This article is part of the Under the Lens series

Discrimination in the Marketing & Maintenance of REO Properties

This post is part of an ongoing series based on the National Fair Housing Alliance report, “The Banks Are Back, Our Neighborhoods Are Not,” that examines ongoing discrimination in the marketing and maintenance of bank-owned foreclosed properties.

This post, and the entire series, is also posted on Race-Talk, a blog hosted by the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity.

—

We now know that once again, the banks are engaging in practices that are harmful to our communities of color. A recent report by NFHA shows— literally, with disturbing pictures—the racially disparate maintenance of bank REOs; discusses the blighting effects such properties have on their surrounding communities; and the need for banks and other holders of REO to be held accountable. But besides anti-discriminatory enforcement—which is critical—what is the role of government in ensuring these properties act as stabilizing forces in hard hit neighborhoods, support the ongoing community revitalization work that has happened at the local level throughout this crisis, and connect people to opportunity through these properties?

What if the government created an initiative that met these affirmative goals with its own REO inventory? After all, the federal government owns about half of the country’s REO inventory (through HUD, Fannie, and Freddie).

The Federal Housing Finance Agency announced in August 2011 the Real-Estate Owned Initiative, which includes new pilot programs designed to unload REO properties from Fannie and Freddie’s balance sheets in an effort to stabilize neighborhoods and clear the market of distressed REO properties. The first pilot transaction began in February 2012, which was targeted to some of the hardest hit metropolitan areas (Atlanta, Chicago, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and parts of Florida). Under this pilot program, pre-qualified investors will be able to purchase pools of GSE single- family REOs that they must then rent for a specified number of years. There is much to recommend the program, namely the potential to stabilize severely distressed neighborhoods and markets, and provide rental relief in places that are experiencing higher rental demands. There are two significant flaws, however. First, there has been no consideration of the obligation to meet the goal of affirmatively furthering fair housing (AFFH) in the REO disposition strategy; and second, there has been no clear community development considerations articulated in the disposition strategy.

In a letter dated in September 15, 2011, housing advocates from around the country responded to FHFA’s Request for Information to point out the oversight. Advocates pointed out that the AFFH duty clearly applies to this initiative, not only in protecting vulnerable communities of color but also requires the federal government to expand housing choice for protected classes outside of racialized concentrated areas of poverty. In other words, government has an affirmative duty to open up access to “high opportunity” communities—those communities that enjoy economic and employment opportunities, affordable housing, health care and transportation options, and quality schools.

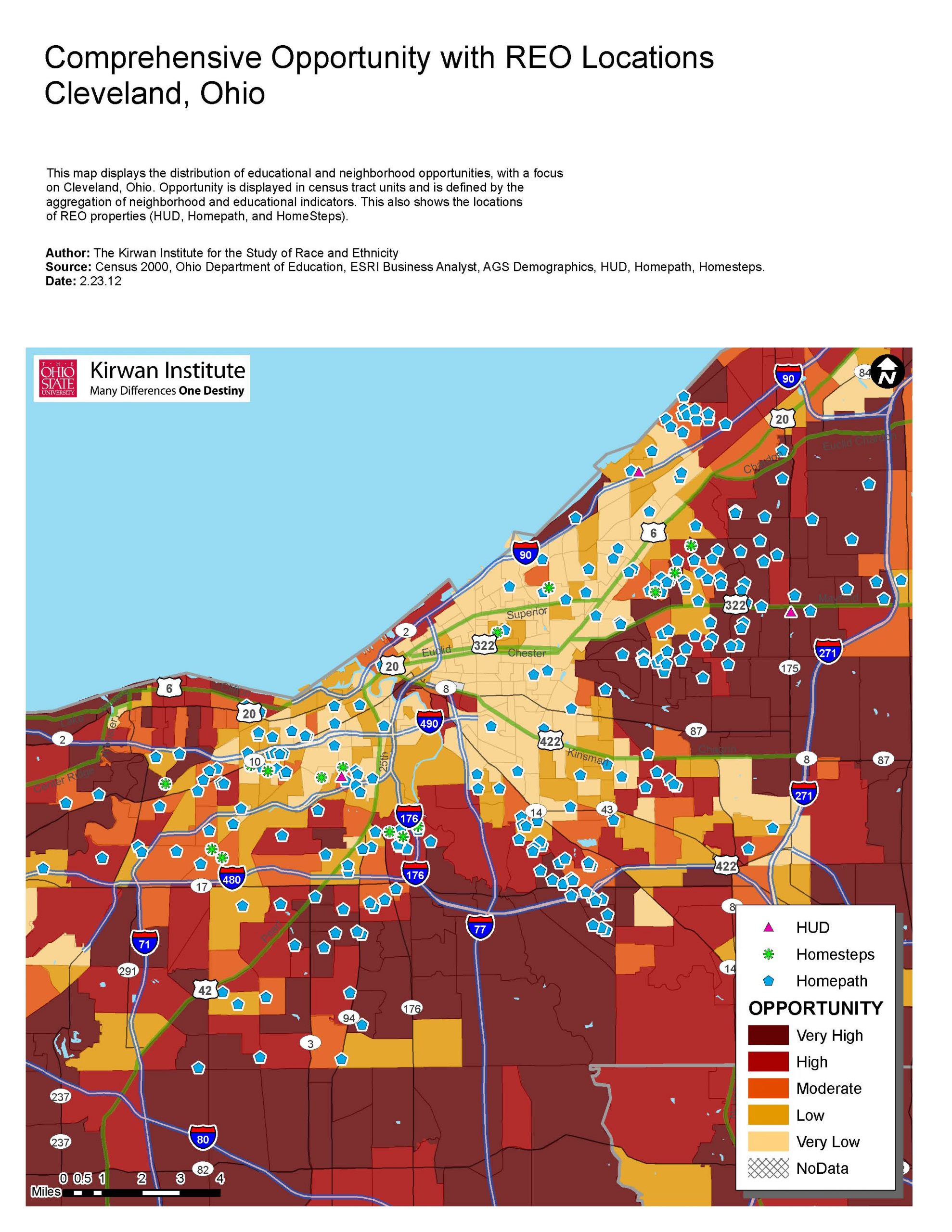

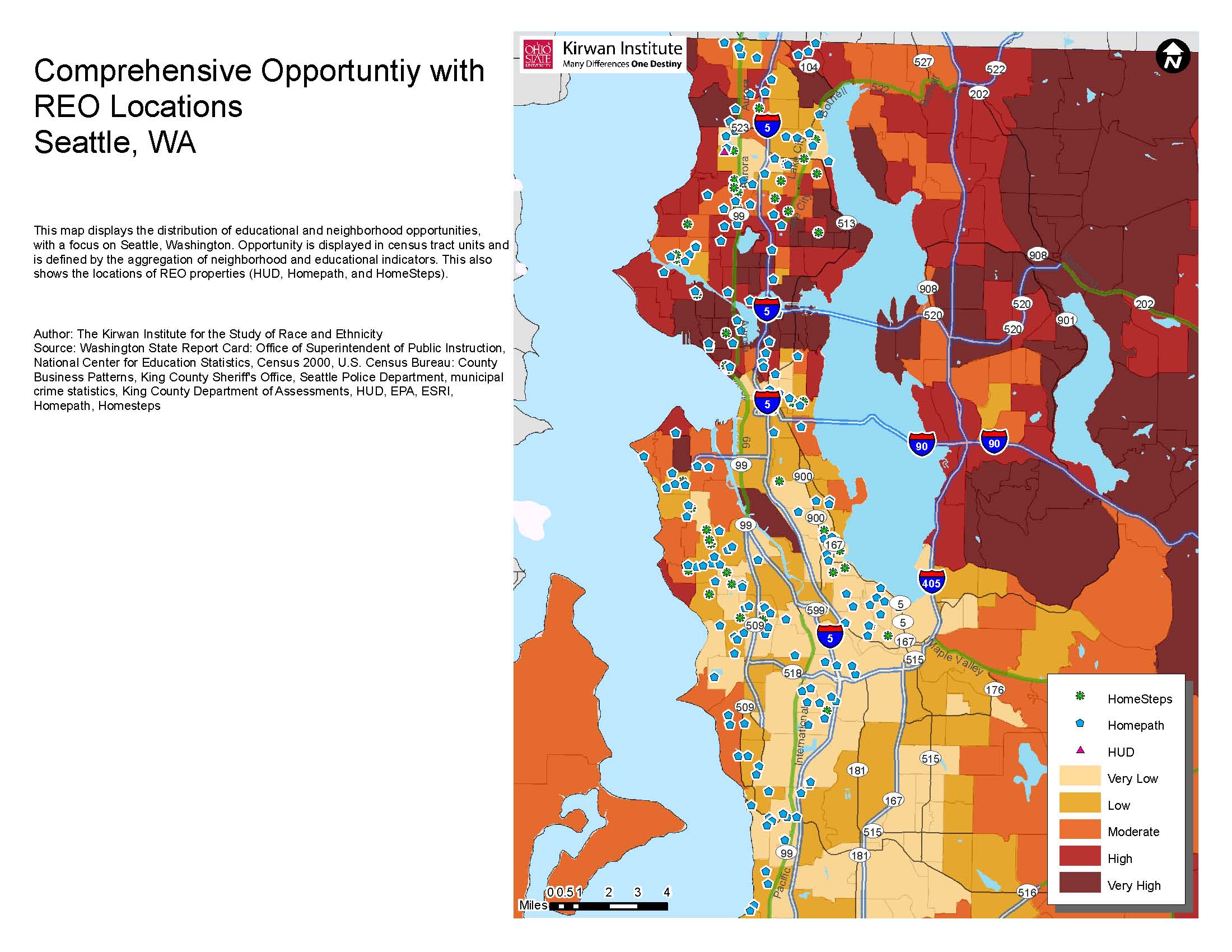

In partnership with the Poverty & Race Research Action Council and the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, Kirwan is working to expand fair housing opportunities for low income families by advocating the rental of government-owned foreclosed properties in higher-opportunity neighborhoods. As part of this effort we have mapped REO location on opportunity. Below is an example of Seattle, WA, and Cleveland, OH showing the location of FHA, Freddie, and Fannie REOs.

As shown in the maps, there are a substantial number of REOs in higher opportunity areas. While it is important that REO properties be returned to productive use in distressed communities (the lighter colors on the maps), it is equally important to ensure access to these REOs in high opportunity communities for low income households and households of color. Many of these higher opportunity areas continue to be marked by segregation, the legacy of past legal discrimination in the housing market, and the continued discrimination in housing (and credit) even after such discrimination became illegal. Including fair housing considerations in the disposition of REO properties helps the government meet its AFFH obligations.

Poverty & Race Research Action Council and the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, in conjunction with NAACP and the National Urban League, submitted a “Proposal to Incorporate an Opportunity Framework to Transition REO Property into Rental Housing” to FHFA on ways to structure such access. The recommendations include the need for geographical distribution of REO rental properties to include REOs in high opportunity areas; a bidding process that ensures affordable and fair housing goals are incorporated; adoption of a “first look” strategy in high opportunity areas for affordable housing developers and operators; new financial products to help facilitate these transactions; and affirmative marketing of the properties by investors.

There is also the question of which properties will be most appealing to investors out of these pools. Areas that will draw longer term buy-and-hold will be in areas of better opportunity, where the housing market is stronger. The properties themselves will have low enough acquisition costs, and high enough rental demand, that they can still produce positive returns. But what about those properties in the older, more distressed neighborhoods? These REOs are likely to languish. They require too much rehab and investment to produce positive returns for the investor. The longer such properties remain in limbo, the more damage they do to these communities.

This is not to suggest that the REOs in lower opportunity areas should be written off or potentially worse, left for grabs. In fact, quite the opposite is true. Numerous articles (here's one from the Washington Post and another from the New York Times) are coming out now that show that private investor appetite for REOs is increasing, and while some may view this as a positive, in terms of clearing some of the backlog in the market and slowing further decline, there is also reason to be extremely cautious about this new development. For one, this is a new experiment for investors—becoming landlords of a massive portfolio of scattered housing— and the risk that these properties are mismanaged and continue to deteriorate is real.

Even more fundamental, it is not at all clear that high levels of REO turnover lead to stabilization—a high volume of investor purchases in an area is not likely to achieve stabilization without other support mechanisms in place. In this particular case, the REO-to-rental initiative, this could actually work against the goal of stabilization because there is no clear community development strategy outlined in the initiative. What will happen to these properties and the community itself when the term expires? While some argue that an investor purchase is better than the house sitting vacant, this does not mean that we should embrace such a transaction without measures to help protect the surrounding community, and this should happen at the federal level— providing support and guidance for local enforcement of these properties—as well as at the local level; for example, establishing federal incentives for responsible ownership, tracking the maintenance or impacts of properties, or establishing local ordinances, inspections, and the like.

And finally, turning over pools of REOs to investors continues the trend of disconnecting local housing—and local communities—from local control. We tried this experiment when we allowed—even encouraged—the connection between homeowners and their local banks to be broken, and instead encouraged numerous and flawed global financial products, and institutions to take control. With these private investors looking to expand their portfolios of REOs from all over the country, we again run the risk of further destabilizing these communities, the exact opposite of what proponents of the program suggest.

The widespread foreclosure crisis, though devastating, represents a unique opportunity for advancing fair housing in high opportunity communities, an opportunity that the REO Initiative must take advantage of. The government has a legal obligation to meet this opportunity through the Fair Housing Act. Because the crisis has also hit higher opportunity, middle class suburbs, connecting these dots is not only the fair strategy, but a logical one. At the same time, the government must also ensure that the REOs-turned-rentals in more distressed communities do in fact stabilize these communities, and support the ongoing and much-needed work of community revitalization in these areas.

Comments