This article is part of the Under the Lens series

New AFFH Rules: What You Need to Know

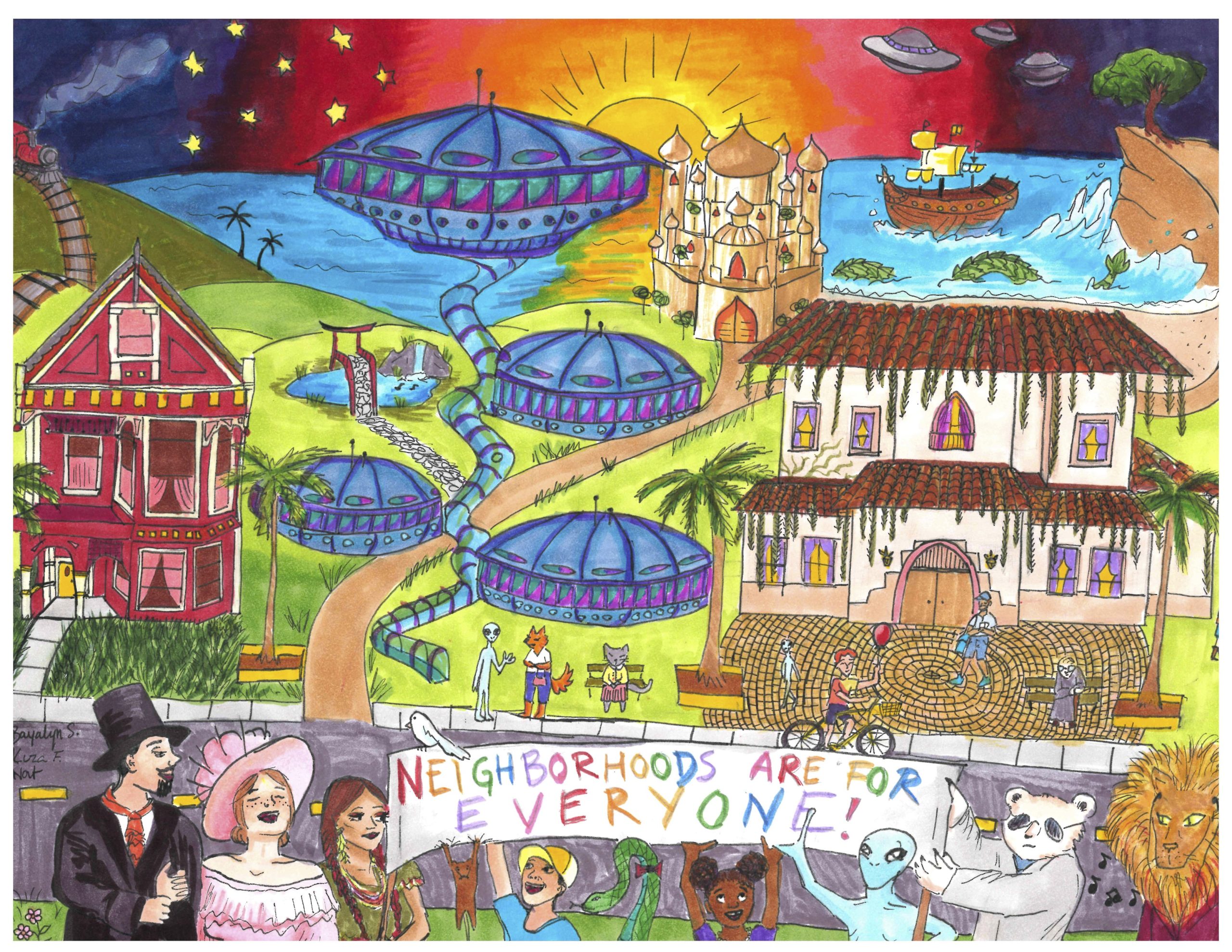

A fair housing protest in the Lake City neighborhood of Seattle, in 1964. Photo from the Seattle Municipal Archives, via Flickr, CC BY-2.0

The Biden administration in January announced a much anticipated and controversial proposal that would require many cities, counties, and states to reduce segregation and eliminate discriminatory housing policies within their borders.

The proposed new Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing rule would reinstate a requirement that jurisdictions receiving HUD funding show what they’re doing to address inequitable patterns of housing and other resources.

Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing, or AFFH, was first established as a mandate for federal agencies by the Fair Housing Act of 1968. It requires that HUD and its grantees not only avoid discriminatory practices, but go further and “proactively take meaningful actions to overcome patterns of segregation, promote fair housing choice, eliminate disparities in opportunities, and foster inclusive communities free from discrimination.”

‘We actually expect this rule to result in meaningful actions being undertaken all across the country.’

HUD adopted its first AFFH rule with a planning requirement for grantees in 1995, and it issued a more rigorous version in 2015. That regulation was effectively dismantled in 2018 by then-President Donald Trump. In a comment widely described as a racist appeal to white voters, Trump promised suburbanites “you will no longer be bothered or financially hurt by having low-income housing built in your neighborhood.”

For HUD officials and fair housing advocates, the new rule represents an opportunity not only to revive AFFH but also to put some teeth into a legal concept and an obligation that have never been fully implemented.

“We actually expect this rule to result in meaningful actions being undertaken all across the country, to finally fulfill the promise of Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing that was established in 1968,” said Demetria McCain, HUD’s principal deputy assistant secretary for fair housing and equal opportunity, during a press conference in January.

The success of the rule will depend in part on the capacity of the perennially understaffed and arguably underfunded HUD to manage a flood of fair housing plan submissions. Thousands of jurisdictions will be required to submit Equity Plans every five years for review and revision, as well as annual updates describing their progress. The proposal is an administrative regulation and does not bring any new funding for implementation.

But the enforcement effort would be aided by a new public complaint process, which would offer a simple way for anybody to alert HUD of AFFH violations the agency should investigate. Those could include zoning rules that prevent construction of affordable multifamily apartment buildings in suburban neighborhoods with good schools and transit access, or a pattern of siting polluting industries in communities of color, for example.

The rule also aims to streamline the cumbersome planning process and strengthen jurisdictions’ community engagement requirements, among other changes.

“We’ve got finally, hopefully, a framework that will, at least within the context of HUD programs, point us in the right direction. And not just point us, but actually get us moving,” says Debby Goldberg, vice president of housing policy and special projects at the National Fair Housing Alliance (NFHA). “It’s not an instant solution, but I do think it’s a shift in direction and an increase in momentum that are just critical and just really, really needed.”

A Wavering Commitment

HUD’s enthusiasm for AFFH was fitful from the start. After the Fair Housing Act became law, HUD Secretary George Romney tried to use its AFFH language to reduce segregation in an initiative called “Open Communities,” which withheld water, sewer, and highway grants from white communities with discriminatory zoning policies and pressured them to build affordable housing. He won concessions from a few cities, but some northern suburbs and Southern congressmen complained to President Nixon, who shut the program down.

HUD Secretary George Romney stands with Richard Nixon in Detroit. Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Archives

In the years that followed, HUD and other agencies AFFH covers, such as the Department of Transportation, largely resisted or ignored the law. In her history of AFFH for ProPublica, Nikole Hannah-Jones reported that HUD didn’t withhold a block grant from a single non-compliant community between 1974 and 1983, and only did so twice between 1983 and 1988. “HUD has sent grants to communities even after they’ve been found by courts to have promoted segregated housing or been sued by the U.S. Department of Justice,” she wrote.

Yet federal courts and legislators repeatedly upheld AFFH. In a 1970 case in Philadelphia, a judge ruled that HUD was required to assess racial impact when it approved a redevelopment project, and in a 1973 case the New York City Housing Authority was ordered to aim for integration when admitting tenants to public housing. In 1974 Congress created the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) program and reaffirmed that grantees had to certify they would affirmatively further fair housing as a condition of receiving funds. It passed additional laws affirming AFFH in 1990 and 1998.

In 1995, under President Bill Clinton and HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros, the agency adopted its first AFFH regulation. It required recipients of CDBG, HOME, ESG, and HOPWA funding to conduct an “analysis of impediments,” or AI, which would identify negative factors—like restrictive zoning codes, poor quality schools, and unfavorable lending terms for people of color—and to take steps to overcome those obstacles to equity and desegregation.

In a landmark 2006 case, the New York-based Anti-Discrimination Center (ADC) sued Westchester County under the False Claims Act, alleging the county had falsely certified it was meeting its AFFH obligations in order to receive $52 million from HUD over 6 years. A federal judge ruled for ADC and in 2009 Westchester entered into a consent decree. The county agreed to a $62.5 million settlement that included spending $52 million to develop 750 units of affordable housing in areas with small Black and Latinx populations. Westchester also banned source-of-income discrimination by landlords.

But critics say the case’s outcome illustrates the limits of the federal government’s willingness to meaningfully further fair housing. When the county refused to act to end exclusionary zoning in its wealthy white suburbs, HUD declined to pursue sanctions for that recalcitrance.

“The units themselves were not the transformative element. What was supposed to be transformative was using the units to bust down barriers and obliging Westchester, first, to acknowledge its authority to do so, and then to take legal action against those of its towns and villages that retained barriers,” says ADC Executive Director Craig Gurian.

Instead, towns were allowed to cram a limited number of affordable housing projects in “a variety of absurd places,” Gurian says. The housing lacked market-rate units to provide cross-subsidies, making it costly and difficult to build. Despite Westchester’s failure to fulfill many of the terms of the consent decree and over Gurian’s objections, a federal monitor ended the long-running case in 2021.

Advocates Step Up

Despite HUD’s spotty enforcement, fair housing organizations continued using the courts to force policy changes. In 2006 advocates sued St. Bernard Parish in Louisiana over discriminatory zoning ordinances it enacted after Hurricane Katrina. After years of litigation, HUD threatened to cut off the community’s grant funding, the ordinances were repealed, and the parish settled a Department of Justice lawsuit.

In 2008 NFHA and other groups sued HUD and Louisiana over a federal home-rebuilding program that discriminated against Black homeowners, winning hundreds of millions of dollars of additional grant funding for affected households.

Advocacy groups have also used a HUD administrative complaint process to get the agency to enforce AFFH. In response to a complaint filed in 2009, HUD threatened to withhold up to $1.7 billion from the state of Texas until it agreed to update its AI and reallocate Hurricane Ike disaster relief funding to assist low- and moderate-income households. Galveston also agreed to rebuild damaged low-income housing, something it had previously resisted.

On a few occasions housing activists have sought to use AFFH’s broad scope to force policy changes only indirectly related to housing. For example in 2017, the nonprofit Texas Housers organization filed a complaint with HUD about Houston’s discriminatory storm drain system. The group highlighted the inferior infrastructure in predominantly Black and Latinx neighborhoods, including open ditches that fail to protect homes from storm flooding. Last year HUD found that Texas’s distribution of federal disaster funding for flood-prevention measures discriminated against communities of color, but the agency has not withheld any monies.

Momentum to reform HUD’s approach to AFFH planning began building after the 2009 Westchester decision and the publication in 2010 of a General Accounting Office report on the Analysis of Impediments. The report described HUD’s shoddy implementation of the 1995 AFFH rule, finding that many AIs were out of date and that the agency did not require grantees to update the analyses or even submit them to the agency for review.

“Some jurisdictions actually tried to fly under the radar, never doing anything,” says Thomas Silverstein, associate director of the Fair Housing & Community Development Project at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “Some jurisdictions claimed that their Analysis of Impediments was embodied in the text of a single email, or it was just a couple pages long … . Most jurisdictions did something at some point, but there’s a tremendous inconsistency in the depth, quality, and frequency of what was done.”

The Obama administration’s HUD Secretary Julián Castro issued a new AFFH rule in 2015. It included a revised planning requirement, called an Assessment of Fair Housing, that used a data-driven analysis of local conditions, and it established a submission schedule and a requirement that HUD review the assessments. The rule also added public housing authorities to the list of covered entities.

The rejuvenated planning process helped spur policy changes in a few big cities, according to a summary by the national research organization PolicyLink. In Philadelphia, the Assessment of Fair Housing goals included increased legal representation for low-income tenants in landlord-tenant court, and the city council later launched a program to guarantee representation for tenants facing eviction in certain ZIP codes. In Boston, the process led the city to require developers to analyze displacement risk and integrate mitigation measures when planning their projects.

In Chicago, after a complaint by environmental justice organizations, HUD found a pattern of polluting facilities being shifted from white neighborhoods to Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. The agency required the city to adopt an enhanced fair housing planning process that includes planning for overcoming disparities in environmental impacts. Last year Chicago denied a permit to the metal-shredding operation whose relocation plan had spurred the original complaint.

But the new AFFH rule did not last long. Before it could be fully implemented, and with only 49 assessments submitted, Trump and HUD Secretary Ben Carson rescinded it. HUD told jurisdictions to revert to the ineffective 1995 AFFH rule, stopped accepting housing plans, and put out another rule, Preserving Community and Neighborhood Choice, with a nearly meaningless AFFH obligation.

After President Biden took office in 2021, HUD adopted an interim regulation that restored much of the 2015 process and began crafting a new final rule.

An Improvement, With Caveats

The current proposal’s main advantage may be its arrival in Biden’s first term. Assuming the president wins a second term, HUD will have some time to implement the rule widely and refine it before a successor administration that may be opposed to AFFH takes office and tries again to curtail the fair housing planning mandate.

The new rule also appears to address some problems that surfaced during the short life of the 2015 regulation, Goldberg and others say. They say the new Equity Plan format is not duplicative like the Assessment of Fair Housing, which required jurisdictions to enter the same information over and over, and it’s clearer on how they are to use data findings to set goals.

‘It will need years of implementation and rollout for all those mechanisms to work, and it will need to not be something that just changes with each presidential administration.’

Cities and other entities subject to the rule will have to report on their progress every year as a way to keep them accountable to those goals. HUD plans to post all the Equity Plans and response comments online; NFHA wants the agency to require jurisdictions to post the plans on their own websites as well. The new rule envisions a progressive disciplinary process, in which HUD uses the threat of a loss of CDBG funds to get jurisdictions to achieve their fair-housing goals before it cuts off grants.

“It will need years of implementation and rollout for all those mechanisms to work, and it will need to not be something that just changes with each presidential administration,” Silverstein says.

But the proposal also retains basic aspects of HUD’s previous AFFH rules that have been criticized, such as the flexibility of the goal-setting process. Goldberg and others defend that approach, saying it allows communities to develop very different types of plans depending on their needs and to incorporate community engagement. But Craig Gurian of ADC criticizes HUD for making a point of not dictating the exact steps jurisdictions must take.

“Any real HUD review process would need to take an independent review of what is actually needed to make change,” he says. Gurian argues that HUD should be ready to impose remedies, and to not only cut off funding but also impose additional penalties on recalcitrant jurisdictions like Westchester County. He also predicts battles over Equity Plan certification as jurisdictions try to use terms like “balanced approach,” “equity,” and “anti-gentrification” to whitewash policies that preserve segregation.

At the same time, Gurian praises the new public complaint process and the proposed rule’s straightforward acknowledgment that the nation remains highly segregated by race. Another positive is that it offers communities options to invest in community assets and preserve existing housing, as opposed to building a project that “simply perpetuates patterns of concentration” of low-income housing, he says.

“The rule is clear that there are actions being looked for that will create material change, and that where you can create greater fair housing choice outside of segregated, low-income areas, you must do so,” he says. “The proposed AFFH rule is a serious effort that clearly represents an upgrade over what has come before.”

Editor’s note: As of April 6, the comment period for the proposed rule has been extended. Comments should be received on or before April 24.

|

|

Some errors in this essay. For example, AFFH is a HUD rule and never covered and doesn’t cover USDOT.