This article is part of the Under the Lens series

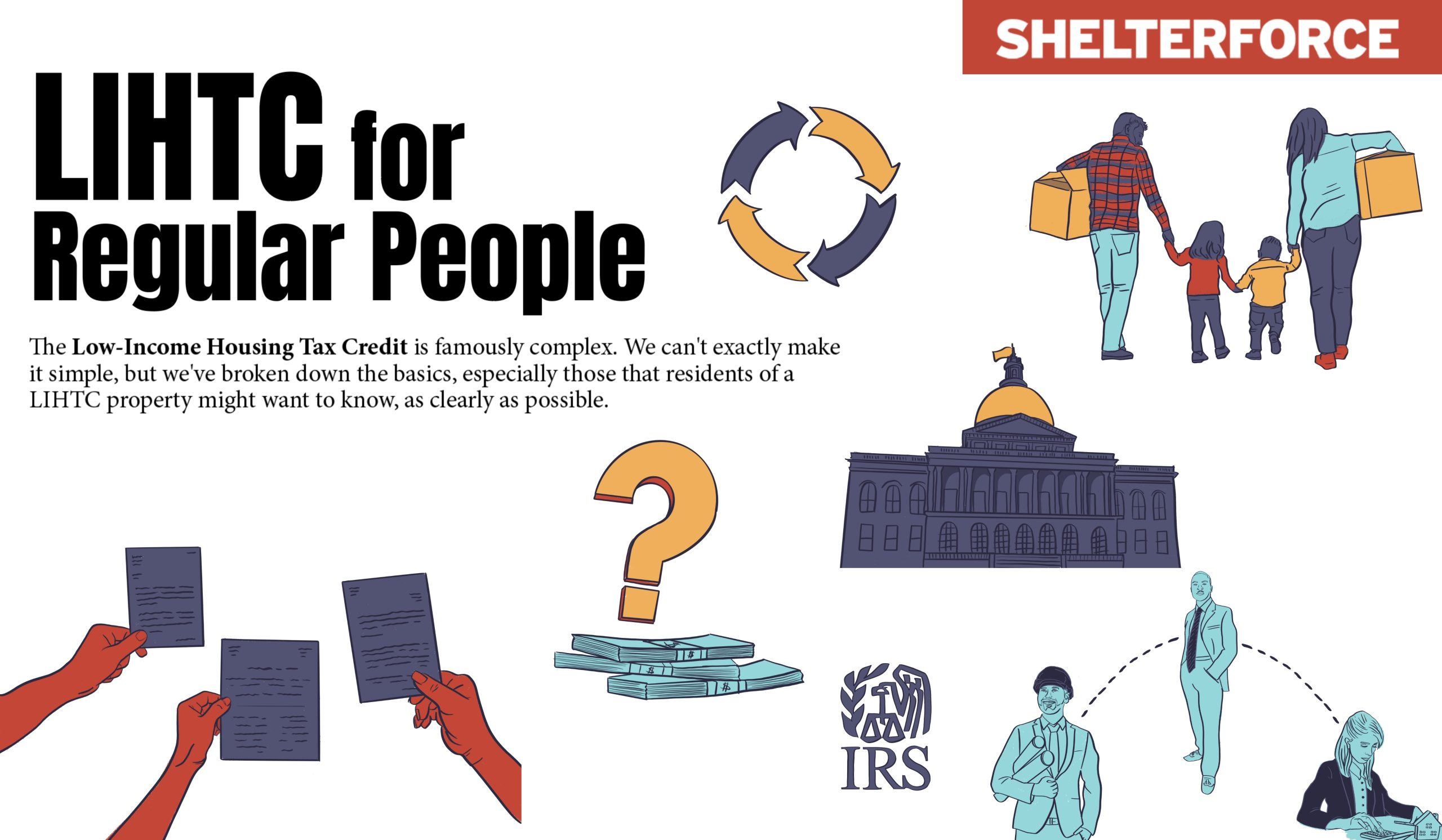

LIHTC: The Good, the Bad, and the Very Complicated

Photo by DNY59 via iStock

Last year, Shelterforce wrote about two affordable housing developments in Northern Virginia where tenants awoke to find their rent had suddenly been hiked. Although tenants across the country were facing rising rents, alongside a tight housing market and some of the highest inflation rates since the 1970s, these rent hikes were different. They occurred in the middle of leases, at housing funded by the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC).

Since our coverage, those tenants say that management kept its promise to stop its sudden rent hikes and only increase rents once, this past July. But this commitment wasn’t written into any lease agreement, and management didn’t make any promises not to hike rent in the middle of leases in future years. No laws have been passed at the local or state level to prevent mid-lease increases at LIHTC developments in Northern Virginia.

That’s not the case everywhere, however—Georgia, Minnesota, Texas, and Washington have all passed laws in recent years banning mid-lease or mid-year rent increases in affordable housing.

When we checked in last year, management of Fields at Cascades, one of the Northern Virginia LIHTC-funded developments, met with tenants. They agreed to only raise rents once a year in July, with no hikes at the end of leases. That agreement only stood for one year, however.

“They have stuck to that, but they did increase the rent by 7 percent in July again, which is a couple hundred dollars,” says Sofia Saiyed, an organizer with New Virginia Majority, a statewide nonprofit that works for racial, economic, and environmental justice. “The rent increases aren’t stopping and it’s increasingly hard on tenants.”

Without legal protection, mid-lease rent hikes at developments like this one can happen whenever HUD increases income limits.

Here’s a look at states where those protections do exist.

Existing Protections

In 2020, Minnesota banned mid-year rent increases in buildings that received certain government subsidies.

Prior to that, Minnesota had allowed LIHTC landlords to include provisions in lease agreements that granted them the right to raise rents at any point in response to changes in area median income (AMI). Sometimes tenants’ rents were increased immediately after they signed leases, before they moved into their new homes, says Margaret Kaplan, president of the Housing Justice Center (HJC), a nonprofit housing advocacy and legal organization. Kaplan says that many of these tenants decided to sign their leases based on the rents that were advertised to them. They were trapped paying rents they hadn’t agreed to.

These occurrences spurred HJC tenant activists to take action alongside HOME Line, a nonprofit that provides legal services related to housing. HOME Line had already been organizing tenants and hearing about these mid-lease rent increases when HJC approached them. The activists considered their options and decided that their best approach would be to engage Minnesota’s housing finance agency, known as Minnesota Housing.

Kaplan says that the organizers saw this as an opportunity not just to ensure that future LIHTC developments were barred from using mid-year rent increases, but to ban the practice in existing LIHTC developments as well.

“There were so many tenants who were being affected by this, who were organized and who were contacting the agency and policymakers, that the agency was really compelled to do something about it,” says Kaplan.

In most states, housing finance agencies oversee the implementation of the federal LIHTC program. Every LIHTC property in the state must commit to follow the rules that the agency documents in the state’s tax credit compliance manual, including any changes made to the document.

Minnesota Housing adopted and approved a change to the manual that effectively forbid LIHTC owners to increase rents in the middle of leases.

Kaplan says that organizers chose to go through the housing finance agency instead of passing legislation for two reasons. First, writing up a bill and getting the state legislature to approve it would likely take much longer. Second, the LIHTC program is complicated.

“I think it’s difficult to explain to people what the issue is and why it’s important, and so you have to do a lot of education of policymakers in order to really get that traction,” Kaplan says. “Creating a strong partnership with your housing finance agency and then having a connection between people who are living in these properties and the people administering and regulating the program does give a real opportunity to make some changes.”

Minnesota isn’t the only state that has banned mid-lease and mid-year rent increases in LIHTC properties. In 2019, Washington state added a requirement in its LIHTC compliance manual that building owners wait until the end of the lease term to raise rents. In 2020, Georgia followed suit, banning owners from raising rents more than once every recertification period. The state also requires that any rent increase larger than 5 percent comes with a 120-day notice with an option for the tenant to terminate the lease without penalty. That same year, Texas enshrined a ban on mid-year rent increases at LIHTC developments in state administrative code.

However, banning mid-lease and mid-year rent increases this way is not a silver bullet. Marcos Segura, a lawyer at the National Housing Law Project, cautions that a compliance manual in many states represents only guidance on existing federal and state LIHTC rules. “Unless the QAP or regulatory agreement expressly make compliance manual provisions binding on an owner, the binding effect of compliance manual provisions is debatable,” he says. “However, even in such cases, compliance manuals can serve as a key strategy in achieving greater tenant protections, since the document is generally followed by owners.”

Enforcement

Kaplan says that while Minnesota’s ban has been effective, enforcement could be better. “We were, even a year later, running into issues where somebody would get a notice of mid-lease rent increase, or something would exist in a lease agreement then saying that [the landlord had] a right to a mid-lease rent increase, and there weren’t necessarily mechanisms in place for the agency to track and monitor that.” In those instances, HJC would send a letter from a lawyer to the landlord, who would usually back down.

Segura also says that there have been several instances of mid-lease rent hikes in Georgia, despite the bans that have been included in the LIHTC compliance manual.

Without state-level action to prevent it, future increases in inflation could raise AMI. LIHTC tenants across the country may once again wake up to find their rents have been hiked, in the middle of their leases.

|

Now through Dec. 31, all donations to Shelterforce will be matched. Double the impact of your donation by supporting our work today. |

Comments