Vacant lots sometimes serve as unofficial parking lots, and dumping grounds for abandoned cars, soiled mattresses, and household trash. Photo by Maggie Loesch

A once-vacant lot in Philadelphia that has been cleaned. Studies show that vacant lot remediation reduces firearm violence in the neighborhood and increases property values. Photo by Maggie Loesch

“It’s a nuisance,” says Andrea Smith of the vacant lot next to the house where she has lived for 56 years.

Smith, a South Philadelphia resident, has watched as the lot repeats a cycle of destruction and repair—it’s trashed and the neighbors have to clean it up. Her sentiment about vacant lots was echoed by residents in North Philadelphia, like 59-year-old auto technician Al Bethea. “People dump on them, trash them. They need to take care of them,” says Bethea.

For anyone walking through the residential sections of Philadelphia, the sheer volume of vacant land is impossible to ignore. There are about 40,000 vacant parcels within Philadelphia’s city limits, according to Keith Green of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS), a major entity addressing the problem. The city’s most disinvested neighborhoods have swaths of them, flat land stretching for blocks at a time.

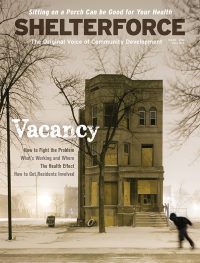

The properties often become unofficial parking lots, and their worst are dumping grounds for soiled mattresses, abandoned cars, and household trash. These blighted properties signal both public and private neglect, which can lead to crime and trauma caused to those who witness it and other unsafe behaviors, according to a February 2018 study by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University.

Cleaning and Greening the Lots

Philadelphia’s innovative solution to this demoralizing problem involves a contract with PHS, which due to its preference of hiring locally, partners with neighborhood businesses—which tend to also be owned by people of color—to “clean and green” the lots and install simple wooden fences. Each lot is cleared of trash and overgrown vegetation, and given new grass seed and a fence, and trees if size allows. The work is performed by 15 city-based firms—which strengthens the local economy—as well as 18 smaller organizations contracted for PHS’s Community LandCare, says Green.

The LandCare program takes care of roughly 30 percent, or 12,000, of the city’s lots annually, for only 12 cents per square foot, says Green, who is also the program’s director. (Average landscaping costs in Philadelphia are 9 to 15 cents per square foot, not counting tree-trimming.) According to Green, the lots don’t have to be under city control to be eligible for cleanup, and the goal is to eventually get all of the city’s vacant lots into the program. Private owners of neglected lots are put on notice and have 10 days to clean up their lots. If they do not, then the city, and subsequently PHS, are granted access to the property.

The cost for an initial cleanup is $1,500 per lot, and bi-monthly maintenance averages $300 per year, per property. The charges are recorded as a lien on the property and must be paid before the lot can be sold. This is typically done as a way to get properties out of the hands of irresponsible owners. Unfortunately, liens can make properties less appealing to purchasers, including budget-conscious nonprofits.

Lot selection is based on complaints filed by community members, as well as proximity to other assets in the neighborhood. Lots near commercial development and schools are given priority, says Green. PHS also tries to form “target areas,” about five blocks square in area, where a cluster of lots is addressed at once. The city council also has a role in selections. Each year, 2,000 new lots are added to the existing inventory.

The Importance of Green Space

Some neighborhood residents have embraced the new green space, adding picnic tables at some, planting gardens in others. Revamping the lots “gives people the ability to see what could potentially be there,” says Green.

While the city can’t declare that these types of additions can stay indefinitely, the uses provide at least a temporary community gathering space. In areas with greened lots, residents also enjoy decreased neighborhood violence and better mental health than they would in areas with untouched lots. “Green space in and of itself is important for mental health benefits,” said Eugenia South, a co-author of the 2018 university study and assistant professor of emergency medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

Tracy Jamison, 54, has noticed that difference after several lots were renovated in the area of North Philadelphia where she’s block captain. “The lots used to have old cars and trash piling up. Now kids bring coloring books and use the space for camp,” she told the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It makes the community happier.”

PHS’s $6.5 million annual contract comes from Philadelphia’s General Fund and the Division of Housing and Community Development, with less than 1 percent coming from federal CDBG dollars. Started in the 2000s during the Neighborhood Transformation Initiative (NTI) of then-Mayor John Street’s administration, LandCare seeks to maintain vacant lots as a way of avoiding more problems in neighborhoods, thus saving money. For instance, remediating abandoned buildings and lots reduces gun violence by 39 percent, according to a 2016 study by the University of Pennsylvania. The study estimates that each dollar spent repairing vacant land yields a direct $26 rate of return to taxpayers. The study also concluded there were indirect savings of $333 per dollar spent through ripple effects such as reduced violence. “As a public health issue, the costs of firearm violence in the United States are large and extend beyond the loss of life and emotional burden for affected individuals and families” the study notes. “Significant costs are also borne by taxpayers and society at large, with more than $48 billion per year in medical and work-loss costs alone.”

Fixing up abandoned land has also been shown to increase property values of the surrounding neighborhood by 17 percent, according to a 2006 report from the Wharton School of Business of the University of Pennsylvania.

Doing minor landscaping and installing the now-familiar wooden fences on vacant properties shows that somebody cares about the area, and that in itself helps prevent further disorganization, violence, and divestment that was signaled by trash-filled, unkempt lots. Philadelphia’s former director of housing, John Kromer, described this partnership in his book, Fixing Broken Cities: The Implementation of Urban Development Strategies, as “[t]he single activity that had a transformative impact on neighborhoods and can be linked directly to NTI investment.”

Hiring Formerly Incarcerated Workers

LandCare also supports a workforce development program. PHS runs Roots to Re-Entry, which helps those leaving the Philadelphia prison system transition back into mainstream society. Those who qualify for the program participate—while still incarcerated—in certificate training with Temple University’s landscape architecture department to learn about tools, machinery, horticulture, ecology, and landscape design, says Green. Upon their release, they take part in a 12-week internship with PHS where they put their skills to work. After this, they have the opportunity to interview with the local landscape crews PHS contracts with. On average, each contractor hires two to three formerly incarcerated workers each year. To date, 100 workers have obtained jobs thanks to the program, according to PHS communications manager Kevin Feely. The recidivism rate of Roots to Re-Entry program graduates is 30 percent, compared to 65 percent for people who have been incarcerated but not participated in the program.

PHS also runs a “boot camp” training for people who have been released between one and five years prior but did not receive training in prison. This six-week training for entry-level positions also provides participants with a case manager, work clothes, and a stipend averaging $300 a week. Roots to Re-Entry programs are funded through the Philadelphia Department of Prisons as well as private donors.

The Broader Objective

Some cleaned-and-greened lots are later developed. According to Green, about 20 percent of PHS sites have been developed in some fashion, including over 1,000 homes and 150 commercial properties. Another 130 sites have become permanent green spaces. If a lot is owned by the city, residents can make a pitch to local officials for the site to become permanent green space if redevelopment potential has not been identified.

But development is not the main goal of the program. The broader objective is to improve the quality of life for residents who live near abandoned lots, to reduce crime, and to invest in local entrepreneurs. Remediating vacant lots increases property values in the surrounding area, and reduces gun violence, which not only saves the community money, but most important, improves neighborhood safety. A safer neighborhood leads to the improved health and well-being of residents—by reducing crime, there’s a reduction in fear, stress levels, and depression, studies show. Spending more time in green spaces can also help reduce depression, by as much as 68 percent in some cases.

Because of its relatively low cost and widespread benefits, remediating abandoned lots could be the biggest bang for a city’s buck.

I would love to be able to build my retirement home in Philly. Since I cannot go up and down the steps I need to build s one story house and be close to my family and friends. I would need two lots since most are not wide enough to build a garage next to it. I also want to be able to plant flowers and vegetables. I like the following zip codes 19120, 24 and 34.

Thank you in advance for your help.

Rosa Marrero Tel: 267-512-9019 or 939-292-2227 Email: [email protected].