A patron visits the Jack Hadley Black History Museum in Thomasville, Georgia. The museum is located in a neighborhood that was part of a decade-plus long revitalization project. While the project has earned a slew of awards, folks who would have traditionally lived in the area can no longer afford housing there. A new community development corporation is hoping to change that. Photo by flickr user Judy Baxter

Thomasville, Georgia, has a population of about 18,500 and sits about 10 miles from the Florida border. Like many small towns, its inner core—a four-block area known as “The Bottom”—had been disinvested for decades. In the early 20th century, the area served as the heart of the town’s Black community, and many of the businesses and homes in the neighborhood were owned by Black families. But by 2008, most of the businesses had closed, and only six homes were owner-occupied. The rest were either “dilapidated flop houses or exploitative rental properties,” says Alston Watt, director of the Williams Family Foundation of Georgia, a private grant-making nonprofit based in Thomasville.

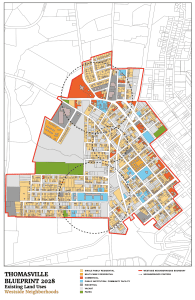

The dotted circles are neighborhoods that will be targeted for investment. Illustration courtesy of the City of Thomasville

Just before the mortgage crisis in 2008, the foundation provided seed money to the city of Thomasville to help fix the half-dozen owner-occupied homes and buy the other run-down properties. The city formed a historic preservation group, which determined which houses were salvageable, where to add open space, and how to fix up the neighborhood. The project took 12 years to complete—the economic downturn delayed its progress—but by 2020, the West Jackson Streetscape Project was winning a slew of historic preservation awards. The goal of the project from the beginning, according to Watt, was to create a neighborhood with one-third low-income housing, one-third middle-income housing, and one-third market-rate housing. What materialized in a neighborhood that was for years home to mostly low-income residents was a revitalization project that included a Black history museum, an amphitheater, green infrastructure, and a “net gain of 30 new businesses” paid for with $8 million in both public and private money.

“It was, like many of these projects, quickly gentrified,” she says. “The entire neighborhood has been improved and no one has been pushed out of the neighborhood, so it hasn’t been gentrified in that respect, but people who would have traditionally lived in that neighborhood are no longer able to access it.”

[RELATED ARTICLE: What Does ‘Gentrification’ Really Mean?]

Several community members took issue with the city’s role as a developer, Watt says, and they also wanted to find a way to create and retain housing priced for lower-income residents. So in 2020, Watt and other local partners decided to form a community development corporation (CDC). The city of Thomasville budgeted $50,000 a year to fund a startup CDC and allocated federal stimulus money to the project. The Williams Family Foundation provided funding to hire a consultant to set up the new CDC’s initial board, define its legal structure, and identify neighborhoods where they’d focus initial development work. Since getting the idea off the ground, the board and the consultant have been working with people from dozens of existing CDCs across the country.

“Anyone who’s willing to talk to us, and they all are,” Watt says. “That’s the beautiful thing about this ecosystem … people are really energized about the CDC model. I feel very convicted that even though we’re plowing a little new ground here—because rural CDCs haven’t really been tested yet—I feel like they’re so successful in other places, if they’re going to be successful [in rural areas], we can be a beta test for that.”

CDCs on the Rise

As it turns out, the folks in rural Georgia who are accessing the CDC model to bring about change in their community are part of a groundswell of new CDC formation. Frank Woodruff, executive director of the National Alliance of Community Economic Development Associations (NACEDA), says that in the last two years he’s received more inquiries from individuals and groups exploring the idea of starting a CDC than he got in the decade-plus after joining NACEDA. And while CDCs traditionally exist in more urban areas and focus on either creating new housing or rehabbing disinvested neighborhoods and housing, Woodruff says he’s been surprised by the number of inquiries he’s received from people in suburban or rural areas who are interested in learning how a CDC could help their community. And not all those inquiries have been housing related.

“So the question is, in the last two years, is what we’re seeing with these people who want these new kinds of groups or CDCs, is this an indicator of future trends?” Woodruff says. “What they have in common is they all want to have some sort of institution in which they can put money and make changes to the place they live. There’s some sort of communal sense of wanting to change their place.”

It’s also worth asking why nonprofit CDCs, rather than city or county governments, should take on projects like building and rehabilitating low-income housing or tackling neighborhood improvement projects. While each area has its own unique issues and features, sources for this story consistently said local governments lacked the staff, funding, and flexibility needed to address problems quickly and effectively. In Thomasville, for example, Watt says efforts to get nonprofit developers interested in infill projects “weren’t getting any traction.” (These are projects sited on vacant or under-utilized parcels within already-developed urban areas.)

“I realized this was because it was being led by the city, and they don’t have the vision or the capacity, quite honestly. We have really strong city leadership, and we have a great planning department, but they’re also focused on so many other things,” she says. “So they were just playing whack-a-mole trying to fix things … We were continuing to look toward the city to take the lead and they just couldn’t do it.”

CDCs’ Urban Roots

CDCs started as a grassroots, bottom-up response to the government’s top-down, racist, and often community-shattering “urban revitalization” programs of the 1940s and ’50s, which decimated city neighborhoods that were often where a metro area’s Black and brown people lived. In 1967, Sen. Robert F. Kennedy and Daniel Patrick Moynihan helped create the nation’s first CDC—the U.S. Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation. Its purpose, Moynihan said at the time, was to “get the market to do what the [government] bureaucracy cannot.”

That’s exactly what CDCs began doing—and still do. Civil rights organizers and activists in the late ’60s began forming their own CDCs to support and rebuild disinvested urban neighborhoods. Their presence increased communities’ economic and cultural strength—at times creating a chain reaction that increased property values by as much as 69 percent compared to what they would have been without CDC investment.

[RELATED ARTICLE: The Past, Present, and Future of Community Development]

Through philanthropic investment, nonprofit support, and government funding, communities that had historically been denied updates to infrastructure, access to capital, employment opportunities, job training, and adequate affordable housing options were able to lift their residents out of poverty, build and maintain schools, and create decentralized systems of neighborhood support. Today, there are at least 5,700 CDCs (also known as community-based development organizations, or CBDOs) operating in the U.S., reporting $27.7 billion in annual revenues to the IRS, according to a recent report by the Urban Institute.

CDCs are most often located in cities hurting from loss of manufacturing jobs, outmigration, disinvestment, and urban renewal, and typically focus their efforts on developing, rehabilitating, and maintaining affordable housing, though they’re also used as vehicles to invest in commercial properties, start community development financial institutions (CDFIs), and operate businesses.

CDCs’ Rural Shift

But since the pandemic began, folks like Woodruff who’ve been involved in creating and supporting CDCs for years say they’ve seen increasing interest in starting CDCs in more and more suburban and rural areas. In California, for example, Roberto Barragan, who started his tenure as executive director of the California Community Economic Development Association (CCEDA) three years ago, has fielded recent inquiries from towns like Crescent City—the only incorporated city in Northern California’s Del Norte County, which has a population of around 6,700—and San Luis Obispo, which has about 47,000 residents. Both towns have had high poverty rates for decades. Barragan has also received calls from larger cities, such as Modesto, Fresno, Stockton, Sacramento, and Bakersfield, indicating a marked increase in overall CDC interest across the state.

“There hasn’t been this kind of CDC momentum until just recently … I get at least a call a week from an organization looking to do something,” Barragan says. “During the pandemic, they were called upon to provide resources, establish food banks and pantries, and provide services to their populations. Coming out of the pandemic, they’re like, we’ve done this work, how do we formalize it and create some infrastructure around it? How do we seek funding to support it?”

CCEDA has also received more inquiries from faith-based organizations looking to start CDCs, particularly from the Black, Latino, and Korean communities. Barragan says that with this uptick in interest, he’s noticed a shift away from larger entities identifying disinvested communities and bringing in outside resources and leaders to create CDCs. Many of the recent inquiries Barragan’s office has received have come from locals looking to improve their own communities, with leadership that reflects the community makeup. While this may be true in some places, most people Shelterforce spoke with who are looking to start CDCs are still in some way involved in local government and/or existing philanthropic organizations. But, at least in Barragan’s service area, folks seem to be taking a grassroots approach to CDC startups.

“The conversation right now is people really trying to achieve equity,” he says. “And that has to begin with the leadership being reflective of their communities. People really want that model of equity in the organizations that serve them.”

It appears that people interested in starting CDCs aren’t just shifting their focus from urban to rural areas, in some instances they’re also shifting their scope away from housing-related efforts. For instance, in rural Loudoun County, Virginia, Al Van Huyck is trying to gain local support for a CDC that would focus on supporting farmers so they’re not tempted to sell their land. Van Huyck says traditional farms and existing land uses are being pushed out as new buyers move in, buy farmland, build new homes, and cease farming operations.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Creative Ways to Finance Agriculture]

“We have a significant group of people who want to keep the area rural and who want agriculture, horticulture, and animal husbandry. The [new buyers] want paved roads and lighted ball fields and other amenities,” he says. “So I went online, looked around, and came up with CDCs as a private-public partnership option. We have a lot of wealthy people we are trying to collect funding from so that we could really help our farmers and be proactive in keeping the rural environment.”

Improving Substandard Housing

Some of the increased interest in CDCs comes from the recent influx of federal dollars cities and counties received via the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (better known as ARPA). Barragan says those dollars have factored into the activity in rural California. The same goes for one CDC in Springfield, Missouri.

The issues in Springfield started about four years ago, when the city suddenly had about 500 mostly single-family rentals facing foreclosure. A local real estate investor and owner of a property management company called 417 Rentals, Chris Gatley, owed $19 million to area banks. Gatley filed for bankruptcy, and his rental business, “just sort of imploded,” says Brian Fogle, president and CEO of the Community Foundation of the Ozarks. “Nothing was getting fixed, sewers weren’t working, things were breaking. It was turning into substandard housing.”

The bulk of the homes Gatley owned were foreclosed on, and by 2020, many had been purchased by other local investors, repaired, and sold. The city also bought several of the properties and some vacant lots, but with all those units hitting the market at the same time, Fogle says the city didn’t have the staff or resources to rehabilitate the properties it purchased. It also couldn’t keep up on inspecting the purchased properties and enforcing code violations. Looking for ideas, Fogle contacted some of his friends in city leadership positions in neighboring St. Louis, who in turn connected him with Woodruff at NACEDA.

[RELATED ARTICLE: How to Fight Vacancy? Do It All]

“Frank [Woodruff] sent us to Des Moines where there’s a great [CDC] example and model called Invest DSM that’s been up and running about three years,” Fogle says. “We loaded up a bus and we went up and spent several days with their staff touring their neighborhoods. It was very eye-opening, seeing the great work and the success they’re having. So we came back and decided this is something we need to do here.”

And they did. They’ve requested $1 million each from the city and county’s ARPA money to start a CDC modeled after the Invest DSM framework. They’ve received donations and expect some additional buy-in from local banks. With this money, Fogle and several local leaders plan to establish a nonprofit that will purchase some of the dilapidated properties from the city, redevelop them, and sell them. The new CDC will focus its purchasing power on single-family homes with the intent of rehabilitating and selling them to owner-occupants. They hope to be operational this autumn.

“We feel really good about being able to get this kicked off and we’re approaching it as a three-year pilot,” Fogle says. “If it works and we do what we think we can do, we’re going to go back and ask for ongoing funding because it’s going to benefit the community, it’ll benefit property taxes, it’ll mean less dangerous buildings and properties and headaches [for the city].”

The Model for Springfield

It certainly helps that Springfield has a successful example to model its new CDC on. Invest DSM was born in 2019 out of a yearlong study conducted by the city of Des Moines, Iowa, that evaluated the efficacy of a decades-old neighborhood revitalization program run by the city. That program had minimal funding for “taking on a batch of neighborhoods, doing specific small-area plans for them, then just kind of putting the plans out in the world, like, we hope they get implemented,” says Amber Lynch, the current director of Invest DSM who for a decade worked as a neighborhood planner with the city of Des Moines.

“The evaluation found—as we suspected, those of us who were on staff on the ground—that the program wasn’t really getting results,” she says. “It was a great governing tool in terms of city government engaging with neighborhood stakeholders, but because it was so under resourced, it wasn’t translating to actual change.”

[RELATED ARTICLE: Revitalization: Not Despite Us, but Because of Us]

The evaluation also found that assessed values in the city center weren’t increasing at the same rate as homes in the suburbs, meaning that single-family homes in Des Moines weren’t generating enough equity to allow owners to borrow money they needed to perform routine maintenance, Lynch says, causing many houses to fall into disrepair. It also meant undervalued homes weren’t generating adequate property tax revenue for the city. The then-city manager, who came from the city’s finance department, was tasked with figuring out a way to fix the structural deficit issue.

A driveway before it was replaced via Invest DSM’s program for the Drake Special Investment District.

And the same driveway after replacement. Photos courtesy of Invest DSM

“The idea became, we need to be using neighborhood revitalization as a tool to stabilize our tax base and get our real estate back to performing in a healthy way so that owners have equity in their homes, they can keep up with deferred maintenance, and we can maintain a housing stock that attracts new people over time,” Lynch says. “That was really the compelling turning point. By the time we got to the end set of recommendations that said, you know, we need to be approaching this work very differently … everybody was pretty bought into the idea that this was a crucial problem for the city that really needed to be dealt with.”

Invest DSM became the solution. With $5 million each from the city and county, Invest DSM launched a cost-matching Block Challenge Grant Program, which requires groups of at least five neighbors who live within visible distance of one another’s front doors to apply together. When at least five neighbors apply (either owners or renters with the property owner’s permission) the CDC will match each applicant dollar-for-dollar up to $2,500 on “curb appeal-type improvement projects,” Lynch says.

“We launched in April 2020, right as the pandemic began. We thought we would do, by the end of that first summer, 50 projects—we did 240,” Lynch says. “Really it was word of mouth. It was neighbors who knew each other taking the time to go door knock and say, ‘Hey there are programs available. I’m going to do a project. Would you be interested?’”

Invest DSM also provides grants to individual homeowners for interior or exterior improvement projects, offers “financial incentives that encourage investor-developers within the Special Investment Districts to make above-market investments in properties that improve the desirability of the neighborhood,” and works with owners to rehab rental properties, among other programs—which have all become the model for the CDC launching in Springfield.

The Challenge of Finding Funding

In Dundalk, Maryland, an unincorporated community of about 68,000 located southeast of Baltimore City, retail and industrial vacancy coupled with an aging population was creating similar problems to those in Springfield and Des Moines: homeowners unable to keep up on basic maintenance were seeing their home values dip, creating a property tax deficit in Baltimore County.

Amy Menzer, a senior project manager in the Baltimore County Department of Planning who for more than a decade ran the “only functioning CDC in Baltimore County,” says the county is wrapping up its master planning process and is ready to fund the creation of a new CDC.

They’ve put a request for proposal out to hire a consultant. Ideally, they’d like to hire someone with experience with CDCs, with suburban areas, and with working closely with communities of color. The consultant will be tasked with creating a business plan for the first three years of the new CDC.

“I think the hope would be that an entity would be able to have a broad range of funding sources, and not be solely reliant on Baltimore County for its survival,” Menzer says. “The issues that they want to see addressed through a CDC require an organization that’s going to have a staff and can attract larger-scale resources.”

[RELATED ARTICLE: Why Organizations Should Invest in Home Repairs to Improve Health]

Baltimore County has committed ARPA funds (Menzer chose not to say how much) to get the CDC off the ground. Like the programs in Des Moines and Springfield, this CDC, once it’s established, will look for ways to help homeowners fund improvement projects that will increase the value of their homes and lead to increased property tax revenue for the county.

“Part of the reluctance to start up a CDC has been related to an understanding that it’s likely going to need some level of continued funding,” Menzer says. “And I think part of the reluctance in the past for the county to fund this sort of initiative is that, once you start something, nobody wants to be the one to pull the plug. It can kind of lead to this reluctance to even try to start it up.”

Keeping the Money Coming

Thanks to ARPA contributions, many cities and counties are currently flush with cash—which could explain some of the current uptick in CDC creation. But pandemic dollars won’t last forever, and most CDCs won’t become self-sustaining, at least not before their seed money runs out. (CDCs typically need ongoing support from philanthropic entities and/or local and county governments.) That’s where some proposed changes to the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) could keep the CDC-creation momentum going, according to Barragan. He argues that CDFIs shouldn’t be the only entities benefiting from mainstream banks’ CRA-qualifying investment dollars. Barragan (and others, including Woodruff) are pushing the Federal Reserve to allow banks to invest directly in CDCs; at present they are only allowed to put their CRA investments in CDFIs.

“Other community-based organizations haven’t received that same benefit,” he says. “For a lot of financial institutions, it’s easier for them to push the majority of their [CRA] contribution to support CDFIs because of the immediate credit.”

Earlier this year, the Fed’s Board of Governors announced it would consider amending CRA regulations and opened a comment period, which ended in August. As the CRA is written, mainstream financial institutions receive credit for making loans to CDFIs. In turn, the CDFIs provide loans and grants to CDCs and other community-based organizations. During the open comment period, Barragan says NACEDA, CCEDA, and “a number of other groups” proposed to the Fed that CDCs and other community-based organizations should be able to receive funds directly from the banks.

“CDCs, by virtue of what they do and how they do it, they provide sort of the same benefit as CDFIs. They create housing. They create shopping centers, industrial parks, social enterprises, they meet, comprehensively, a community’s needs,” he says. “There are some CDCs that have created CDFIs as part of their agenda, but at the end of the day it’s the CDCs that are doing the actual development. . . . They deserve the same kind of support from banks that CDFIs get.”

Barragan says banks regularly lend directly to CDCs for affordable housing projects and other real estate-related activities, but they’ve reduced their “charitable giving/granting to and investing in” CDCs that haven’t been certified by a CDFI. That’s because the banks would have to evaluate each project’s CRA eligibility, “as opposed to the automatic eligibility of a CDFI.”

CDCs need to strengthen its focus on economic policies at the local/regional level, we already have tons of groups focusing on housing. Over 3 decades I’ve accumulated valuable insights in economic policymaking impacts & outcomes, but I find too few “activists” interested in this topic. Because of this neglect, the status quo endures.

There has been a steady growth of CDCs over the past five decades. The 1980’s and 1990’s saw dramatic growth but it has continued at a slower and steady pace and picked up in the last few years because of the need for economic development in medium and smaller sized communities. I was President of NCCED when the first national survey was completed in 1988 using 1987 data. There were between 1500 to 2000 CDCs or what we called CBDO’s. Urban Institute and NACEDA are just completing the most recent survey and the initial data that there is “north” of 5000 CBDOs, so there has been significant growth over time as well as positive outcomes in affordable housing, commercial-industrial-community space, and job creation.

I want to correct a couple mistakes in the article since I have been working with Roberto Barragan of CCEDA in launching CDCs in California. The example of Del Norte County is not a CDC rather a CAA who wants to do a project. San Luis Obispo is a fairly affluent community. The proposed CDC is in Oceano which is the poorest community in San Luis Obispo County and not surprisingly over half Latino. We have done some ground work in Stockton and are now exploring Vallejo in the Northern edge of the San Francisco Bay. Vallejo is predominately a community of color. We are in very early stages in several other locations. Where we have made progress we have raised some initial funds from Community Foundations, CDBG, and some other state resources. We are excited that there is growing interest in CDCs in medium and smaller size communities due to the ability of the CDC to represent community and business interests plus the structure and flexibility of the organization.