This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Not Just Ramps—Disability and Housing Justice

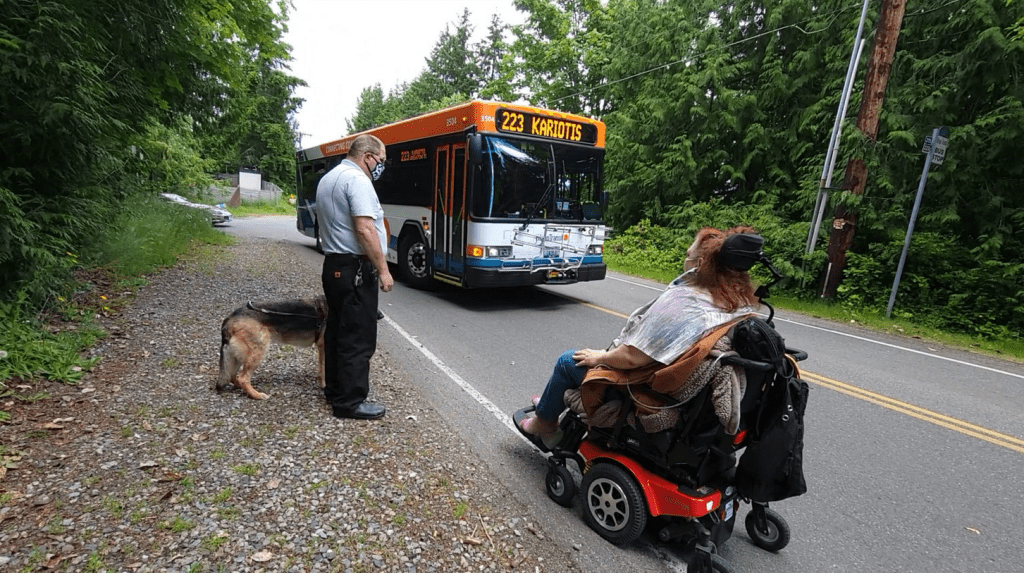

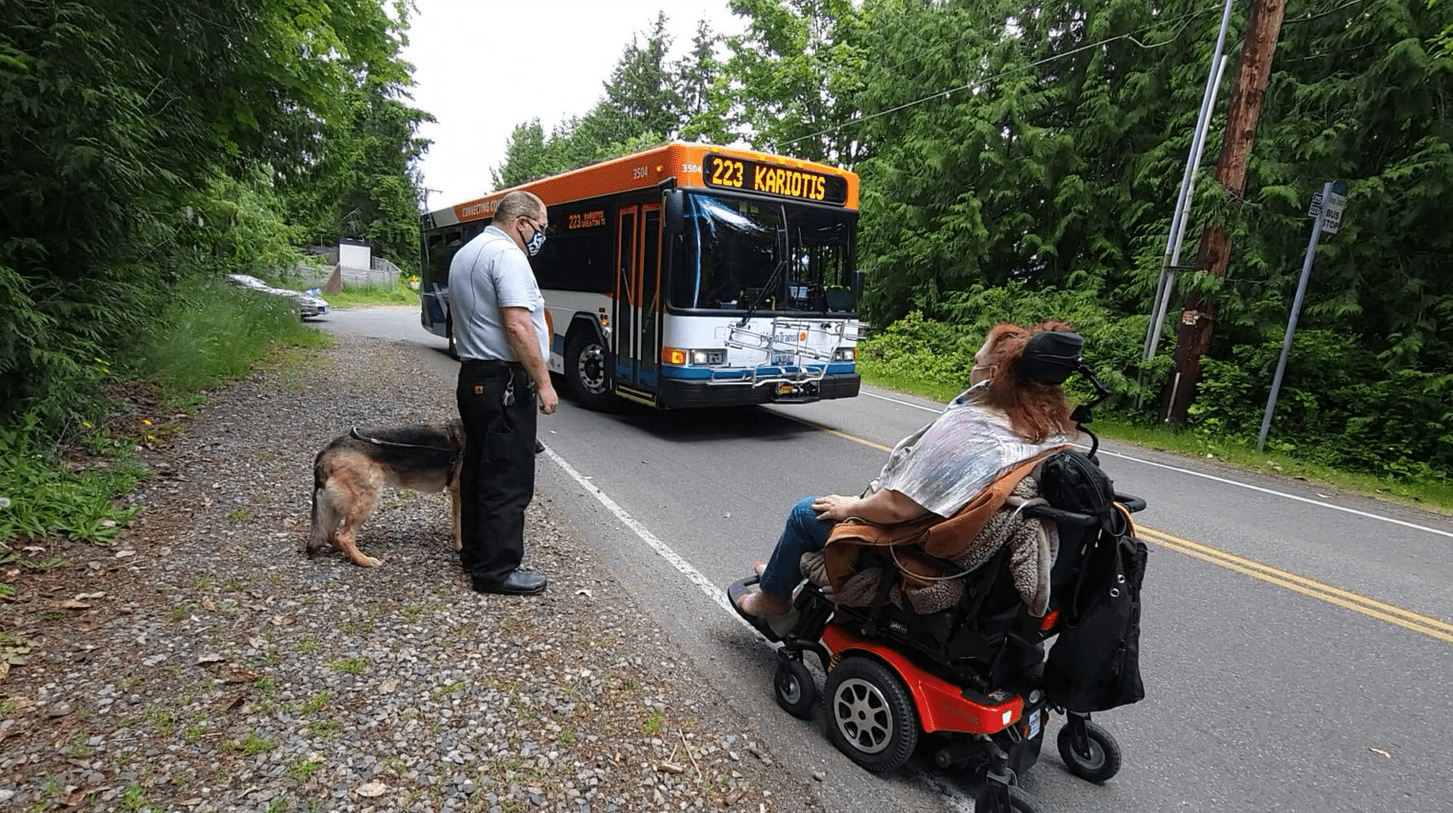

In a podcast titled “The Road is the Sidewalk,” disabled residents of Kitsap County, Washington, describe how lack of access impacts their lives. Photo courtesy of the Disability Mobility Initiative

Three things top the wish lists of many housing and community advocates: a diversity of housing options near jobs, schools, and shopping; sidewalks that are safe and accessible; and transit service.

The common thread that connects these goals is transportation equity: striving for fairness in mobility and accessibility to meet the needs of all community members, particularly people with disabilities, a traditionally underserved population.

Accessible, affordable, and reliable transportation options are vital to connect people— particularly those who do not drive—with social and economic opportunities, preferably near where they live. But making that accessibility and opportunity a reality is difficult: it requires prioritizing the coordination of investments in both housing and transportation, a complex task. Pursuing transportation equity to create more connected communities requires careful management of several elements:

- Accessible transportation modes, especially for pedestrians, bicycle riders, and transit users.

- Meaningful community input, particularly from people of color, LGBTQ+ community members, persons with disabilities, residents of rural areas, and low-income households.

- Proximity of destinations, such as affordable housing, employment hubs, grocery stores, and parks, and routes that efficiently connect them to one another.

- Interagency coordination among those with responsibilities that affect housing and those that affect transportation, such as transit agencies, and engineering, public works, and planning departments.

- Financial resources and technical assistance, such as the support provided by the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for technical assistance to assist local stakeholders with planning for integrated housing and transportation.

It requires time to realize change in some of these elements. Making destinations closer to each other, starting from a landscape shaped by decades of car-based sprawl, will require zoning reform, infill development, and political will. Even then, change will not be immediate—but it is part of transportation equity. “People want to live near transit or sidewalks, but there’s not enough housing. We need to look more carefully at how to create affordable housing near sidewalks and transit,” says Anna Zivarts, director of the Disability Mobility Initiative Program with Disability Rights Washington.

Funding is also uncertain, with warnings of a transit fiscal cliff being sounded amid declines in transit ridership and workforce shortages.

Despite these challenges, local transportation equity advocates can lay the groundwork for future transportation improvements by revealing the gaps in safe and accessible modes of transportation, documenting where those problems lie, and prioritizing meaningful participation in all transportation planning and decisions from people with lived experience.

Transportation Equity for People with Disabilities

People with disabilities regularly encounter limited transportation access. Disabled people age 18 to 64 take fewer trips for work, social, and recreational outings than people without disabilities. An estimated 3.6 million people are kept from leaving their homes by their disabilities. And nearly half of them, 1.7 million people, are adults younger than 65.

One of the biggest challenges to achieving transportation equity for disabled people is “overcoming bad attitudes” on the part of people who are in a position to make improvements, according to Michael Shermis. special projects coordinator for the city of Bloomington, Indiana, where he serves as ADA coordinator and human rights director.

For example, sometimes restaurant owners or retail stores may decline to remove barriers to their place of business, despite the availability of solutions that would increase access for potential customers and cost little or no money to implement. In other cases, the challenge may be a municipal budget that does not prioritize accessibility. Allocations for sidewalks are often limited, yet many sidewalks need repair or replacement—when they exist at all. But those who primarily drive resist diverting funds away from car infrastructure.

The good news is that people who have more information about mobility challenges are more receptive to changes, according to Shermis. And opportunities to educate the public about the change that is needed to advance transportation equity are growing, as disabled journalists and advocates increasingly share their experiences with transportation accessibility challenges. For example, The Road Is the Sidewalk is a five-episode podcast produced by Disability Rights Washington in collaboration with Zack Hurtz, a blind podcaster from Kitsap County. The series features disabled residents of Kitsap County describing how lack of access impacts their lives, as well as interviews with researchers working to improve sidewalk accessibility.

TikTok, likewise, has offered many creators a valuable means to highlight accessibility issues, such as getting left behind by city buses, unreliable paratransit, obstacles posed by scooters or vegetation, dangerous crossings, seasonal hazards, or everyday sidewalk fails. Some efforts are broad-based: Transportation Access for Everyone Storymap, produced by the Disability Mobility Initiative, shares stories of the transportation equity challenges of nondrivers from every legislative district in Washington state.

In Washington state, the Disability Mobility Initiative Program spearheads initiatives such as the “Week Without Driving Challenge.” Now in its third year, the challenge asks elected leaders to put themselves in the shoes of nondrivers by spending a week getting to their daily destinations without driving themselves.

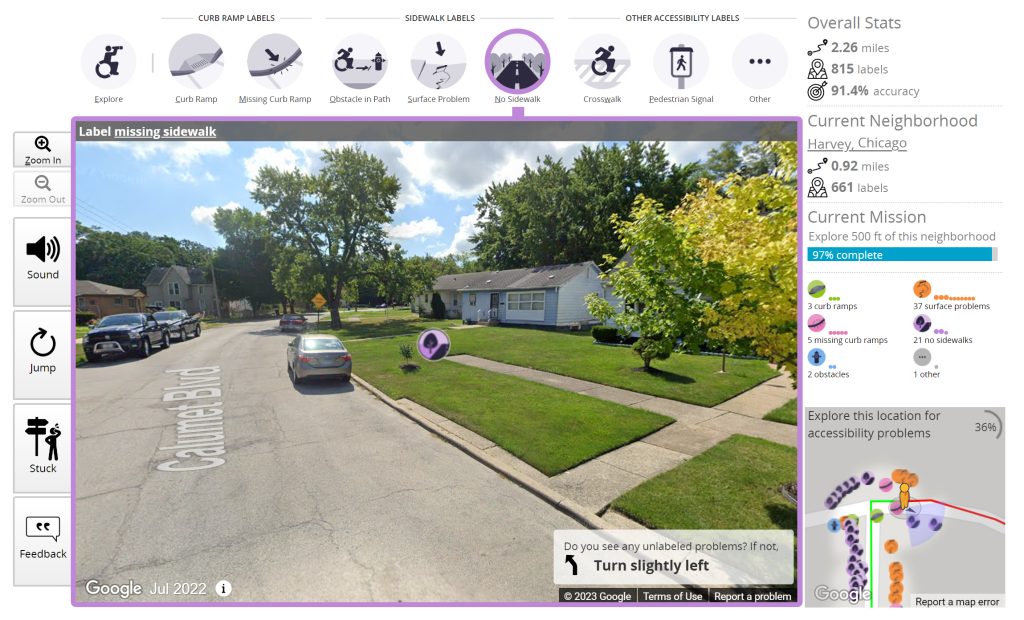

Project Sidewalk, designed and operated by the Makeability Lab at the University of Washington, is one of the most comprehensive efforts to track and highlight the condition of pedestrian infrastructure. It seeks to map and assess sidewalks worldwide using remote crowdsourcing, artificial intelligence, and online map imagery. Project Sidewalk is currently deployed in 14 cities across six countries, including Seattle, Amsterdam, Mexico City, and Taipei. The project has collected over 1 million data points—possibly the largest open dataset of sidewalk accessibility assessments ever collected.

Project Sidewalk volunteers remotely explore city streets using Google Maps to find and label accessibility issues, such as a missing sidewalk. Photo courtesy of Project Sidewalk

Led by Jon Froehlich, an associate professor in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of Washington, and David W. Jacobs, a professor in the Department of Computer Science and UMIACS at the University of Maryland, Project Sidewalk volunteers remotely explore city streets using Google Maps to find and label accessibility issues. The Project Sidewalk research team uses these labels to inform city planning, build accessibility-aware mapping tools, and train machine learning algorithms to automatically find accessibility issues.

“Project Sidewalk is part of an ecosystem of tools,” Froehlich explains. “It is one of the fastest, most lightweight ways to get started.” However, even with data that is gathered remotely, Froelich notes, local participation is still required for Project Sidewalk to have an impact. Key Project Sidewalk questions to ask local partners are: What is your need? What do you plan to do with the data? How will you sustain that commitment?

Leading the effort to document sidewalk accessibility in the Chicago region is Project Sidewalk collaborator Yochai Eisenberg, assistant professor in the Department of Disability and Human Development at the University of Illinois-Chicago. Eisenberg notes that a focus of his research is examining what communities are doing to remove accessibility barriers, adding, “Sharing the data is key: that’s the part that empowers advocates.”

Eisenberg’s team has partnered with agencies and community organizations in the Chicago region that oversee sidewalk accessibility planning and implementation—including the Regional Transportation Authority, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, the Metropolitan Planning Council, and the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus.

ADA Opportunities and Challenges

What about the Americans with Disabilities Act? Doesn’t that deliver transportation equity?

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) is the landmark civil rights law that addresses the rights of people with disabilities. Title II of the ADA prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in public transportation services, such as city buses and public rail, and the ADA has enabled major improvements in accessibility in public transit systems around the country. It requires that all new fixed-route, public transit buses be accessible and that transit providers offer supplementary paratransit services for individuals with disabilities who cannot use fixed-route bus service.

And yet, 32 years after passage of the ADA, transportation equity still has significant gaps. Compliance is inconsistently monitored or enforced. Many streets, sidewalks, and businesses remain inaccessible around the country. Although paratransit is more expensive to operate than regular public transport, there is no direct federal funding for it, making it an unfunded mandate. Transportation options are more limited in rural areas, and in places with no public transportation to begin with, paratransit is not required by the ADA.

“Fixing things that aren’t ADA accessible often falls on the individual facing the obstacle. … It’s not a systems change,” notes Carrie Diamond, co-director of the National Aging and Disability Transportation Center and senior director of transportation and mobility at Easterseals Inc.

After the 1990 federal law was passed, state and local governments and other public entities were each required to create an ADA Transition Plan to ensure that they complied with the law and individuals with disabilities are not excluded from programs, services, or activities. These transition plans should identify barriers to accessibility for people with disabilities and develop a schedule for making modifications. The responsible agency is supposed to update the plan periodically until all accessibility barriers in the public right of way are removed. Unfortunately, the implementation of ADA Transition Plans is often uneven—and 33 years later, many communities still have not even created their plans.

Weekly trash and recycling bins can create significant barriers for accessibility. Photo by Deborah L. Myerson

“In theory, they have to show that they have an ADA Transition Plan to be eligible for federal transportation funds,” Zivarts explains, “but many communities still haven’t done that” and their funds have not been withheld. Washington state is currently surveying which communities have ADA Transition Plans and which do not.

“The ADA is great in many ways, but it clearly didn’t go far enough. There are no penalties for people who don’t comply,” observes Shermis. “Look around at all the places that are still not accessible.”

Nothing About Us Without Us

“Nothing about us without us” has long been a mantra for the disability rights movement. Agencies and organizations in various parts of the country are developing practices rooted in inclusion to realize better outcomes for transportation equity.

Transit Planning 4 All works to increase inclusion in transportation planning and services for people with disabilities and older adults. The program is sponsored by the Administration for Community Living in collaboration with the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Transit Administration.

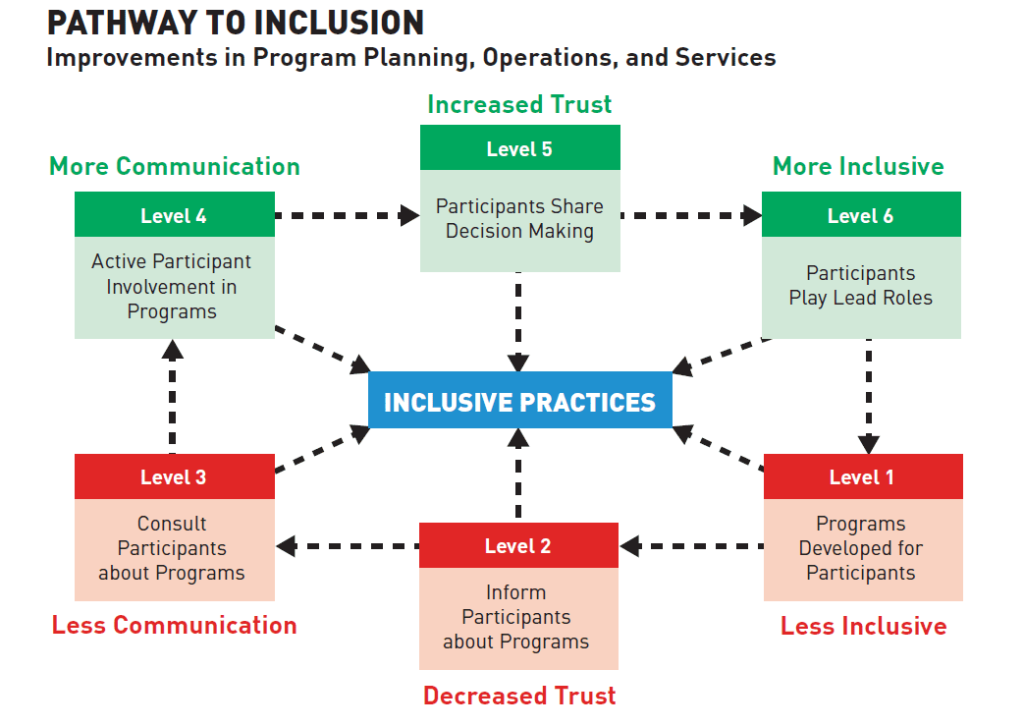

The Pathway to Inclusion is a graphic tool that organizations can use to distinguish between the types of active and meaningful inclusive activities in their programs and their communities. Image courtesy of Transit Planning 4 All

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) received a grant in 2020 from the Transit Planning 4 All program to inclusively plan and implement Ride On, a mobility on-demand solution with and for older adults and people with disabilities. As part of this effort, SDOT made inclusive engagement a throughline, rather than a phase: community participants were involved at every stage of the project. SDOT convened a compensated steering committee of end users to plan, implement, and evaluate the Ride On program. With a focus on responsiveness, trust, and existing relationships, the initiative included shared power and decision making with community stakeholders.

New opportunities for transportation equity are available under the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which established the new Safe Streets and Roads for All (SS4A) discretionary program to fund regional, local, and tribal initiatives through grants to prevent roadway deaths and serious injuries. With $5 billion in appropriated funds over the next 5 years, eligible grant activities include equity considerations developed through a plan using inclusive and representative processes.

For example, the city of Tampa, Florida, received a 2022 SS4A award of $20 million for T-SAFE: Tampa—Systemic Applications for Equity. The project is constructing new sidewalks and separated bicycle lanes with a focus on improvements near schools, parks, and transit routes. In addition, the project is developing a Pedestrian Safety and Equity Action Plan.

In the city of Bloomington, Indiana, the Council for Community Accessibility (CCA) adopted Accessible Transportation and Mobility Principles to advance a genuinely inclusive approach to citywide improvements and development of public spaces. The principles were produced by a CCA committee with technical assistance from Health by Design.

The first of the set of principles is their foundation: “Involve people with disabilities in decision-making.” The aim is to establish a transparent, equitable public process that includes people with low vision, mobility challenges, and other disabilities in a full range of transportation decisions from design to operations.

Shermis sees Bloomington’s proposed Accessible Transportation and Mobility Principles as “an opportunity to include people with disabilities in conversations at a level that makes a difference.”

“It’s one thing to say, ‘open to everybody,’” Diamond says. “But why are certain people not involved? Is there a way for people to request language or translation assistance? Is it accessible to get inside? Every step of the journey needs to be accessible.”

Editor’s Note: An earlier version of this article misstated a statistic about housebound disabled people.

|

Help keep us strong by becoming a Shelterforce supporter. |

Comments