This article is part of the Under the Lens series

A home that was renovated thanks to the Family Village project in Newark, New Jersey. Family Village is rehabilitating more than 50 abandoned scattered-site properties into more than 100 safe and healthy affordable homes. Photo courtesy of New Jersey Community Capital

Hanaa Hamdi is the director of health impact investment strategies and partnerships at New Jersey Community Capital, the state’s largest CDFI. Michellene Davis is the executive vice president and chief corporate affairs officer at the New Jersey–based health system RWJBarnabas Health. Both organizations have for some years understood that the intersection of health and housing is crucial, and for the last several years they have been working together on a project in the city of Newark called the Family Village. Together they have acquired a swath of abandoned or foreclosed homes, and are renovating them to healthy homes standards. The houses will be affordable for local families who are currently unable to afford healthy homes. Residents will be connected with nonprofits including the South Ward Children’s Alliance for supportive services. Shelterforce spoke with Davis and Hamdi about what it was like for a hospital system and a community development financial institution to work together on a project like this, as well as about addressing systemic racism in health care.

Miriam Axel-Lute: What did the very beginning of your partnership look like, and how did you build support for it inside your organizations?

Michellene Davis is the executive vice president and chief corporate affairs officer at RWJBarnabas Health in New Jersey.

Michellene Davis: Our conversation probably began a year in advance, and then [we] had to come back together a year later because our first conversation was actually as I was creating our social impact and community investment practice. I needed a little bit of time.

The strategic tension inside organizations is so much more deadly to an initiative like this than external [factors]. I call it the “natural strategic tension” because it’s another way of saying everything from “implicit bias” to “individuals who have always done things a certain way, and have been successful at those things, so why would they change now?” to trying to turn a large-scale ship like ours to better understand that nonprofit community benefits—Schedule H of your 990—is not enough!

Leaders inside institutions come from a very different place, oftentimes. I had one person in treasury, on a totally different initiative, who said, “Why would a hospital system ever do this?” I have to make the business case [and] the moral case, all the time. It’s an [important] part of the success of this [to] have an external partner who can understand and weather that process with you.

Hanaa Hamdi is the director of health impact investment strategies and partnerships at New Jersey Community Capital.

Hanaa Hamdi: It took close to about a year or so in conversation on the board [to get them on board with a health equity focus]. That conversation was, “Oh, yes. Health is great. Health equity is great.” But what does [it] mean to actualize that word? How does it change our processes, the way that we provide our services to the community? We really have to go outside of what feels comfortable. We had to be patient with our board. Obviously [it’s] not as big as RWJBarnabas, but the challenges are similar. The promise that “This is for the community” is what kept us being insistent and persistent.

Harold Simon: Were there opportunities for each of your organizations to help the other make the case?

Davis: Yes, Definitely. I’ve lost count of how many times. [When] they first came to see me they talked with me for some time. Then I had to get them in to meet with the CEO at least twice, and then a member of our corporate board, and then [they] had to really go on the internal tour.

It is always a challenge, especially because this is foreign to us. We had not partnered with CDFIs before. I had to point our institution in the direction of Dignity Health—which really does a lot of work in that space, almost acting as a CDFI and working with CDFIs—in order to say, “Listen, this is new to you, and new to this state, but this is definitely something that exists nationally, [and] that we should be pursuing.” NJCC had to come in and sell it, over and over again. The fact that they were willing to do that was a very big deal.

Simon: Dignity Health has really identified this work as “investment,” and you are talking about moving beyond the community benefits model. Expand on that thought.

Davis: Absolutely. That is exactly why the name of our practice is “Social Impact and Community Investment.” When you’re dealing with hospital CFOs, [there’s] no marginal mission. It’s always like, “Is that going to be revenue-producing?” This work is not.

They had to hear from the external party about their own demonstrated track record, the projects that they’ve successfully accomplished, and their referral list. Those things were really important.

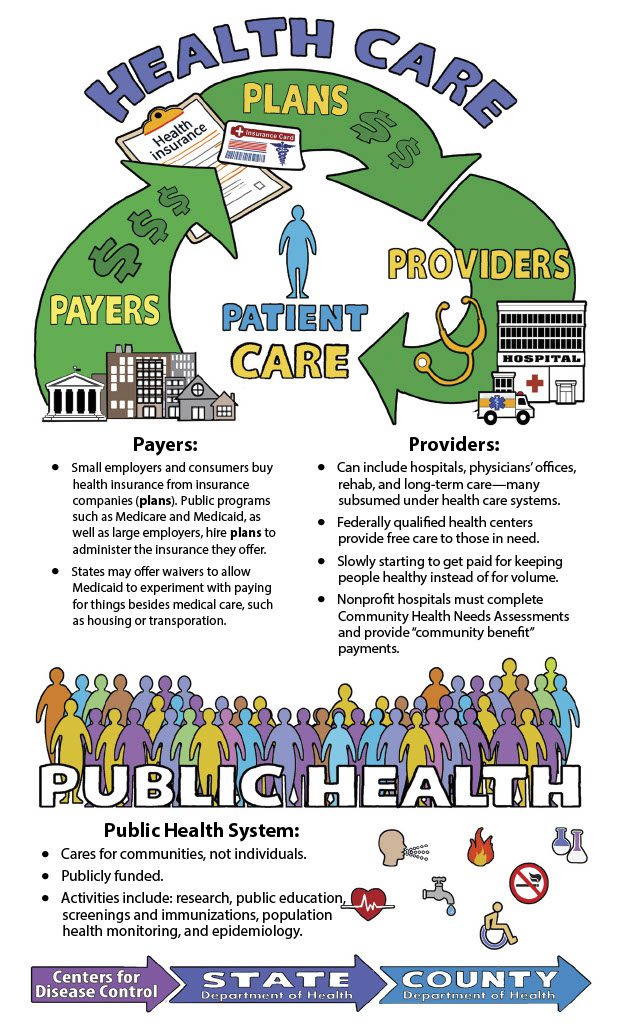

Hamdi: At the same time that Wayne [Meyer, president of NJCC] was working with Michellene and RWJBarnabas, internally we were pulling national data to demonstrate how nonprofit hospitals can invest in housing, in food, in early childhood education. That means learning public health language. There needed to be a translation from public health to community development, two sectors that work together in communities, often addressing the same issues, but speaking different languages, and measuring their impact differently.

Axel-Lute: How did you talk about public health with the community development folks and vice versa?

Hamdi: “The investment is for a patient population that has diabetes,” versus “investment in [the] whole community.” We don’t necessarily invest in housing to address diabetes. But we address the social determinants that cause these concentrated clusters of diabetes, and other comorbidities, in this community.

Social determinants are interconnected, and they’re simultaneously acting. If you invest in affordable housing, then you [also] need to invest in a food co-op: Housing, food, job opportunities, creating neighborhood financial health. It is complicated. That conversation, internally, was about six to eight months. We’re still learning.

Michellene mentioned that it took about a year. I’ve been in this business of connecting community development and health care or public health for the last 15 years. After the ACA [Affordable Care Act], the average amount of time that a hospital [takes to go] from grant-giving to community benefit [investing] is about 24 months. It is quite astonishing to hear Michellene say, “You know, we did it in about a year.” That’s amazing! Other partnerships that we have in New Jersey, we’re still trying to convince hospitals how to really use the Community Health Needs Assessment to actually change the environment. In that sense, RWJBarnabas is light-years ahead, both in New Jersey and beyond.

Axel-Lute: Did you start from “We need to partner, we need to get everybody on board” before you started figuring out the details of the project, or did you show up and say, “We want to do this specific project; let’s do it together”?

Davis: It may have been a combination of the two. Certainly, Wayne came to us with a concept, and certainly, as we talked through it, the concept began to have more of its flavor, more of the texture. I feel like we were building that plane as we were flying it. The fact that we had to go away for a year and then come back actually gave us some time to talk about what those goals look like, what would we be measuring, how can we ensure healthy homes, what does that constitute, how are we going to ensure that we’re looking at lead-free paint, but also lead-free pipes…

I think that all of that made for a richer soup, because none of it was predetermined. We got to put into it what we would need for the project that we really wanted to be able to do together.

Our anchor-mission strategy is “hire/buy/invest local.” For other anchor institutions in the City of Newark, one in particular, theirs is just “live local.” We didn’t adopt “live local,” because I kept wanting to know how does the fact that our corporate employees now live in this environment [make it] better for Miss Sadie and the neighborhood? What have we done for them by simply incentivizing folks to live there? I understand bringing a varied socioeconomic base, but we can go about the business of doing that without committing any gentrification, shoring up the lives in this neighborhood because these lives are worthy, ensuring that they have the community that they’ve always wanted to have, and acknowledging the historical disenfranchisement and zoning and regulatory ordinances that have created the health care inequities that we see.

There was a lot of mutual understanding [between RWJBarnabas and NJCC] at that level. Anything from that point was just going to be gravy.

Axel-Lute: Can you point to things about the project details that had to be adjusted from the original vision in order to support the realities of what RWJBarnabas as an institution was up for?

Davis: I don’t know that there had to be changes made as much as [Wayne] had to spend a lot of time getting them to understand the financial modeling, to really help folks who do not do this kind of financing better understand that the risk was minimal. Hospitals are very low-risk and they’re very low-risk for all of the reasons that you might possibly imagine. What we do really is life and death. But then beyond that is the additional element that we are always pretty thin-margined, that [we] have to have a certain amount in reserve.

You’ve seen a lot of health care systems across this country, even pre-COVID, close. From COVID, you’ve seen the furloughs, and the closures across the country. I just saw Georgia had seven hospitals close in the middle of being a hotbed for the pandemic. That’s just scary. As a result of that, we’re naturally risk-averse.

Axel-Lute: What would you recommend to others in your sorts of institutions who are interested in creating this kind of working relationship?

Davis: If I were talking to another person in the health care system who hasn’t entered into this space as of yet, one, there’s an organization called the Healthcare Anchor Network [that] enabled us to pair individuals who were industry asset leaders together.

[Related: Outside Their Comfort Zone: Health Sector Players Speaking Up for Housing Policy Change]

While I was trying to talk to the CFO here, I [thought], “You know what could help? If I had Dignity’s CFO talk to this CFO.” Being able to pair them together, in order to say, “Yeah, we’ve been doing this for 20 years! Where have you been?!” really made it [so] you aren’t carrying that burden alone.

Two, really researching the partner that you’re selecting. Call the state, call the municipalities where they have been to get a sense [of] not just of their finished project, but of their process. How were they to deal with? Did they get their permits in on time? Were there any issues that the city had to cite them for? They may not tell you everything, but sugar on the phone will get you a whole lot. So, really being able to just say, “Listen, we’re looking to explore this for the benefit of the community. Is there anything you can tell me? Anything that worries you about this particular entity?”

Also, see how your cultures fit. The NJCC culture [was] analogous to how I like to work. It can really be a helpful thing if, in fact, you already get along.

Hamdi: My advice would be to look at the financials of the hospital. There’s this assumption on the part of community development and CDFIs that hospitals could actually write a check, and that necessarily is not true. There’s a process of educating and awareness-building that needs to happen within the hospital system, and that takes time. Be prepared to teach, be prepared to learn, but most importantly be patient. And know what you’re walking into. Looking at the 990s, the hospital’s expenditure, and how they invest, and listen to the language that the hospital uses. Those are all indicators of how well the partnership will work.

Also look at how hospitals can invest differently. [Hospitals] can contribute land, investment, and help support a policy that can help strengthen the partnership.

Axel-Lute: NJCC is a statewide organization, they’re relatively large. Would a smaller, more locally based organization have been a potential partner for RWJBarnabas?

Davis: It was really helpful that they were large, and that they were a statewide organization, because we are so large. It would likely be more difficult if they were a regional or municipal-based organization, especially for an investment of this size, right out [of] the gate. I do think, however, that organizations of that size are perfectly situated for other types of hospitals. There are still some stand-alone hospitals. Those that are similarly situated—especially in the same municipality, and they have that same history within a municipality—could very well work together.

Axel-Lute: Has this partnership changed the way each of your organizations works?

Hamdi: Of course. For us, RWJBarnabas has set the standard of how partnerships around health care can be developed. We’ve learned how to approach different hospitals, with expectations in terms of how fast the partnership develops. We have about nine partnerships across the state, but again we keep going back to the partnership with RWJBarnabas Health up in Newark, and now starting in New Brunswick, to demonstrate the evolution of partnerships with health care.

And so, where we have focused on affordable housing alone in Newark, in different communities based on needs assessment we’re focusing on a holistic approach.

It takes time to raise awareness for Hospital A, to literally show restructuring of [an] investment portfolio, what that looks like, and how it is actually practiced. Now it’s a matter of applying it differently as necessitated by the communities.

Davis: It actually helped us trust our own leaders, so that it doesn’t take as long to get an initiative off the ground now. It helped us develop the internal protocols that we go through for our project review, so that now it’s a much smoother process. They were our learning buddies, and we are forever indebted.

Simon: Michellene, in your recent keynote for Root Cause, you talked about the long-term consequences of racism on people, the key steps that an organization has to take to be anti-racist, and implicit racism in health care. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Davis: The four levels of racism are personal, interpersonal, institutional, and structural. “Personal” is private beliefs and prejudices; “interpersonal” [is] the expression of racism between individuals; “institutional” is discriminatory treatment, policies, and practices within organizations; and “structural,” which is what we try to change, [is] systems.

Traditionally I take people back to the 16th century, and talk about everything from the process of colonization, to the codification of the process of colonization in the U.S. Constitution, and how everybody celebrates it. It disenfranchised persons of color; women cannot own property, cannot get an education, etc.

I also talk about the impact and effect of what we saw from the onset of COVID-19. There was an elected official who said, “It’s a great equalizer.” I understood that what he was trying to say was, “Anybody can get it. Anybody can die.” But what we knew was that it was not going to be the great equalizer, it was going to be the great magnifier. It was going to magnify the historical inequities that already currently exist. We’ve really got to help folks understand that it is not that the system is broken; the system works exactly as it was designed. And so, “Congratulations, System. You have really exacerbated and proliferated health inequity, and incredible disparity.” But the one thing that it did was permit us to begin to talk about these things in exactly the right way.

About two years ago, if you said, “structural and systemic racism,” people came for you. Trust me; they came for me. So we always had to say “implicit bias.” We couldn’t just say “your prejudice has shown up before breakfast.” But as a result of [COVID], we’re now able to have the real discussion in real time, to call it what it is, and everybody’s saying “systemic and structural.”

I remember when I first went down to speak to [New Jersey’s] First Lady—when she wanted to start her maternal mortality tour in the state—and I said, “structural and systemic racism,” and her neck popped back. But I said, “I will give you all the data,” and now, I remember being at the launch of Nurture New Jersey, and someone said why did they exist. And [the First Lady] said, “structural and systemic racism.”

Black Lives Matter [has] given us the opportunity to talk about it in real time. Black trauma is so significant. We talk about the long-term negative impact on the physical well-being of individuals as a result of PTSD with veterans. We talk about how chronic stress increases cortisol and can raise blood pressure. And yet we blame the victim when we start talking about [racial] health disparities.

We have a surgeon general who stands up and says that it’s because we have red velvet cake, that we need to eat better at the barbecue. But then you take a look at the Fair Housing Act of 1934, and understand that redlining was done and land wasn’t inhabitable for anybody else, and then zoning laws and other ordinances decided that the incinerator should go right next to that Black community that can’t move out of that area.

A [University of Pennsylvania] study came out in 2018 that literally said the effect of police brutality on Black communities is evidenced in negative mental health days, upwards of three months after a police brutality incident occurs, despite geographic locations. So if it happens in Ferguson, Missouri, I feel it up in Albany. I feel it down in Rice, Texas, thanks to social media. Now, add to that the fact that we don’t get three months.

So I am always weathered under the constant notification that I could die at any moment. And I’m expected to walk into environments, and be on Zooms, and present in meetings, with counterparts who never even blink about it. So then, when we look at health care disparities and the systems that contribute to them, we cannot do that without also acknowledging the fact that there is a highly pressurized environment in which we exist, which evidences itself in the weathering of our physical being. “Weathering” refers to the cell membrane and how it ages us. I’m really 276. Trust me; I feel it right now.

So, the CEO of RWJBarnabas announced to the board that we were going to launch out on an anti-racist journey. There is an anti-racist, systemwide committee being chaired by a member of my team: DeAnna Minus-Vincent. I’m overseeing it, but it has leaders ranging from the chief medical officer to the president of the hospital division. It has subcommittees around HR, because we need to first look at our own selves, figure out how we have contributed to the proliferation of systemic and structural racism through our policies, our practices, our processes.

I keep imploring [people] to commit to an assessment of whether your organization holds a white supremacist culture. There are literal assessments that you can look up. People get upset at the name of it. I don’t care if you call it the “Monday Tuesday List.” Commit to the assessment. Survey your employees, because you need to know where you are at a baseline.

You’ve got to ask, “Who holds the seat of power? Who sets the budget? Who determines the portfolios? Whose voice gets to be in that room, around that table?” If everyone in that room is totally monolithic, then you know that that room is not yet full.

Thank you.

|

|

Comments