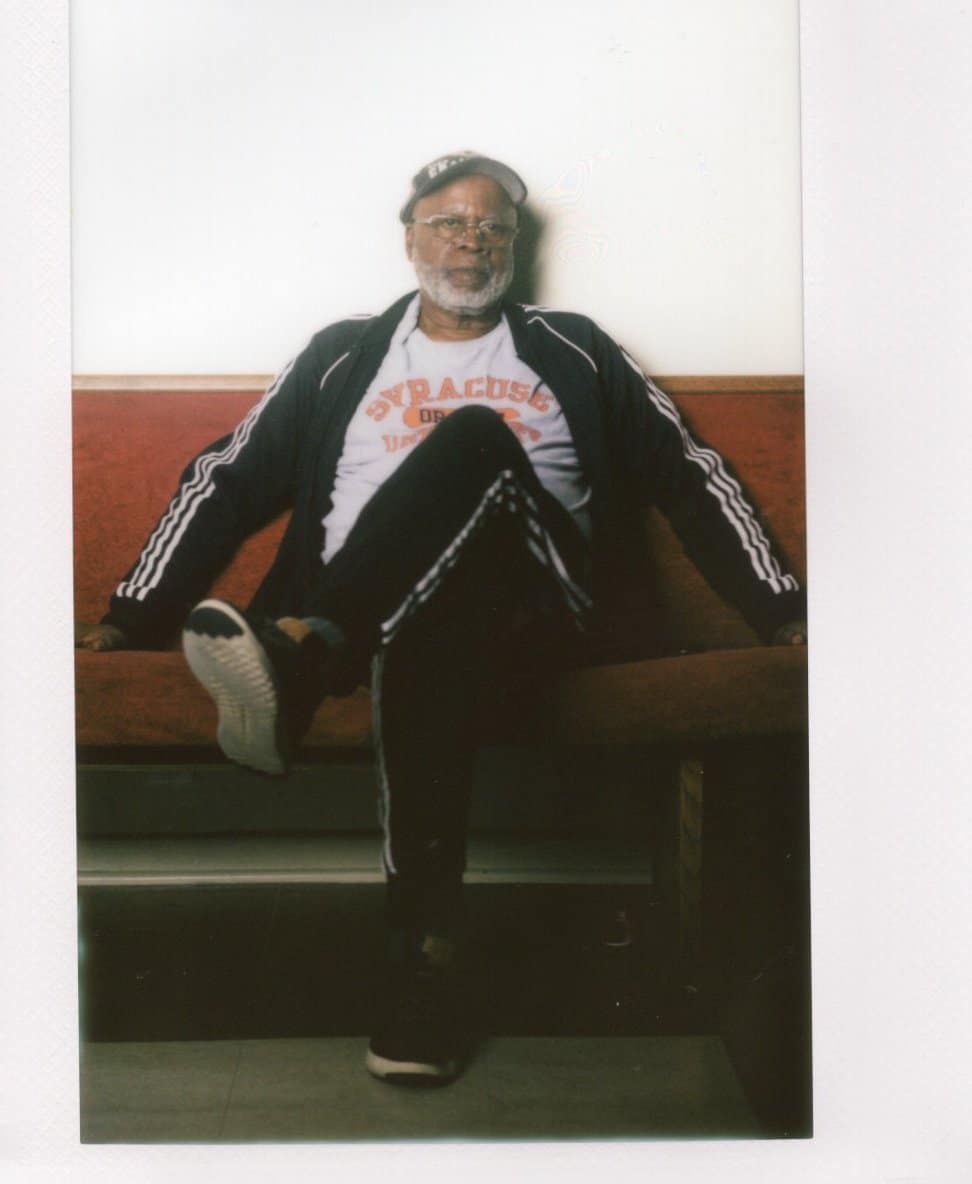

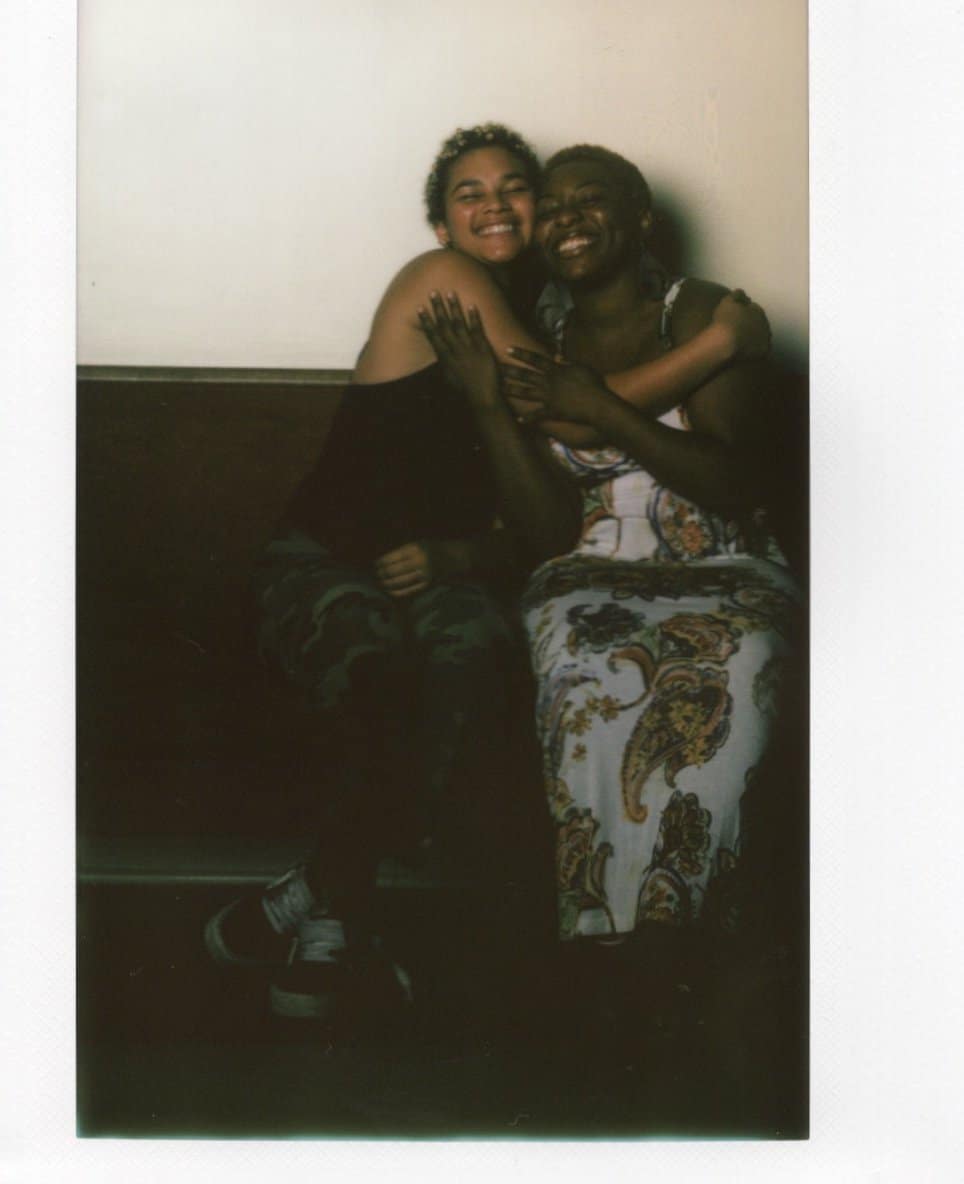

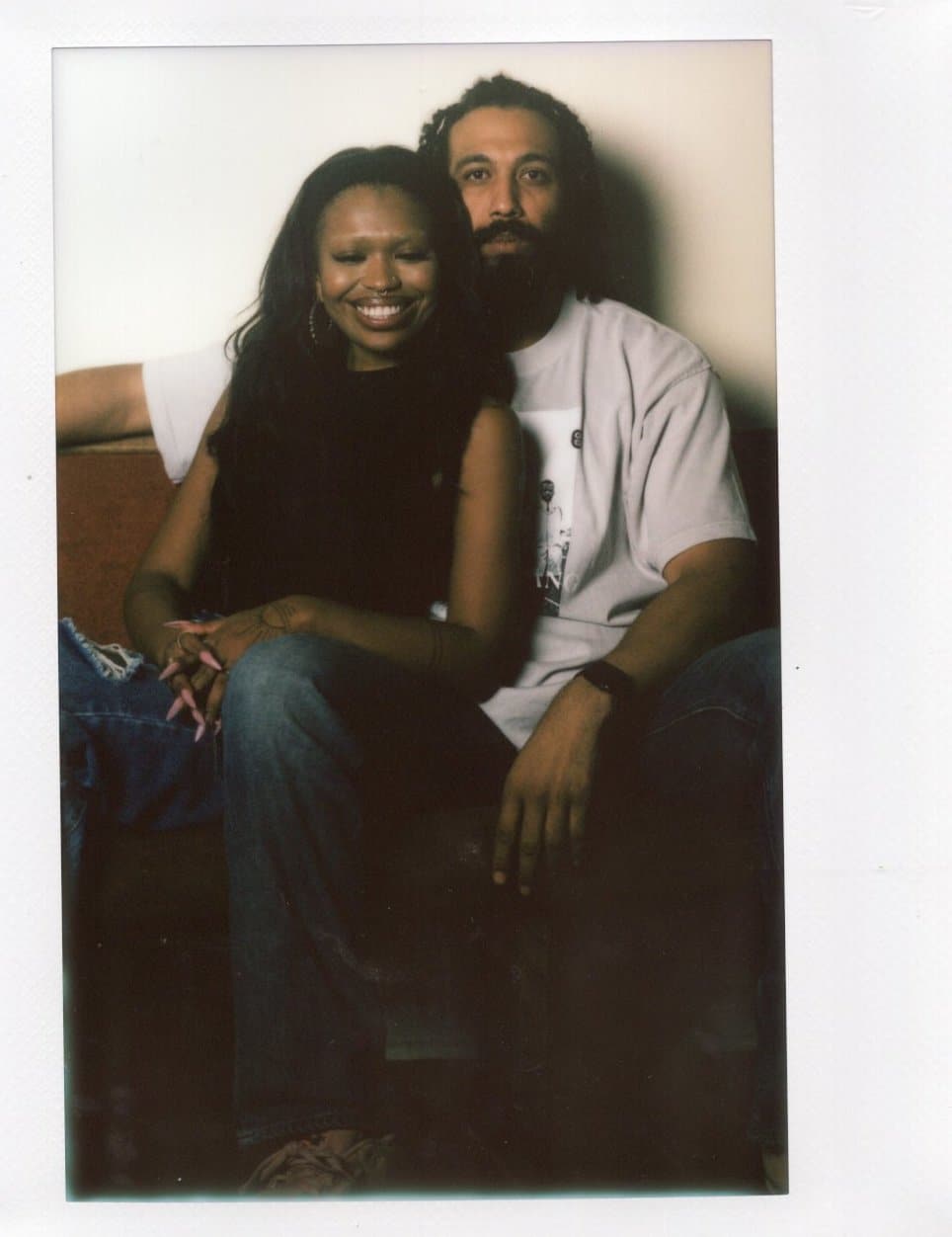

Artist Autumn Breon hosted an event where residents took family portraits and shared photos and memories about Black Santa Monica. Polaroids by McKayla Chandler Autumn Breon is a Los Angeles-based multimedia artist. In October 2024, Breon hosted an event at the Calvary Baptist Church in Santa Monica: the Ebony Beach Club Memory Portal. The church is just two miles from the Viceroy Hotel, the site where the Ebony Beach Club once stood, a Black leisure space owned by Silas White that was set to open in the 1950s. But before it could open its doors, the city used eminent domain to seize the land to use as a parking lot.

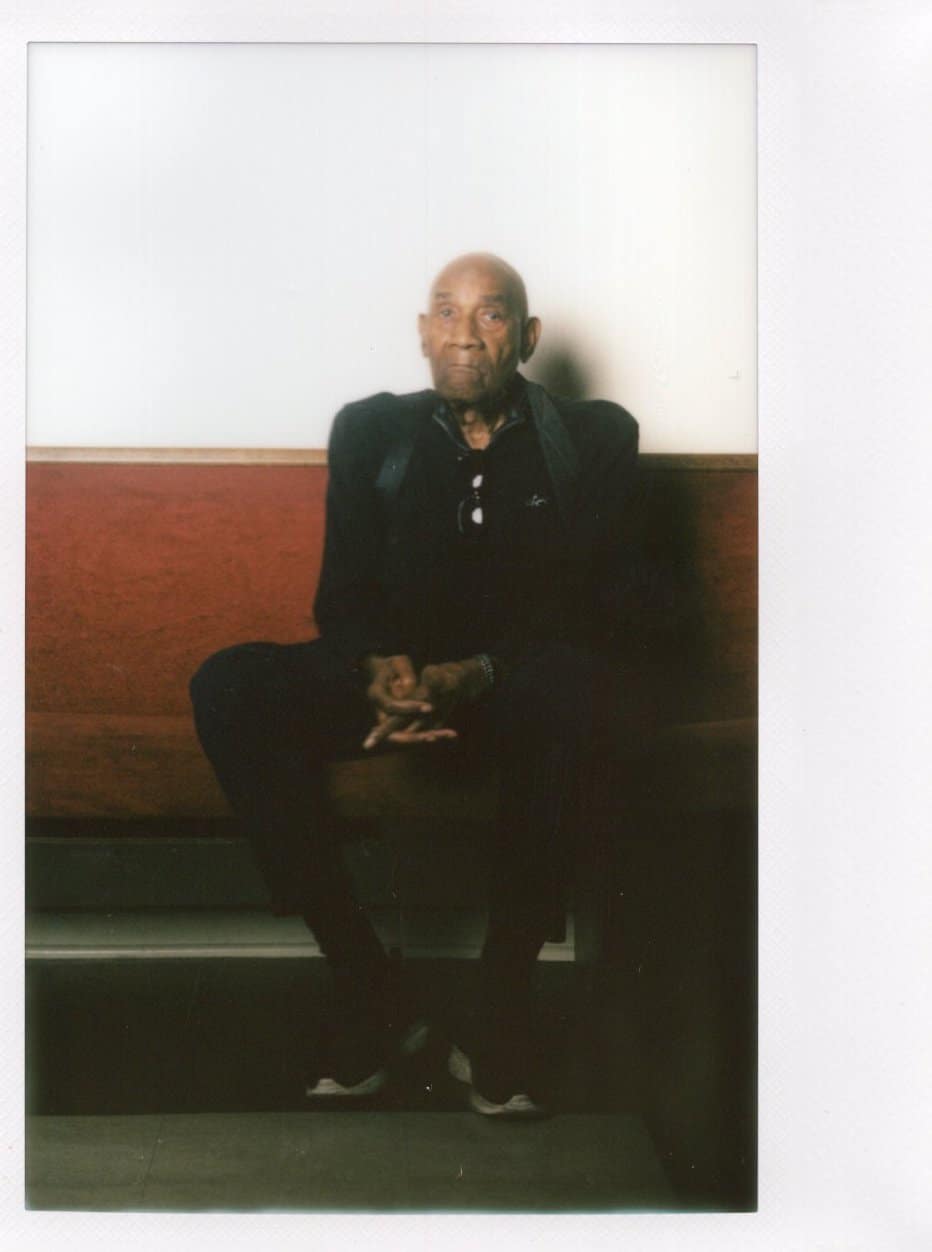

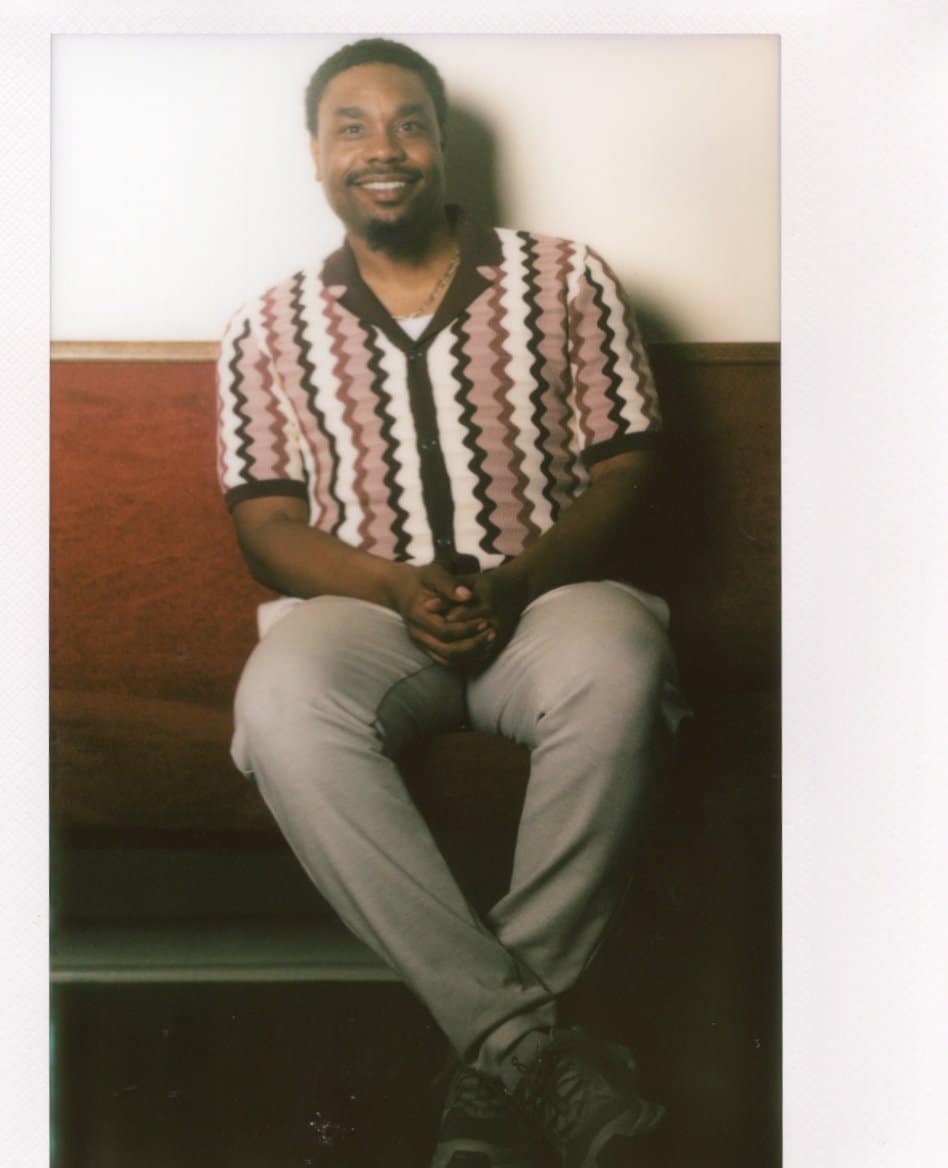

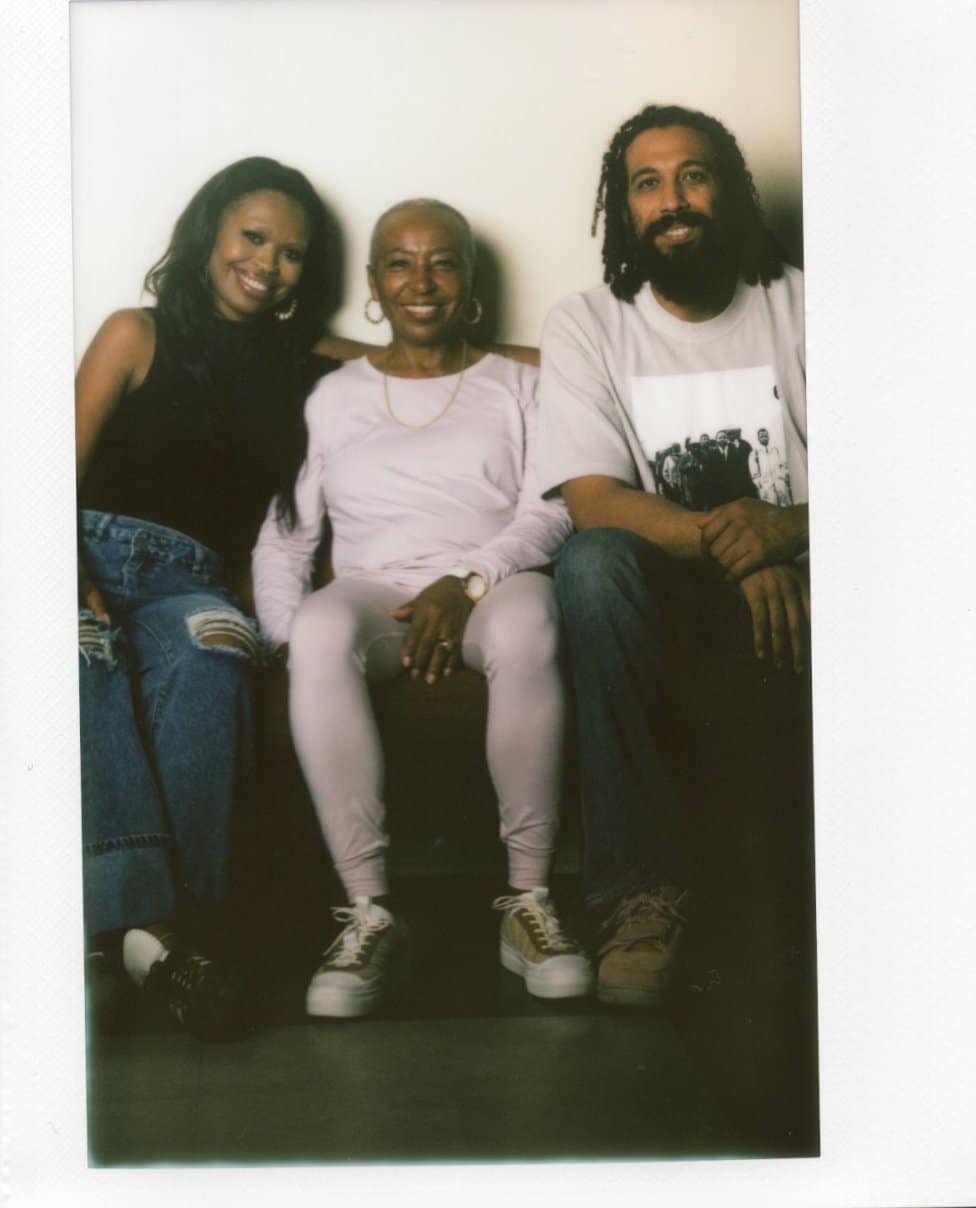

Residents of all ages gathered to participate in a group cypher. They also shared their memories of the city, brought old family photos to digitize, and took family portraits on-site. The event opened a space for residents to share and archive their memories of the city. Among the participants were Connie White, Silas White’s daughter. White’s family is seeking restitution from the city.

I recently spoke with Breon about how the story inspired her multidisciplinary art event and her interest in the history of Black leisure sites. Below is an excerpt of our conversation.

Lara Heard: Can you tell me about the Ebony Beach Club Memory Portal, what that project is, how you got it started, and such?

Autumn Breon: Yes. It was really great with the support of Americans for the Arts and Race Forward to be able to participate in the Cultural Week of Action around this project, the Ebony Beach Club Memory Portal. It was basically a storytelling cypher. A lot of my work is related to intuition, memories that we have, memories that elders and ancestors might carry, and how we can use information like that to figure out the systems that we’ll make for the future. I really wanted to use that approach with continuing to tell the story of Ebony Beach Club.

Silas White purchased this land in Santa Monica and planned on building Ebony Beach Club. It was meant to be a place with live music, jazz, access to the beach, really just a place for leisure for Black folks in Santa Monica, because there weren’t safe places that provided that for Black people in Southern California at the time. He acquires the land, started getting [people] to sign up to be charter members of Ebony Beach Club, and Nat King Cole was one of those members. It was something that was talked about in the community; people were looking forward to when it was going to open. The city of Santa Monica used eminent domain to seize that land and said that they needed to build a parking lot for the city. So Ebony Beach Club never opened. The parking lot wasn’t built. The Viceroy Hotel was built instead, and it still exists to this day. When I learned about that story, I immediately wondered, “Well, what would Ebony Beach Club be like if it still existed now? If this was a social club that had existed for decades?”

Silas White’s … daughter, Miss Connie White, is still alive. His grandniece, there are descendants that are still alive. They shared their memories of what Ebony Beach Club was meant to be, what Santa Monica was like, at this Ebony Beach Club Memory Portal. Other folks in Santa Monica, people in LA, all gathered to share their stories and memories of Santa Monica, as a celebration of storytelling, really.

Can you talk a little bit more about the format of the event? Because I know you had folks bringing in family photos. You had some poetry, I think, also being read at the event.

Something that was so special about this was how collaborative it was. The kind of collaboration that exists with people being vulnerable and sharing their stories in a cypher like that, but also the organizations that supported and collaborated to make this happen. Where Is My Land, obviously, which works to return land in situations like this that have happened throughout the country for a long time, returning land to descendants. Black Image Center, which is a really great group in Los Angeles. That’s who we worked with for the photo digitization that you were mentioning. They had some of their folks there. It was so generous of them. People could bring a photograph and it was digitized for free so that folks could have their hard copy, obviously, but a digital copy. And also just to make it clear and create the invitation for archiving, for us being able to archive at home. So many times folks will think that an object is important once it’s in a gallery or a museum. I don’t believe that. I believe that the personal archives that we hold have so much information and so much beauty. Sometimes we just have to be reminded and have the tools and resources to be able to preserve some of those images and memories.

So many times folks will think that an object is important once it’s in a gallery or a museum. I don’t believe that. I believe that the personal archives that we hold have so much information and so much beauty.

Yes, people were invited to come, bring a photograph of any kind of memory that would be digitized, and then use that photo as an anchor for the story that they shared in the cypher.

Somebody was playing the piano at one point. There was a young person there that was sketching folks as they came up to speak and share their memories.

Then some folks were just inspired to share a story once they were there and heard other people’s memories and stories of Santa Monica. Kavon Ward, the founder of Where is My Land, did a poem at this cypher. It was completely multidisciplinary, collaborative, a really special afternoon at Calvary Baptist Church, which is one of the oldest Black churches in Santa Monica.

When you say a cypher, can you describe what you mean by that?

A cypher, that’s a nod to the history of hip-hop. These cyphers that existed where there would be freestyling, beatboxing, breakdancing, graffiti, all of these elements of hip-hop in one place at the same time where people were—like a call-and-response of art that’s oral and movement-based. It was a nod to that call-and-response–informed circle for sharing stories when the spirit moves you or if you have a spirit that moves you through photographs, through memories.

Did you have any sort of response from the city or from any dialogue with folks in Santa Monica about what this meant, and reflections on the past because of it?

Something that was really important to me when thinking about what this day would be like—and I was so glad that it worked out like this—there were so many generations that were there. I think the youngest person was probably 3, and the oldest person 103, 104. And active telling stories or kids running around, you could hear them. We also had free family photos… They could sit for a portrait and you got an image that you could take home with you to chosen family, your biological family, whatever.

What I thought was so powerful was hearing directly from people that have been in Santa Monica for generations and also folks that have moved to Los Angeles and Santa Monica. Some folks were just hearing about this history for the first time. It was powerful to be able to hear folks that were grateful to be able to share these stories out loud, share these memories of what they remembered for what Santa Monica was like and what they want it to be.

For other folks that might be new, still felt safe enough to ask questions about what happened and to find out how they can be involved to support the family that’s seeking restitution now. I think that’s really important, having folks that are indigenous to the city and also folks that come from multiple generations.

Were there any speakers that stood out to you or that made an impression?

A couple. Miss Connie, Silas White’s daughter, came up to speak. She’s in her 90s. To hear her remember being a child in Santa Monica and all of the dreams and hope and fortitude that her father had—to be so innovative, come up with an idea like this, to meet a need, and to do everything that you’re supposed to do. Santa Monica was his home and he did everything that he was supposed to do in order to create, again, this safe place, this safe haven.

Knowing that she saw all of this happen as a child and is actively a part of this fight to have everything that her father fought for, it was chilling to just hear—the same fortitude that I imagined Silas White had, I could see that in her when she was just telling the truth. It was really, really beautiful, very candid. I thought really grounding for why we were there.

It was also touching to hear two folks in particular that talked about their journeys to Los Angeles from the South and from the Bay Area and how they ended up relocating and LA is their home now.

They were talking about their idea of Santa Monica and how they had to work so hard in order to find out that this history had happened in a place that they come to so frequently. They talked about taking their daughters to the beach at Santa Monica and going to the pier and riding bikes by the sand, but finding out that this place that has a beautiful facade has a really dark and recent history. I loved that in their storytelling, they framed, basically saying if Ebony Beach Club was still here, what would my daughters get to experience in Santa Monica?

That’s what made Ebony Beach Club, its memory, and the potential future for the descendants and for the family, that’s what made it so personal for them. I thought it was just really great to see the spirit of Ebony Beach Club bridge so many generations and demographics and for us to be able to hear that through storytelling.

I grew up in California as well. I feel like sometimes we forget how much history California has, just because people think of it as shiny and new. People have been here for generations and there’s plenty that happens that we don’t learn about in school.

Which is why places like the Ebony Beach Club Memory Portal, I think it’s so important for that to be recreated so that we aren’t only relying on one source for us to know what actually happened. Yes, our education system should be a lot better. We should know this. It’s something that we should learn. But it’s not there yet. We have to create examples of what it actually looks like to have sources of accurate information for each other. Because I believe that’s a form of care. I thought that the environment was really an environment full of care because multiple people had their needs met, they felt safe enough to share their stories. I think there’s so much care in hearing what actually happened and being able to continue the dissemination of accurate information. That was really important for how the day was designed.

Are there any projects you’re working on now that you wanted to share?

I’m working on a project . . . the sculpture that was shown in St. Louis during Race Forward’s Facing Race conference that was also a big part of my . . . [Housing, Land, and Justice Artist Fellowship]. My research was the same in this fellowship. I used audio from the storytelling cypher to be a part of this sculpture, which is a directional sign.

The signs all point to and have the names of Black leisure sites that used to exist or that still exist in California. Also, some fictional leisure sites that I think are still significant. I like to mix together reality and fiction. The names of the places are the Salton Sea, Ebony Beach Club, Bruce’s Beach. Acorn from Parable of the Sower is also one of the places on the sign because I think Lauren Olamina created a leisure site. I think that was also a community that’s just as important as these other ones in California. I used wood and I painted it all blue. The letters are white on top of the sign and there are keys that hang from each arrow. That’s just a reminder of the fact that these are not only geographic locations, but places where people had homes and families and keys, supposedly. I have different shapes of keys that are all golden and also different ages. Some of them look a little bit more tarnished. That’s another visual timeline for how long this has been a problem.

It’s basically meant to be a directional sign with roots at the bottom. It’s like a tree that has long roots and ones that are resistant as a reminder that these individual places are connected. These people’s stories are connected and it’s a hard tree to knock over. It might be a long fight, but there’s strong roots. The audio that was playing was people’s memories of these different sites. There’s a phone that folks could pick up and [hear] people’s memories of the different places that are on the sign.

Is there a time when you first got interested in these spots of leisure and this history that people don’t necessarily know as much about? Was it from the Ebony Beach Club specifically or before that?

Before that. My grandparents migrated to LA in the early 1950s from Alabama and they would always go fishing at the Salton Sea. There were so many other Black families and then eventually their kids and grandkids that would also go fishing there. It was just something that was a part of my day-to-day life. I knew on a Friday, Granddaddy’s probably going to drive out to the Salton Sea, come back on Sunday with some fish, and I would go with him sometimes. As I got older, I started to find out that there were people even in LA that had never heard of the Salton Sea and didn’t know that there was this Black fishing community out in the desert.

Folks are familiar with Indio and Coachella Valley, but didn’t know about this community of Black folks that were going out there fishing. That’s when I was first familiar with some of these histories of leisure sites. I think I started to develop the vocabulary for it and really learn about folks that were researching and organizing around these sites. [It] was probably in 2020 when I first learned about Bruce’s Beach in an LA Times article.

Due to several serendipitous circumstances, that’s when I was actually connected with Where is My Land and with Kavon Ward and just asked, ”What kind of support do you need for trying to return this land to this family’s descendants?” Because I just thought it could set such an incredible precedent for there to be an example of something like that. That was when Kavon said, ”Could you make some art that tells the story of what happened because so many people don’t even know about Bruce’s Beach? Folks that are in Manhattan Beach in LA.”

I started to explore performance as a way to shed light on forgotten histories. I think that’s what really put me in that direction. That inciting incident, Kavon’s work, and a place that was a physical place, Bruce’s Beach, that’s so close to where I grew up. That’s when I started doing that kind of research and then making art from that research.

Has the increase in wildfires in California made you think any more about place and community impermanence? For a lot of folks, it’s reminding them that things that have been around for decades might not be around anymore.

Yes. In the blink of an eye, how rapidly a reality can change is what one of the biggest reminders has been for me since these fires. Also, how there’s so many truths that folks have been expressing and demanding for folks to listen to for so long. This isn’t a new problem. We have the Santa Ana winds every year, and there are a lot of environmental issues and climate crisis issues that a lot of organizers, mobilizers, scientists have called out for so long, and we’re also seeing the repercussions of those very quickly and the impact that that has on real people.

I also think of Altadena, another place that just has such a rich history. So many Black families that again, created a safe community for themselves when it was hard to find and create that anywhere else. To see so much of that legacy in flames is scary and it’s very sad.

The hope that I have to believe in is that we’ve not only survived but thrived before, so it has to happen again. We are capable and have the ingredients for place-making that were a big part of the Ebony Beach Club Memory Portal. This is how we archive on our own. These are ways that oral histories can be preserved. This is how we prioritize and center these stories. Those are some of the things that I think we have to actively recreate, focus on, right now.

Comments