Troy, New York. Photo by Flickr user Doug Kerr, CC BY-SA 2.0

In January, Jon Conlan was working the night shift at a homeless shelter run by Joseph’s House and Shelter when he heard the nerve-wracking sound of a trespasser darting through the unlocked front door and up a staircase to where the guests sleep. It was after the building’s 11 p.m. curfew, when no one was supposed to be entering or leaving unless they were requesting shelter. Conlan ran upstairs, but before he could reach the intruder, who was conspicuously holding a gun, the young man had announced he was looking for someone, and then left quickly. “It was very dangerous,” says Conlan. “We have people who are dealing with their own mental illness, their own anxiety [in the shelter]. Something could have gone wrong.”

To make matters worse, says Conlan, who was in his second year of employment with Joseph’s House, he hadn’t had any training on how to handle a situation like this. He hadn’t been provided with crisis management training, there wasn’t an active shooter plan, and he didn’t even know how to lock the door. It turns out that’s because it couldn’t be locked. And it still can’t. Staff have been asking for a more secure front door for years. Conlan says he tried to reach managers, but only one responded, and then only by monitoring the situation remotely through the shelter’s camera system. Then a SWAT team arrived in full combat gear; someone else had called the police department. “We have mentally ill Black boys in this shelter and this SWAT team is looking for a Black boy with a gun,” says Conlan, who could only wait and fret, fearing the situation was a powder keg.

Joseph’s House has been serving people facing homelessness in Troy, New York, since 1983. The organization provides an outreach van, emergency shelters, permanent supportive housing, prisoner re-entry programs, and health clinics for homeless people. In 2019 it took over the programs of another nonprofit in the nearby city of Albany. In 2020 it provided services to 1,889 people. And in 2022 its staff decided to unionize, citing concerns including situations like the one Conlan experienced, and frustration with trying to get management to address them.

A Beloved Institution

Joseph’s House’s founding principle is to provide non-judgmental services to end homelessness. This means there are no barriers to entry to housing—the belief is that giving people stable housing will give them the stability to make other changes in their lives, or to at least live with more dignity if they can’t. In practice this means Joseph’s House has been following Housing First and harm-reduction principles, which are now considered best practice, since before they were popular.

The organization developed a permanent supportive housing program because it found that people who had been doing really well in their shelters would then go off to transitional housing programs and end up back in the shelters, says Joseph’s House Executive Director Kevin O’Connor. Why? These transitional programs aimed to make people “housing ready,” often through a demanding series of programs and restrictive rules. (At least one prominent program in the region still requires sobriety and church attendance.) The dignity, respect, and inclusiveness that Joseph’s House is built on means a lot to both the people the organization serves and those who work and volunteer for it.

These are the values that attract young talented staff and believers to the organization. They are also why the staff decided to unionize instead of leave. “I love my job,” says Conlan. “I can’t stress that enough. I believe in what I do. I know what I do needs to be done. This service needs to exist and that’s why I want the organization to be better.”

Joseph’s House Staff Concerns

Many of the themes in Conlan’s story are familiar to other workers at Joseph’s House—challenges with staffing and training levels, and responsiveness to worker concerns. Often other staff step in to help during stressful situations—but then fear that by doing so they’ve given the idea that there is less of a problem than there is.

Natalie Lindop-Braun, who recently served as associate director of homeless services at Joseph’s House, gives an example: Every winter the organization opens an off-site overflow shelter, most recently in a nearby church. “The staff who were over there were seasonal staff with very little training, which is not their fault,” she says. But “the population of guests that we had this time around really struggled being over there with less support, and so we ended up bringing most of those folks back into [the main] shelter space, and increasing the density in the shelter area, trying to balance all the different kinds of safety. It was very hard on staff to be making those decisions every night. I heard them asking for more staff who are better trained, earlier in the season, and whose opinions and input were part of the program implementation from the get-go. . . . We’ve been doing this program for so many years and these concerns from staff have been raised repeatedly. I’ve heard them every year I’ve been there and this is my seventh year.”

Staff also say they’ve raised concerns that not enough attention has been paid to preventing overdoses among residents and guests. Several employees described a dysfunctional supply system for Narcan, a drug that can reverse opioid overdoses. They say they fear some overdoses may have occurred in some Joseph House facilities because Narcan (which they receive free from Catholic Charities) wasn’t distributed when it should have been.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Getting to the Heart of the Opioid Crisis]

Lindop-Braun recalls being in a spring 2022 meeting in which Amy LaFountain, director of supportive housing, said that they had difficulty getting a sufficient supply of Narcan for the Lansing Street Inn, one of the organization’s supportive housing residences. This meant that the supply they had was kept behind the desk, rather than accessible on the floors. Though O’Connor was present at that meeting, he told Shelterforce he didn’t remember hearing about any problems with the supply of Narcan and added that recent Narcan training courses have had very low attendance.

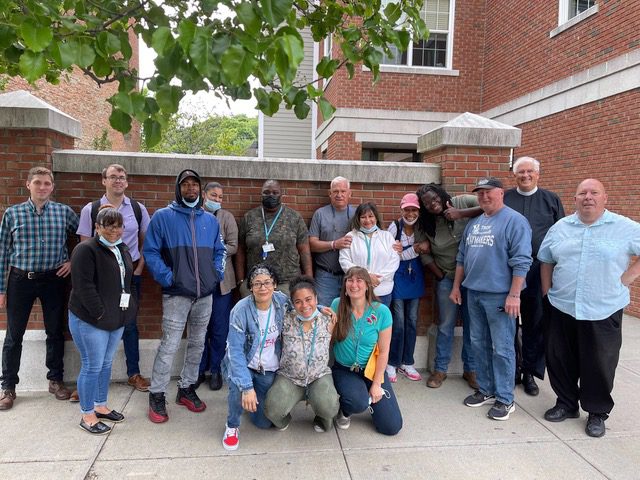

Joseph’s House workers and supporters. Sean Collins, the SEIU organizer, is second from left in the back row, and staffer Natalie Lindop-Braun is on the right end of the front row. Photo courtesy of SEIU Local 200United.

Organizing for a Voice

Frustrated with a feeling that their feedback and requests for change were not being heard, Joseph’s House workers came together earlier this year to form a union.

According to the SEIU Local 200United, about 60 percent of the organization’s 75 eligible employees signed cards indicating they would vote to unionize should an election occur. They delivered their request in May.

[RELATED ARTICLE: Putting in the Labor to Support Affordable Homes]

O’Connor issued a statement in June saying that while he wouldn’t interfere with a union vote, he would not voluntarily recognize the union. (An employer can voluntarily recognize a union if a majority of employees sign union authorization cards, skipping the need for a formal election.)

O’Connor says some employees told him they didn’t want a union and he didn’t feel he could decide for them. “It was not anti-union at all,” he says. Given the supermajority signing union cards, however, the outcome of the vote was not in doubt, and so the Joseph’s House Union Organizing Committee issued a frustrated response to this decision, writing: “We requested voluntary recognition because the situation is dire and will only get worse if our issues and concerns as frontline workers continue to be left unresolved. By forcing us to file for an election with the National Labor Relations Board, management is unnecessarily prolonging the process and perpetuating these health and safety issues.”

Ballots were distributed on July 27 and the results announced on Aug. 11. Despite the organizing challenges of a workplace whose workers are dispersed across multiple locations and programs, working many different shifts, the union prevailed by a ratio of about 2 to 1.

There is an ongoing dispute with management about exactly who qualifies to be in the union. O’Connor says that eight coordinator-level staff who organized and voted for the union, including Lindop-Braun, are supervisors and therefore cannot be in the union. (Lindop-Braun recently left Joseph’s House for a different job after this article was reported.) Their votes were held aside but were not needed for the union to win. However, whether they will be part of the bargaining unit is still to be determined. Sean Collins of SEIU Local 200United, with which the workers have affiliated, says the definition of supervisory staff involves full power to hire, fire, discipline, and set schedules, and “we do not believe these eight workers actually have that authority or discretion.” O’Connor disputes that reading, noting that the National Labor Relations Board description of supervisory duties also includes “responsibility to direct [other employees], or to adjust their grievances, or effectively to recommend such action.”

Who Has a Voice?

For several pro-union workers, O’Connor’s decision not to recognize them and draw out the process only highlighted one of the overarching issues that led them to unionization in the first place—a sense that current management is resistant to taking input from those who are on the ground. This is a common theme at other nonprofits, where workers have increasingly organized unions over the past decade.

Janet Douglass, a volunteer coordinator at Joseph’s House for over eight years, says she’s grown deeply frustrated as her suggestions and pleas have been dismissed by management. She says a “lack of transparency” between management and those working on the ground has created major systemic issues that have led to dangerous situations for staff and clients as well as a general demoralization. For example, Douglass says, she began pushing for an active-shooter policy four years ago but was dismissed. “Right now, the only thing we can do is ring a fire bell,” she says. “And everybody from that family center would come out through the front of the building. What if we had an active shooter there at the front door?”

Several staff say chronic understaffing at a supportive housing building known as Lansing Inn has sometimes resulted in unsanitary conditions in the kitchen, including a notable instance of stored rotten food discovered when workers came from other sites to provide respite staffing. Those off-site workers cleaned up the issue, but once they had done so, says Lindop-Braun, the situation was considered resolved, and the conditions leading to it were not addressed.

Lindop-Braun also says staff want to be more actively prepared to prevent overdoses, which are on the rise, especially among people recently released from incarceration, whose tolerance has been reduced putting them at extra risk. “We want to be . . . really prepared to save those lives if we need to,” she says, “and for the staff to be receiving the training, but also the emotional support, when [overdoses] happen. . . . There’s not a single social worker on staff. We definitely don’t have any trauma-informed training. The staff who’s just experienced this really intense event have to also be supporting the 20-something guests who also experienced this event. Many times the guests are helping revive folks. . . We could have an infrastructure in place. And I don’t think that that requires too much more than effort and foresight.” She notes that many staff have experience with related situations and would be eager to have the extra training to be able to step in and support their colleagues in those moments.

The contrast between facing these kinds of challenges on the front lines, and not feeling like those efforts are fully respected by director-level staff is also difficult. “Nobody [from management] visits and they stay in their little hallowed halls, and they don’t think about what other people are dealing with,” says Douglass. (The administration offices are housed on one floor of one of the supportive housing buildings.) “At one point I said something to my supervisor, one of the directors, about the shelter. She said, ‘Oh, I never go there.’”

All this weighs heavily on staffers and volunteers, who say they are suffering greatly from burnout. (O’Connor says that the staff has an 85 percent retention rate.)

Nonprofit Funding Realities

O‘Connor says he does not yet know the details of the non-compensation-related concerns that union members have to bring. He says the trainings Joseph’s House has offered recently have gotten little attendance, though he acknowledged it might be a matter of what types of training people want. On the other hand, what the HR staff has heard about when staff reached out regarding the idea of unionizing, he says, “was not about training, not about understaffing. Our HR heard from workers about compensation and benefits.” On that front, says O’Connor, he agrees with them that salaries should be higher, and says he’s been advocating ceaselessly to the state and federal agencies that run the programs for increases in those contracts. But for now, he says, the money isn’t there.

“I look forward to working with SEIU 200 to advocate together for a more sustainable funding for programs like ours, particularly in this economy, because it’s not sustainable right now,” says O’Connor. “There’s some talk about understaffing. If you can solve that problem, I’d love to join with you.”

In 2020, the organization’s expenses were $4.3 million. Of that, 68 percent came from private contributions, and 32 percent from public contracts for services—mostly state and some federal. Compensation accounted for 62 percent of the organization’s expenses.

Joseph’s House employees pose with the outreach van in an organizational promotional photo. Photo courtesy of Joseph’s House

O’Connor notes that he can’t remember the last time the federal grants the organization gets for permanent housing and street outreach have incorporated a cost-of-living increase, and the state grants have mostly stayed flat as well. When a long-sought-after 5.4 percent cost of living adjustment for human services workers went through at the state level last year, the program Joseph’s House is funded under, the NY State Supportive Housing Program, was bizarrely exempted.

Joseph House implemented raises of 6 to 8 percent for fiscal year 2022, starting in January, to get up to the current pay range of $15 to $22 an hour for the approximately 70 positions below coordinator level. According to publicly available tax filings, the nonprofit has had a negative net income every year from 2012 to 2020. O’Connor, the top paid staff member at Joseph’s House, was paid $99,000 in 2020. The median income for the region in 2019 was $73,000, and the median salary for a nonprofit executive director in the region was $86,000, according to salary.com. This encompasses nonprofits of all sizes. The top four executive staff at Interfaith Partnership for the Homeless, a shelter based in nearby Albany, New York, all made between $100,000 and $120,000 in 2019, according to 990 tax filings, as did the executive director of the shelter Bethesda House in nearby Schenectady. The national median salary for a shelter director is $105,000, according to comparably.com.

A Hope for Better Communication

Like many other nonprofit workers, even those who are clear they need a union are protective of the organization. Conlan says he’s worked other jobs, but they never felt as meaningful as the work he does at Joseph’s House. “This is the best team I’ve ever worked with. I love our team,” he says. “I’m so proud that people spoke up to try to make things better.”

The union drive appeared to bear fruit even before the vote. “Now, since we’ve said, ‘We want a union,’ suddenly we had active-shooter training,” says Douglas. “But why did we have to do that? Why did we have to say we wanted to form a union before they would fix an alarm that goes off . . . every 20 seconds, beep, beep, beep, beep, beep, and [a person who works overnight in that building] has asked for months to have . . . fixed?”

And yet, the mission and approach of Joseph’s House remains unusual enough to be worth fighting for. “Our staff are so dedicated to housing first and harm reduction and there is nowhere else for them to go,” says Douglass. “If they want to do this work because they really believe in it and they are excellent, they must do it here.”

Better communication is the hope on all sides. “Homeless services are really stretched and our staff has really needed to carry the brunt of services,” says O’Connor. “I will certainly listen. Obviously, we’re in a challenging time for hiring, particularly when it has to do with seasonal work. And ramping up and getting that staff adequately trained adequately in a short amount of time is challenging. But we would certainly work with the union representatives to address the concerns that they have.”

“The next thing is to go to the bargaining table,” says Lindop-Braun. “The exciting part really is to open up this conversation and clarify a little bit [that] . . . training and safety and respect and dignity in the workplace is the driving force [of the union].” The workers, she says, are “really looking forward to getting to tell everyone, ‘This is what we’re looking for.’”

Additional reporting by David Howard King.

Comments