separated, so we put them in a hotel because there’s no shelter that will take them as a couple,” Murray says.

Some domestic violence shelters may not be accessible for children either, says Jewelles Smith, a consultant in disability human rights.

“Too often, government, people, judges, and such think an abusive man who’s able-bodied is a better parent than a disabled woman because of ableism. Like, it’s just ableism, full stop,” she says. “When we don’t have accessible shelters for women to flee to with their children, then we compound that. So, you either stay in an abusive situation where you could die, to be with your children, or you lose your children.”

Nowhere to Go

New York City, which in March saw more than 75,000 people using its shelter system each night, remains the only city in the country where a complete legal right to shelter ensures that the city’s shelter system expands appropriately to meet the needs of those unhoused individuals.

But that legal right is now under threat. In May, New York City Mayor Eric Adams requested to suspend the city’s decades-old right-to-shelter law.

Adams claimed that the influx of migrants into the city has strained the city’s resources to handle its unhoused population—despite reports that “more than 1,000 beds and several hundred family units” were unused, according to Gothamist.

“It is in the best interest of everyone, including those seeking to come to the United States, to be upfront that New York City cannot single-handedly provide care to everyone crossing our border,” he said in a statement.

And while New York City could revoke its right to shelter, most states and cities do not have these protections in the first place.

“Overall, in places that don’t have a legal right to shelter, one of the bigger barriers is literally just not enough space,” Routhier says. “There may be long waiting lists. There may not be places for someone to go.”

Youth Emergency Services, an organization that runs a youth-specific shelter in Omaha, Nebraska, often doesn’t have enough beds for the youth who are experiencing homelessness, says executive director Kalisha Reed.

“There’s only the one shelter from my understanding in the Omaha metro area that is youth-focused … [and] we only have five beds.” Reed adds that the beds are full “every single day.”

Capacity issues often affect domestic violence survivors as well.

Blechertas says that York County’s domestic violence shelter recently renovated to make its space less congregate, but still faces strained capacity. Instead, some individuals experiencing domestic violence must stay at other, traditional shelters. “There isn’t necessarily the volume of domestic violence related services available to them in a traditional homeless shelter, but that’s where we’re able to keep them safe,” Blechertas says.

But one of the largest barriers to accessing shelters is whether they even exist at all. Shelters tend to be concentrated in urban centers, and rural areas often lack any shelters nearby.

“Rural homelessness often presents a little bit differently from urban homelessness,” says Anne Sosin, a policy fellow at Dartmouth’s Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for Public Policy and the Social Sciences. Sosin is also the interim director of the Vermont Affordable Housing Coalition. “Often if you’re in an urban area, you will see encampments, people staying on the street. In rural areas, it’s often much more hidden. The face of rural homelessness is often couch-surfing, sleeping in cars—it’s not staying in a shelter.”

If there is a shelter available, it may be miles away, and there may be no place to park a car without getting ticketed or finding it broken into.

“Shelters may be very far away or hard to access, there’s no capacity, shelters are not often desirable—many shelters are congregate, they briefly force guests out in the morning, so they don’t have a safe and stable place to stay,” Sosin says. “If you’re worried about having your belongings taken, about violence, about other things, you may opt to sleep in another place than a shelter. It’s a common experience across the U.S.”

In Vermont, which has the second-highest per-capita rate of homelessness in the U.S., behind only California, there is an “extreme shortage of shelter,” Sosin says.

“It’s one of the reasons why we’re so reliant on motel-based shelter,” she says. “The conventional shelter capacity is simply not sufficient to meet the needs of people who are experiencing homelessness.”

The Northeast Kingdom—the northernmost area of the state—is “ground zero” for Vermont’s homeless crisis. Sosin says the region has no shelters whatsoever. For years, it relied exclusively on a motel voucher program that was kept running via federal COVID relief funds. That program is now ending.

A lack of both state and federal funding, as well as stringent local zoning regulations, often prevent the development of shelters.

“It’s very hard to build any type of homeless housing structure, there’s a lot of NIMBYism,” Blechertas says. “People are afraid of what it will bring to their community, even though you could argue the people staying there are people from the community anyway.”

A Long Way to Go

Six years after the Butler case settlement, McLennon-Wier says the city is still working with her group to implement obligations as laid out in the settlement.

The city’s Department of Homeless Services, she says, has adopted language and policies to identify and accommodate disabled individuals, there’s been more training for staff and case workers on the front lines to help identify and accommodate disabilities that might get overlooked, and some infrastructure has been modernized.

“If there wasn’t this case, I don’t think that level of infrastructure and policy change would have happened,” McLennon-Wier says. Her group is still working with the city to implement a universal design—where all buildings, both new and renovated shelters, have the necessary accommodations for physical and mental disabilities, “because it takes more time and money to retrofit all old spaces,” she says. “If you’re putting up new shelter programs, new buildings, you have to go in there with a 2050 kind of viewpoint: What is the population going to look like for the next 27 years, and how are people changing, and build that infrastructure into these new shelters so that they’re accommodating to everybody.”

But the shelter system in New York City—and throughout the country—still has a long way to go.

“It takes advocates to keep pushing forward to hold people accountable, because a lot of these shelters are inhumane—we’re talking about really decrepit places no one would want to live, regardless of if you are unhoused,” McLennon-Wier says.

|

Help keep us strong by becoming a Shelterforce supporter. |

Comments