Photo by Nakashi via Flickr, CC-BY-SA-2.0

The tragic murder of George Floyd and the subsequent nationwide protests have prompted a long needed and delayed discussion of inequality and economic injustice. The discussion of reparations for African Americans has been elevated, including key contributions by my colleague Dedrick Asante-Muhammed. Part of the solution toward tackling persistent inequality would be the expansion of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) broadly throughout the financial industry.

Most commentators focus on income inequality. While important, the economic stagnation in this country will not be addressed unless we tackle glaring and deepening wealth inequality. Individual and community wealth supports decent education, housing, and life chances for people. If society has systematically discriminated against racial and ethnic groups, then those groups will face daunting handicaps in their efforts to provide for their families and climb economically. Their towns and jurisdictions will not have the resources via property taxes and other taxes to support decent education and other community infrastructure. The losers are not only the victims of discrimination but ultimately all of us as inequality impedes economic growth and increases political and social polarization.

While many agents (public and private sector) have practiced invidious discrimination, the financial industry has been one of the main perpetrators of discrimination and disparate treatment over the decades. An antidote to banking discrimination is a law that says the financial industry has an affirmative obligation to serve all communities, but particularly communities of color and low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities. The present day CRA as applied to banks is an income-based law but a future CRA must be expanded to include race.

Background of Disparities and Discrimination

First, a few statistics about wealth inequality. The Urban Institute calculates that families near the top of the wealth distribution had six times the wealth of those in the middle of the distribution in 1963 but now have twelve times the wealth. Viewed through a racial lens, the average white family had seven times the wealth of an African American family and five times the wealth of a Hispanic family by 2016, a disparity that has persisted since 1963. The disparity also grows with the age of the householder. According to the Urban Institute, “In their 30s, whites have an average of $147,000 more in wealth than Blacks (three times as much). By their 60s, whites have over $1.1 million more in average wealth than Blacks (seven times as much).”

Photo in public domain

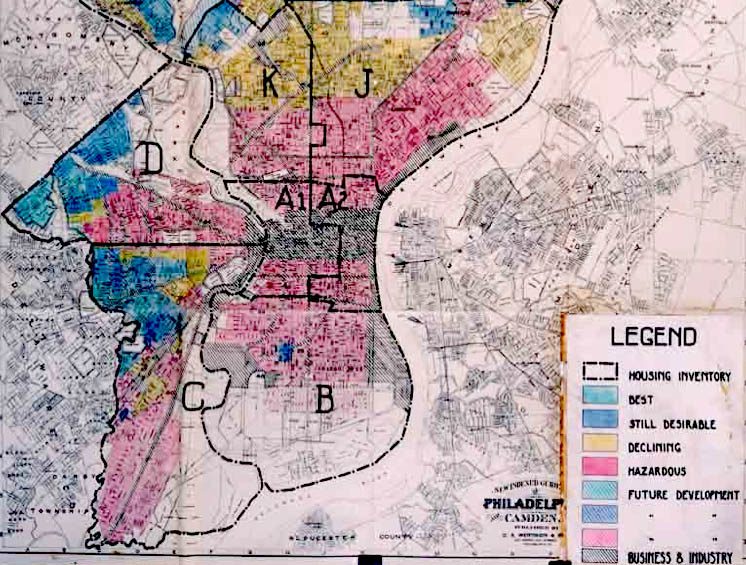

The causes of these disparities are complex and several but discrimination in the financial marketplace and the housing markets is a significant contributor. Previous NCRC research has documented government-sponsored redlining that the financial sector readily adopted. In the 1930s, the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) developed maps, in consultation with local appraisers, bank officers, and government officials, describing the housing conditions and lending possibilities in neighborhoods in cities across America. Neighborhoods with higher percentages of minorities were described as higher-risk. These maps discouraged lending institutions from making loans in communities of color. In later decades, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) prohibited developers and lenders from arranging for and offering people of color FHA-backed loans in the newly developing segregated suburban communities. Meanwhile, center city neighborhoods populated by people of color remained redlined. This discrimination resulted in few loans being made for African Americans and other minorities in rapidly growing suburban communities and even fewer loans for people of color in segregated urban communities across the postwar decades.

Communities of color remained credit-starved in the 1990s and 2000s, leaving them susceptible to high-cost subprime and predatory lending that extracted what little wealth they were able to accumulate. NCRC and other researchers found that after controlling for creditworthiness and other underwriting variables, African Americans were still more likely than whites to receive high-cost loans, as defined in the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) data, which disproportionately resulted in foreclosure. In a study examining the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, NCRC controlled for borrower characteristics, loan terms, and housing conditions and found that in the mid-2000s, Latinos were 70 percent more likely and African Americans 80 percent more likely than their white counterparts to receive a subprime loan. In addition, African Americans were almost 20 percent more likely and Latinos were 90 percent more likely than their similarly situated white counterparts to go into foreclosure.

This unequal treatment is not confined to just banking. Redlining in the insurance industry continues to be researched. Greg Squires conducted a number of studies in the 1990s documenting racial disparities in access to homeowners’ insurance. In addition, Squires reported that “the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (an organization of state insurance commissioners who regulate the insurance industry) concluded in an analysis of 33 cities in 20 states that there is considerable evidence that residents of urban communities, particularly low-income and minority neighborhoods, face greater difficulty in obtaining high-quality homeowners insurance coverage through the voluntary market, when compared to residents of other areas.”

More recently, ProPublica and Consumer Reports found that the disparities in premiums between African American and white neighborhoods for automobile insurance in California, Illinois, Texas, and Missouri were higher than can be explained by differences in risk. Persistent differences in access and prices for financial products significantly reduce wealth accumulation by people and communities of color.

While I am not aware of research probing for discrimination in the securities markets, racial and income disparities are nevertheless stark. The Pew Research Center found that a slight majority of Americans have some stock holdings, mostly through 401(k)s and other retirement savings, but the amount invested in stock varies widely by income (a median investment of $8,400 for those with incomes under $35,000 compared to $138,700 for those with incomes of $100,000 and higher). Moreover, about 61 percent of white households own stock compared to about 30 percent for Hispanics and African Americans.

The insights of Thomas Piketty suggest that these inequalities in stock ownership will exacerbate wealth inequality over the decades and generations. The average rate of return of 7 percent to 8 percent in stock market investments grows exponentially through the years, meaning that those who have stock will reap tens or hundreds of thousands in wealth accumulation while those without stock see no wealth accumulation. Add this disparity in stocks to the extreme racial disparities in homeownership caused in no small part due to redlining (over 70 percent homeownership for whites versus under 45 percent for African Americans), and it is no surprise that this country is an unequal society with growing distress and economic stasis.

In “The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap,” Mehrsa Baradaran’s theme was that African American banks had trouble growing because a discriminatory and segregated society resulted in communities of color with low levels of savings and wealth that could not support minority-owned financial institutions. Applying this theme to the financial industry writ large would amount to this assertion: If modest-income communities and communities of color remain outside of the financial mainstream, they face daunting challenges in revitalizing themselves and achieving anything close to economic parity with predominantly white neighborhoods. The financial industry is a mechanism for accumulating and investing society’s assets and wealth. When some communities are excluded from the financial industry, they are excluded from a fair share of society’s resources. Grinding inequalities and poverty will result. Combating this is a powerful rationale for applying CRA broadly throughout the financial industry.

Quid Pro Quo–We Insure You, You Must Reinvest

In addition to combating redlining, a statutory rationale for CRA was that in return for federal deposit insurance, banks must reinvest their deposits into communities. For many years, discussions about applying CRA to other parts of the financial industry stalled since federal guarantees and subsidies did not seem as visible for other parts of the industry. However, this perspective changed dramatically during the 2008 financial crisis. Financial institutions’ abusive lending was a major cause of the crisis; then, the government had to bail out the culprits. A dramatic illustration that non-banks would be rescued by the federal government occurred when Bear Stearns was the first non-bank to access credit via the Federal Reserve Discount window during the crisis.

Eugene Ludwig, a former Comptroller of the Currency, recently stated, “If you’re supported by the federal government, economically—and everybody is to some degree or another, and that is particularly obvious right now—then in particular, you have a broader set of responsibilities, it seems to me. To perhaps put a finer point on this, where the [Federal Reserve] is using its tools to support a business, or an investor in a business, it is using the government safety net, and this should particularly convey upon the recipients additional societal obligations.”

Before the financial crisis, Congress had already significantly blurred the lines between banks and non-banks with the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999. This law allowed banks to own non-banks including insurance companies and securities firms. Since banks can now own non-banks, shouldn’t CRA expand throughout these conglomerates?

Subsequently, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 created the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), which is an interagency council whose role is to safeguard the stability of the financial industry. The FSOC oversees systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs), both banks and non-banks. SIFIs are so large that their failure would imperil the entire financial industry. They are subject to enhanced regulation, capital reserve requirements, and stress testing to help ensure they can weather recessions. Given the government’s oversight and safeguarding of these institutions, shouldn’t they have reinvestment requirements?

A financial institution is distinct from other companies in that a financial institution invests and safeguards individual and community wealth. When financial companies’ ability to use people’s wealth is unchecked, socially undesirable consequences such as monopolization and manipulation result, as argued by former Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis. “But even more profitable is the privilege of taking the golden eggs laid by somebody else’s goose. The investment bankers and their associates now enjoy that privilege. They control the people through the people’s own money. If the bankers’ power were commensurate only with their wealth, they would have relatively little influence on American business,” he said.

In contrast, under strong regulatory oversight, a community reinvestment obligation and public accountability, financial institutions are more likely to use other people’s money in a socially optimal manner. Financial companies would reinvest community wealth in affordable housing and community development, which benefits society as a whole. Financial institutions benefit from other people’s money in a number of different forms: deposits for banks, investments in stocks and bonds for securities firms and broker-dealers, and premium payments for insurance companies. Hence, a quid pro quo for receiving other people’s money is a community reinvestment obligation.

The Size of the Financial Industry: Marshaling Resources for Community Reinvestment

Photo by Javier via Flickr. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

If community reinvestment obligations remain confined to banks, CRA will cover a shrinking segment of the financial industry and its success in revitalizing communities will be diminished. Speaking in the late 1990s, former Comptroller Ludwig stated, “At the end of 1996, for the first time, the dollar volume of mutual funds exceeded the dollar volume of bank deposits.” By 2017, global non-bank assets totaled $52 trillion, up dramatically from $30 trillion in 2010.

Here are some other facts about the massive amount of resources in non-banks:

- Insurance companies collected $1.2 trillion in premiums in 2018, with property and casualty insurance accounting for about half of this amount.

- The U.S. mutual fund industry has $21 trillion in total assets.

- Independent mortgage companies have out-competed banks in recent years, making more than half of all home loans, according to NCRC research.

CRA cannot remain a sole obligation of banks. It will be undermined if it remains so confined. Banks will increasingly face a competitive disadvantage, as other firms are free to seek the most profits by predominantly serving only the affluent. By spreading reinvestment obligations across the financial industry, the competitive playing field is leveled and all communities benefit from the accumulated wealth of the country.

How Would CRA be Applied across the Financial Industry

Examinations are not as difficult to imagine for non-banks as some may think. Many non-bank activities such as making loans or offering insurance products are amenable to data collection and analysis, including assessing the percentage of low- and moderate-income customers and communities served. In addition, a community development test would evaluate the types and levels of affordable housing and economic development loans and investments.

Cohen and Agresti further explain how to envision tests for non-banks including securities firms:

“Including investment banks and broker-dealers in the CRA should not be seen as a burden. Rather, these institutions could comply with the act in ways that continue to focus on their core competencies, while simultaneously increasing access to financial expertise and capital for low-income, minority, and underserved communities.

Investment banks could create funds for and provide direct investment in businesses owned by low-income individuals and minorities or businesses located in low-income and minority communities. Broker-dealers could sell shares in these funds or the actual debt and equity securities issued. Investment banks and broker dealers could provide training and technical assistance for individuals, entrepreneurs and small businesses. They could locate facilities in underserved areas, or provide sponsorship for charter schools for underserved populations.”

A real life example of how to apply CRA to non-banks is the state of Massachusetts, which has conducted CRA exams of mortgage companies and credit unions for several years. The Massachusetts model can be readily adapted on a federal level.

Applying CRA broadly throughout the financial industry is not merely an appealing policy initiative. It is imperative. Sen. William Proxmire, the father of CRA, stated that during the debates leading to CRA’s passage, the federal government did not have the resources by itself to revitalize distressed communities. This is truer today. The financial sector is the guardian of the lion’s share of society’s collective wealth. For community wealth to benefit all communities, including those that have been traditionally excluded, CRA must direct the financial industry to provide capital and credit to where it is due.

This piece was originally published by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

Comments