This article is part of the Under the Lens series

The Racial Wealth Gap—Moving to Systemic Solutions

Photo by Andrii Yalanskyi via iStock

State and local property tax relief programs for homeowners can provide significant cost savings and other protections for a homeowner’s primary residence, also known as a homestead. But many of these programs disproportionately exclude Black and Latinx homeowners, resulting in their having higher tax burdens, eroding their housing stability, and contributing to our country’s vast racial divides.

Take, for example, an elderly homeowner residing in the Cedar Crest neighborhood of Dallas—one of the few neighborhoods in Dallas where Black families could purchase homes prior to 1965. Many of the homesteads in Cedar Crest, including this homeowner’s residence, have been passed down to family members via inheritance, a pattern found in similar majority-Black neighborhoods across the country.

Because the Cedar Crest homeowner inherited her homestead with other family members, Texas laws until recently limited her access to state-authorized property tax relief programs for seniors—resulting in an annual tax bill for this homestead of $2,117. If this home had been purchased instead of inherited with family members, the annual tax bill on the homestead would have been only $11. Without that support, the homeowner missed many property tax payments, and the property tax debt on the homestead, including fees and interest, had grown to $8,000 as of 2020, making her highly vulnerable to property tax foreclosure.

An Overview of Property Taxes and Tax Relief Programs

Property taxes are the primary source of tax revenue for local governments in the United States, particularly counties and school districts. Property taxes are usually administered at a local level, but most states impose restrictions on how local governments may tax property.

Property tax bills vary widely across the U.S., depending on the assessed values of homes, tax rates, and property tax relief programs available to homeowners. Single-family homeowners in the U.S. pay an average of $3,719 in property taxes a year, with the median property tax bill on all owner-occupied homes in each state ranging from $587 in Alabama to $8,362 in New Jersey. Those with the highest property tax burdens are far more likely to have low incomes: Of the homeowners who pay more than 20 percent of their income in property taxes, more than 9 in 10 make less than $40,000.

To help homeowners with their property taxes, every state in the country and many local jurisdictions have adopted one or more property tax relief programs for homesteads. Some tax relief programs are available on the primary residence of all homeowners, while others are restricted to the homesteads of certain groups of homeowners, such as lower-income, elderly, or disabled homeowners.

At least 46 states and the District of Columbia provide tax relief in the form of a homestead property tax exemption or credit. Together, these programs delivered an estimated $16.2 billion in annual property tax savings to homeowners in 2012, according to the most recent data available through the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy’s property tax database. Many states also provide lower property tax rates and assessment ratios for owner-occupied homes or a broader category of residential properties, as compared to other classes of properties such as commercial buildings.

According to the Lincoln Institute’s property tax database, 27 states and the District of Columbia also offer protections for homeowners who fall behind on their taxes through homestead tax deferral programs that provide a safeguard from foreclosure. A number of states also offer grant and loan programs to assist lower-income homeowners with their property taxes to avoid foreclosure. And almost a third of states and the District of Columbia offer some form of “circuit-breaker” program that helps lower-income, and sometimes moderate-income, homeowners by providing a reduction or refund of all or a portion of their property taxes when the tax bill on their homestead exceeds a certain percentage of their income.

Property tax relief programs can reduce a homeowner’s property tax bill by thousands of dollars per year, depending on where the homeowner resides. Researchers have found that these programs ultimately increase the housing stability of homeowners who are financially insecure by reducing property tax default and mortgage default rates.

In Houston, for example, as a result of the various property tax exemption and tax freeze programs on homesteads with a senior homestead exemption, the tax bill for a homeowner who is 65 or older with a home appraised at $100,000 can be as little as zero, with annual tax savings of over $2,300. If the homeowner falls behind on their taxes, they also have the right under state law to defer payment of their property taxes with interest as long as the home remains their primary residence. Deferrals are available through an application with local tax office, and while one is in place, taxing authorities are barred from foreclosing on the homeowner.

How Property Tax Relief Programs Exclude Certain Homeowners

In the midst of a project I was leading on housing displacement in 2018, our research team learned something troubling from an attorney in our local legal aid office: Homeowners who inherited their homesteads in Texas were often unable to access the full benefits of the state’s homestead exemption for property taxes. For these highly vulnerable homeowners, being barred from these benefits meant higher property tax bills and, for some, the loss of their homes to property tax foreclosure.

Homes that have been inherited are a form of heirs’ property, where multiple relatives often end up co-owning a home, farm, or other real property together. One or more heirs may reside on the property, or the property may be leased or unoccupied. Heirs’ property is particularly common in older lower-income communities, both rural and urban, including areas where multiple generations of Black and Latinx landowners have resided. By excluding homeowners who inherited their homesteads, property tax relief programs are also likely disproportionately excluding Black and Latinx homeowners.

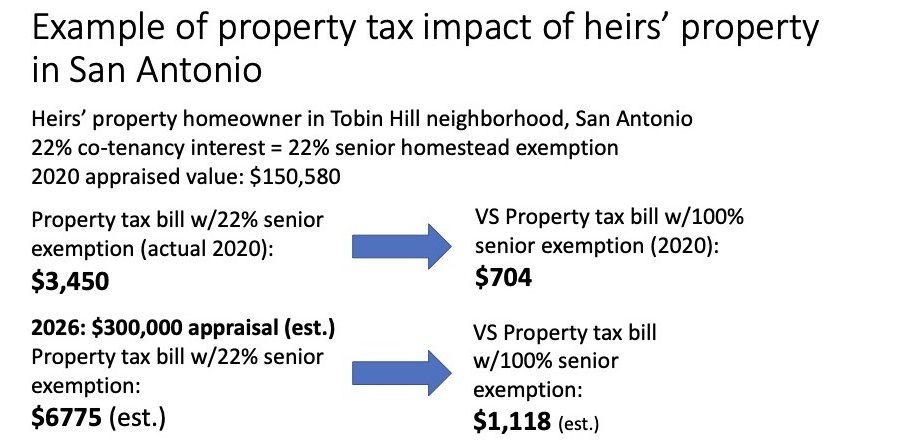

Our research so far has confirmed these disparate impacts in Texas. For example, in Bexar County (where the city of San Antonio is located), we found that seniors who inherited their homesteads are largely concentrated in very low-income communities of color within the urban core of San Antonio. As a result of a Texas law that restricted heirs’ and other co-owners’ access to the senior homestead exemption based on their co-ownership interest, these seniors owed an average of $1,157 a year in additional property taxes compared to what they would pay if the property was not co-owned or if the law had provided them with full access to the senior homestead exemption.

Slide courtesy of American Bar Association

What was happening in Texas turns out to be common in other states as well. Similar to Texas, many states reduce the amount of a tax break that a homeowner can receive on their homestead based on the homeowner’s co-ownership interest in the property. If a homeowner has inherited a 10 percent co-ownership interest on their homestead, they can qualify for only 10 percent of the homestead exemption—even if the homeowner is paying all the property taxes on the home. Heirs who are senior citizens or disabled and fall behind on their property taxes also cannot rely fully on a state’s deferral law to save their home from property tax foreclosure.

A number of other states bar a homeowner with heirs’ property from qualifying for property tax relief unless all the heirs use the home as their primary residence and meet all of the program’s other eligibility requirements. In New York, for example, the senior citizen homeowners’ exemption, upon adoption by a municipality, reduces a home’s assessed value by up to 50 percent when the home is owned and occupied by a qualifying low-income homeowner. But the homeowner is disqualified from accessing the exemption if the home was inherited and one or more of the co-owners reside elsewhere. And even if all the heirs reside in the home, the homestead is ineligible for the exemption unless all the heirs are 65 or older, with an exception for instances in which the heirs are siblings or spouses. In other words, if two cousins have inherited the home where they reside and one of the cousins is under 65, the home is completely ineligible for the exemption.

On top of states providing diminished property tax savings on homesteads for homeowners with heirs’ property, we also discovered in our research that many states require homeowners to have a deed or other form of legal titling instrument that is recorded in the real property records in their name in order to qualify for any tax savings. Homeowners who have purchased their home can easily satisfy this requirement because a deed is at the heart of a home purchase transaction and is typically recorded by the attorney or other professional who oversees the closing on the home (with the exception of certain types of seller-financed transactions).

In contrast, a recorded title requirement is a high bar for many people who have inherited their homes, particularly when the prior owner died without a will. While the exact procedures vary across states, individuals who have inherited their home without a will typically must follow a set of lengthy, complex, and often costly legal procedures in probate court to obtain a deed. For homesteads that have passed down via inheritance across multiple generations without a will—an especially common practice in older African American communities—obtaining a recorded title as an heirs’ property owner is even more complicated and expensive.

Even if an heir can obtain a deed after inheriting the family homestead where they reside, lengthy probate procedures often cause the heir to lose any preexisting property tax exemptions on the home in the process of waiting for the probate and titling process to be completed. The increase in property taxes during this lag time can create severe financial repercussions for low-income heirs.

Of the 24 states we have examined so far, only two—Mississippi and Texas—have adopted statutory criteria as of 2021 that explicitly allow heirs to qualify for the state’s property tax relief programs on their homesteads even if they are not listed as the grantee on a deed or other recorded legal instrument for the property. Eleven of the other states in our study, along with the District of Columbia, require a deed or other recorded legal instrument transferring title to the tax relief applicant, with two states allowing for a recorded affidavit of heirship as a substitute for a deed. The other states have a patchwork of eligibility criteria at the local level, also resulting in barriers for heirs who lack clear title.

An example of these barriers can be found in Florida’s general homestead exemption, which provides annual property tax savings as high as $1,500 for a homestead with an appraised value of at least $75,000, depending on the local tax rate. To qualify for the exemption, state law requires that an applicant’s ownership interest be recorded in a deed or similar legal instrument. Homeowners who apply for the state’s 100 percent homestead exemption for low-income seniors must also meet these stringent proof-of-ownership requirements.

Similarly, Georgia state law requires applicants for the state’s homestead exemption to have a deed in their name prior to filing the application. When a home passes to one or more heirs residing in the home, any homestead exemptions that were on the homestead are removed until a new deed is filed, which can saddle the heirs with a large increase in property taxes.

Additional Inequities in Property Tax Relief Programs

Researchers have identified several other issues that result in lower participation rates in property tax relief programs among Black and Latinx homeowners, including lack of awareness about the programs and application hurdles. While some property tax relief protections are automatically applied to a homestead by the tax assessor, most require that homeowners affirmatively apply for the program. Some jurisdictions require an annual application, while others require only a one-time application, either in person at the tax office, online, or by mail, depending on the jurisdiction.

For example, one study from Chicago found that 40 percent of older homeowners with a home equity conversion mortgage loan did not participate in a senior tax relief program they were otherwise qualified for, with Black and Hispanic homeowners less likely than white homeowners to participate. Failure to participate in the tax relief program was associated with an increased probability of property tax default. Another study, this one from Florida, found that, on average, 15 percent of homeowners in majority Black neighborhoods did not participate in the state’s homestead exemption program, compared to 9 percent of homeowners in majority white neighborhoods.

Taking Action

Fortunately, there is much that advocates can do to confront these disparities and make property tax relief programs in their community more accessible and equitable.

Identify the Barriers

First and foremost, understand how property tax relief programs operate in your community, who is barred from accessing these programs, and why. From my experience, legal aid attorneys who help low-income homeowners when they fall behind on their property taxes are often already familiar with what these barriers are. Partnerships with university researchers can also help identify these access barriers. From our initial research discussed here, we already know that many states have property tax relief laws that exclude homeowners who have inherited their homes.

Legal Reforms

Second, in many communities, local or state legal reforms may be needed to make tax relief programs more equitable. While having to reform a law may sound daunting, know that reforms may garner broader support than you anticipate and, ultimately, may not be that difficult to adopt.

In 2019, after learning about the barriers in Texas for heirs to qualify for a homestead exemption, my law students and I drafted state legislation to fix these barriers. We did not think the reforms would go far, but they were ultimately met with widespread bipartisan support in the Texas Legislature. The conservative chair of the Texas Senate Committee on Property Tax became one of the biggest champions of the legislation. Just three months after the legislation was filed (as Senate Bill 1943), it was passed by the Texas Legislature and signed by the governor.

With the legislation, Texas became one of the first states in the country to provide clear and accessible standards for how homeowners can qualify for property tax relief on their principal residence when they have inherited their home and lack a recorded title instrument. Texas law now allows an heir to submit a simple affidavit to establish proof of ownership for purposes of qualifying for a homestead exemption when an heir is not specifically identified as the owner on a deed or other recorded instrument. The application requirements for heirs are spelled out in the instructions to the exemption application, and the affidavit is included in the application. The legislative reforms also provide heirs with full access to the residence homestead exemption rather than limiting access based on the heir’s ownership interest.

For current homeowners with heirs property, these full tax savings are only available, however, by filing an updated homestead exemption application. As of 2021, the homeowner in the Cedar Crest neighborhood discussed above had not filed an updated application to access these benefits.

Community Education

Third, community education is critical. In Texas, after the reforms to the state’s property tax relief programs were adopted, we first focused our efforts on educating legal aid offices about the reforms. We then heard from legal aid lawyers that many local tax appraisal districts were not following the new law. We confirmed this with a survey of appraisal districts. In response, we ended up putting together a webinar for the appraisal districts on the reforms along with mailing all of the appraisal districts educational materials.

Educating homeowners about how to qualify for property tax relief programs is just as critical. There are lots of models for how this can be done, but one of my favorites in Texas is the HECHO project in San Antonio; HECHO stands for Homestead Exemption Community Housing Outreach. Through HECHO, staff from Texas Rio Grande Legal Aid, neighborhood groups, and other community partners have been conducting door-to-door outreach to homeowners without a homestead exemption, using lists provided by the local tax appraisal district. The outreach workers educate homeowners about the benefits of the homestead exemption and assist them with the application on the spot.

I have also worked with the Texas Comptroller, local appraisal districts, and self-help organizations to put information on their websites about how heirs can qualify for a homestead exemption under the new state law. Much work remains to be done in terms of educating homeowners about the new law, as many homeowners with inherited homesteads have still not filed the necessary updated application to secure full access to the state’s property tax relief programs.

Through fairly simple legal reforms, coupled with community education and better training of taxing entities’ staff, property tax relief programs for homesteads can become more accessible to Black and Latinx homeowners, resulting in lower property tax burdens and greater housing security. Understanding how these programs operate and eradicating their discriminatory impacts is critical to creating a property tax system that is fair and equitable and to closing our country’s racial wealth gap.

Parts of this article are excerpted from the chapter by the author, “Heirs’ Property, Property Tax Relief, and the Further Undermining of Black and Latino Homeowners’ Housing Stability,” appearing in Heirs’ Property and the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act: Challenges, Solutions, and Historic Reform (Thomas W. Mitchell and Erica Levine Powers eds., American Bar Association), forthcoming in 2022.

|

Help keep us strong by becoming a Shelterforce supporter. |

Comments