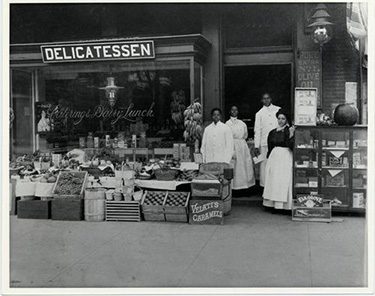

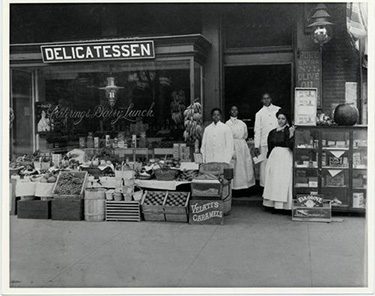

The Underdown Family Delicatessen on the corner of 14th and S St. N.W. , Washington, D.C., circa 1904. Mr. and Mrs. Underdown shown with two other employees. Photo by Addison Scurlock, photographer

Recently there has been broader discussion about the Racial Wealth Divide—the current (and shockingly large) difference in wealth between Blacks and whites, along with the history of how it got to be this way. This discussion is extending beyond academic and policy settings and into a more mainstream media because it’s clear that far too many Americans—of all races—do not know the story behind what we see in communities around the country. Pulling the curtain back may provide the context needed to make concrete amends, as well as catharsis for an entire group of Americans.

In the 20th century, a common political talking point was that poverty was a moral failing that just needed a good bootstrapping lecture and some tough love. In these new conversations, we’re moving on from that to acknowledging that our government and many major American institutions were instrumental in stripping Black people of wealth. For example, Black people were excluded from many of the income and wealth-building programs that helped build the foundation of white Americans’ wealth today—programs like Social Security (which when created in 1935 excluded farm and domestic work, which were the majority of jobs black people held at the time), and the GI Bill, which helped provide financial aid for education, mortgage loans, and small-business loans to World War II veterans.

Former New York Times writer Bob Herbert’s new documentary, Against All Odds, The Fight for a Black Middle Class, provides a timeline of the discrimination and economic setbacks Black people suffered at the hands of white America from Emancipation Proclamation through the Great Recession. The timeline of events in the documentary positions the “fragile” state of the Black middle class as one that operates perpetually in a series of considerable gains but even larger losses.

Speaking as keynote at a conference earlier this month at Harvard that explored the relationship between the nation’s colleges and slavery, writer Ta-Nehisi Coates praised Georgetown University’s announcement in 2016 that it would give preferential status in its admissions process to the descendants of slaves whose free labor the university profited from, as well as the 272 individuals who were sold off when the school was struggling financially.

In his address, Coates suggested that other colleges founded and run on profit from slavery should also institute reparations programs. Despite Harvard’s own deep ties to slavery, the school’s actions have been largely symbolic so far, including removal of a slave-holding founding family’s coat of arms from its law school. With this conference, it seems that there may be hope for more effectual action. Though African-American college graduation rates slowly climb upward, they still lag significantly behind those of whites, and foretell of lifetimes of lesser earnings. And a recent report shows that even a degree may not be enough.

A joint report from Demos and the Institute on Assets and Social Policy concludes that whites are five times more likely than Blacks to receive a large monetary gift or inheritance from relatives, enabling them to start out on a more secure financial footing. This money may replace a student loan or provide the down payment on a home—both investments that lead to greater assets in the long term and potential wealth to be passed down to future generations. The report’s findings also counter some of the middle-class “rules” that many Americans believe prevent people from entering, such as “raising children in a two-parent household does not close the racial wealth gap,” and “spending less does not close the racial wealth gap.”

The Corporation for Enterprise Development has been informing the field on the wealth gap for years now, and began its Racial Wealth Divide Initiative in 2015 to formalize a comprehensive approach to educating people about and addressing wealth inequality. A report it released last year, The Ever-Growing Gap: Without Change, African American and Latino Families Won’t Match White Wealth for Centuries, sounded a warning to policy makers that pushes change as not only a moral imperative, but a national economic one. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA) introduced a House resolution in 2015 that would formally recognize the wealth gap as such, and Federal Federal Chair Janet Yellen called the widening gap “extremely disturbing.”

To return to the character flaw/failing part of this topic is important, and I think it would go far to acknowledge, on a very large stage, the forces that were used against the descendants of enslaved people to reinforce and maintain their lesser economic standing in American society. Within the African-American community, there are sayings and centuries-long held beliefs about our propensity to work and lack of financial common sense—no doubt carried over from the overseer book of catchphrases. But would a clear paper trail of guilt allow us to collectively let ourselves “off the hook,” and free many from a damaging mindset? At the end of his essay on the compared values of Black and white-owned homes in the South and the social structures that have led to their great disparity, Robert Reece says, “We must remember that the past is not the past. It is more than simply the bedrock of today, but the roots from which we sprang, directly shaping events in ways that we do not always completely understand.”

If we allowed ourselves to fully remember this past, maybe the only hindrances that remain for future generations will be the vestiges of actual, on-the-books discrimination.

Comments