Just Housing leaders celebrate after the Just Housing Amendment passed in April. Photo courtesy of Housing Action Illinois

Gianna Baker addresses a crowd at a rally in April, just before the Just Housing Amendment passed. Photo courtesy of Housing Action Illinois

Last year, Cook County—our nation’s second most populous county, which includes Chicago—took a historic step forward by passing a law that protects people who have an arrest or conviction record from housing discrimination. It’s estimated that the Just Housing Amendment, which went into effect at the beginning of the year, will give more than 1 million residents and their families a fair chance at securing a home.

This is a crucial win for racial and economic justice. Fair access to a safe, affordable home is fundamental to building a stable life and caring for yourself and your family. Where you live affects your ability to find a job, access education, stay healthy. People who have records, like everyone else, deserve a place to call home—but often this basic right is denied. That’s because landlords often turn down applicants who have records even when they meet other housing requirements, like annual income. When someone with a record goes to rent, data suggests that 8 times out of 10 they will be rejected, most likely because of the background check a landlord runs.

This affects a huge number of individuals. According to the Center for American Progress, one in three Americans has an arrest record before they turn 23, regardless of race or gender. To put this in perspective, that means that it is just as common to have a criminal record in America as it is to have a college degree.

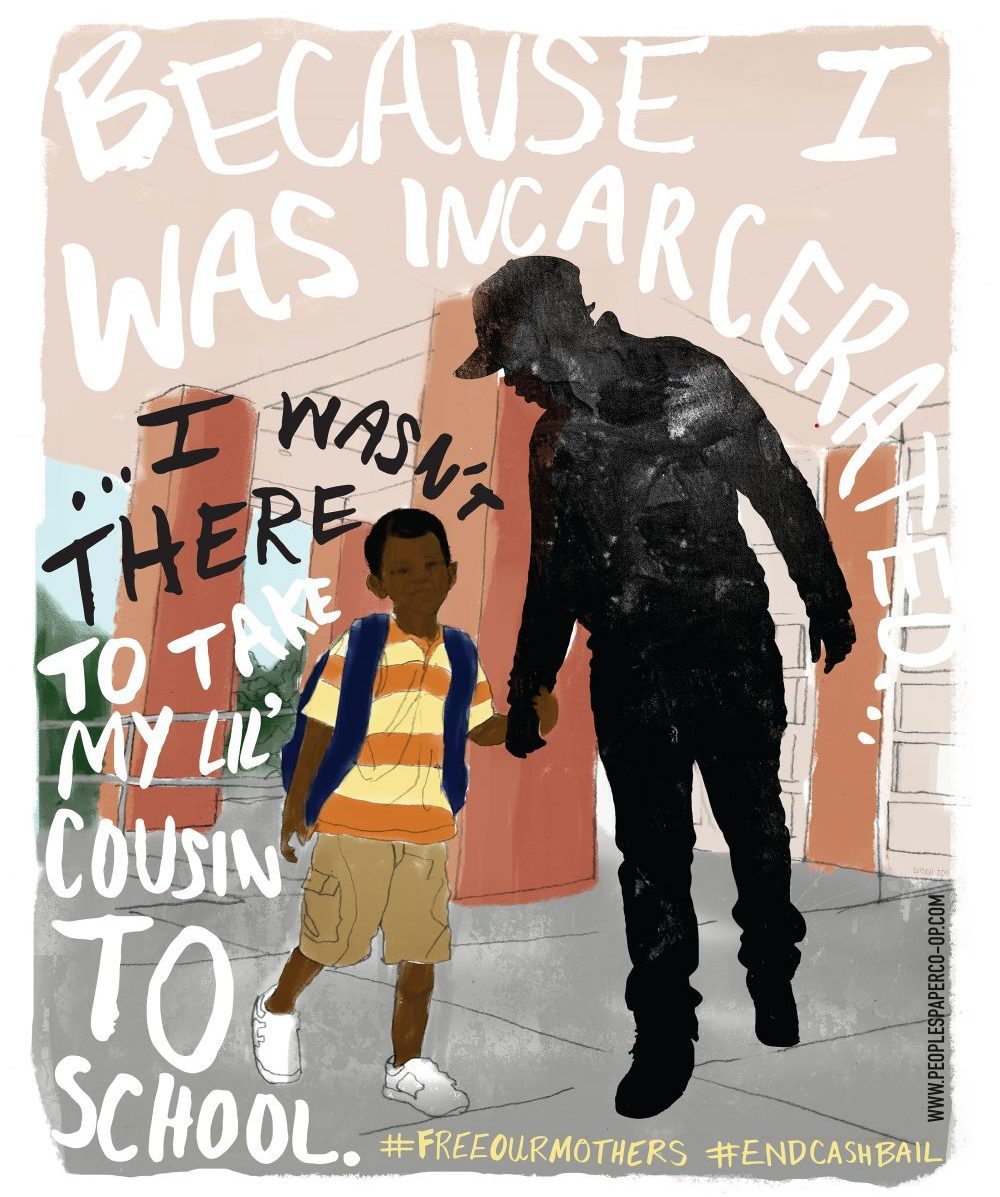

A person’s ability to find a home after an arrest or conviction matters deeply not just to them but also to their children and partners. Almost two-thirds of the prison population in Illinois—about 62 percent—are parents of children under 18, according to the Illinois Department of Corrections. Their ability to secure a good, stable home affects whether and how they are able to reunite with their children when released. Moreover, a study by the Prison Policy Initiative shows that in the United States, returning citizens are almost 10 times more likely to experience homelessness than the general public.

Because many housing providers impose blanket arrest and conviction record bans, people with records and their loved ones often experience housing instability. In The Ella Baker Center’s report, Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration, communities of color in 14 states, including Illinois, were surveyed. The report showed that 79 percent of survey participants were either ineligible for or denied housing because of their own or a loved one’s conviction history. Also, 1 in 10 survey participants reported that family members were evicted once loved ones returned home from prison.

Due to disparities in the criminal justice system, housing restrictions based on arrest and conviction records disproportionately impact Black and Brown families and people with disabilities. These policies are often an avenue for race- and disability-based discrimination.

Passing these protections is a win for everyone in our community. Stable housing opportunities for people with records are key to reducing recidivism, and each event of recidivism in Illinois costs more than $150,000, according to the Illinois Sentencing Policy Advisory Council.

The Just Housing Amendment was a long time in the making. Four years ago, in response to When Discretion Means Denial, a report by the Shriver Center on Poverty Law, a group of Chicago-area based housing and criminal justice organizations and individuals with records banded together under the name of the Just Housing Initiative and worked to dismantle barriers to stable housing for people with records.

Since the beginning, our coalition’s primary focus has been passing fair chance housing legislation at the county level. Co-chaired by the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance and Housing Action Illinois, the Just Housing Initiative grew quickly. By the spring of 2019, when the amendment finally passed, we encompassed nearly 120 organizations, including social service providers, community organizers, nonprofit housing providers, legal and policy experts, and housing and criminal justice advocates.

A steering committee of 12 organizations was introduced to determine strategy, organize supporters, and discuss the measure with commissioners, real estate agents, landlords, reporters, neighbors, and residents. This committee consists of the Alliance to End Homelessness in Suburban Cook County, Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance, Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, Community Renewal Society, Housing Action Illinois, Housing Choice Partners, John Marshall Law School Fair Housing Legal Clinic, Safer Foundation, Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law, Supportive Housing Providers Association, Westside Health Authority, and Woodstock Institute.

From beginning to end, the leadership, testimony, and advocacy of people with lived experience was critical to our campaign. Dozens of Just Housing leaders changed hearts and minds by sharing their personal challenges at multiple hearings and meetings, and our coalition emphasized that each passing day mattered for families who are struggling to find housing at this very moment—that justice delayed is justice denied. Each year, there are over 10,600 people who return home to Cook County from prisons in Illinois.

Over the course of four years, we spent countless hours in discussions with decision-makers and testifying at hearings. At various points, we thought the legislation would be introduced, but encountered delay after delay. Finally, last spring, Commissioner Brandon Johnson, chief sponsor, stepped forward to introduce the Just Housing Amendment—his first piece of legislation after being elected to represent the 1st District. With the support of Cook County Board President Toni Preckwinkle and additional co-sponsors, we braced ourselves for the board’s vote on the measure in April 2019.

The day before the Cook County Commissioners were scheduled to vote, more than 50 Just Housing leaders showed up at a committee hearing in support of the amendment, some of whom addressed the committee. “I am not my record,” they told legislators, a refrain carried throughout the campaign as we worked to help people understand the issue.

“People don’t know the whole story,” Just Housing leader Willette Benford told the Cook County Board during her testimony in April. “They just look at the [background check] and they’re immediately afraid. They don’t know the details, and they just make the assumption that everyone’s still guilty. Then they deny you housing, which is just a basic necessity—and then where else are you supposed to go?”

Veteran and community leader Troy O’Quin also testified at the public hearing in April. “It only takes a second to break the law, but a lifetime to live with the consequences,” he told commissioners. “One second, one crime, one serious lack of judgment . . . in America, this can be a life sentence.” O’Quin didn’t show up on his own that day. When his 9-year old twin daughters stepped up to the podium to deliver their own testimony about how their father’s difficulties in finding housing affected the entire family, the girls brought tears to listeners’ eyes.

Some leaders within our campaign shared experiences of living in their cars, at shelters, couch surfing, and living in substandard housing conditions because despite having adequate income to rent, landlords wouldn’t give them a shot.

We also worked with nonprofit housing providers and landlords who believed in the campaign and wanted to speak out in support. Anne Holcomb, an owner of a small apartment building, testified at the hearing and also shared her support in an op-ed. “Beyond any question of fairness, keeping people with criminal records out of housing doesn’t keep our communities safe,” she wrote. “As landlords, we can help returning citizens come back into society.”

The next day the Cook County Board of Commissioners voted, and the Just Housing Amendment passed with almost complete support—only 2 of the 17 commissioners voted no.

Although we celebrated the historic win, the Just Housing Initiative faced challenges even after the vote. Originally, the amendment was supposed to go into effect at the end of October 2019, but the rules for implementation bounced between committees and votes in what the Daily Line’s Alex Nitkin aptly described as a “game of bureaucratic ping pong.” In the end, we spent seven months advocating for the best ways to implement and enforce the legislation, negotiating with the opposition, and developing draft rules with the Cook County Commission on Human Rights. Areas of contention included the length of a look-back period—how many years into an applicant’s conviction history a landlord can look—as well as whether a unit would be held off the market while tenants contest the findings of a background check. As the months passed, we worried that the rules for implementation would not uphold the spirit of the original legislation, or that delays would continue into the next year.

Given this long road, it was a relief when the Cook County Board of Commissioners finally passed implementation rules in late November 2019, clearing the way for the Just Housing Amendment to take effect at the end of 2019. We support the final rules, which:

- Ensure that housing providers and housing authorities do not consider certain aspects of criminal records—such as arrests, juvenile records, and sealed and expunged records—when making housing determinations;

- Protect tenants and homeowners from being denied housing based on convictions greater than three years old; and

- Require housing providers to give a fair chance to applicants with a conviction that is less than three years old by conducting an individualized assessment, considering factors such as the nature of the offense; evidence of rehabilitation; and an applicant’s demonstrated ability to be a good renter, neighbor, and community member.

Now, the Just Housing coalition is shifting focus to education and outreach with would-be tenants, landlords, and members of the public. We are eager to build understanding, expand opportunities, and create a stronger, safer, more stable community for everyone in Cook County. And even beyond Cook County, we see positive movement on this important issue. Shortly after the Just Housing Amendment passed in Cook County in April 2019, complementary state legislation passed the Illinois General Assembly. The bill, Senate Bill 1780, which went into effect Jan. 1, amends the Illinois Human Rights Act and makes it a civil rights violation to refuse to engage in real estate transactions, or otherwise make housing unavailable, to any buyer or renter based on an arrest record that did not lead to a finding of guilt, a juvenile record, or a record that has been ordered sealed or expunged.

These policy successes in Illinois come as the movement for access to housing as part of criminal justice reform is gaining momentum across the country. Fair-housing measures for people with records have passed in jurisdictions such as Washington, D.C.; Seattle, Washington; Detroit, Michigan; and Richmond, California. Activists in at least a dozen major cities are currently campaigning to pass their own ordinances. At the federal level, in July 2019 Sen. Kamala Harris and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez introduced the Fair Chance at Housing Act, which would help ensure that justice system–involved people have access to federal housing assistance.

Increasingly, people across the nation are recognizing that expanding access to good homes—and doing so through fair chance legislation—is an integral component of criminal justice reform.

Kristin and Gianna, I think you will find that the reason there are so many minority ex-cons, is because of the Progressivist War on Drugs, the follow on project of Prohibition, the first large scale Progressive project. Prohibition, the Progressives explained, ‘would empty out the jails’. Alcohol was said to be the root cause of crime. By banning alcohol, a new found sobriety in the people would prevent them from committing crime. In fact Prohibition was a disaster which begat the initial destruction of once peaceful prosperous American cities. Chicago never really recovered. The follow on War on Drugs engendered the full on destruction of city after city in the US – Baltimore, St. Louis, Newark, Chicago. The point is if you simply concentrated your energies toward abolishing the Progressivist War on Drugs project, the project which swept up tens of millions of minority individuals and turned them into felons, you would have no need to advocate for a follow on Progressive program to try to repair the damage done to the victims by the first Progressivist project.