Before the emergence of state housing finance agencies (HFAs) in the 1960s, the federal government and local public housing authorities were where affordable housing development and finance began and ended. Beginning with New York, HFAs represented the first coordinated state government response to the failure of the private market to provide low- and moderate-income housing. They were born on the heels of the civil -rights movement and urban riots, and amidst the deliberations of the Douglas and Kaiser Commissions on urban problems and housing. These two landmark presidential commissions identified the lack of affordable housing, coupled with intense residential segregation, as major contributors to the frustration and anger of communities of color. Those states with cities that had some of the most violent and costly riots — Detroit, Mich.; Chicago, Ill.; and Newark, N.J. — were among the first to establish housing finance agencies. HFAs emerged as both a practical and politically expedient means of increasing the supply and affordability of housing at little cost to the state. They were used to finance housing construction and purchase through the sale of bonds and to administer emerging federal programs, such as the Section 236 mortgage-subsidy program for multifamily housing construction. By doing so, these agencies became a revenue-generating, financially self-sufficient means of increasing affordable housing. The strategy yielded dramatic results. In 1973, the 12 most active HFAs reported financing more than 200,000 affordable units through bond sales, the federal Section 236 program, and other sources. Over the years, HFA activities have evolved significantly, from an experiment in affordable-housing finance to the primary mechanism for addressing state-level affordable-housing needs. A thorough understanding of HFAs is thus crucial for those seeking to expand access to housing for low- and moderate-income households. Nevertheless, most housing advocates have an imperfect grasp of what HFAs do and how they can effectively influence HFA actions. Advocates often underestimate the scope and power of HFAs, and overestimate the complexities of housing finance, especially bond financing. They also find themselves at a strategic disadvantage because of a lack of comprehensive public accountability for HFA programming.

HFAs in Action

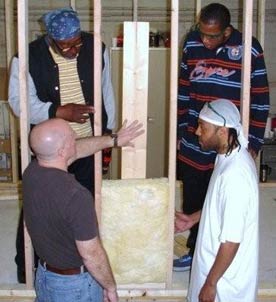

Beginning in the 1980s, HFAs grew in their role as administrators of various federal and state subsidy and finance programs, including the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, and a variety of state programs, such as housing trust funds and tax credits. Today, through their mortgage revenue bond programs, HFAs finance more than 100,000 new low- and moderate-income homeowners every year, and have assisted more than 2.2 million households to date. In addition, they have financed more than 1.3 million rental units nationwide through the use of the LIHTC program. In addition to these traditional financing activities, HFAs are increasingly involved in other housing arenas. More HFAs find themselves in the position of planning and coordinating multiple housing programs, either because of specific legislative or gubernatorial mandates, or an existing leadership vacuum that agencies choose to fill. This includes developing the Qualified Allocation Plan for the LIHTC program, as well as contributing to HUD-required consolidated plans for the use of federal Community Development Block Grant (CDBG), HOME Investment Partnerships (HOME), Emergency Shelter Grant (ESG), and Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS (HOPWA) programs. Some states, such as Illinois, require HFA participation in an annual comprehensive plan for addressing critical housing needs, with a requisite action plan and annual progress updates. Many HFAs also recognized the importance of increasing the ability of nonprofits to develop and manage affordable housing. They often support this by funding technical-assistance providers and training programs focused on improving these skills among nonprofit developers.

HFA Priorities

There are at least four defining characteristics of state housing finance agencies that influence their activities. First, as lending institutions responsible to their board of directors, bondholders, and the agencies that rate their creditworthiness, they are financially risk-averse. Second, as production-oriented financers of affordable housing, they are beholden to the developers and financial institutions with whom they partner. Third, as quasi-governmental agencies, they are politically engaged, guided by the actions of the governor and legislature. Finally, as agencies with a public mandate to address state low- and moderate-income housing development, HFAs are socially mission-driven and thus accountable to housing consumers and their advocates.

It was exciting to read Prof. Scally’s balanced and informative article about Housing Finance Agencies, which are often a mystery to housing advocates and other housing-related nonprofits. We are fortunate in VT to have a progressive HFA that got the state’s multi-interest housing campaign off the ground in partnership with many other state housing agencies and affordable housing coalition members. The VT HFA also reached out to form a partnership with NeighborWorks America when five VT nonprofits were chartered by NWA, and have invested considerably in VT’s NeighborWorks network in order to enhance successful homeownership and mortgage borrowing among HFA and other homebuyers. It takes a lot of creativity on the part of an HFA director, and flexibility within the affordable housing community to leverage HFAs’ resources, but the opportunities are extensive and Scally shines a nice light on the possibilities.