This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Dr. Sam Ross, HAN member, Bon Secours Mercy Health’s chief community health officer, speaking at the Housing for Health Policy Day 2020 Congressional briefing.

Over the past decade, the health care sector has grappled with a central question: What should its role be in addressing the social determinants of health (SDOH)? Decades of accumulated research have shown that social and physical environments and economic factors—the opportunities and barriers facing individuals and families in their daily lives—play a larger role than medical care in shaping health outcomes.

As they acquire this knowledge, health care leaders have considered a range of possible courses to take. One obvious goal is to ensure that patients’ social and economic challenges do not prevent them from receiving high quality health care, by developing a conscious practice of “social risk-informed” care, or health care that takes into account patients’ social and economic barriers to health. Health care organizations are also increasingly implementing programs to identify patients’ social needs and refer them to relevant services. Health care organizations are co-locating nonmedical resources such as food, legal support, and financial services at health sites to increase access to these programs.

A growing number of hospitals and health systems, including members of Healthcare Anchor Network (HAN), are also using their economic resources, which in some cases are considerable, and devoting a small portion of their investment portfolio to accelerate, expand, and focus on affordable housing, healthy food financing, child development, and small business development in communities where health inequities are concentrated. They are also engaged in inclusive local hiring and sourcing from local minority- and women-owned businesses to strengthen neighborhood economic ecosystems.

These efforts are helpful, but insufficient on their own given the scope and scale of the economic and social inequalities in communities across the nation. Our country’s investment in social support is inadequate, and many communities are increasingly overwhelmed by the effects of growing socioeconomic inequities. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on disadvantaged communities of color, particularly African Americans, has spotlighted these clear health, racial, and economic inequalities.

The toxic stress associated with food and housing insecurity, a lack of a livable wage, and limited access to primary care has produced a flood of people in emergency rooms with preventable chronic conditions as well as behavioral health and substance abuse problems. Six in 10 adults in the U.S. have a chronic disease, such as heart disease or diabetes, and 4 in 10 have two or more. Their health cannot be substantially improved without addressing their associated social and economic needs. Health care professionals and leaders are coming to grips with the fact that to build health and well-being in communities, systematic change is needed.

Hospital engagement in the public policy arena has historically focused on advocacy to increase reimbursement for medical services, which is significantly driven by a fee-for-service system that rewards conducting procedures and filling beds. While health care leaders may have personal interests in social welfare, their core responsibility has been to sustain and grow their medical-focused businesses.

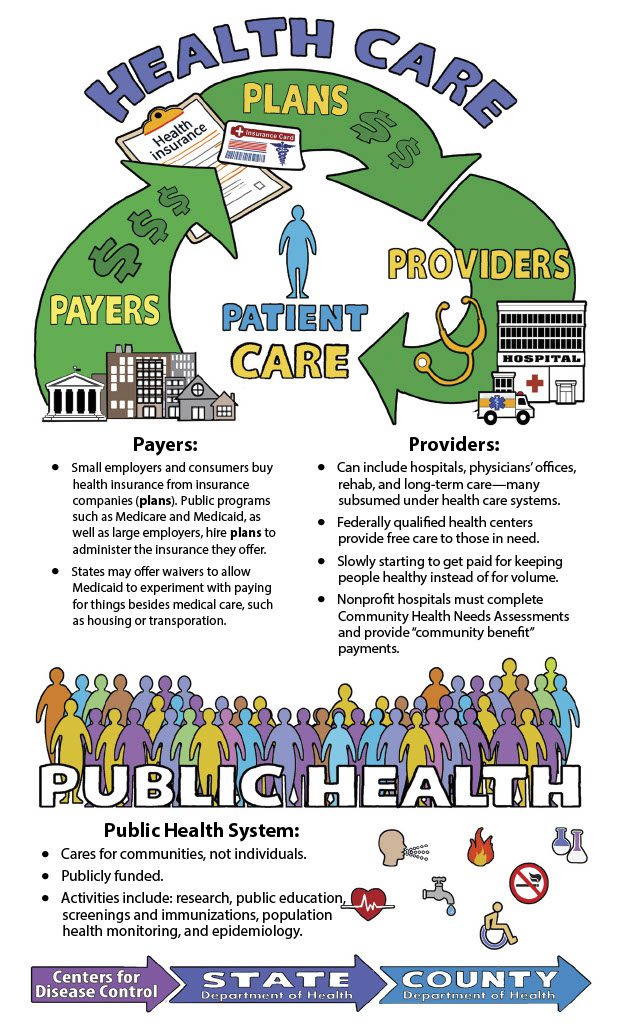

Value-based care is changing that dynamic. Under value-based care, providers and hospitals are paid based on the quality and efficiency of care provided, not on the number of services. Although efforts to rein in U.S. health care costs and improve outcomes predated the Affordable Care Act, the landmark health care legislation greatly accelerated the value-based care transformation by instituting a number of new federal programs that reimbursed providers based on outcomes, and in some cases penalized them for failing to meet certain benchmarks.

The health care sector is taking on increasing financial risk to keep people healthy and out of their emergency rooms because health care’s bottom line is increasingly dependent on the availability of affordable housing, livable wages, safe neighborhoods, affordable healthy food, high quality K-12 schools, affordable child care, and built environments that support healthy behaviors, all policy areas that have traditionally been outside the scope of health care organization policy advocacy. Civic engagement around social policy is therefore gradually coming into focus for the health care sector as a helpful, and in some cases, essential strategy to amplify its own programmatic efforts on social determinants and to enable it to succeed under value-based care.

The Healthcare Anchor Network (HAN) is a group of health care systems that have joined together to learn from each other how to be effective “anchor institutions,” or how to use their local economic power, human capital, and political resources to improve local economies and reduce local economic inequities as a way to improve health and health equity in the communities they serve.

HAN was founded in late 2017 after leaders from 40 health systems convened to explore how their institutions could more fully harness their economic power to inclusively and sustainably benefit the long-term well-being of communities. Soon after the conclusion of the convening, HAN was formed to make it easier for health systems to collaborate nationally, in order to accelerate learning and local implementation of these economic inclusion strategies. HAN is convened by the nonprofit The Democracy Collaborative, and now includes 50 health systems, representing 700 hospitals.

The central strategies used by Healthcare Anchor Network members have focused principally on hiring, procurement, and investments. In the past two years however, the network has added policy and advocacy to its portfolio, recognizing that health system efforts can only go so far, and that substantial improvements in economic equity will only be possible through changes in governmental funding priorities and policies. The need for HAN to engage in policy advocacy had been raised at all of the HAN convenings, but at the spring 2018 convening, HAN members decided that it was time to move forward and formed the HAN Aligning to Advance Policy Initiative Group. There was no dissent on this decision but, as is often the case with coalitions, those most supportive became the most active group members while others needed to be briefed on the issues and engaged to support the goals and activities of the group.

In partnership with Enterprise Community Partners, a national affordable housing nonprofit, HAN has held two federal Housing for Health Policy Days in the past two years in Washington, D.C., to highlight the links between housing and health and to advocate for increases in federal funding for affordable, healthy housing.

Eighteen network members participated in Policy Day 2020, including the policy briefing. They urged their members of Congress and key Congressional housing committee members to support and advance two priority policy proposals, enacting the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act of 2019 and increasing funding for the HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) by at least $1.5 billion. These asks were selected by HAN after researching the various federal affordable housing programs and creating vetting criteria that included considerations such as how significant an impact a given program has, whether it helps a broad range of disadvantaged individuals, and whether the health care voice can help to push the issue to success.

Both congressional members and their staff expressed appreciation, and in some cases surprise, at seeing health systems advocate about housing issues. Several lauded health system leaders for speaking and taking action on an issue that at face value is not related to those health systems’ direct financial interests. The early impacts have ranged from HAN members getting key members of Congress from both parties to attend and speak at the Policy Days, and obtaining bipartisan support from senators and representatives to co-sponsor the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act and sign onto the HOME appropriation letter.

These HAN health systems aim to create health sector-level change by collectively advocating for SDOH policies. However, it is not an easy and simple shift for these health care institutions. Government relations staffers, leadership, and other key staff at the institutions need to know why this is a needed priority to take on—in addition to their healthcare advocacy work.

One question raised by a health care institution at the first in-person policy strategy session was: Why should health systems use their political capital for programs like affordable housing that will not directly support needed hospital services? Another concern focused on whether health care funding would be pitted against SDOH funding and, if so, whether it would make sense to devote organizational resources to advocating for housing funding.

There are multiple benefits for health organizations that engage in SDOH policy advocacy activities. In addition to helping health organizations thrive financially under value-based care, SDOH policy work provides an opportunity to partner and build trust with community groups and, if advocacy is successful, to scale SDOH investments and build community capacity and resilience. While policy advocacy by health care organizations to address social determinants may be unexpected, recent HAN members’ experience suggests it builds good will with local, state, and federal decision makers. At a time of increasing demands for transparency and public scrutiny of the health care sector, taking action that has a clear purpose to contribute to the common good is both smart and in the long-term strategic interest of the health care sector. Policy advocacy can also provide a way for health care organizations in the same community, who might otherwise be competing for patients, to work together.

Health organizations seeking to engage in SDOH policy advocacy and civic engagement have a multitude of policy issues, activities, and levels of government to choose from. Policy advocacy activities are also relatively low-cost strategies that can yield substantial benefits. A government relations or community health staff person can play an important role in helping local, state, or national advocacy organizations determine which advocacy activities to support. They can then serve as internal resources for senior leaders, both in framing issues and identifying options for advocacy. With this targeted information, key senior leaders can make efficient use of their time to write letters, make calls to key leaders, and in some cases, authorize broader actions that demonstrate organizational commitment and build political momentum. Once implemented, policy changes that have been effectively designed will yield long-term widespread benefits.

Senior leaders of health care organizations have significant potential to influence both public policy and public opinion. They are held in high regard on a range of issues, and putting a stake in the ground on issues of equity adds a prominent voice to the public policy discussion.

At the national level, both the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States played important roles in advocating for passage of the Affordable Care Act. It should be noted that other major health care stakeholder groups such as the American Medical Association have exerted their influence against health reform at the national level. And at the local level, it is important to note that hospitals are among the largest employers in both urban and rural communities and failure to mobilize their associated political influence on issues that clearly impact health represents a significant missed opportunity. Local examples in recent years include advocacy in partnership with community stakeholders by Cone Health in Greensboro, North Carolina, to ensure municipal enforcement of healthy housing ordinances in multi-unit apartment complexes, and advocacy by UMass Memorial Health System in partnership with community stakeholders in Worcester, Massachusetts, to prohibit tobacco sales in local pharmacies.

Although health care professionals and organizations are not viewed as experts in social policy issues, their advocacy around these issues may be particularly influential specifically because it represents additional (and powerful) support from an unexpected source. When respected health leaders speak out about social policy issues, it helps reframe issues that are often politically polarized—into more palatable health issues. An example of this is the debate around paid leave. If viewed solely as an economic issue, paid leave legislation can become mired in debates about government interference in the economy. When viewed in terms of its health implications, these policy debates become about more than economic policy, they are about enabling breadwinners to recover from illnesses and to care for loved ones, and to prevent transmission of illnesses in the workplace. In this way, having health professionals and leaders speak about social policy issues can help reframe debates and depoliticize certain issues.

Civic engagement and policy advocacy on SDOH issues do not come without risks. Leaders may be reluctant to advocate for issues if their organizations have not provided leadership themselves in a given area, for fear of generating public demands for action beyond what they may believe to be their capacity. Many are also reluctant to step into unfamiliar issues, potentially exposing themselves to ridicule if they take positions viewed as uninformed. Still others are concerned about being viewed as venturing into issues where they do not have the authority to lead. In one instance, a HAN member government relations person commented that he still did not feel fully comfortable with lobbying on specific housing legislation and programs despite participating in HAN’s housing and health webinar.

Many of these concerns can be addressed through partnerships with community-based organizations and advocacy groups. In fact, it is crucial that any health system social policy and civic engagement efforts be coordinated and aligned with the needs of the intended beneficiaries to avoid the unintended consequences that often occur when well-meaning individuals seek solutions without consulting those most affected. For example, community health-needs assessments can be used to identify not just the most prevalent and urgent health priorities but also the social and economic issues that drive those issues. For example, HAN members Rush University Medical Center, AMITA Health, and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago are founding members of West Side United, a community coalition working to make their neighborhoods stronger, healthier, and more vibrant places to live. West Side United’s community engagement continuum incorporates five phases for building a community engagement strategy that is grounded in relationships built on trust, communication, and mutual respect. One area of focus is the investment of capital and resources in community infrastructure, including affordable housing.

After identifying key community priorities through community engagement, health care organizations can reach out to subject-matter experts in advocacy organizations to understand current policy debates and identify opportunities for engagement that match organizations’ priorities and capacity. For example, with HAN’s affordable housing advocacy work, Enterprise staff provided trainings and ongoing advocacy information to HAN members. Thanks to this, the HAN member who had some hesitancy with the federal housing policy priorities has built up his housing knowledge so that the health system he represents signed up for Capitol Hill visits on HAN Policy Day 2020 to speak to members of Congress.

Some health care organizations may feel that SDOH policy advocacy falls too far outside their scope or is not an important enough priority. Those who seek to thrive in a financing system that incentivizes keeping people healthy and out of acute-care settings see that stronger SDOH civic engagement and policy advocacy is not only helpful but essential. While stepping into the SDOH arena, hospitals recognize the continuing imperative to provide the highest quality clinical services. As organizations already enmeshed in a process of transformation in the financing and delivery of clinical services, they have a critical choice to make. Either they accept an inevitable contraction of their enterprise to the provision of acute care services as contractors, or they embrace an emerging identity as community health improvement systems. The latter choice clearly requires the development of intersectoral partnerships with diverse stakeholders as well as policy advocacy for increased investment in both the public and private sector to help address the SDOH. As community and economic development groups engage these institutions, it is important to understand the many fundamental challenges these complex organizations face at all levels in pivoting from a financing system that incentivizes the delivery of clinical services to one that rewards efforts to keep people healthy and out of their facilities. It will be important to offer entry points for engagement that build knowledge and understanding and represent important incremental steps toward a realized ideal. For example, there is growing attention to co-investment by hospitals and health plans in medical respite facilities for homeless populations as a step in building a continuum that includes permanent supportive housing. These respite facilities provide care, support, counseling, and enrollment in programs to prepare homeless people for entry into more stable settings, and represent a much more cost-effective alternative to “warehousing” in acute care settings, or worse, discharge back into the streets.

One of the revelations of the 21st century is that siloed specialization is an inadequate and inefficient means of solving complex problems. Health care transformation at its core is about how health care organizations share ownership with other sectors to improve health and well-being in our communities. Building the internal capacity for SDOH policy advocacy and civic engagement is becoming an essential part of the future for health care organizations.

|

|

Growing socioeconomic inequities are a result of economic public policies, not social policies, at all levels of govt. My city of San Antonio, Tx is a case study in this regard: we are now the poorest urban city in the U.S. Why? Because of our long-range “vision”,one based upon the universal “urban planning” model, which focuses upon the built environment, where civic success is measured in business development terms, not in socioeconomic terms. Health care is an industry, just like the commercial real estate industry, all of whom rely upon a sophisticated business model of business income accumulation.

I do not see this challenge as a policy advocacy, community engagement, delivery of clinical services, “economic development” organizations (who focus on business development), or in intersectoral partnerships, I see it as a need to replace adopted long-term “visions” which incentivizes the built environment, utilizing heavy public subsidies. There is a great need to measure for impacts & outcomes using this old, narrow, limited yardstick of “success” to see their community deficiencies. Health care systems need to team up with CED practitioners who reject this old model, so that instead of responding & reacting to harmful health outputs, the idea is to participate on the front-end of the economic policymaking “vision”, to thus produce greater health impacts & outcomes.

We must do more than see health care improvement, we must become instrumental in moving the needle in structural terms, not just in terms of better programs, services, or productivity. The urban planning model remains untouched & unexamined for its detrimental socioeconomic & health effects upon communities across the U.S.