New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy tours storm damage in New Jersey after Hurricane Ida in 2021. The remnants of the storm killed more people in New Jersey than in any other state. Photo by Edwin J. Torres of the NJ Governor’s Office, via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

New Jersey’s Holmdel Township settled a seven-year battle over its Fair Housing obligations, and subsequently planned 300 low-income housing units to be placed on wetlands and flood-prone lots. This occurred not in the 1950s but during the pandemic, and less than a decade after Superstorm Sandy brought flooding and devastation statewide. Initially the units were to be sited at Bell Works, a sprawling former corporate campus, seen on Apple TV’s “Severance,” that is now a massive redevelopment project. Instead, the units were moved off campus with the approval of the township council. In January, Holmdel filed with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) for a waiver to redevelop a wetland lot, the new location for some of the low-income housing units.

Transferring the “affordable” income developments to precarious circumstances should have raised red flags. In a state where storms like Sandy are a recurring threat—the remnants of Hurricane Ida last year killed more people in New Jersey than in any other state—it is unlikely Holmdel officials do not understand the risks from floods and storms.

Holmdel’s recent actions perpetuates something called “climate gentrification.” Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg, Ph.D., of University of Massachusetts Global, describes climate gentrification as valuing certain properties over others specifically based on a property’s ability to accommodate settlement and infrastructure in the face of climate change. This deepens racial and socioeconomic divides, as areas of land that cannot withstand these changes are left to the less affluent. Recent death and devastation on Staten Island from storms like Ida and Sandy, and the location of certain housing stock, can be linked to climate gentrification.

How It Began

Holmdel Township is a wealthy suburb of New York City. Its median household income is $149,432. Roughly 77 percent of Holmdel’s 17,000 residents are white, and nearly 90 percent of Holmdel’s housing stock is owner-occupied homes, which have a median value of $661,800.

Plans for low- and moderate-income housing came about through compliance with a 2019 Fair Housing settlement (as the township’s affordable housing obligations have spanned decades of legal challenges). Today, Holmdel’s ordinances have evolved to harness affordable-housing “linkage”: developers are required to help finance affordable housing construction as a condition for receiving permission to build, or to obtain a density bonus for their construction projects. As the pandemic unfolded and Holmdel’s Planning and Township committees began meeting online, the two committees approved a Payment in Lieu (PIL) structure for the Alcatel-Lucent Redevelopment plan that encompasses the Bell Works campus, meaning that developers could opt to pay a fee in lieu of constructing affordable units on-site. This essentially allows developers to avoid putting mixed-income units together on the same property. Generally, PILs or “lieu-fees” are paid to a housing trust fund. Called a loophole by inclusionary housing advocates, the PIL that Holmdel officials approved legally transferred housing intended for the economically vulnerable away from the Bell Works campus.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Blame Policies, Not Places, for Poor Health]

Prior to the PIL transfer, Holmdel had decided to rezone a wetland lot that borders a different town, to an affordable housing multi-family zone, designated AH-MF.

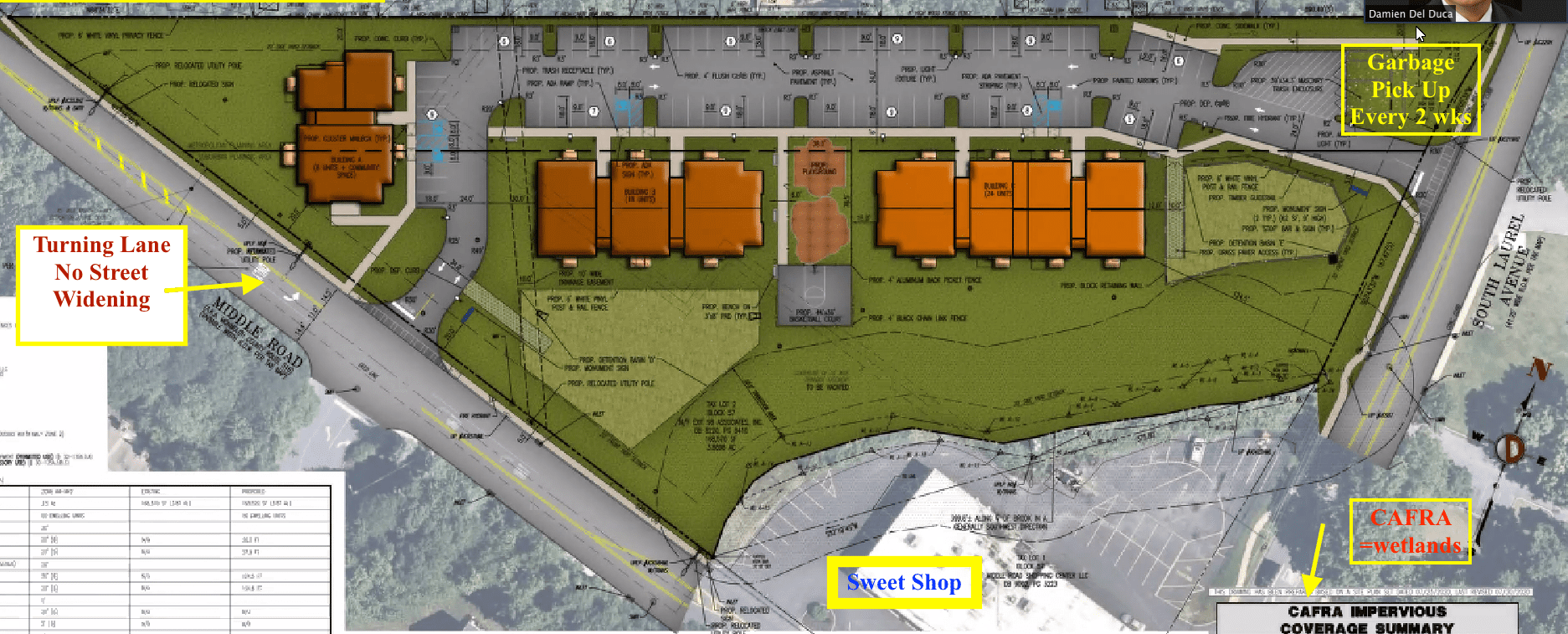

One portion of the transferred units are to be constructed on Palmer Avenue, Block 52, an undeveloped flood-prone lot on Holmdel’s border with Middletown Township. Another portion is to be built on 625 South Laurel Ave., Block 57, a wetland lot situated on the border between Holmdel and Hazlet Township. For the latter property, Holmdel quietly applied this year for a waiver from NJDEP to begin development on the wetland property. A public comment period about the wetlands development waiver opened on April 20, 2022, and will remain so for 30 days.

Issues With the Locations

A site plan for the proposed affordable housing development, which is located on a flood-prone lot. Rendering courtesy of Holmdel Township

The undeveloped Palmer Avenue lot was a known flooding hotspot, according to the local press. The mayor of Middletown, the town that shares Holmdel’s border with the property, took the rare action of appearing at Holmdel’s Planning Board last March, stressing the drainage issues.

The South Laurel Avenue lot is a wetland that has a branch of the Waackaack Creek running through the property. In its January filing, Holmdel attempted to change the property’s CAFRA wetland designation so that the developer can build low-income housing there. CAFRA stands for the Coastal Area Facility Review Act, which created categories of land use in New Jersey for activities posing the most risk to the coastal environment. CAFRA designations and land use permits are managed through the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.

Additionally, prior to its rezoning as an AH-MF lot, the South Laurel Avenue lot once housed a nursery business, which in addition to plants and seeds sold commercial-grade pesticides and fertilizers to farms in the area. Furthermore, the AH-MF lot is adjacent to a strip mall that housed a dry-cleaning business for decades. Yet no plans for soil or water testing were ever announced or, if tests were conducted, made public.

According to the American Planning Association’s 2019 Planning for Equity Policy Guide, zoning has historically been used “to exclude multifamily rental housing from neighborhoods with better access to jobs, transit and amenities.”

Had the low- and moderate-income housing remained part of the Bell Works campus, access to jobs and transportation were all but guaranteed for its future residents, and flooding would not have been an issue. The redevelopment of the Bell Labs campus is promoted as a “one-of-a-kind destination for business and culture” and has been widely touted in the planning and architectural circles as a success, “a city in microcosm”—albeit in this case a city where working-class housing has been relocated off-site and out of sight.

[RELATED ARTICLE: After Ida, How Can Affordable Housing Withstand Climate Impacts?]

Adhering to this old economic development style—agnostic to the needs of residents of a certain class and/or race—misses the opportunity to leverage undervalued community strengths for broad-based benefits, say Hanna Love and Jennifer Vey in their policy piece “Don’t Go Back to Old Economic Development Ways.” Economic leaders have a track record of imposing actively harmful policies on communities, and are seldom held accountable, they said.

Economic injustice in housing is nothing new. The planning profession believes a collective moment of reflection is happening now, but it’s hard to prove this reflection is actually occurring, at least in Holmdel. The development plan for the South Laurel Avenue property was pitched to Holmdel with garbage pickup planned to occur only every two weeks. Yet Holmdel officials, including the township planner, never pushed back publicly. The approval of a disingenuous sanitation plan for low-income housing speaks to what the power holders in Holmdel did not state publicly: it is their choice to be insensitive to, and make reckless decisions for, those who bear economic hardships.

Planners are often the only professionals at town hall with credentials specific to the social and economic needs of marginalized populations. That’s because professional planners are certified by the American Planning Association (APA). Its AICP designation, for election to the American Institute of Certified Planners, signifies education, experience, breadth of knowledge, ethical practice, and the commitment to the planning profession, says the APA.

Planners have the professional and ethical training that requires them to voice concerns to the municipal power structure. That voice should include when housing projects run counterproductive to the well-being of human inhabitants, as much it does to the technical aspects of projects, such as rebar or support columns.

Will Planners’ Silence Contribute to Climate Gentrification?

As the community development profession touts equity-focused development and the APA revamps its code of ethics, planners should be empowered to push back on public officials who endorse bad land-use schemes. It’s unfortunate that, aside from technical queries, Holmdel’s municipal planner never publicly weighed in on the approval process for these affordable housing units. Passing the PIL structure in its public meetings, both Holmdel’s Township Committee and its Planning Board approved what amounts to climate gentrification.

The APA provides resources for planners working in the field. At the time that Holmdel targeted the commercial lot on South Laurel Avenue for low-income housing, officials involved had recourse to several APA guides and resources.

The APA’s Planning for Equity Policy Guide outlines the role of social justice and racial equity in planning. It maintains that inequity is measurable and marked by two key attributes: disproportionality and institutionalization. Disproportionality reflects amplified disparities for certain parts of a community, while institutionalization means that inequity is embedded in methodologies that justify harmful systemic policies and neglect those impacted by it. These attributes are clearly seen in the case of Holmdel’s rezoning. Only affordable housing stock, home to households with lower incomes, was selected to be built on land with a CAFRA designation. Institutionalization was expressed by selecting wetlands and flood-prone lots as sites appropriate for low-income communities and, especially, in the sanitation plan. A once-every-two-week garbage pickup schedule for a development housing hundreds of people would not be imposed elsewhere in the town. However, at least publicly, Holmdel’s elected and appointed officials were never critiqued by those in attendance at meetings, or by others in power, for perpetuating such levels of inequity as to place low-income housing on land with a CAFRA designation.

There is a more direct line being drawn by the APA between planners’ roles in reviewing types of land use and structures, and the need to advise on the implications for the humans living in and around these structures and proposed structures.

Researchers have recognized that planners today are less likely to take a political stand than they used to be. In a study by Mickey Lauria and Mellone Long, researchers examined three theories of ethics reflected in the AICP Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct: virtue ethics, which is aspirational and based on doing what is “moral,” not on how it will affect others; deontic ethics, which stresses following accepted rules; and utilitarian ethics which focuses on the outcomes or consequences of a decision. They found that most planners today conform to a technical role, in which they see themselves as a value-neutral adviser, and less to a political role, where they see themselves as advocates for specific values or policies.

“Planners as technicians in our approach lean heavily on their expertise (and therefore legitimacy) using science and objective analysis to steer clear of the supposed quagmire of plural politics and leaving democratic legitimacy to actors in the political sphere,” the study says. And because the decisions of technical planners are often based on following established rules, they may fail to intervene in cases like Holmdel where all the boxes are checked but the outcome leads to further disenfranchising historically marginalized groups such as people of color and low-income households.

“Often the decisions are made that the vulnerable neighborhoods are sacrificed at the expense of other areas,” said William J. Fritz, president of the College of Staten Island, at GIS Day 2021, a conference focused on climate change gentrification that was hosted by the college.

Joining that discussion was journalist and author Mario Ariza, who documented climate gentrification when probing the history of the city of Miami for his book Disposable City. “We live here as if we conquered nature and that’s a really problematic ideology,” said Ariza. Planners who understand the underlying issues with this “conquered nature” approach “are a bit hamstrung,” he explains. The pressure to preserve land, or to set it aside or use as a natural buffer, is nothing compared to the pressure to sell and develop property.

To Ariza’s point, while the results of climate gentrification are clear, documented, and dangerous, the fact is that climate gentrification remains political. Planners, therefore, are able to remain mute. It’s clear that climate gentrification must be treated as a technical obligation if the community planning profession expects its own experts to push back against disastrous housing proposals.

In 2018, the APA established a Social Equity Task Force to assist its members. This included tools for capacity building around economic justice, and its existence predated Holmdel’s efforts. Yet without the voice of the township planner in the public sphere, we do not know if Holmdel officials were introduced to planning concepts that take into account economic hardships, social injustice, or even climate impact. We just have the outcome: rather than build affordable housing at Bell Works, two different committees relocated the town’s future residents—the people who can least afford disaster—to lots with a known history of flooding.

The Balance of Power in Climate Change

That the affluent town of Holmdel can engage in climate gentrification should prompt reflection by the planning industry. How will its professionals handle this ever more obvious concept of climate gentrification? That certain properties become more valuable than others because of their ability to accommodate settlement and infrastructure in the wake of climate change is bound to reach and impact planning departments across all 50 states.

Will planners publicly address aspects such as who gets to inhabit the drier land? In keeping silent, they risk pointing toward who is prevented from enjoying that same protection. After all, it’s happening in real time in Holmdel, where elected and appointed authority figures have steered affordable housing away from areas of prosperity and onto properties that are flood-prone or a wetland. Or will planners continue to operate as they have done?

[RELATED ARTICLE: Deciding Not to Rebuild After Climate-Related Disasters]

The research on planners conducted by Lauria and Long lends testimony to the fact that professional planners walk a very uneven path. Sure, professional organizations can offer guidelines that promote better housing decisions but does that actually empower an individual planner? Elected officials have a short-term interest whereas professional planners should be focused on the long game. That’s where the professional community planning industry comes in. It needs to help redefine the balance of power in the era of climate change, and provide meaningful support of practitioners.

The APA, in lockstep with its members and community advocates, has the platform to empower planners to speak up about climate gentrification. Its sheer size provides cover for the fallout prompted by individual planners who raise issues of equity with development proposals. Its Planners’ Advocacy Network could be a resource for individual planners to reach out to for support when the political forces in their community resemble a destructive force. Shining a light publicly is one way to get elected officials to look to their planners for meaningful input and take their advice seriously. In the case of Holmdel, the planner was not given a role outside of non-technical aspects. Lawyers for the developer, the town, and township officials defended the plan during the public portion of meetings.

To stem climate gentrification, the planning industry should also pursue state environmental laws that give planners actual power to override terrible decisions made by local officials. Certainly few, if any, professional planners would endorse the rezoning of land with existing CAFRA wetland designation for use as low-income housing—or most any housing stock. Politically, it is feasible to envision this. Industry-wide change already exists in New Jersey’s Environmental Justice Law. Enacted in 2020, it authorizes the state DEP to evaluate siting new facilities such as power plants, incinerators, sewage plants, and others with regard to environmental and public health impacts on overburdened communities.

Steinberg of the University of Massachusetts Global holds out hope that planners will emerge to address the climate emergencies happening in their own communities. “Flooding on the East Coast is getting harder to deny.” Also, there’s a path forward. The profession, especially its up-and-coming practitioners, can stop using policy and dollars to preference the rich, she noted.

Urban planners are not the only type of professional planners that exist. Planners are not all generic. Pls respect the fact that we have capable, professional planners who are NOT “urban planners”.

Colleen O’Connor Grant has written an important article on how to reduce the impact of natural disasters on low-income housing and community development. Too often, low-income communities are built adjacent to rivers and flood plains I was leading a United Way in Central New Jersey when Hurricane Floyd struck in September 1999 and devastated the towns of Boundbrook and South Manville. It was heartbreaking seeing families dig their prize possessions out of layers of mud.

We have to do a better job of planning, preparing, mitigating, recovering, and rebuilding houses and communities impacted by an increased number of disasters including flooding, fires; drought; earthquakes; and yes toxic area from pollutants and fires. I have been working with the California Coalition for Rural Housing (CCRH) and we have come up with four major types of building efficiencies: location; design; construction; and operational. They are a number of key elements that we have learned collectively that can make a positive difference in reducing the impact of disasters.

Veronica Beaty, CCRH Director of Research, and I recently co-authored an article for Non-Profit Quarterly titled The New Normal: Natural Disasters and Affordable Housing. Sadly, natural disasters are becoming the New Normal regardless of where you live and work. We have to develop core competencies and strategies to minimize the damage to vulnerable families and communities.

Wow. I think this goes beyond climate gentrification as it is so egregiously unjust. It would be good to spotlight more nuanced situations that lead to climate gentrification. One issue is that climate change is changing the risk landscape. Not only are risks increasing in areas that already face hazards, but new areas will be at risk in the future as climate shifts. As precipitation intensity increases in some areas and/or sea level rises, some areas considered at no or very low risk today will be at significant risk in the future. Planners and others ignore these future risks by not accounting for climate change in their practice. We have the tools to forecast where these future areas of risk lie. But the effort has to be proactive to look ahead. So it is vey possible that development is being located in areas considered safe today that will not be safe in the future. It is negligent not to use the science and tools we have to plan for climate change.