This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Discrimination in the Marketing & Maintenance of REO Properties

[Editor’s note, 2023: This post, and the entire series, was also posted on Race-Talk, a blog hosted by the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, but is no longer available there.]

—

What a difference a generation makes. National People’s Action got its start in the 1970s working against bank redlining—the practice of banks systematically starving low-income and communities of color by denying credit. NPA found success with the passage of the Community Reinvestment Act, which made redlining illegal and in countless communities around the country, neighborhood groups and banks entered into CRA agreements to foster good, safe investment in community development and housing.

By the 1990s, instead of suffering the credit drought of redlining, communities of color were inundated with a toxic flood of predatory subprime credit. Lenders systematically steered borrowers of color into high cost loans regardless of their income or credit profile. Wall Street and the banking industry realized, why ignore communities of color when you can suck them dry?

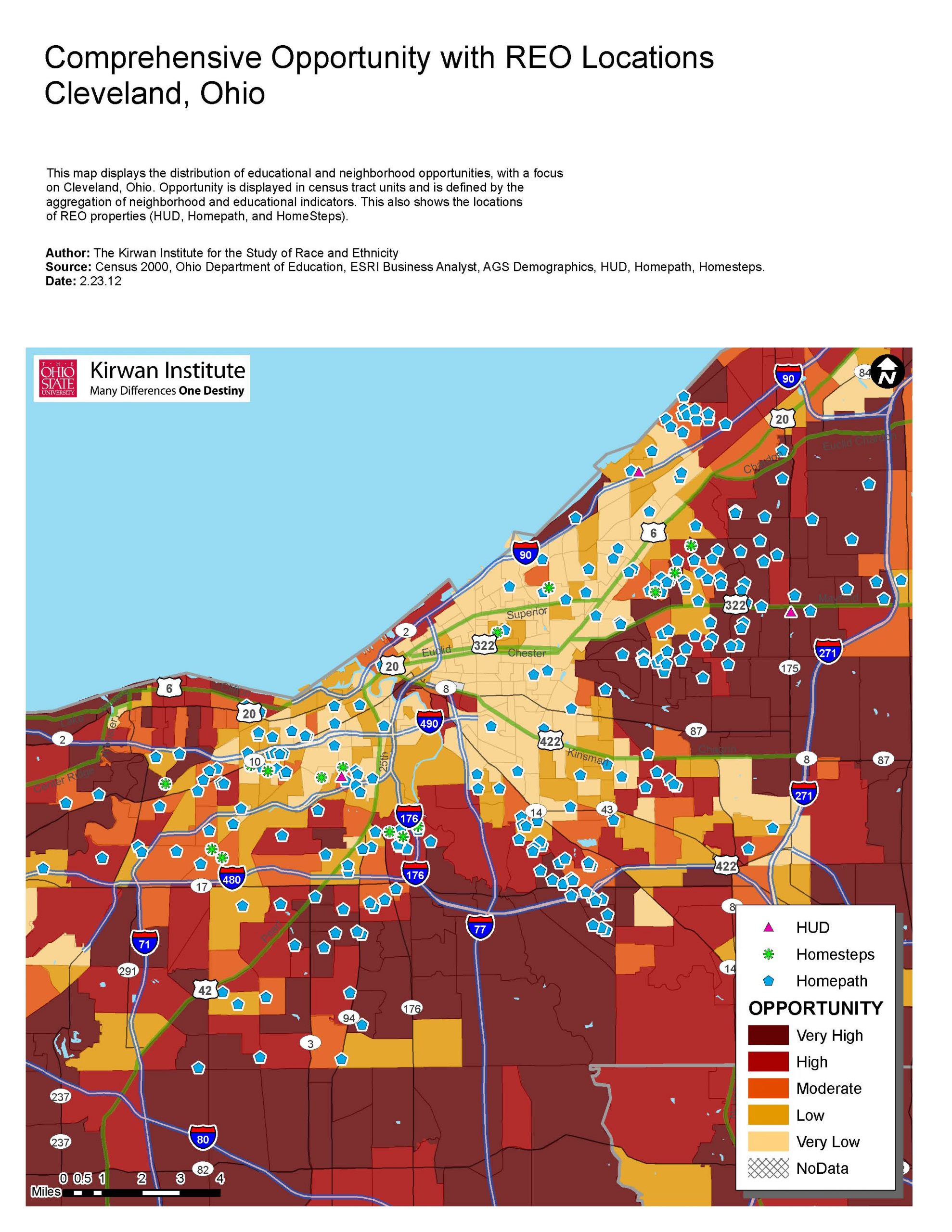

After this strategy blew up in the face of Wall Street—and all of us—with the economic collapse, we were promised that Wall Street had learned its lesson. No more would it systematically strip communities of wealth, which it turns out destabilizes the whole economy. Unfortunately, these promises have turned out to be hollow. Recent research reported from the National Fair Housing Alliance shows that even as we struggle to bring our economy back, Wall Street and the banks are continuing their pattern of abuse by failing to maintain and market their real estate owned properties in communities of color as compared to their treatment of those homes in predominantly white communities.

Why is this pattern repeating itself? The very structure of our economy and financial system functions to reinforce institutional racism and encourage destructive practices. Our financial system has become so consolidated, so huge and so far removed from the communities it is supposed to serve that the interdependence between the success of families and the success of the mega-banks has completely broken down.

Traditionally, a bank took root in a community and its fortunes rose and fell with the fortunes of that community. It was in a bank’s self-interest to see its community thrive; more family deposits led to more business and mortgage lending; more stability and jobs led to growth in wealth and stability for the community and more profit for the bank. In the example of the Community Reinvestment Act, once local banks were forced to serve all of the communities around which they were located, they began making good loans in communities of color and low-income communities, and they saw an increase in wealth, profit, and prosperity. But this system of interdependence has completely broken down and with disastrous consequences.

From 1984 to 2003 the number of banking institutions in the United States went from just over 15,000 to fewer than 8,000. At the same time, the asset size of those institutions went from $3.3 trillion to $9.1 trillion. Since the financial crisis, the situation has gotten even worse with total the total number of commercial banks numbering approximately 6,500. And, staggeringly, in 2010, the top 10 banks in the U.S. held a full 50 percent of national deposits.

These mega-banks control the market and, in consequence, control most of the economy, but have no tether to the success or failure of individual communities. Lack of training and experience with financial institutions in some low-income communities and the pernicious stain of overt individual and institutional racism have left many low-income communities and communities of color especially vulnerable to financial exploitation, and the mega-banks and the Wall Street behemoths have exploited these vulnerabilities. With no motivation beyond next quarter’s profits, the big bank business model of “disposable communities” appears to make good financial sense.

But we don’t have to look to the distant past to see the lunacy of this position. We’re all – with the exception of big bank executives – still deeply feeling the effects of the financial crisis brought on by this madness, and communities of color, who suffered first, continue to suffer most. Beyond the clear immorality of it lies an economic house of cards that is teetering once again. Reports such as the NFHA REO study, the persistence of bank foreclosure fraud, and recent press showing a return to predatory credit prove that the banks are intent on driving us back into the economic ditch – remarkably along the same road.

With big bank CEOs locked away in office towers often thousands of physical miles and millions of psychological miles away from the neighborhoods they’re destroying, the opportunities for direct accountability are few. This Spring, NPA groups, along with dozens of other groups, will be bringing homeowners, farmers, retirees, and community members directly to several big bank and other corporate shareholder meetings to directly confront CEOs. While these events are a crucial opportunity to shine a light on destructive bank practices and force CEOs to come face to face with real suffering, once a year is not enough.

We need a radical restructuring of our economy. We need economies that operate locally, where profit and wealth that are generated in the community stay in the community. We need banks and business that are rooted physically where they do business and that are accountable to their customers and workers. In short, we need true community economies.

Several exciting experiments are underway across the country that are testing these ideas and succeeding, many in communities of color. The Alliance to Develop Power in Springfield, Massachusetts, began with organizing subsidized housing resident together to purchase their building and now owns several affordable housing developments, cooperatively owned businesses, and is in the process of starting their own money services bureau, the first step to their own community bank. PUSH Buffalo has been tackling the issues of environmental stewardship with job creation by training local residents in energy efficient weatherization, using local lots for community gardens and organizing for more community ownership of affordable housing. There are many other examples and thousands, even millions more are needed.

No American community is disposable and the time has long since come to allow anyone to treat them as such. Together, we can reclaim our communities.

—

This series is a collaborative effort under the Compact for Home Opportunity/Home4Good campaign and builds on the disparities illiustrated in the National Fair Housing Alliance report, “The Banks Are Back, Our Neighborhoods Are Not.” Those disparities are used as an entry point to discussing the issues of REO properties and equal opportunity that surround it.

Blog series contributors include Alan Jenkins of the Opportunity Agenda; Jillian Olinger of the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at the Ohio State University; Debby Goldberg of the National Fair Housing Alliance; Miriam Axel-Lute of the National Housing Institute; Liz Ryan Murray of National People’s Action; and Janis Bowdler of the National Council of La Raza.

Comments