Photo by Flickr user Jill Chanapai, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

If you couldn’t afford your rent, where would you go for help? In most American communities, that simple question has no obvious answer. Federal, state, and local rent assistance is provided by multiple nonprofits and government agencies in each municipality, each with its own eligibility rules and ways to apply. The messy housing assistance system in the U.S. is one of the main reasons COVID-related rent assistance has been extremely slow to be spent. A full overhaul is needed to avoid future housing crises.

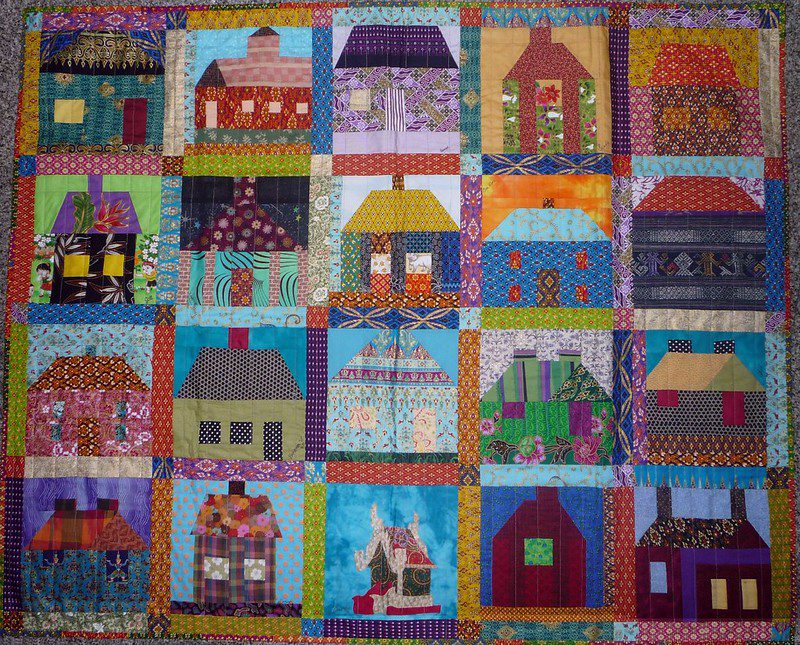

A Patchwork of Housing Assistance

Housing assistance is currently administered in the United States by a confusing patchwork of agencies, each with its own geographical boundaries, plus targeted programs with their own eligibility criteria. This system makes it difficult for people to access resources, creates inequities between jurisdictions and populations, and prevents effective rollout of nationwide policies or funding like the COVID-19 Emergency Rental Assistance (ERA).

Rental assistance provided by local housing authorities makes up the lion’s share of housing assistance in the U.S., but receiving help from your local housing authority is far from simple. Many areas are served by multiple, sometimes dozens of housing authorities. In the Boston metro area there are 94 housing authorities. Once you find your housing authority, you may find that due to lack of resources there is a wait list. Housing authorities have broad flexibility on how to maintain that list, including giving certain groups, such as people with disabilities or people experiencing homelessness, preference for the next available slot. Housing authorities whose wait lists are very long may stop taking new applications altogether.

Whether assistance is available to any particular person is determined by a complicated equation of the resources their housing authority has, the way that housing authority operates its wait list, and what targeted groups that person falls into. People in communities right next to each other may have very different access to resources.

Housing authorities are not the only game in town, but other sources of rent assistance are much smaller than the housing-authority-run programs, administered by myriad local agencies, and generally targeted to special populations. HUD’s Continuum of Care and Emergency Solutions Grants (ESG) programs provide rent assistance (as well as emergency shelter and other services) to people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. Each community sets up what is called a Continuum of Care (CoC) to oversee these programs. Each CoC defines its own boundaries, chooses an agency to lead it, and decides which agencies receive funding. As with housing authorities, some CoCs are regional while some are hyperlocal. And like housing authorities, CoCs have broad flexibility to set local preferences for targeting their resources and sometimes have special resources that other CoCs do not have.

Veterans who are experiencing homelessness or housing instability can access another system of housing assistance run by the VA. Someone experiencing homelessness who is living with HIV has another housing option, called Housing Opportunities for People With AIDS (HOPWA). HOPWA is generally administered by local or state government. There are also affordable housing properties that people can apply directly to; each property generally runs its own wait list with its own eligibility criteria.

To make matters more confusing, the USDA also funds affordable housing properties in rural areas, and FEMA provides rental assistance after people are displaced by natural disasters.

Other assistance systems are not set up like this. Everyone knows what to do if they can’t afford health insurance: apply for Medicaid if you’re young, Medicare if you’re older. The Affordable Care Act set up one-stop application and shopping for health insurance for people across different levels of need. The same goes for food assistance: if you need help paying for food each month, you apply for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, informally known as food stamps).

The patchwork nature of housing assistance makes applying for help confusing and makes it difficult to create a nationwide expeditious response to a crisis.

Scarce Resources

There are many reasons this non-system of housing assistance exists today, but it persists largely due to an extreme lack of housing assistance resources. Only roughly one in five renters who is eligible for federal rental assistance actually receives it. Over 7.5 million low-income renter households paid more than half of their income toward rent in 2017. There are millions of renters on the brink of eviction at any moment, and housing authority wait lists are years long. This mishmash of housing assistance with complicated eligibility rules and many gatekeepers limits the housing problem in America to a size that is somewhat manageable for each program. We wouldn’t need a specific housing program for people living with HIV if housing assistance was generally available to everyone, but since it isn’t, HOPWA was created to help this particularly vulnerable group.

In contrast, everyone who is eligible for Medicaid receives it. The arguments about Medicaid expansion focus on whether to expand the eligible group, not on simply providing enough money to help those who are already eligible.

[RELATED: Universal Housing Vouchers: A Promise or a Pipe Dream?]

It’s worth diving into some nitty gritty budget issues for a moment. Unlike other safety net programs (Medicaid, Medicare, SNAP), housing assistance is on the discretionary side of the federal budget ledger. That means the total amount available for the HUD budget (and the USDA and VA rental assistance budgets) is approved by Congress every year. During the budget process Congress sets an overall amount for all discretionary programs, then divides that amount into budgets for each area of appropriations (called 302(b) allocations in the parlance). Housing funding lives in a dog-eat-dog, rob-Peter-to-pay-Paul world, in which one more dollar for housing may be one less dollar for Amtrak, for instance. Of course, Congress could just increase the total amount available for discretionary spending enough to guarantee housing assistance for all, but at least in the last 10 years, there have been binding caps limiting how much discretionary money is available. Although it is possible to provide funding for everyone who needs housing assistance within the current budget structure (and the current federal budget resolution takes a big step in that direction), the better solution would be to fund housing assistance on the mandatory side of things (either mandatory spending like SNAP or as tax credits like the ACA premium tax credits) so Congress doesn’t have to re-up funding every year.

Ramping Up Housing Assistance During COVID

Congress greatly increased housing spending in response to the economic and public health crises caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The $46 billion available for eviction prevention (called Emergency Rental Assistance or ERA) alone is about the same amount as the whole annual HUD budget, and the individual programs within the HUD budget also got bumps in pandemic relief bills. Our fractured system was not ready to expand its capacity that quickly.

The largest challenge facing ERA is that there was no pre-pandemic nationwide eviction prevention funding. Although eviction prevention is an allowable use of ESG, due to the extreme lack of resources, most communities use ESG to help people already living on the streets. VA programs conduct some eviction prevention as well. Very few municipalities or states were funding eviction prevention on a large scale before the pandemic. To put it in perspective, the total amount of funding CoCs administer annually (CoC and ESG programs combined) reached $3 billion in FY2021. Although much attention has been paid to the $46 billion in ERA, the CARES Act provided almost $4 billion to the ESG program, effectively doubling the size of the homeless assistance system.

[RELATED: How Santa Fe Prevented Evictions with Easy Access to Rent Relief]

Shoestring nonprofits found their budgets ballooning while they struggled to figure out how to keep their current staff and clients healthy. The ERA funding went to states and municipalities, which was a good idea because they could handle that amount of funding, but in many areas, the only people with experience running eviction prevention programs were those working in homeless assistance, already struggling to spend the additional funding they received through the CARES Act.

States, some with little experience administering rental assistance, had to create programs from scratch at scales never before seen in housing. The housing assistance system is set up to limit the number of applications to a manageable level, but suddenly states and municipalities had to figure out how to set up a system that acted more like an entitlement program.

It is no wonder that housing assistance during COVID has been delivered exceptionally slowly. This inability to ramp up during a disaster is not true for other safety net programs. During natural disasters SNAP becomes available to a larger swath of people in the affected area (known as D-SNAP), and states and municipalities are highly experienced in administering this short-term program ramp-up.

Solutions

Much has already been written about how to mitigate the eviction crisis brought on by COVID-19 and what new polices are needed to avoid future housing disasters. Good ideas include rental registries, the right to counsel for eviction proceedings, tenant-owned housing co-ops, permanent conversion of hotels for housing, and others. I am adding to this discussion that the organizational infrastructure that administers housing assistance needs an overhaul as well. I am not trying to provide the full prescription here, but hopefully I am providing some useful ideas to start the discussion.

It should go without saying that more housing assistance is desperately needed, not just during the pandemic, but for the foreseeable future. A single universal rental assistance program would go a long way to simplifying the system. Rental assistance for anyone who qualifies would drastically reduce (though not eliminate) the need for emergency housing assistance in the next economic downturn since low-income families would generally be paying an affordable amount toward rent. This funding should be coupled with a permanent large-scale eviction prevention and housing stability program that would stabilize people who have shorter-term needs. This program would be able to ramp up its services during economic downturns or other crises. The Opportunity Starts at Home Campaign lays out a very good framework for these types of ideas.

Although more robust housing assistance funding would go a long way toward helping everyone in need, it is not enough to simply expand the current system. A universal system should not just be universal in funding, but universal in the sense that the program is administered consistently across the nation. The level of customer service received, ease of application, troubleshooting when necessary, and everything else that goes into administering a large public assistance program needs to be consistent across the country. Simply expanding the current jumble of housing authorities, Continuums of Care, and smaller targeted programs would create inequities in access that could prevent people from receiving the help they need, even if the funding were available. Indeed, that has been the case with housing assistance during COVID-19.

Below are three suggestions to restructure the housing assistance system to make it more equitable, accessible, and efficient.

- Consolidate program geographical boundaries as much as possible.

The relatively arbitrary geographic jurisdictions of housing authorities and Continuums of Care pose barriers to accessing and administering rental assistance programs. There are two separate problems facing the administration of these programs. In metropolitan areas, there are usually multiple housing authorities and CoCs administering programs, often delineated along smaller municipal or county lines. But housing markets are metropolitan, and people move frequently around metro areas. Having multiple administering agencies in one metro area makes it difficult for residents to use their assistance and for the metropolitan area to have uniform housing assistance policies.

In rural areas, there is a different problem. In non-metro areas, housing authorities and CoCs are sometimes so small they can barely pay for enough staff to run their programs. These programs have the hardest time expanding to respond to emerging needs — even a small increase in funding could require a large increase in their workforce.

One option would be to consolidate all programs up to the state level and set new rules for statewide program administration. On-the-ground offices would still be needed, so states could use existing structures, like departments of social services, or contract with local agencies.

A less drastic option would be to require each metropolitan area to have just one PHA and one CoC, or possibly one housing agency that administers both. All non-metro areas would be consolidated into networks similar to the CoC system’s Balance of State concept, administered by the state government. These Balances of State would be staffed by states and have regional centers that coordinate services on the ground. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities published a report in 2016 with suggestions on housing authority consolidation. HUD has been urging CoCs to consolidate in ways similar to those I have suggested, but there is not a comprehensive document suggesting a new CoC map.

Consolidation of housing authorities and CoCs would also make crisis assistance much easier to roll out by guaranteeing rental assistance administration experience in every state and eliminating agencies that are so small they are unable to quickly expand capacity.

- Provide true one-stop application systems for housing assistance.

If simplification and consolidation of housing programs is not possible in the short term, states should at least be provided the funding to run one-stop housing assistance application systems. These systems should be accessible statewide (at least online and by telephone and have robust translation and disability-related services) and provide applicants real-time information about what they are eligible for and how to receive the assistance. Importantly, as we saw with the launch of healthcare.gov, a well-run one-stop shop is not done cheaply, so Congress must provide the funding to make this successful. FEMA should also be required to use this system for their applications after major disasters.

- If universal vouchers are provided, refocus and expand targeted service programs.

Targeted rental assistance programs, like HOPWA, were created to direct scarce resources to the most vulnerable people and to provide the targeted services each group needs. Rental assistance administration mostly takes the same skills across all populations, while services can differ greatly. It would be much more efficient to have one agency in each state that administers rental assistance and allow the agencies that currently run targeted housing programs to focus on the services their populations need.

This model already works well for veterans. In providing supportive housing (housing assistance coupled with services) for veterans with disabilities, the VA provides the services, and the rental assistance comes through the local housing authority. Although some consolidation is possible without universal vouchers, targeted programs are important in a world of scarce resources, so dissolving targeted rental assistance is only a good idea if vulnerable groups would be guaranteed assistance in a general-population program. Targeted services funding should also be expanded in a world of universal housing assistance, since more people with special service needs may be served with newly expanded rental assistance and they should have the same access to services as those enrolled in previous smaller programs had.

The COVID-19 crisis has laid bare the inadequacies of the United States’ housing assistance system and put housing assistance at the top of mind for many Americans and elected officials. If elected officials are serious about expanding rental assistance now and in the future, they must couple expansions with reforms that would make the system easier to access and better able to respond to future crises.

I really enjoyed this analysis, but I disagree on one things.. The problem of multiple CoCs covering metropolitan areas is not universal. In states with large rural populations the problem is exactly the opposite, and the Balance of State system has not been an adequate solution for the communities in these states. Better guidance from HUD on administering a regional system would be helpful, as well as more funding for staffing a regional system. What would it take to require states to administer the Balance of State system, rather than relying on non-profits?

I haven’t read this for I am currently and deemed disabled by the government.I have 20 impairments due to Covid Pneumonia,Sepsis,Hypoxia.I been waiting in the San Joaquin County,since last year,while living with my disabled partner in a old RV on the street.Waiting for Emergency Disabled Transitional housing.I have severe memory loss, and other major issues We both do.She had it harder,as I’m the one who is greatly disabled,Wheelchair bound.My partner is soon to be.We have a no experience Social Worker in our case.We are working with Section 8,they never contact us.I need to find a go to some other agency or find another Social Worker. Your information here is very insightful.Two ex professionals,who are trying to survive in a RV.I have so much medical issues,I need to find a great Social Worker or Case manager.,that can lead and have a broader resource go to plan.These young Social Worker Women ,who literally have our lives in their actions,is anxiety,fear, worried is too much for two 57 year old disabled couple.This comment took me a long time to do,just desperate in Stockton,ca