This article is part of the Under the Lens series

LIHTC: The Good, the Bad, and the Very Complicated

There’s not much wrong, strictly speaking, with the proposed changes to the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program described in Sandra Larson’s excellent Nov. 21 article. They are not, however, “reforms” by any reasonable definition, nor would they make much difference to the lives of most people who live in LIHTC housing or need affordable housing. The so-called reforms in the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act, the central piece of legislation featured in the article, fall into two categories: putting more money into the LIHTC pot and technical changes designed to make it easier to make LIHTC deals work. As Marcos Segura of the National Housing Law Project says in the article, “it’s just more of the same.” That is hardly surprising, because the impetus for the changes comes from what one might call the Tax Credit Industrial Complex, a network of for-profit and nonprofit developers, investors, syndicators, and others for whom the LIHTC is a multibillion-dollar industry. That it will benefit lower-income households is a consideration—many, probably most, members of the complex do care about that—but a secondary one.

LIHTC is not only the most important source of new affordable housing in the United States, it is in most places the only source. It is worth expanding, to be sure, as well as reducing opportunities for exploitation by bad actors, increasing equity in distribution, and fixing technical problems that make it harder to use. But it is more important to look at how it might be improved not from the perspective of developers and investors, but from that of the families who need better and more affordable housing and the communities where they live. That perspective suggests that there are some real reforms that ought to be put on the table. I’d like to suggest what three of them should be.

- Break out of the project trap and address the existing housing stock

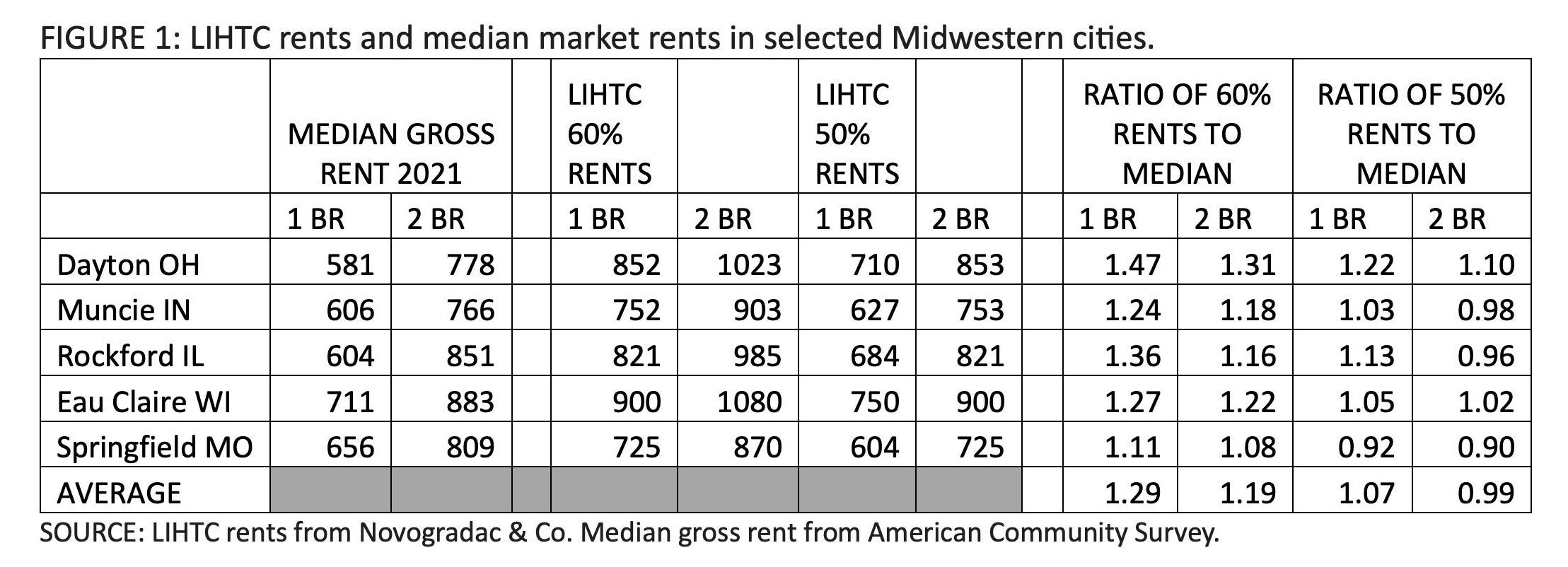

I am hardly the first person to point out that allowable LIHTC rents are comparable to or higher than median private-market rents in many parts of the United States. The 60 percent LIHTC rent for a one-bedroom unit in Dayton, Ohio, for example, is 50 percent higher than the median gross rent for such a unit in that city. Examples for five Midwestern cities are shown in Figure 1.

Why does this matter? Families opt for these units over similarly or lower priced units in the private market because they are bright and new, offer more facilities such as off-street parking and on-site laundry rooms, and in many cases—particularly in large projects—offer a greater sense of security than smaller private rental properties. Many families have or get project- or tenant-based vouchers to help them afford the higher rents they have to pay.

I can’t blame them. But how does that affect the local housing market, and the neighborhood?

Most of the projects are in high-poverty neighborhoods where housing demand is more often declining than growing, and which usually have high vacancy rates. By adding new housing at higher but accessible rents (partly thanks to vouchers), the LIHTC projects are cannibalizing the neighborhood market. Rather than improving the neighborhood as a

whole, they are as likely to contribute to neighborhood decline and the loss of still-salvageable older housing units. The program adds thousands of units in neighborhoods that would not need more housing, if only the existing housing in those neighborhoods could be upgraded to meet the needs of residents. The problem with that, under current conditions, is that it is expensive (although far less than building a new LIHTC unit), and can’t happen without the landlord either increasing the rent or going bankrupt.

A real reform of the LIHTC program would provide an alternative way of using tax credit proceeds to solve that problem. One workable approach would be to allow (or require) state allocating agencies in states like Ohio and Michigan—where this problem is widespread—to allocate all or part of their tax credits to investors willing to put their money into a housing rehab fund rather than into new or gut rehab LIHTC projects. Once assembled, money from the fund would be used by the state to provide grants to small landlords of habitable single-family houses or small multifamily buildings needing upgrading in lower-income neighborhoods to repair and upgrade their properties. These grants would be provided either directly or through intermediaries like local governments, land banks, or high-capacity CDCs, would require a minimum of bureaucracy, and would not involve any change in ownership of the properties.

Since the cost of upgrading such properties is likely to run between $30,000 and $50,000 per unit, the results would be that 6 to 10 existing privately owned units would become high-quality affordable rental housing for every one new LIHTC unit forgone. In return, the landlord would have to agree to maintain the rents at or below LIHTC maximum rents for at least 15 years (or perhaps 30 depending on the nature of the assistance) and agree—in those states where it’s not required by law already—to take tenants with vouchers.

Alternatively, as suggested by Kirk McClure, professor emeritus of urban planning in the School of Public Affairs and Administration at the University of Kansas—and probably the most prominent independent expert on the LIHTC program—the allocation could be turned into vouchers. This is a reasonable idea, which addresses the affordability problem head-on, but may be less desirable, for two reasons: (1) it does much less to improve the quality of the stock available to lower income families; and (2) once you fund a family with a voucher, you have to continue to fund them; thus, this use of the allocation would have to continue indefinitely, reducing future flexibility in use of the state’s LIHTC allocation.

One ancillary benefit of either of these models, although not necessarily appealing to members of the Complex, is that they eliminate all the costs associated with packaging, syndication, and the like, although slightly reducing the proceeds, since investors will no longer be able to add the (modest) value of depreciation to the value of the tax credit as such, nor will they have the possibility of recouping the initial investment. Other than modest administrative fees for the agencies that manage the grant program, though, every dollar of the tax credit proceeds would go directly into improving housing for low income renters.

2. Better meet the needs of those who need housing the most

Looking at who actually lives in LIHTC housing is a bit of an eye-opener: it’s not the people for whom it was designed to be affordable. People who actually manage LIHTC housing know this well, but it hasn’t been widely discussed in the affordable housing universe. A few key points:

- Over half of all LIHTC tenants have incomes below 30 percent of HUD-defined area median income (AMI), with another 16 percent between 30 and 40 percent of AMI. With the exception of Florida, this is pretty consistent from state to state.

- Less than one quarter have incomes between 40 and 60 percent of AMI, the theoretical target population for LIHTC housing.

Since LIHTC rents are set to be affordable at either 50 percent or 60 percent of AMI, how do the residents making less than that manage to afford them?

- Perhaps as many as half of all LIHTC tenants (it’s hard to be precise because of the way the data is reported by HUD) receive rental assistance, either project-based (which can be combined with LIHTC) or tenant-based.

- Despite this, two out of five LIHTC tenants spend over 30 percent of their income for rent—in other words, they are rent burdened while in technically affordable housing. One out of eight spends over 50 percent of their income on rent.

Whatever its planners intended, the LIHTC program has become de facto a program for families earning 30 (or maybe 40) percent or less of AMI. This is not a bad thing in itself, because these are the people with the greatest needs. But it comes at two costs: it uses up a large part of the rental assistance that would otherwise be available for private-market housing and it perpetuates the housing cost burdens that afflict America’s low-income renters.

A case can be made that targeting rental assistance to LIHTC projects is cost-effective in high-cost areas like San Francisco or D.C., where LIHTC rents are lower than HUD fair market rents (FMRs). In San Francisco, where LIHTC 60 percent rents are around 84 percent of the FMR, a dollar of rental assistance should go farther in an LIHTC project than on the street. (Currently it doesn’t, because LIHTC projects can get the full voucher amount up to the FMR, even where the FMR is greater than the maximum LIHTC rent. One useful provision of the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act would be to cap rental assistance at the maximum LIHTC rent.) In Dayton, the opposite is true.

The Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act proposes a generous incentive to developers to include units targeted to households at 30 percent of AMI. For every unit so targeted, the developer would get a bonus of up to 50 percent of basis, meaning that the value of their credits goes up by 50 percent. This is wonderfully generous—one can be confident that developers would run their numbers to get the full 50 percent bonus or close to it for however many such units they want to include—but at a huge cost: it would reduce the total number of units that the state can fund.

In all but the most expensive markets, a LIHTC development that is layering state, local, and other federal money onto the tax credit investment proceeds should be able to target a significant share of families at 30 percent of AMI without any increase in subsidy. Rents for a two-bedroom unit in Baltimore that would be affordable at 30 percent of AMI, for example, are $821 per month, enough to cover operating costs and throw off a little for debt service. In other cases, it may require some increase in LIHTC subsidy, although not likely for projects developed in “qualified census tracts” (QCTs), a proxy for areas of concentrated poverty. Projects in QCTs already get a 30 percent increase (unless that boost is abolished, as I suggest below).

I don’t know that there is a simple fix for this problem (the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act provision is not one), but I can suggest how we should start thinking about it:

- Acknowledge that the LIHTC program is—and should be—a program that serves households at 30 percent of AMI, and stop pretending otherwise. That doesn’t mean LIHTC projects shouldn’t serve households at 40–60 percent of AMI, but recognize that they are not the primary target population for the program or the people with the greatest need.

- Establish the principle that at least 50 percent of all LIHTC units going forward should start off affordable (without vouchers) at 30 percent of AMI or the federal poverty level, whichever is greater.

- Restructure the calculations for how much LIHTC subsidy a given project can get (its “basis”) to reflect how that goal affects project feasibility, taking into account variation from one geographic area to another.

As a general proposition, it would be best to take this as an opportunity to both simplify the system and make it more sensitive to geographic variations in costs, incomes, and need, rather than layering another condition for a credit boost on top of an already complicated system.

3. Eliminate the qualified census tract bonus

The importance of seeing more LIHTC projects built in low-poverty areas, which are likely to be more job-rich and have better access to amenities, has been widely, but inadequately, addressed. Some states provide points in their qualified allocation plans for projects in areas of opportunity, but the majority of projects are still developed in concentrated poverty areas. A major barrier to changing this is the federal 30 percent bonus given for projects in qualified census tracts. Unsurprisingly, this is where the great majority of LIHTC projects end up. That increase is a powerful fiscal incentive to put them there. Those areas tend to be the homes of many of the CDCs that build LIHTC projects, usually have more inexpensive or vacant land than elsewhere, and rarely offer opposition to proposed projects.

Eliminating the QCT bonus is long overdue. There never was any compelling reason that development costs would be any higher in concentrated poverty areas than elsewhere. Moreover, with good evidence of the benefits of locating affordable housing in low-poverty, high-opportunity areas and for mixed-income development, no rationale exists for its continued existence. In theory, the “difficult development area” adjustment, which gives a bonus for projects in expensive areas, should balance it out, but the evidence of where projects go makes clear that it does not. Few LIHTC projects are developed in difficult development areas, except on those rare occasions when those tracts coincide with older, denser cities and towns.

The only justification for the QCT bonus would be if there were compelling evidence that the LIHTC program served as a significant engine of neighborhood revitalization, but the evidence of neighborhood impacts from LIHTC projects is at best mixed. One argument that I’ve heard from members of the Tax Credit Industrial Complex is that it fosters mixed-income communities by embedding people at 50 or 60 percent of AMI in neighborhoods where most people are at 40 percent of AMI or less. As the data I cited above makes clear, that argument does not hold water.

Time for Bold LIHTC Changes

These are almost certainly not the only issues that should be addressed. Many of the ideas Larson mentions are good ones. As Segura and others point out, tenants rights issues have long been ignored, and are overdue to be addressed. Loopholes undermining efforts to preserve long-term affordability of tax credit projects must be closed, while measures are needed to incentivize affordability beyond the 30-year horizon, up to and including permanent affordability. Greater transparency, monitoring, and accountability are needed. Most of the provisions of the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act, if not “reform” in any meaningful sense of the word, would be modest but sound improvements in the process.

The LIHTC, though, was created nearly 40 years ago as a part of omnibus tax reform legislation. It has morphed without conscious intent into not only a multibillion dollar industry, but the closest thing to a national affordable housing policy that exists today in this country. It was not designed to play that role, and while a valuable program in many respects, it does not play it well. The time is long overdue to recognize that reality, and to truly reform the program so it can provide greater benefits to more low income families, can be more cost-effective, and can be more sensitive to market and neighborhood conditions. True, most of the reforms I’ve proposed will not appeal to members of the Tax Credit Industrial Complex, whose members have long since figured out how to get the most benefit for themselves out of the program as it currently stands. But should their self-preservation drive our nation’s affordable housing policies?

The views expressed in this article are the author’s, not those of the Center for Community Progress.

Very thoughtful article.

Several other things that need to be explored:

1. Small properties unable to access LIHTC. At least in high cost cities it is generally understood that investors will not invest in projects under 20-25 units. If LIHTC is to be used more for existing naturally occurring affordable housing ih need of capital investment, changing the program requirements that make small properties “infeasible” for LIHTC investment needs to be tackled

2. With most LIHTC projects underwritten at rents affordable to households with income between 45 percent and 55 percent of median income, the majority of the applicants either wind up paying an exorbitant rent or simply being disqualified. In fact many jurisdictions allow an applicant that would pay more than 40 percent of income for rent to be disqualified. . In Boston, where typically there are more than 10 times the number of applicants as available units in a new LIHTC project up to 70 percent of the initial applicants may be disqualified because they cannot afford the affordable housing. Greater integration of Section 8 Housing Choice voucher administration with LIHTC tenant selection is an absolute must.

Alan,

Thanks for your thoughts on this subject. Clearly we need more financing tools to adequately address the range of housing needs in our communities. One factor I didn’t see you mention is the impact of income to rent ratios used by owners and/or required by local/state funders on the rent burden of those who are housed. If an income to rent ratio is lower than 3:1 then the folks moving in will be by definition rent burdened unless they also receive a rent subsidy. This isn’t a problem with the LIHTC program as much as it is an issue with owners and funders who want to lower barriers and use LIHTC units to house lower-income households. I worked in one jurisdiction that limited income to rent ratios to 1.5:1. It is an easy issue to address, but the result would be a whole lot of people at the lower end of the income spectrum would no longer be eligible for LIHTC housing. To address this issue we need more direct rent subsidies to low AMI households and/or deeper subsidies to housing project developments, but I don’t see either of those options in our immediate future.

I disagree with your premise “that the LIHTC program is – and should be – a program that serves households at 30% AMI…” The program’s inception and its continued support is based in very large part on the intent that the program serve the children of middleclass families as these children move out of their parent’s homes and start their adult working lives and their own family formations. It has stretched, over the years, to serve ever deeper income targeting through the cumbersome cobbling together of additional resources, which is frustrating for at least two reasons – (1) far too much time and money is expended to cobble together these resources and (2) the primary resource for serving 40-60% AMI households is diluted as it is diverted to serving the very poorest of our society. I propose that the solution is not to further enable the existing LIHTC to serve 30% AMI and below but, rather, to create a separate and distinct program to serve these households, freeing the existing LIHTC programs to serve their original purpose. I propose that this separate and distinct program be either (a) a HUD 811/202 format that allows for a one-stop 100% HUD funded project owned and operated by mission purpose non-profits or (b) a 12% LIHTC program that provides sufficient equity to eliminate perm loans and minimize the coordination of so many different federal, state and local funding programs.

With respect to using tax credit proceeds to create grant funds for rehab of existing properties, that mechanism would result in exclusion of for-profit property owners as the grant would result in a taxable event that would cause a third of the funds to be lost to taxes. Again, if a separate 12% LIHTC program funded very-low-income targeted projects then more of the existing 4% and 9% LIHTC could be allocated to rehab work through the normal credit process.

Many seem to be very critical of the LIHTC program and the LIHTC industrial complex but, having been involved when the program was in its infancy and credits were garnering just $0.48/credit dollar (and projects were required to perform with much greater debt service margins) I see that the LIHTC industrial complex has many benefits including lobbying power to preserve and expand the program and attracting creative financial structuring to squeeze much more juice out of this precious fruit.