James Knauss started his own landscaping company called Transformalawn. Knauss, who was formerly incarcerated, was able to get a business loan from Hope Enterprise Corporation.

Brenda Davis started a dog grooming business in Colorado Springs called Clip-n-dales.

In 2017, Brenda Davis was finally free. She’d been convicted of financial crimes and given a 10-year sentence, and after five years in prison, she was out on parole. But whatever excitement she’d had about the new life ahead of her was quickly tempered by the brutal realities encountered by just about everyone who’s been incarcerated.

“You can’t hardly find a place to live with a criminal record, can’t hardly rent a space to do anything in. It’s awful,” she says. “I went out to find a regular job, and the only places that’ll hire me is McDonald’s or Burger King—even Taco Bell won’t hire full time.”

Many people who’ve recently been released from jail or prison struggle to get their lives going, and availability of money is key to that effort. Some have debts that must be cleared up before they can move forward; others need money to put down a deposit on a place to live in order to achieve some independence. And in some cases, the prospect of starting their own business seems likelier than landing a full-time job with promise. But after years behind bars, many returning citizens have few people to rely on and little or no credit history—which means that pulling together even a small sum can be almost impossible.

“People come out with nothing: no social network anymore, depending how long they’ve been in prison; no place to live; no job. And their family might not have much either. It’s a huge burden,” says Donna Fabiani, executive vice president for knowledge sharing at the Opportunity Finance Network, a national association of community development financial institutions (CDFIs).

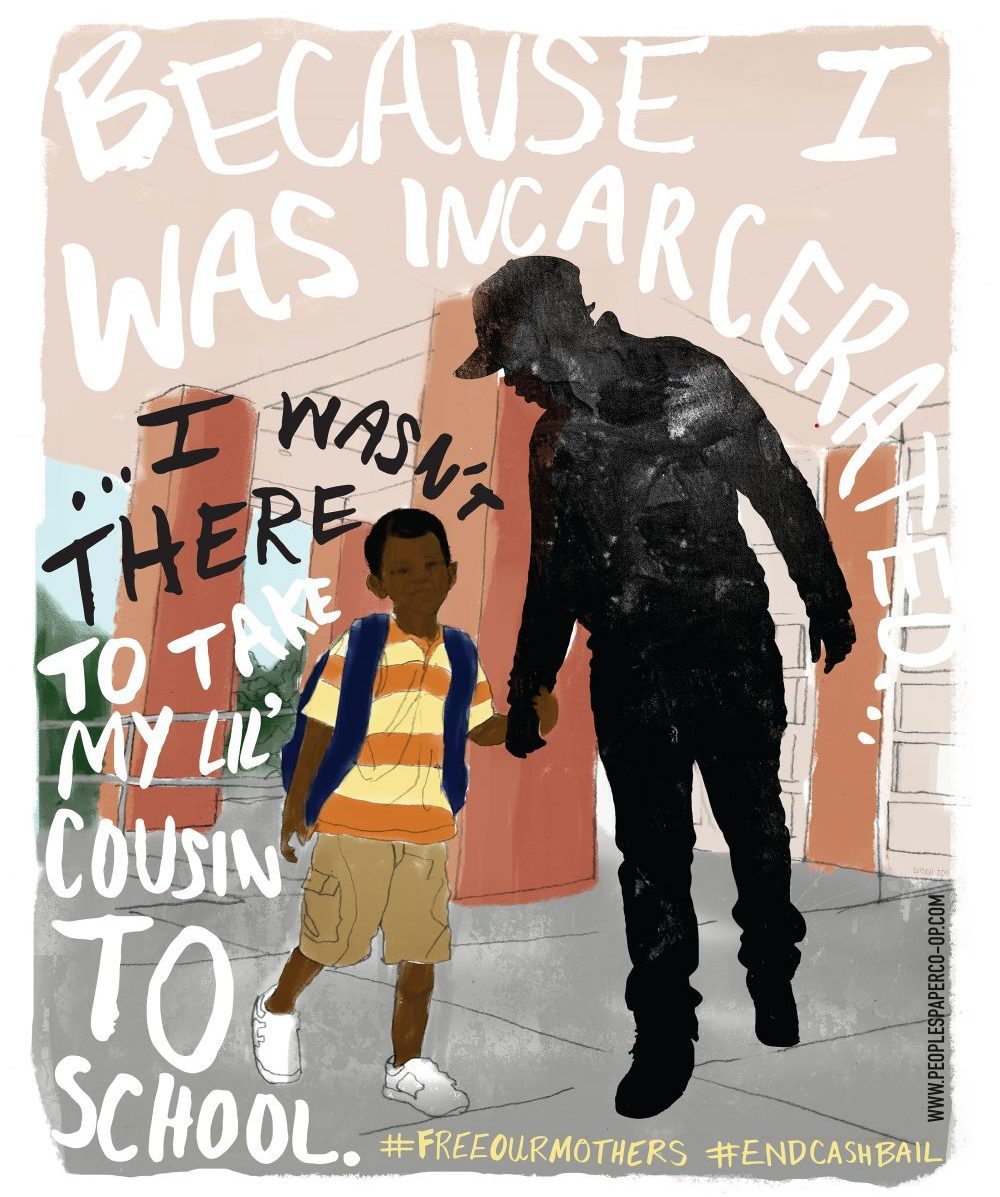

The need is enormous. Currently, over 70 million Americans—nearly one out of three adults of working age—have a criminal record. And many of those affected were already poor and marginalized before their conviction: one report estimates that 80 percent of those currently incarcerated are low income and that 40 percent of all crimes are estimated to be linked to poverty.

Having a criminal record does not, in itself, bar anyone from obtaining a business loan. But many people leave prison with huge debts, often in the tens of thousands of dollars, from conviction-related costs, missed payments, prison charges, or child support. And some of those debts, particularly if they’re delinquent, can show up on a credit report. People who’ve spent years in detention are also common targets of scams and identity theft. All of those things can affect their ability to gain access to capital. After all, having “good credit” means being able to demonstrate a history of responsibly managing financial products over time.

CDFIs have always focused their efforts on underserved communities. Until recently, though, formerly incarcerated people didn’t receive much attention. But as the U.S. justice system and its failings have grown in the national consciousness over the past few years, community lenders and other nonprofit organizations have begun to tailor programs for justice system–involved individuals, creating specific loan products, credit scoring systems, and even business courses that can smooth the path back to productive life.

Davis is one of the people who found her way into the business world in order to make a living. Today, she’s is an entrepreneur in Colorado Springs with a dog grooming business, Clip-n-dales, that’s just about to go live. That success is the result not only of her tenacity and hard work, but also of a couple of visionary programs that helped her prepare and enter the business realm. “If it wasn’t for [those programs], I wouldn’t know any of the stuff I needed to know,” says Davis.

Meeting People Where They Are

An increasing number of CDFIs are interested in tailoring their services to people with criminal records, but so far, only a handful of organizations are actually doing it in an intentional manner. Hope Enterprise Corporation is one of them. A CDFI with branches in Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee—states with some of the highest incarceration rates in the country—Hope sees the work as crucial to its mission.

Sharon Strahan gets credit counseling from Hope Enterprise Corporation. Photo courtesy of HOPE Enterprise Corporation

“Incarceration can knock people into poverty for a long time,” says Diane Standaert, Hope’s senior vice president of policy and advocacy. Even pre-trial detention, without a guilty conviction, can lead to damaged credit scores, lost jobs or houses, and an accumulation of fines and fees. “Given our history, this is central to our work. It’s critical to help people have a pathway” back into mainstream society, she adds.

Hope is deeply embedded in the communities in which it works; for years, it has been taking referrals from social service organizations that know of individuals in need of small loans to help them get on their feet. In some regions, staff also make presentations within prisons and jails to introduce Hope’s services before people are released.

Laying that kind of foundation is useful, because many returning citizens are deeply mistrustful of banks and other financial institutions. In part, says Cassandra Williams, a Hope regional branch administrator based in Memphis, that’s because predatory services have been so readily available in African American and low-income communities.” Additionally, if ex-offenders owe back child support or have other institutional debts, their wages can be garnished if deposited into a bank account. And there may also simply be a general mistrust of “the system” on the part of people who’ve lived outside of it for some time.

So building a sense of trust and offering a welcoming environment is key. “It’s about meeting the person where they are,” explains Williams. If a returning citizen has no credit background or one that’s long gone stale, Hope will examine their experience with paying rent or cell phone bills. And some low-dollar loans require very little history at all. With Hope’s Borrow and Save loan, for example, half of the loan goes into a savings account, while the other half goes to the individual. Once they’ve paid off the loan, the other half is available to them, with interest. Another product lets clients borrow against their own savings accounts.

Those small loans help the borrowers begin to establish credit, says Williams. Eventually, some returning citizens move on to buy cars and even homes. Others start their own enterprises. Williams remembers one man who was released from jail in 2014 and wound up in a homeless shelter in Memphis. At some point, he found his way to Hope and its products. “By June 2017, he got a loan through Hope to purchase equipment he needed to launch his business,” she says, which was a landscaping company called Transformalawn.

In Ithaca, New York, Alternatives Federal Credit Union is aiming to do similar work. Within the next few weeks, the CDFI plans to start issuing what Chief Lending Officer Carol Chernikoff described as “micro, micro, get-back-on-your-feet loans” that can help people recently released from prison pay for door-opening costs like court fines, transportation, work clothes, or textbooks.

Alternatives tackled the challenge by first spending months listening to groups that work with formerly incarcerated people, as well as to returning citizens themselves. “We don’t believe we know what’s best. We don’t want to tell people what they need,” says Chernikoff.

The credit union has since partnered with local organizations that provide direct services to people re-entering society; they will recommend clients to Alternatives.

The goal is to get prospective borrowers into the credit union and offer them small loans, $500 or less. Those will be borrowed against a fund Alternatives established specifically for this program, making it less of an emergency for both the credit union and the borrower if the loan isn’t repaid. Borrowers won’t need a credit history to access these loans.

Like Hope, Alternatives sees much of their efforts being focused on relationship-building. “Once we have a history with people, we’re much more open to working with them—working from that history and not a credit report,” says Chernikoff, referring to other Alternatives programs and loans that can help borrowers establish credit and progress toward their financial goals. “And if someone is clearly taking positive steps and taking the advice of our financial counselors, that adds to everything.”

Circumventing Barriers

Working with marginalized groups always has its challenges. In this case, one stumbling block is that the major credit reporting agencies only accept lenders with at least 100 active loans in their portfolio. So small organizations and CDFIs that don’t meet that volume threshold can’t benefit their borrowers by reporting the loan information to the credit bureaus. That means borrowers might be obtaining loans, but they’re not building their credit in order to eventually transition to mainstream financial systems.

The Credit Builders Alliance (CBA), a nonprofit in Washington, D.C., was established in 2008 by a handful of nonprofit lenders. The organization offers technical assistance to small lending institutions and has created several toolkits that highlight challenges and best practices in providing loans to returning citizens.

Above all, though, it helps its members get past the credit reporting barrier. On a monthly basis, CBA bundles together the loans of over 100 small lenders so that they can surpass the agencies’ threshold and report the loans. That allows the lenders to do their hands-on work—“looking at a holistic picture of a borrower’s need, not just a credit score that’s a standard way of vetting,” says Sarah Chenven, chief operating and strategy officer at Credit Builders Alliance—while still reaping the benefits of the traditional credit system.

Teresa Hodge and her daughter Laurin Leonard have found another highly innovative way to deal with the credit challenges facing ex-offenders. Formerly incarcerated herself, Hodge later founded a nonprofit to help individuals with criminal records move into entrepreneurship. She observed, however, that background checks and access to credit were huge obstacles.

Enter the R3 score. Created by Hodge and Leonard using a proprietary formula, the score starts with an intake application of around 150 questions asking a potential applicant about his or her employment and education history. The data then goes into an algorithm that comes up with an alternative credit score.

The goal, says Leonard, is to “understand who a person was prior to entering the justice system.” And it allows an applicant to provide context and mitigating circumstances regarding their incarceration that wouldn’t accompany a standard check, which is just a database query.

The R3 score has already attracted notice among CDFIs; Hodge was a featured speaker at the Opportunity Finance Network conference this year. “CDFIs have the capital, but don’t have the process to assess candidates,” says Leonard. With the R3 score, she says, community development lenders can utilize that capital to support entrepreneurs with records.

But the score has also found adherents in the property management and human resources worlds, where managers might be philosophically OK with hiring someone with a criminal record, but have no way to determine the risk of a particular candidate. “We’re finding that a contextualized background check has widespread use, though we started out just trying to help with loans,” says Leonard.

Entrepreneurship as a Way Up and Out

Organizations that help returning citizens regain their footing in society often start out with a focus on housing and jobs and consumer loans. Over time, though, it’s not uncommon for them to shift to a concentration on entrepreneurship and business skills.

That’s what happened with The First 72+, an organization in New Orleans that focuses on helping formerly incarcerated individuals get on their feet and thrive. The group began by providing wraparound services, but launched a business incubator because the need was so obvious. There are so many barriers to traditional employment for ex-offenders that entrepreneurship can be a natural fit.

“They often have a history and experience in entrepreneurship—some in the illicit economy, some in both [illicit and licit], but have very little experience legitimizing their business,” says Kelly Orians, co-director of The First 72+ in New Orleans. (The name references the critical first three days after someone has been released from detention.)

So the organization set up an incubator program that can help clients formalize what may have started out as a side hustle. “Our folks come in at different levels, and we have different tracks,” says Orians. Some people know what they want to do, but don’t yet have the skills, so the organization assists them in resolving outstanding issues and developing their capabilities. Others already are doing something, and The First 72+ helps them begin to think about monitoring cash flow and scaling their business.

For example, says Orians, one man who’d formerly been incarcerated “started doing window tinting; he’d drive around and tint people’s windows. We helped him scale up, find a location, expand to car detailing and then to body and fender repair and painting—it was becoming a car shop.”

To enable those fledgling businesses, the organization runs a small revolving loan fund that operates on a peer lending model, which means that other borrowers in a cohort may chip in on a member’s loan payment rather than let it be delinquent. The First 72+ is unusual in other ways, too: it charges no interest on its loans, and may even accept service in lieu of monetary payments, if necessary.

But ultimately, says Orians, the organization aims to be a short–term fix. “We try to be a step towards accessing traditional loans from banks or credit unions.”

A groundbreaking Colorado program also found itself developing a small–business training program. In 2017, the unique Transforming Safety bill passed the Colorado legislature, dictating that $4 million of the state’s over $1 billion corrections budget be reinvested as grants and small business loans in two of the state’s communities with some of the highest rates of incarceration—Aurora and southeast Colorado Springs.

The Colorado Enterprise Fund (CEF), a CDFI, was one of two organizations tasked with administering the funding. But it became quickly clear that potential recipients—mostly formerly incarcerated individuals—needed more than just capital. “These folks aren’t necessarily ready for debt,” says Alan Ramirez, director of strategic lending with CEF. “They need the training and education and guidelines and a roadmap about how to operate [businesses] and launch.”

So Cory Arcarese, a CEF community lending adviser, partnered with a community-based organization to teach eight weeks of business classes to people who had recently been released from incarceration, funded by the Transforming Safety program.

After the first round of classes, though, one participant said to Arcarese, “I wish I learned all these skills before I got out [of prison]. If I’d had the skills then to start my own job, I wouldn’t have gone back to what I knew.” Instead, because he’d had a lag time after leaving detention, he found himself falling back into his old bad habits.

In response, Arcarese and her partners worked with Colorado’s Department of Corrections to offer the business courses inside men’s and women’s prisons. The classes, which began in March 2019, have been extremely popular; in one case, 90 people applied for 20 spaces in a class.

But not just anyone can participate. Students have to be within six months of release, and have to have viable businesses in mind. No hair salons, says Arcarese: “There’s enough beauty salons.” Many inmates have learned skills on the inside like welding and electrical work—lucrative jobs that can pay off big time with state contracts.

The eight–week course teaches a standard business curriculum that includes how to read a financial report, do search engine optimization, and hire employees. So far, about 120 people in three different institutions have graduated from it.

And now those students are being released from prison and are beginning to apply for loans, usually $10,000 or less. CEF is ready for them, says Arcarese. “If they’ve gone through the class, it certainly carries weight with us,” she explains. “By the time they’re asking for money, I’m pretty sure that their business plan is solid. I’m the one that’s worked with them.”

One of those borrowers was Brenda Davis, the dog groomer. She was just approved for a $7,500 loan from CEF and is waiting for it to come through. Applying for the loan was fairly easy, she says. “I had to do the business things, like create a cash flow sheet—all the things I learned and would’ve never known without that class.”

Soon, the trailer that she works out of will be finished with its renovations and the business will be up and running. “We’re going to be raking in the money here soon,” says Davis, a longtime pet groomer who says it’s a profitable field that doesn’t take a hit even when the economy dips.

Once things really get going, Davis says, she’ll hire some help—and it’ll be another former felon. She’s committed to that.

Is it not extraordinary to finally see such an article on Shelterforce – an article which in so many words acknowledges that socialism has been a disaster – that it has, by way of its judiciary – its complex of laws / police / courts / penitentiaries / and judges – been especially harsh on the poor and on minorities – and that the way out is in fact through free enterprise and capitalism ? One scarcely knows what to say. Bravo Amanda Abrams ! May your excellent article and implicit advocacy of anarcho-capitalism be the beginning of a long term trend 🙂

I was just placed on probation for a year and people are saying because of that I can not get an apartment. And the incident was 2 years ago.Do you know of anyone in Maryland that will rent to me? I am not a bad person I lost my temper at a mail woman who was stealing my packages and bills. I showed her a knife but I did not touch her. The courts gave me one year probation and now I am not being Able to find housing. Is there anyone in Maryland who can help me get a one bedroom apartment?

I would like to start a small trucking company with this long