This article is part of the Under the Lens series

The Racial Wealth Gap—Moving to Systemic Solutions

I wrote a similar headline for a Shelterforce article several years ago. That article was about tax programs—those that aid in the building of assets for people who already have a substantial amount of assets, and those that help people with minimal to no assets. In digging into the topic and through conversations with advocates, it became evident to me how the disparate treatment of these groups of earners by our tax code could bolster them financially or hinder their ability to avoid debt and save for the future.

U.S. tax policy has largely avoided scrutiny through a racial lens. After all, how could race be a factor when a white person earning $50,000 is taxed at the same rate as a Black person earning the same amount? But in her 2021 book, The Whiteness of Wealth, Emory University professor Dorothy Brown argues that not only has our tax code had a deleterious effect on Black lives, when it comes to racial wealth disparities, nothing, not even the racism that has permeated the real estate industry, is more systemic.

Prior to World War II, taxes were largely paid by the wealthy. Wealth at the time was inextricably tied to race and gender, and Black people were only a few generations removed from enslavement. Then and now, the tax code favored the wealthy, aiding their ability to keep more of the money they made and shield it from further taxation. This changed on a large scale with World War II, when tax rolls were expanded; the threshold of taxable earnings was lowered so that less-wealthy citizens contributed to the war effort.

This expansion became permanent after the war, and though more Black and white Americans were paying taxes, Brown explains how racial discrimination solidified a tax system that Black people paid into but could extract little to no value from. This is exemplified in the postwar GI Bill, a federal program that nearly 8 million veterans and their families benefited from. It helped cover vocational and higher education tuition, provided small-business loans, and approximately 4.3 million low-interest home loans. Though they paid taxes that were used to fund these programs, Black Americans were routinely denied access to them, either through segregationist Jim Crow laws or on the ground by banks, educational institutions, and employers.

The timing of this massive investment in white wealth was pivotal, as it came at a period of great American economic growth. Millions of white Americans were able to rise from the ranks of the poor and working classes to the middle class by leveraging free or discounted educations to get higher paying jobs, investing more capital into their business as a result of smaller interest loan payments, and leaving to their children homes they were able to afford with low-mortgage loans. None of these benefits were widely afforded to Black Americans, contributing in part to today’s stubborn racial wealth gap.

Beginning with that systemic change and covering decade after decade since, Brown details how U.S. tax policy has been tweaked to accommodate societal shifts, but only as they pertain to white Americans. She argues that these changes have been made without regard to the economic effect institutionalized racism has had on the realities of Black Americans—where they purchase homes and live, who the wage earners in their households are, and their ability to grow wealth.

The racial wealth gap is this abstract thing, occasionally made real when someone cites an intimidating, ever-increasing number. We rarely hear the stories of its individual victims, but in The Whiteness of Wealth, Brown tells the stories of real people, stories that dive into several areas that drive economic outcomes—the housing market, higher education, the job market, and generational wealth.

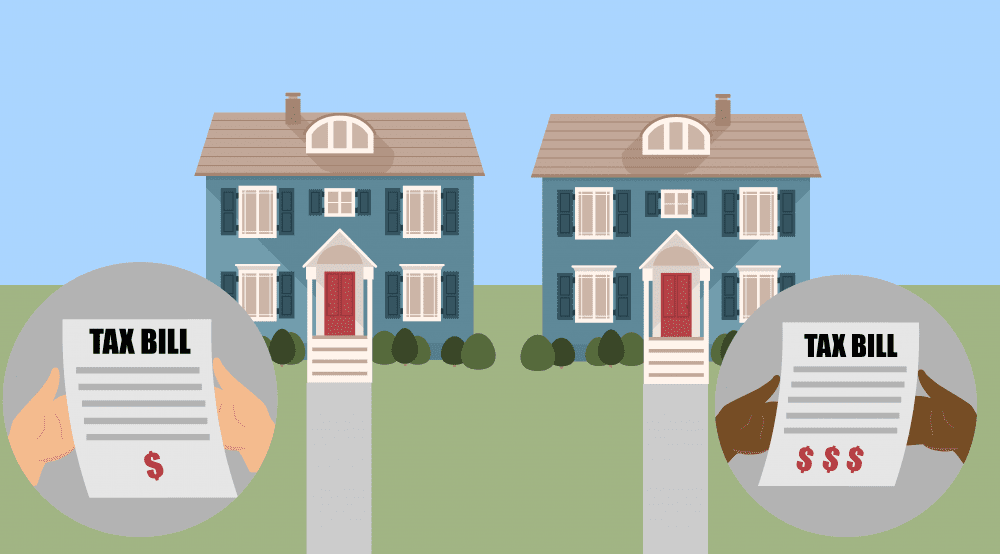

From the ramifications of redlining to the mortgage interest deduction’s favoring of higher-income earners, none of the areas Brown touches on are quite as multilayered as housing.

Brown cites research in her book that shows homeownership is the single largest contributor to the racial wealth gap. She argues that while it is sold as the way average Americans can attain and pass on wealth, homeownership has generally been a bad tax deal for Black Americans because racism disadvantages them at every step—in the mortgage application process, in where they are able to purchase and subsequently sell a home, and in refinancing to capitalize on equity they have earned.

In her author’s note, Brown recounts some of the “lucky” events in her life that played a part in her financial success—a white boss who helped her parents purchase their home, a teacher who pushed her to test into a specialized high school—to underscore the fact that many other families’ stories are similar. Their success wasn’t impossible, but it has often been achieved against the odds, and sometimes at the discretion of white people.

A recent example of how casual racism can affect Black wealth made news headlines when a couple filed suit against a white mortgage appraiser for undervaluing their home—to the tune of a half million dollars—because they are its owners. After they removed all traces of “Blackness” from the home and had a white friend pose as the owner, the home appraised for over $500,000 more than it had only one month earlier.

It’s worth noting that Brown assumes no inherent link between Blackness and lower financial status. The real-world families she profiles, including her own parents, are working people from all points on the financial spectrum, holding blue-collar and white-collar jobs. At the same time, she acknowledges that despite the wealth that has existed in (growing) pockets of the Black community for generations and the massive strides made in a relatively short time by Black people as a whole, the gains they make will continue to be insufficient because of the foundational role racism plays in our tax system.

Brown’s remedies are similar to those of Richard Rothstein, a historian and author whose book on de jure racial housing discrimination she cites in The Whiteness of Wealth (but she disagrees with him on a few points). Because discrimination on the basis of race is now illegal does not erase its effects, and so explicit harm can only be rectified with explicit remedies. In the chapter “What’s Next?”, Brown suggests publishing tax data by race, a return to a progressive income taxation system with no exclusions, a single deduction, no reduced or preferential rates, and establishment of a tax credit for Black Americans that would compensate for their economic losses as a result of institutionalized racism.

It seems unlikely this is in our near future, as even the passage of voting rights bills is out of reach. But as fair-minded people continue to advocate for tax law changes, Brown shares tips for Black families to retain more of what they earn. No matter the income, that is key to being able to turn money into long-term investment and wealth.

Perhaps controversially, Brown also suggests one investment Black people may want to prioritize over homeownership, leading me to think the book’s only failing may be our inability to get it into more people’s hands.

|

Help keep us strong by becoming a Shelterforce supporter. |

I, too, found the book helpful and a unique approach to explaining the wealth gap that should get more exposure. I also appreciate her argument that calls for greater homeownership rates for Blacks are misdirected if the systems of discrimination/racism that limit the value appreciation of Black-owned property remain in operation.