Intriguingly, ABCD has tended to focus on intangible assets such as skill sets, commitments, and networks that derive from people, associations, and institutions. Sometimes I’ve heard of ABCD processes that focus on a particular material asset, like a historic district or beloved park. But rarely are abandoned buildings and dumped-on lots counted in the asset category.

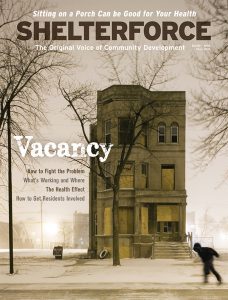

And no surprise—they are damaging to the community around them in myriad well-documented ways. They harm the health of nearby residents, as well as their quality of life, and at some point if there are too many abandoned buildings, they can seriously hamper the ability of a neighborhood to function. And yet, thinking of abandoned properties as merely problems we wish would go away, rather than opportunities that we need better tools to access, feeds into some of the less productive ways vacant properties have been handled over the years—selling them off to the highest bidder, selling tax liens to investors, refusing to let community groups access vacant lots.

If I heard a theme in the conversations I had in preparing this issue, it was the idea that getting a grip on the challenges that are generated by abandoned properties (and they should not be underestimated) works better when we approach them with the attitude of opportunity.

A large amount of vacant land can be an opportunity to create green infrastructure. An activation project on a small vacant lot can be an opportunity for neighbors to work together and a launch pad for them to have greater influence on planning for their neighborhood. A citywide vacant-lot cleanup program can be not only an opportunity to improve health, but provide job training and jobs to returning community members. The right adjustments to state and local policy can create better incentives and more ability for the public sector to transfer abandoned properties to responsible owners and thereby enable opportunities for new homeowners and responsible small developers. A new for-profit buyer for a partially vacant run-down development could be an opportunity to create a partnership to tackle a sky-high asthma rate.

None of this is to underestimate the challenges. Particularly, as Alan Mallach points out in his overview piece that outlines two different vacancy crises, in regions dealing with “hypervacancy” where the housing market has broken down, the effects are extremely serious. All the more reason it is imperative to see possibility. Now, seeing possibility does not mean hoping for a pie-in-the-sky return to bygone development patterns. Expecting a revival of the same kind of industry that made the city grow in the first place almost never makes sense, and even assuming that a residential neighborhood will return to the same level of density it once had can limit creative thinking. But remembering that land is the most basic of municipal assets—hopefully to be turned toward serving the public good—is a better place to start.

Meanwhile, in our health supplement, an Indianapolis arts center also spotted the opportunity in an often overlooked part of the home—porches. Recognizing that loneliness and social isolation are bad for the health of both individuals and neighborhoods, the Harrison Center for the Arts started a series of porch parties to bring neighbors together. This is a great example of the aligning of arts, health, and community development. The arts center arrived at porch parties from an arts path, supported by its work doing oral histories and community gatherings. But the parties could just as easily have been launched by a public health group concerned with the effects of social isolation, or by a community development group looking to strengthen its community or lay the groundwork for community organizing. I suspect that the arts organization might have been the most successful at it, however, because its perspective allowed it to focus on the experience of the participants and not try to layer other things onto the parties (health screenings, for example, or planning charettes) that might make participants feel more like they were participating in a program than actually forming authentic connection. In an outcome-driven world, this, perhaps, may be a lesson we can learn from the arts sector. Connection is valuable enough to prioritize. The outcomes will follow.

Comments